Being a coach in Calgary, Alberta, my year-round training options are at the mercy of the weather. Long winters, frigid temperatures, and endless snow keep us captive indoors many months of the year. We do not have the luxury of being outside on a field or on the track to properly train speed in a year-round fashion, particularly maximum velocity. Granted, Calgary is much warmer than the place I grew up three hours further north (lovingly called Deadmonton), but the winter conditions can seriously impact the long-term speed development of many athletes.

Comparably, with the recent worldwide pandemic, many athletes are relegated to their homes and must train in basements or small spaces. This means many promising and high-level athletes are not training properly (if at all), and speed training is surely the most neglected quality.

Where space and weather are limiting factors, tools that can help develop and build speed qualities are greatly needed. Luckily, one such option exists, and it can be extremely valuable in the pursuit of speed: tethered running.

What Is Tethered Running?

I am a pirate; meaning I rarely create anything of value myself, but instead steal ideas and tools from all the great coaches out there doing great things. Tethered running—which I stole from fellow Canadian Derek Hansen, and which he started experimenting with circa 2000—is simply putting a rope or band around your hips and anchoring it to something sturdy (or held by a partner). This then allows the athlete to do a multitude of training options indoors and without much more than a few square meters.

The placement of the rope allows for a much more natural feel than simply doing the same exercise in place without the tether. The little bit of resistance provided by the rope (my personal preference is my 1-inch purple resistance band) affords the athlete the ability to lean in slightly and strike the ground in a manner more akin to upright running, creating a more realistic muscle sequencing pattern. The external resistance also means the athlete has to maintain good postural control and develop body awareness. Tethered running is also a great option when you have a bit more space and a partner handy, because they can hold the band and slowly walk forward, allowing the athlete to get more posterior chain involvement.

The little bit of resistance provided by the rope allows the athlete to lean in slightly and strike the ground in a manner more akin to upright running, says @CoachGies. Share on XIs tethered running a substitute for actual sprint training? A resounding NO! But as a tool to develop (some) speed qualities when weather and space eliminate any possibility of performing quality sprint work? Absolutely.

Think of it this way: If an athlete can’t run but still wants to train, what are they going to do? Likely weight training and bodyweight circuits training, which are fine and definitely have their place, but on their own will not develop the neurological or stiffness qualities required for sprinting. If an athlete is sitting around (like during quarantine…) then they are essentially detraining. If they are training but not doing speed-related work, they are detraining speed! This can lead to poor performances and an increased risk of soft tissue injuries once they ramp back up their training volumes (i.e., better weather or no more quarantine). Tethered running is a great adjunct to get quality speed training when the situation calls for it.

Here is an incomplete list of many of the capacities and physical qualities needed for efficient sprinting. Properly implemented tethered run training can also focus on, maintain, and even develop these areas:

- Posture

- Coordination/patterning (developing front side mechanics)

- Arm mechanics

- Rhythm, relaxation, and timing

- Frequency

- Elasticity/reactivity of the lower leg/foot

- Leg and trunk stiffness (vertical displacement of center of mass)

- Contact time

- Specific strength (hips, ankle, etc.)

- Foot/calf conditioning

- Vertical force development

Will these capacities get developed better than with sprinting? Unlikely. Will they be developed to a higher degree than if not sprinting at all? Yes!

In that effort, we’ll focus on three primary applications: speed development, extensive tempo running, and return to play.

1. Speed Development

To get fast, you need to sprint. However, tethered running is a fantastic means to work on various sprint drills, low-intensity plyometrics, and other coordination drills. If you subscribe to the “Feed the Cats” training style, these could also be great additions to the X-Factor days.

Tethered running is a fantastic means to work on various sprint drills, low-intensity plyometrics, and other coordination drills, says @CoachGies. Share on XSprint Drills

Even though a sprint drill doesn’t necessarily make someone fast, it creates context for an athlete and can develop specific postural strength, rhythm, and relaxation. When used in a tethered fashion (as opposed to in-place with no tether), the athlete can use the resistance of the band to adopt a more leaned-in body angle. This much more natural feeling position will also cause the athlete to strike the ground in a more favorable manner (under the hips) as they try to push away from the anchor point. This increases posterior chain involvement and improves foot placement.

The “Big 3” to start with are marches, skips, and runs (See Video 1 below). The sets/reps can be either repetition-based or time-based. For example, with the Tethered March you can do 2-5 sets for 10-30 seconds with 20-50 foot contacts. I’ve found multiple sets of lower repetitions for these drills work best to keep fatigue at bay and movement quality high.

Video 1. Marches, skips, and runs are a great introduction to tethered running and lay the foundation for other variations.

