[mashshare]

I recently read a great post by Carl Valle (@spikesonly) on 5 Myths About Eccentric Training Every Coach Ought to Know. When I was asked to put a blog together for SimpliFaster, I wanted to do my best to expand on Carl’s position and further put away Myth No. 4—the one that says eccentric training is only for elite athletes.

As with any other method, eccentric training for young athletes needs to be appropriately progressed and developed over time to ensure they are able to reap the benefits without getting injured.

Eccentric training has been demonstrated to be effective in enhancing performance variables. It has also been shown to be an effective means of reducing the risk of injury across a wide range of populations.

The development of eccentric force-generating capacities was recently described by Dr. Mike Young as “perhaps the single greatest determinant of physical performance” at the Exxentric Summit in Stockholm. Mike has had a huge influence on my training philosophy when it comes to the long-term development of athletes, and I’ve had the pleasure of sitting and listening to him present on a number of occasions over the last year. He is certainly convincing when it comes to the importance of eccentric strength and power when we are seeking to produce the fastest, most robust, and most explosive athletes we possibly can.

In his pursuit of the enhancement of eccentric strength and power, he has an impressive arsenal of advanced training techniques, such as momentum-based loading, e.g.: catch RDLs, supra-maximal concentrics, partial ranges using barbells and flywheel training, and shock plyometrics. These help “put the icing on the cake” and unlock what he describes as the final 5-10% of an athlete’s athletic potential after they have mastered the basics. They do this by developing a high level of relative strength and power through more traditional training methodologies means such as conventional mass-based strength training.

I work with younger athletes aged 11-18 within the Elite Performance Pathway (EPP) part of the Physical Education Curriculum at St. Peter’s R.C. High School in Gloucester, England. So I am very much in the realm of what Mike would call “baking an exceptional cake”—putting the icing on by helping athletes master basic movements and enhancing their physical development through training methods. However, because I understand what I need to do from an eccentric perspective at an elite level when the athletes are ready for it, I have been able to work backwards and start putting a thread of appropriate eccentric training progressions towards that in the early phases of the EPP system.

The EPP System: Building an Athletic Foundation

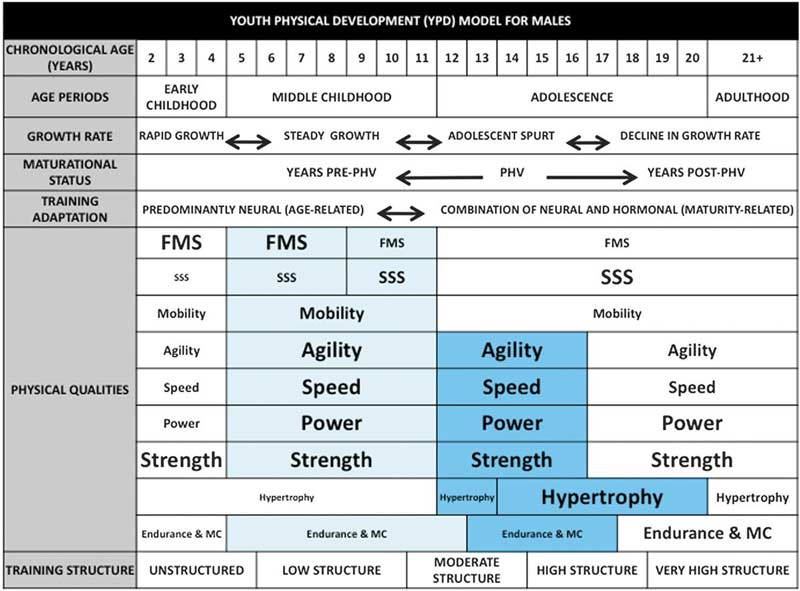

It is useful to understand the structure of our EPP system in order to provide some context as to where the eccentric training fits into the training puzzle. The EPP is a LTAD program both based around the Youth Physical Development (YPD) Model by Rhodri Lloyd and Jon Oliver (2012), and adapted from the Quadrennial Plan for the High School Athlete by Ian Jeffreys (2008). Within the age range of the athletes we work with, the key areas outlined for development are: strength, power, speed, and agility—indicated by the largest font

within the YPD Model below.

