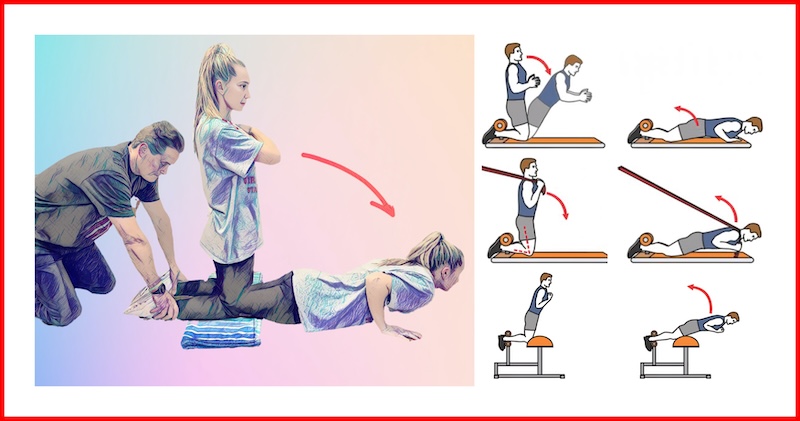

Like most Europeans, Artur Pacek started playing soccer about the time he could walk. His athletic journey took a different path in elementary school when he fell in love with basketball. Pacek continued shooting hoops through college, and he extended his passion for sports by becoming a strength coach.

Today, Pacek is the head strength and conditioning coach for BM Stal Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland’s best elite-level basketball team. He has also trained athletes from Australia, Czechoslovakia, Lithuania, Serbia, Sweden, Turkey, and Ukraine.

Pacek holds a graduate degree in physical education from the Academy for Physical Education in Gorzów, Wielkopolski. In 2011, he continued his education by accepting a six-month internship with Tim Grover at the ATTACK Athletics Center in Chicago, Illinois. Grover was the personal trainer of NBA legends Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, and Dwyane Wade. Pacek hopes to work in the NBA eventually.

Freelap USA: What are the major differences between basketball played in Europe and the U.S., and what is your general approach to training these athletes?

Artur Pacek: The pace of the game in the U.S. is faster and more intense. In Europe, teams play fewer games per week. The average number of games per week in the NBA is 3.3. The average in the EuroLeague is 2.4, and in Poland, 1.6.

U.S. players are more athletic than most European players, but many of our players, such as Luka Dončić and Nikola Jokić, are technically well-trained. These skills give them a competitive advantage.

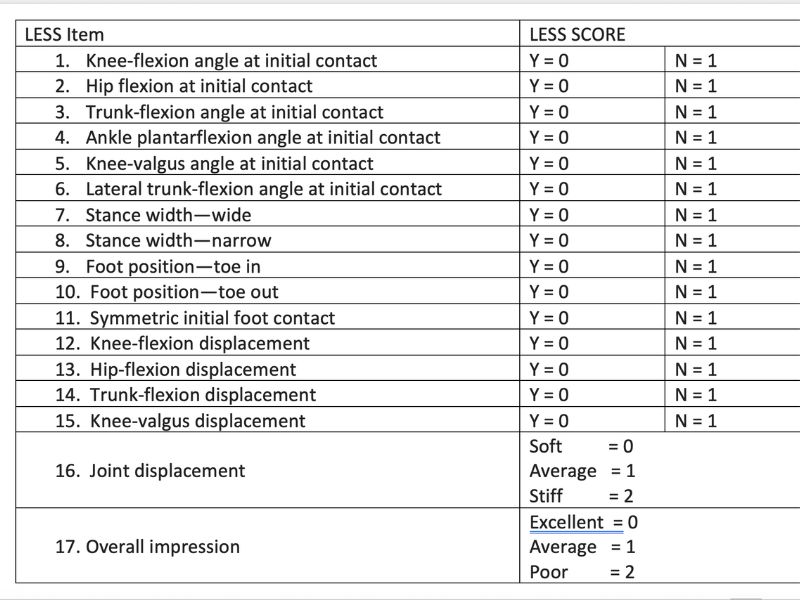

Basketball is a game of specific joint angles that cause the development and underdevelopment of individual muscle groups. These structural imbalances lead to overload and injuries. Therefore, my main task with these athletes is to maintain their strength, muscle mass, and structural balance to keep them performing at a high level.