Other drills include (see Video 2):

- In and Out Skips

- Unilateral Skips

- Ankle/Skin/Knee Dribbles

- Booms

- Multi Boom series

- Arm Action Drills

- Power Skips

- Scissor Runs

- Snowball Runs

Video 2. In addition to these tethered running drill variations, you can try whatever your imagination comes up with!

You can also increase the intensity of each drill by altering arm position (i.e., overhead holding a dowel) or introducing some light external resistance, like a medicine ball, as the second half of Video 1 shows. This introduces novelty, movement variability/challenge, and overload without needing to design a new drill.

Low-Intensity Plyometrics

Pogo Hops, or Stiffness Jumps, are a great tool to develop elastic-reactive qualities of the lower leg, preactivation (i.e., dorsiflexion), and leg stiffness. When space is limited, adding the tether is a fantastic way to get more work out of these drills.

With the athlete now getting resistance from the tether, the recruitment strategy is different compared to simply jumping vertically on the same spot. It requires more calf involvement, and the ground reaction force will be angled slightly forward rather than straight up. Similarly, you can increase the intensity with light external resistance in front or to the side of the body (i.e., medicine ball). Repetitions would be anywhere from 8-20 seconds depending on whether you want to emphasize contact time or power or 20-45 seconds for more of a conditioning effect. Sets can range from 1-6 reps.

Great options include (see Video 3):

- 2-Foot Pogo

- 3 Mini + 1 Big (Different Amplitudes)

- Single-Leg Pogo

- Shuffles

- Mummy Shuffle

- Astride Jumps

Video 3. Tethered low-intensity plyometrics, including Pogo Hops and Shuffles.

Max Effort Drills

Obviously, the neuromuscular component of sprinting can’t be matched without actually hitting the track, and we don’t want to solely perform submax drills and jumps. We will still need to address the CNS component even if we are confined to our homes. A variety of max-effort drills can be performed with the tether. These should generally be done in short bursts (around 6-8 seconds or 3-5 reps, depending on drill) to ensure maximal outputs and high movement quality. Some of these drills take some getting used to in terms of feel and coordination, but what are you going to do…not train speed?

Drills include (see Video 4):

- Sprint Arms

- High Knees/Power Runs

- 2-Point, 3-Point, 4-Point Starts

- Kneeling Start

- Broad Jumps

- SL Jump to DL Landing

Video 4. Tethered max effort drills include arm movements and resisted jumps.

2. Extensive Tempo Running

Used by many great sprint coaches, tempo running is a fantastic tool in a coach’s toolbox. Particularly if you subscribe to the high/low model of structuring weekly training, it is a great way to get a lower intensity session to improve aerobic qualities and overall blood flow without the impact or CNS load. Increasing chronic running volumes and improving the efficiency of the aerobic engine will make the athlete more robust and able to handle higher training loads year after year, thus improving the quality of training and reducing injury risk.1,2 With limited space or limited access to quality facilities, this could be a massive component missed by athletes.

Fear not, tethered running is here to help.

Hunter Charneski wrote a great article detailing tethered tempo runs. To perform them, you run in place against the tether for a designated period of time, in an interval fashion. In terms of the sets and reps, I believe Carl Valle summarizes it nicely in this article: “The density of work has to be high enough that the body is in a constant state of deficit but not too hard that the aerobic strain can be felt at the muscular and tendon level.”

The aerobic system needs to be challenged and should be the limiting factor, not the tissues. Tempos are typically performed around 70% intensity. So, during tethered tempos, it should be a steady pace where you feel you are working, but never to the point you need to slow down due to fatigue—though you will get sweaty and your calves/hip flexors will be tired the first few times!

There are endless combinations, but I tend to defer to 25-45 seconds of work, with a 1:1-1.5 work-to-rest ratio (the athletes’ fitness levels will determine the ratios). Similar to other forms of tempo, the level of intensity is not the key, but the total volume. Thus, you should default to lengthening the duration of the run, shortening the rest periods, or increasing sets/reps rather than making the athlete move quicker. In Charneski’s article, he details approximate sets/reps to correspond with actual track distances, and session volumes for various sports and positions (refer to that article for more detail).

True, you could do this in-place without a tether, but the more natural position afforded by the band makes it much more enjoyable and easy to maintain a steady rhythm. I should note that due to the limitations of tethered running compared to running over the track or grass, I find the hip flexors get more fatigued. So, you may need to modify sets/reps/rest for particular athletes.

You could do tempo running in-place without a tether, but the more natural position afforded by the band makes it much more enjoyable, and easy to maintain a steady rhythm, says @CoachGies. Share on XIn terms of technique, I find a slightly lower knee lift, somewhere around one-third to one-half of max knee height, works well. This way you can still work on rhythm, arm action, crisp foot contacts, and relaxed shoulders. You can even perform this on a thin exercise mat for a more compliant surface to dissipate some of the forces going through the lower leg.