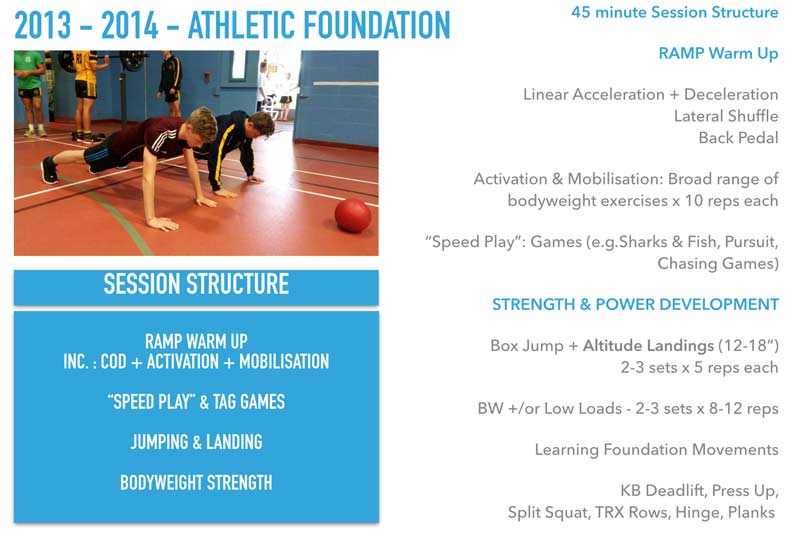

The training system begins with the Athletic Foundation phase, which is based around developing competency in fundamental movements: squat, lunge, push, pull, hinge, lift, brace, and rotate. It also includes introducing them to basic jumping and landing activities, speed play, and tag games to develop locomotive movement skills in a broad range of linear and multi-directional movements while providing a high-velocity stimulus in an engaging and challenging learning environment.

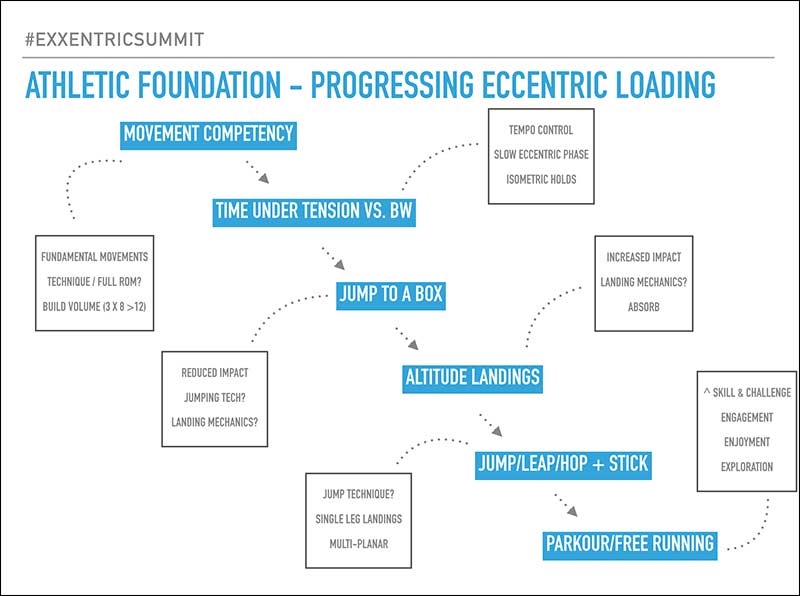

It is in the Athletic Foundation phase that we begin to introduce a small dose of eccentric training. The following diagram from my recent talk at the Exxentric Summit provides a summary of some of the progressions used within this phase of the system, and my thought processes and focus points at each stage.

Essentially, we establish movement competency first and then we build up the athlete’s ability to tolerate some volume using their body weight alone. From there, we begin to introduce variation in the speed of the execution of the movements, including increasing the time under tension with tempo controls. This includes slower eccentric phases and isometric holds in the base of squats and split squats.