A strength coach needs the biggest training toolbox possible and must use the right training method at the right place, at the right time, and with the right person. It’s all about adaptation and progressive overloading of the body so that we can use many tools. My approach with a new tool is to learn it, try it on myself, consult with other trainers, and only then will I add it to my toolbox. If I don’t study an exercise or training method in detail or understand it, I don’t use it.

Basketball workouts are often long and monotonous but rarely at a high intensity, so I try to provide the body with high-quality stimuli. As Coach Bob Alejo says, “Never sacrifice intensity!”

Freelap USA: How do you approach periodization?

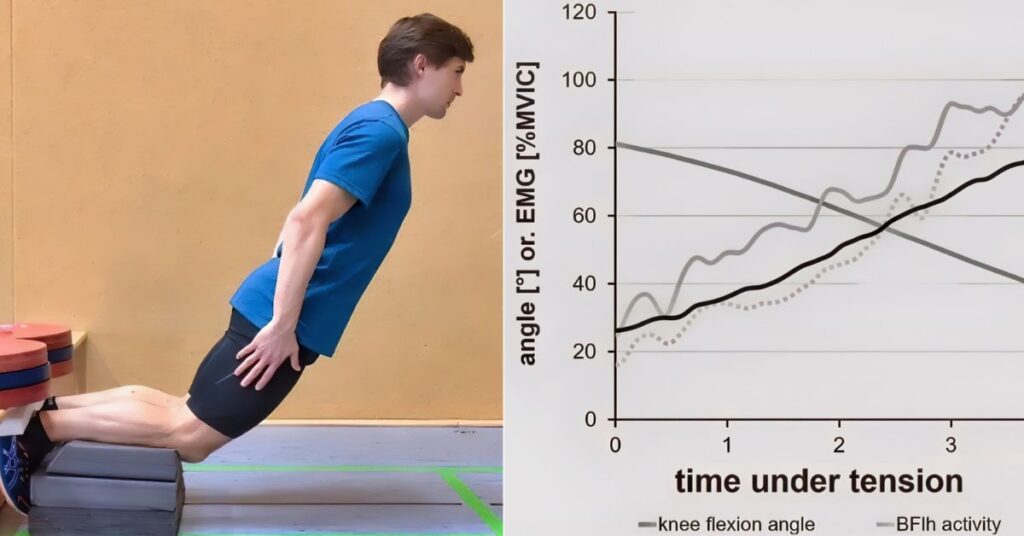

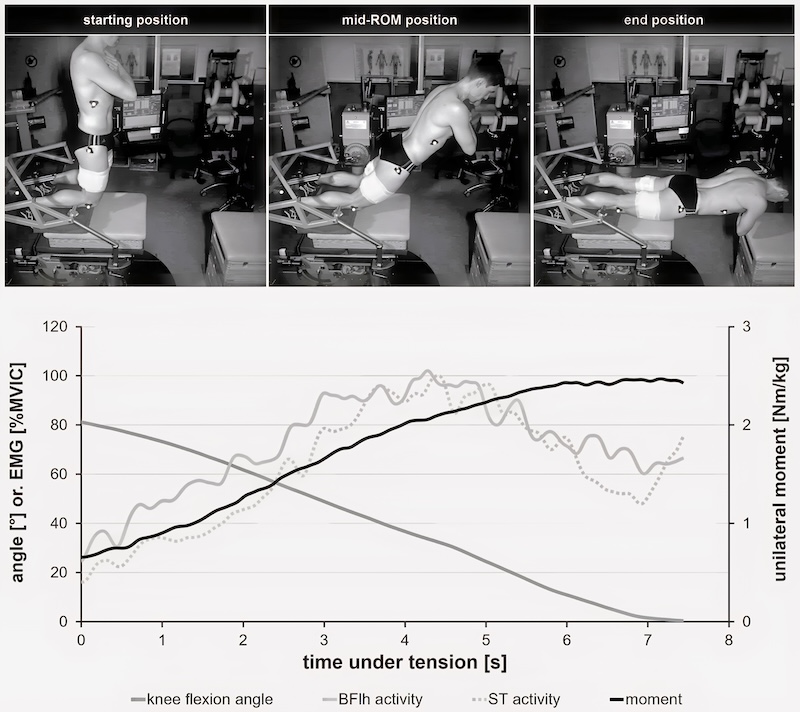

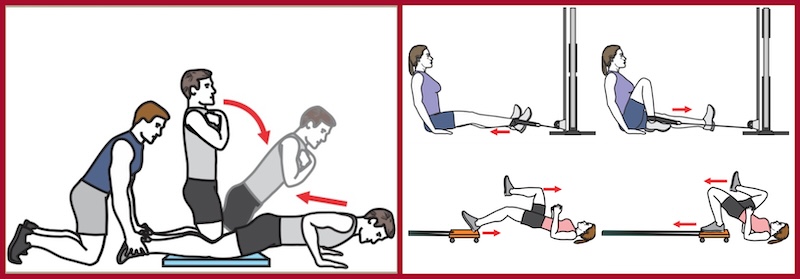

Artur Pacek: The periodization model I use depends on how long the period lasts and who I’m working with. These models include linear, undulating, conjugate using the classic strength training model, and the quad-current programming using three types of muscle contractions that Ben Prentiss promotes. I believe 80% of basketball players are undertrained in eccentric and isometric muscle contractions, negatively affecting acceleration, deceleration, and direction changes during a game.

I believe 80% of basketball players are undertrained in eccentric and isometric muscle contractions, negatively affecting acceleration, deceleration, and direction changes during a game. Share on XI divide the off-season into general and special physical preparation phases, alternately focusing on volume and intensity.

When training for volume, I emphasize the following:

- Longer range of motion exercises (tension in stretched/deep positions).

- Low impact on joints.

- Low complexity.

- Strengthen weak areas.

When training for intensity, my focus changes as follows:

- Shortened range of motion.

- Higher impact of joints/tissue acceptable.

- More complexity.

- Externally stabilized loads.

- Advantageous positions based on body type.

- Utilize the stretch reflex.

Freelap USA: What is your annual approach to training?

Artur Pacek: I divide the annual plan into four main blocks: post-season, off-season, pre-season, and in-season.

The post-season is a reconditioning phase that focuses on tissue re-education. It is not a performance model but a preparation phase to prepare the tissues for more advanced training methods.