Another great way to extend the aerobic challenge—without adding more running—is to incorporate medicine ball exercises, flexibility circuits, or low-volume calisthenics before, during, or after the workout. This would be more than adequate as a low-intensity session for an athlete at home or in a small facility during the Canadian winter.

A great initial session I do with athletes, either on a lower intensity day or for an at-home session, is the following:

- 30” on/30” rest x 4-5 reps x 2 sets

- **1-3 minutes between sets depending on athlete fitness levels

Here is an example of a pyramid tempo workout:

- 30”+30”++

- 45”+45”++

- 60”+60”++

- 45”+45”++

- 30”+30”

- + = 30” rest

And an adapted tethered workout based off Charlie Francis’s “Big Circuit”:

- 30”+30”+30”++

- 30”+30”+45”+30”++

- 30”+45”+45”+30”++

- 30”+45”+30”+30”++

- 30”+30”+30”

- + = 30” rest

3. Return to Play (RTP)

The applications for tethered running aren’t just performance-based, as tethered running also has a very real place in rehabilitation because it increases tissue tolerance in RTP scenarios. After an acute or chronic overuse injury, part of the RTP process is to gradually reintroduce graded training stimuli to improve tissue remodeling and tolerance without exacerbating symptoms. This generally begins with low-intensity/low-volume interventions, and then gradually both of those criteria are increased based on athlete tolerance, until the athlete can handle full training.

Tethered running also has a very real place in rehabilitation because it increases tissue tolerance in return-to-play scenarios, says @CoachGies. Share on XIn the case of a sprinter or field sport athlete RTP scenario, this generally means progressing to some sort of full-effort running. Not exposing an athlete to the types of speed and external forces that they will experience in their sport during the RTP process is a surefire way to increase the likelihood of flare-ups and reinjury. Additionally, specificity is key, so for athletes who need to run, intelligently designed running progressions will provide an adequate means for progressing tissue tolerance and specific strength.

Tethered running is a great way to recondition an athlete’s lower half after an acute injury (e.g., ankle roll, hip flexor strain, pulled hamstring) or overuse injury (e.g., shin splints, plantar fasciitis), or for other injured body parts that can’t handle the load of full-effort sprints (e.g., strained erectors, rotator cuff surgery). This modality can even be useful when adequate space is available, but a modification in volume and intensity is required during the rehab process.

Let’s take an acute ankle sprain as an example. Once preliminary examinations/imaging are performed, initial therapies to restore functional ranges of motion and strength are incorporated, and the athlete is more or less able to bear weight (though full weight-bearing is not required to begin), then we can introduce tethered rehab strategies. Like any rehab situation, you will want to find an “entry point” where the athlete can perform some amount of training without substantially increasing symptoms (i.e., pain, swelling, inappropriate movement strategies, etc.). In the case of an acute ankle sprain, this entry point would likely be the standard March Drill.