Our next progression is to introduce jumping up onto an object, which provides us with an opportunity to check the athlete’s jumping and landing techniques for movement issues (e.g., knee valgus) when there is a reduced impact as they are landing up onto the box. Then we ask them to demonstrate the ability to perform an altitude landing from the box, absorbing a higher impact landing while still maintaining optimal landing mechanics.

When an athlete has demonstrated they can do this consistently over a number of sessions, we progress to jumping, leaping, and hopping by challenging the athletes to coordinate takeoff and “stick” landings for three seconds. The progressions go from landing on two feet in place, to one foot in place, and then move to linear, lateral, and rotational movements.

The jump training is often completed using a range of different tools to change the tasks and challenges in order to keep things interesting. This includes jumping between hoops, spots, hurdles, and boxes. When athletes can successfully perform the jumps and landings in place, they then begin to travel over increased distances or up onto higher objects.

At this stage, we also include activities such as skipping and playing old-fashioned games like hopscotch. These provide exposure to faster ground contacts in jumping tasks in preparation for higher intensity, fast SSC plyometrics in the later phases of the system.

While working through the jump progressions, I regularly spoke to the young athletes. Some indicated they were a bit bored with the basic jump tasks. I think it’s really important for us to understand their perspective on the training.

Connect training and game movements to keep younger athletes from being bored by basic tasks. Share on XA highly structured and controlled session may allow us to achieve our objectives, but if it’s really boring, we aren’t going to be able to keep the athletes in the program for the long term. To combat this, I have structured the sessions to incorporate a number of different elements (including the tag games) to keep the lessons going at a good pace. The various elements also provide great opportunities to connect the dots between the training and game movements, which can help athletes understand WHY they need to train through the basic movements. This helps increase their buy in.

The image below outlines a typical structure, showing where the eccentric component fits into the bigger picture of the whole session. This is based around the concept of training “all things, all the time”—where the “things” are the four key areas outlined in the YPD Model: strength, power, speed, and agility. Varying amounts of emphasis are placed on each component throughout the academic year, in order to provide a well-rounded physical development. You can see that eccentric training doesn’t have a huge part at this point, but I see it as a very important thread to keep consistently in the program because of the benefits mentioned earlier and to ensure that they can tolerate the advanced methods in the long term.

The last stage of our introduction to jumping and landing is to increase the skill, challenge, and enjoyment by allowing freedom and creativity through the introduction of Parkour/Free Running. These sessions do break away from the above structure, but the variation has provided a fantastic boost to engagement and motivation. In these sessions, the athletes can explore and combine jumping, leaping, and hopping movements with different vaults and challenges under more random conditions. In the last few months, we’ve even built a ninja warrior course using old school gym equipment—wall bars, monkey bars, balance beams, benches, and ropes—and this has been a massive hit with the athletes (and teachers).

Transitioning Into Athletic Development

An athlete will progress into the Athletic Development phase after they’ve met the major objectives within the previous phase relating to the four critical areas.

Once they’ve moved up into the Athletic Development phase, the program increases in intensity and becomes more recognizable as structured strength and conditioning sessions. We also get more time with the athletes within the school day as part of their normal timetable, in addition to their core physical education lessons.

We stick with the philosophy of training “all things, all the time,” providing a range of stimuli for strength, power, speed, and agility. However, the primary objective now is to develop relative strength and power levels through general strength exercises (squat, deadlift, bench, pull up, split squat, RDL) using higher volume set and rep schemes to start with (i.e. 3×10 reps). Then we move down the rep ranges, gradually increasing the intensity of the working loads towards sets of 6 reps by the end of the year, provided that the technique is conducive to this happening. Along with this, the speed and agility work increases in structure, complexity, and intensity.