After 8–9 months of playing basketball, the focus should be on improving weak links to restore homeostasis, muscle balance, and fascial lines. During this phase, I use yielding isometric elements in extended and shortened positions. I also like using extended eccentric contractions during this phase.

As a strength and conditioning coach, the off-season is especially important. The strength training frequency is higher than the in-season, so the body has more time to adapt, and it allows me to use more demanding methods to send a stronger signal to the body.

The pre-season is the most intense training period. Frequency, volume, and intensity are at very high levels. It is a transition phase where we try to convert what we have developed in previous periods. Due to the mix of a very large number of basketball practices and strength training workouts, my approach is individualized.

The in-season is the longest block in the annual cycle, lasting 8–9 months. In the NBA, most coaches focus on maintaining their results from the off-season and pre-season phases. Many of them use the quadrant system, popularized by Daniel Bove. My approach is individualized and influenced by how they look and their playing time, but we strength train at least twice a week. My goal is not to decrease a strength level by more than 10%–15% because a decrease in strength and muscle mass increases the risk of injury.

My goal is not to decrease strength level by more than 10%–15% because a decrease in strength and muscle mass increases injury risk. Despite what most people think, you can build during the season. Share on XDespite what most people think, you can build during the season. One athlete joined my team weighing 119 kilos at 207 cm tall (262 pounds, 6 feet 9 inches), with 19% body fat. He could not do a single bodyweight chin-up. After six months, his weight dropped to 112 kilos (246 pounds) and his body fat to 10%, and he could perform three chin-ups with an additional 25 kilos (55 pounds).

Freelap USA: When were you introduced to flywheel training, and what are its advantages?

Artur Pacek: In 2009. My first mentor on flywheel training was Ben Prentiss at the Prentiss Hockey Performance Center in Stamford, Connecticut.

I am working on my doctorate with Mariusz Naczk, one of the world leaders in scientific publications related to isoinertial training. Professor Naczk believes that through greater antagonist activity, flywheel improves inter-muscular coordination better than classical resistance training.