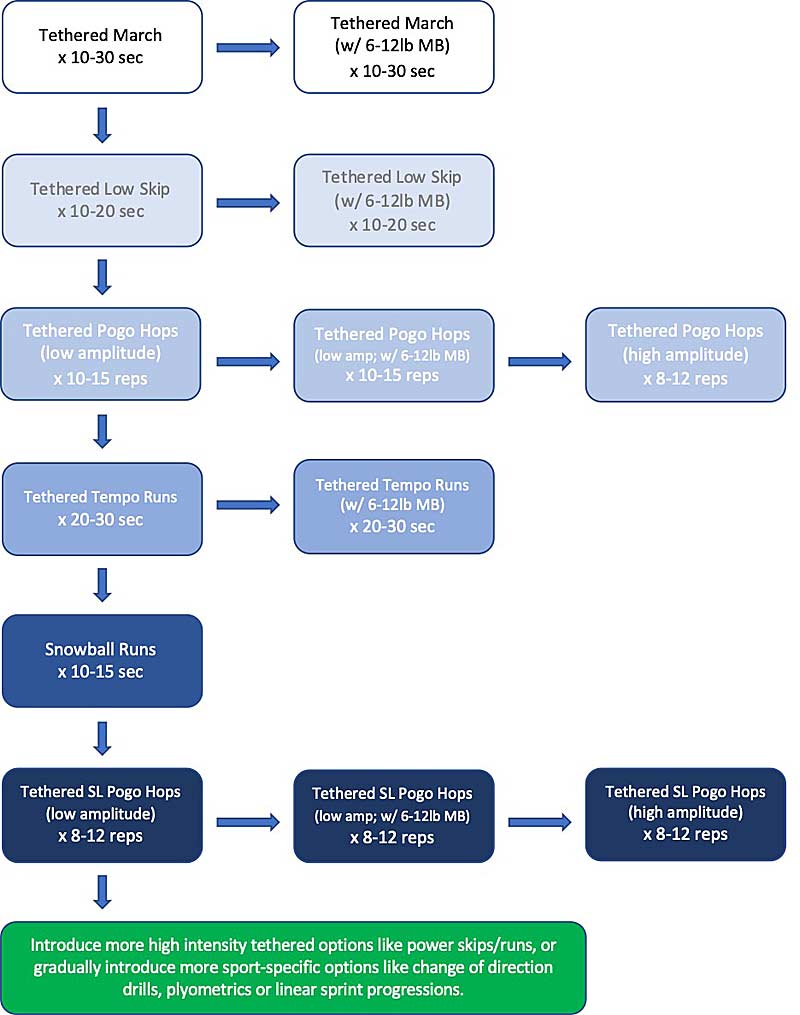

The following flowchart shows how a coach can increase the training demands over time, thus improving adaptation, by progressing the dynamic effort, external load, or volume of the drill.

Notes:

- Ensure athlete demonstrates proper dorsiflexion and pre-activation before advancing a drill.

- Sets/reps can be anywhere from 1-4+ sets depending on severity of the injury.

- Allow full recovery periods to prevent fatigue from being the limiting factor in technical execution.

- Can be partner-assisted to allow the athlete to travel forward at a slow pace.

A safe way to progress each drill is to start with what the athlete can handle. For example, use the March Drill for two sets of 10 seconds, then increase the sets to three and then to four sets of 10 seconds. If the athlete responds well, drop the sets back down to three and increase the duration to 20 seconds and progress back to four sets. When the athlete is accustomed to this workload, drop back down to three sets of 20 seconds, but introduce external resistance like a medicine ball, and similarly build up to four sets. Once this is not an issue, you would then introduce the next most dynamic drill (i.e., Low Skip), start at a low volume, and progress in a similar fashion.

Whichever route you take will depend on what the athlete can handle and how they respond, but ultimately you will want them performing the most difficult drills prior to clearing them to resume regular training (or at least reincorporate portions of regular training).

This logical progression of low intensity/low volume to high intensity/moderate volume will improve muscular strength, tendon/ligament stiffness, proprioception, and endurance qualities of the lower leg, which would surely have regressed during the initial stages of rehab. Additionally, the athlete’s tolerance to training will be somewhat reinstated, allowing them to handle higher volumes of sport-specific training sooner than if no run training had been performed. Similarly, they will have developed overall coordination, rhythm, relaxation, and fitness qualities, allowing for a more global training effect—rather than simply focusing on the ankle—and leading to a more optimal RTP scenario.

Not a Replacement, but a Good Addition

In terms of true speed development, if the training modality isn’t flat-out linear sprinting, then there will obviously be limitations and drawbacks. Though tethered running has many benefits, especially for our confined athletes, it is not a replacement. It will not replicate the ground reaction forces or vertical force development seen in upright running. It will not produce as much tension or load through the posterior chain, particularly the hamstrings. It will not reproduce identical motor patterns (i.e., foot strike, heel recovery), flight times, or stride lengths. It will also not replicate the neural drive seen at higher speeds.

Though tethered running has many benefits, especially for confined athletes, it is not a replacement for flat-out linear sprinting. But it’s a good adjunct to proper sprint training, says @CoachGies. Share on XHowever, this should not discourage its use as an adjunct to proper sprint training, especially if the other option is to do no form of sprint training at all.

Moving Onward

My hope with this article was, first, to inspire coaches in similar situations as myself, who may not have adequate facilities to sprint year-round or who are relegated to coaching in small spaces for many months due to poor weather. Secondly, my goal was to shine a light on the many useful applications tethered running can have, especially because it is a low-cost and easily accessible form of training. It can be a useful means to develop (or at least maintain) several speed qualities through specific sprint drills and low-intensity plyometrics, and aerobic qualities through tempo running, and it can be a valuable training tool in RTP protocols.

Now grab a band and get moving!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Malone S., Roe M., Doran D.A., Gabbett T.J., and Collins K.D. “Protection Against Spikes in Workload with Aerobic Fitness and Playing Experience: The Role of the Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio on Injury Risk in Elite Gaelic Football.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2017;12(3):393–401.

Malone S., Owen A., Mendes B., Hughes B., Collins K., and Gabbett T.J. “High-Speed Running and Sprinting as an Injury Risk Factor in Soccer: Can Well-Developed Physical Qualities Reduce the Risk?” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2018;21(3):257–262.