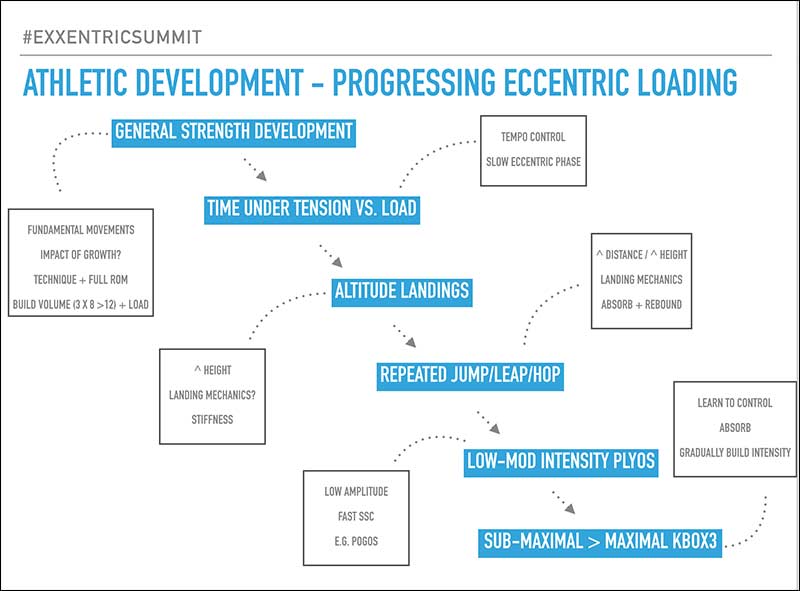

Training “all things, all the time” means providing stimuli for strength, power, speed, & agility. Share on XThe eccentric elements in the training follow suit. But, again, it progresses gradually as outlined in the diagram below, paying particular attention to any growth-related issues/changes in the way the athlete moves.

As in the Foundation phase, our first progression in the eccentric loading is to introduce time under tension, but under load in the general strength exercises. Then we increase the height of the altitude landings while challenging the athletes to increase the stiffness in landing by reducing the amount they yield at the ankle, knee, and hip on impact.

Throughout this process we sometimes re-visit the lower altitude landings, particularly if an athlete has grown considerably. This is because the changes in limb length can lead to changes in mechanics and their ability to execute the movements correctly.

The actual jump training within this phase moves on from controlling landings to repeating jumping, leaping, and hopping tasks, provided everything looks good in terms of control and stability.

The athletes are challenged here to control and absorb landings over greater heights and distances, and also to repeat them in a sequence (e.g., repeated broad jumps). In most cases, these would be classified as slow SSC jumps (>250ms).

The next stage is to introduce higher intensity plyometrics that incorporate things such as pogo jumps and low depth jumps that emphasize shorter ground contact times and aim to develop stiffness.

This year, when the athletes display competency in these progressions and a good level of relative strength in the general strength exercises, we’ve been introducing them to the Exxentric kBox3. It allows us to safely and effectively increase the eccentric overload with these athletes, working in a group environment that would not be logistically possible with traditional eccentric overload methods.

What is the Exxentric kBox3 flywheel training system?

For those that haven’t used the kBox3, it’s an iso-inertial flywheel training system that allows a wide spectrum of loading based on the fact it is dependent on the athlete/user driving the flywheel. In addition, you can increase or decrease the number of flywheels to get more of a strength or power stimulus respectively.

So, rather than working against gravity acting on a loaded barbell or similar implement, you are working against the inertia of the flywheel. The stronger you are or the harder you work, the more force you put into the flywheel and then the more it gives you back when the flywheel reverses and starts pulling you back down. But you can vary the way in which you decelerate the flywheel to create different types of eccentric overload.

Flywheel Training and the Younger Athlete

Thus far, we’ve cautiously introduced the kBox3 with only some of our athletes on the EPP. The athletes we’ve used it with all have met the following criteria:

- Excellent technique in basic strength exercises.

- Solid training history of 2+ years and aged 15-16.

- Good level of relative strength for their age in traditional barbell training (>1.0 x BW).

- Frequent exposure to eccentric loading in the form of jumping and landing.

The main exercises we’ve been using are squats, quarter squats (feet in a jump position), and lateral squats. The athlete executes them sub-maximally to begin with (i.e., the athlete only pushing with 70-80% effort), and then works to gradually absorb that force through the eccentric phase. From there, we have gradually increased the force they put into the flywheel in the concentric phase along with the speed at which they stop the flywheel in the eccentric phase.

At this point, the volume of work has been low. Typically, there are 2-3 sets of 3-5 repetitions of a single exercise integrated with the normal training program of speed, power, and strength.