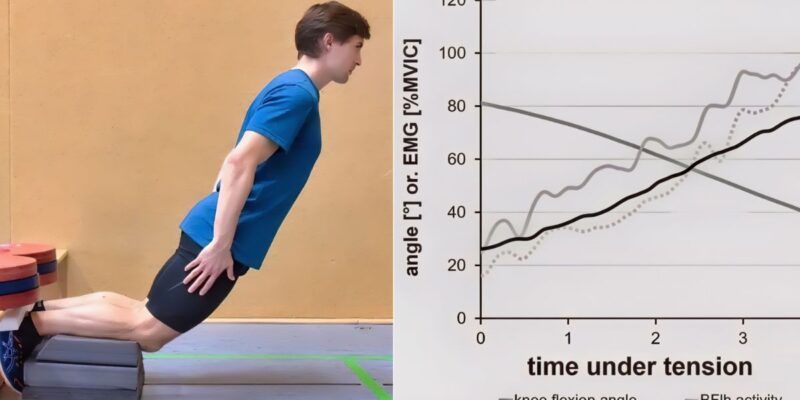

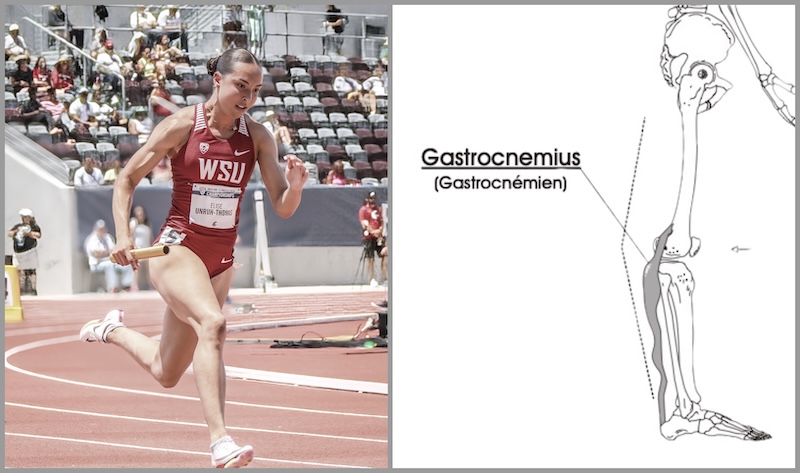

Flywheel training is unique in that it strengthens the limbs through the entire range of motion and matches the strength curves of the muscle. Further, it has a greater transfer to sports because sports consist of rhythmic motions. The flywheel teaches us to keep a rhythm, which does not occur during classical strength training. Also, the level of soreness is lower than in the classical approach, which is a benefit in-season.

From an athletic performance perspective, flywheel training bridges the gap between classical and fast eccentric training. There is an inverse relationship between force and velocity in eccentric contraction compared to concentric work. This means the slower the eccentric contraction, the lower the force you produce; the faster the eccentric contraction, the bigger the force you produce.

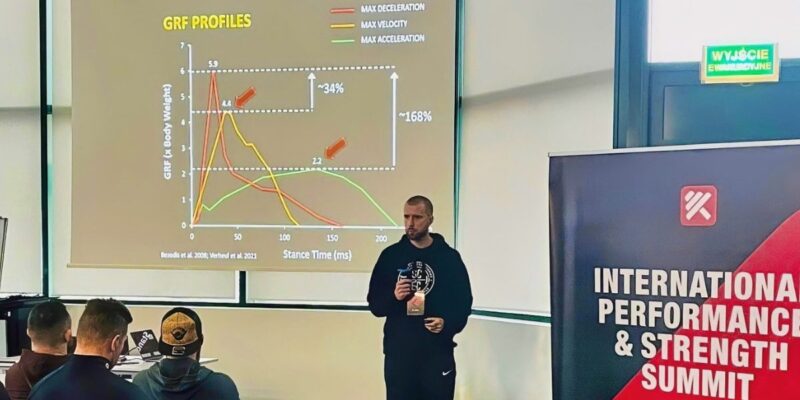

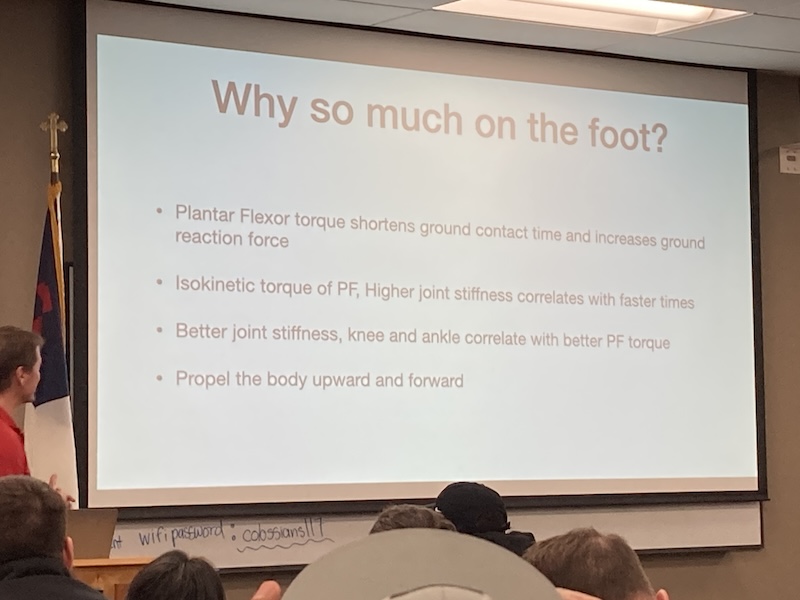

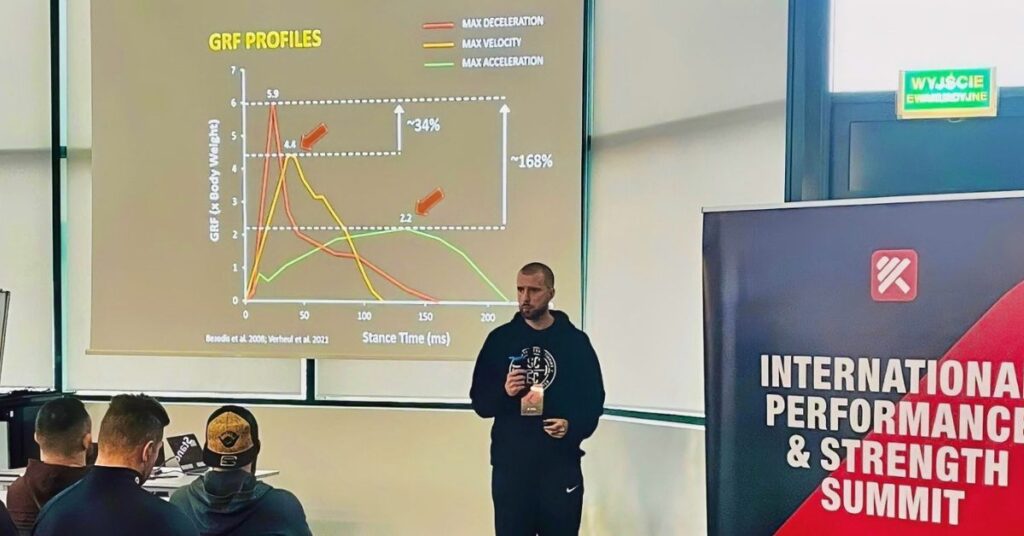

Basketball involves a lot of deceleration, acceleration, and changes of direction. During deceleration, which studies have shown can produce a force reaching 5.9 times body weight, athletes’ quadriceps need enough eccentric strength to control their posture. If not, it will take longer to decelerate, and they can strain their muscles. Flywheel training improves eccentric rate force development through fast eccentric overload. Exercises I use with the flywheel to strengthen the quadriceps and improve deceleration include the squat, split squat, and Poliquin step-up.

Freelap USA: How do you incorporate flywheel training in your workouts?