Using the kMeter

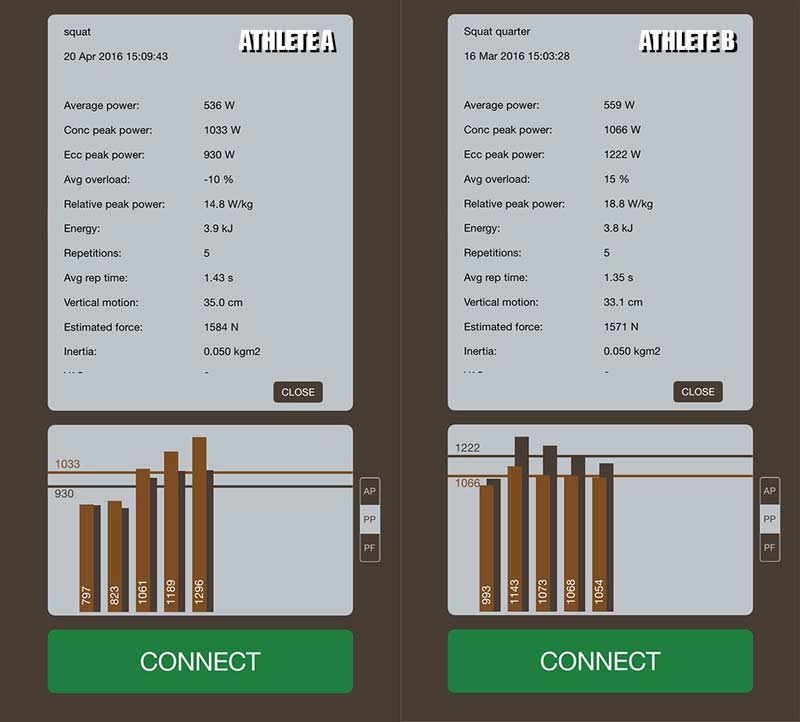

When we combine the kBox3 with the kMeter, we are also able to gain more insight into the athlete’s concentric and eccentric power-producing capabilities. Specifically, we can identify athletes who can and cannot create an eccentric overload using a standardized 5RM squat test. The two-kMeter readings below are from two different athletes. The light brown bars on the graph indicate concentric peak power and the dark brown bars indicate eccentric peak power. We should typically see an eccentric overload of at least 15%.

You can see on the left that Athlete A struggles to create an eccentric overload on the kBox (eccentric overload = -10%), whereas Athlete B regularly creates an eccentric overload here of 15%. At times it’s even closer to 25% for this particular athlete.

The data from the kMeter allows us to create a better picture of what we see when they are jumping on our jump mat. Both athletes jump a similar height of ~40cm on a no-arm depth jump from a 12” box, but Athlete A is really slow off the ground. He takes ~350-450ms to get this height, while Athlete B consistently produces the jump in under 200ms.

This ability to identify the concentric to eccentric deficit has allowed us to better select our training methods for the next phases of Athlete A’s training program, incorporating a higher volume of kBox3 and plyometric work. I don’t have the data yet, but I am really interested to see how the eccentric overload figures change for Athlete A in response to this kBox and plyometric training intervention that we’ve put in place recently.

Summary: Eccentric Training Methods Need to Be Appropriate

In summary, eccentric training is not exclusively for elite athletes. However, the methods that we select need to be appropriate to the athlete and their level of training. This starts with lower eccentric loads introduced through basic jumping and landing tasks once movement competency in basic movements is established. Following this, we can gradually increase the intensity of the eccentric overloads—keeping an eye on movement quality as the young athlete grows and matures. A tool such as the kBox3 can make eccentric overload training safer and more accessible than traditional methods, but it is prudent to be selective in its application to begin with by keeping the volume relatively low.

In addition to the methods employed, we need to consider how we design our sessions to enhance motivation and engagement for the younger athletes. Parkour/Free Running and Gymnastics are great activities to develop movement skills like jumping and landing in a more random, engaging, and challenging manner.

Hopefully, by engaging athletes we can keep them training long enough that we get to the point where we have to “put the icing on the cake.” This includes the most advanced eccentric strength and power methods, which allow them to achieve our ultimate goal and reach their full athletic potential.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]