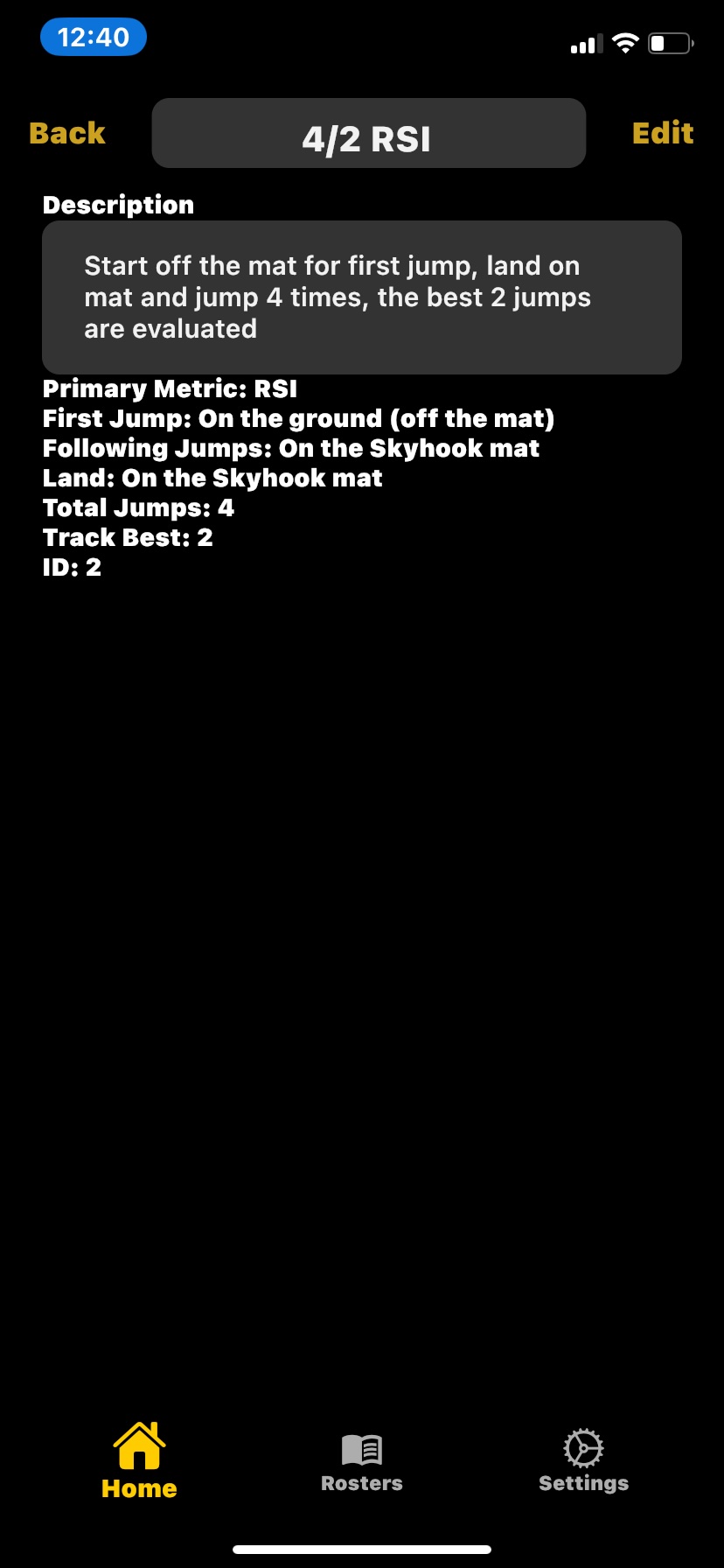

Artur Pacek: Flywheel training methodology still needs to be clarified, and it is difficult to compare it with repetitions using the classic training approach. The large wheel allows you to develop more force but at a lower velocity, whereas the small wheel does the opposite. I use both of them year-round. Here are a few examples of my workouts:

- Phase 1 – Back squat, extended eccentric

- 4 sets x 5 reps, tempo 60×0, 120 seconds rest

- Phase 2 – Back squat, overload eccentric, eccentric hooks

- 4 sets x 1+1+1, tempo 40×0, 180 seconds rest

100/70

100% = bar + hooks

70% = bar

- Phase 3 – flywheel squat, fast eccentric

- 3–4 sets x 6 reps, / – / tempo, 120 seconds rest

- Phase 4 – drop jumps from a box

- 3–4 sets x 5 reps, / – / tempo, 120 seconds rest

For the flywheel squat, I have the athletes support themselves by holding onto a bar in the concentric phase to increase force development. I also use the flywheel on game day as a great potentiating tool, such as 1–2 sets of 4–6 repetitions of fast, dynamic movements. There are many possibilities. Remember that the flywheel is a closed circuit, so the more power you generate in the concentric phase, the more power you will get in the eccentric phase.

Remember that the flywheel is a closed circuit, so the more power you generate in the concentric phase, the more power you will get in the eccentric phase, says @ArturGetBetter. Share on XI use the brand Exxentric kBox, but consider that each company has different designations for the size of the load measured in inertia in units of kgm2. I have three sizes: M–Medium, L–Large, and XL–Extra Large. When I want to develop more force, I use the larger wheels. When I want to develop greater velocity, such as on game days, I use the smallest wheel.

I want to conclude by saying that I love my job, particularly working with athletic teams. I want my players to be healthy and perform at the highest possible level. This approach helps us win!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF