When it comes to athletic performance, the terms “strength” and “power” are often used interchangeably.

However, they’re actually different, each playing a unique role in the way your body works and performs.

In fact, understanding the difference between strength and power is key for athletes, coaches, and trainers to optimize their training programs and get ahead of the competition.

Today, we’ll explore strength vs power, how to train for each, and the adaptations that occur with power training vs strength training.

And as a bonus, we’ll show you a cool piece of equipment that’ll change the game for either type of training…

Let’s dive in!

What Is Strength?

Strength refers to the maximum amount of force a muscle or group of muscles can generate.

It’s typically measured by the maximum weight you can lift in a single effort, known as the one-repetition maximum (1RM).

Strength is a cool concept because you might be really strong in a deadlift, for example, while someone else may be much stronger than you in an Olympic lift—different movements have different strength curves and requirements!

How To Do Strength Training

Strength training focuses on increasing the force output of muscles through resistance exercises.

Here are some key principles and methods for strength training that have been effectively used for years and years:

- Progressive Overload: Gradually increasing the weight or resistance to challenge the muscles and stimulate growth.

- Compound Movements: Exercises that engage multiple muscle groups like squats, deadlifts, and bench presses.

- Low Repetitions, High Weight: Performing exercises with heavy weights for 1-5 repetitions to build maximum strength.

- Rest and Recovery: Allowing enough time for muscles to recover and grow between training sessions.

What Is Power?

Power is the ability to exert force quickly.

It combines strength with speed and is very important for explosive movements like sprinting, jumping, and throwing.

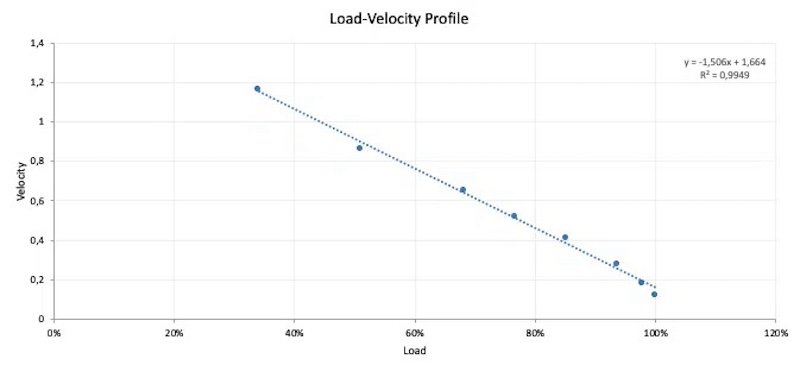

Power is often measured by the rate at which work is performed, which can be calculated as force multiplied by velocity.

How To Do Power Training

Power training aims to increase the speed at which an athlete can apply force.

Here are some examples of methods for power training:

- Plyometrics: Exercises that involve rapid stretching and contracting of muscles, such as box jumps and clap push-ups.

- Olympic Lifting: Movements like the snatch and clean and jerk that require explosive power and coordination.

- Ballistic Exercises: Exercises where the athlete accelerates through the entire range of motion, such as medicine ball throws.

- Speed Training: Drills that focus on improving sprinting speed and agility.

Difference Between Strength and Power

While strength and power are related, they serve different purposes and require separate training approaches.

Here are the key differences between strength and power:

- Strength: The maximum force a muscle can generate, typically developed through heavy resistance training with low repetitions.

- Power: The ability to exert force quickly, developed through explosive movements that combine strength and speed.

The better you understand the difference between these two, the better you can target either one in your or your athletes’ training.

What Adaptations Occur in Power Training vs Strength Training?

Both power and strength training induce specific adaptations in the body:

Strength Training Adaptations

- Muscle Hypertrophy: Increase in muscle size due to the growth of muscle fibers.

- Neuromuscular Efficiency: Improved ability of the nervous system to recruit muscle fibers.

- Bone Density: Increased bone strength and density.

Power Training Adaptations

- Rate of Force Development: Improved ability to generate force rapidly.

- Muscle Fiber Type Conversion: Shift towards more fast-twitch muscle fibers, which are more suited for explosive movements.

- Improved Coordination: Better synchronization of muscle groups during rapid movements.

What Equipment Can You Use to Improve Power & Strength?

Using the right equipment can put you in a great place for improving your power and strength training.

Here are some essential tools:

For Strength Training

- Barbells and Dumbbells: Fundamental for heavy lifting exercises.

- Resistance Bands: Useful for adding variable resistance and targeting specific muscle groups.

- Weight Plates: Key for progressive overload.

For Power Training

- Plyometric Boxes: Ideal for box jumps and other plyometric exercises.

- Medicine Balls: Great for ballistic exercises like throws and slams.

- Speed Sleds: Useful for resistance sprinting and improving explosive power.

- Sprint Timers: Using timers to build data on how your explosive training is going, such as in sprinting, are great for tracking progress. A great example is the Dashr Standard Kit 2-Gate System.

Enode Pro

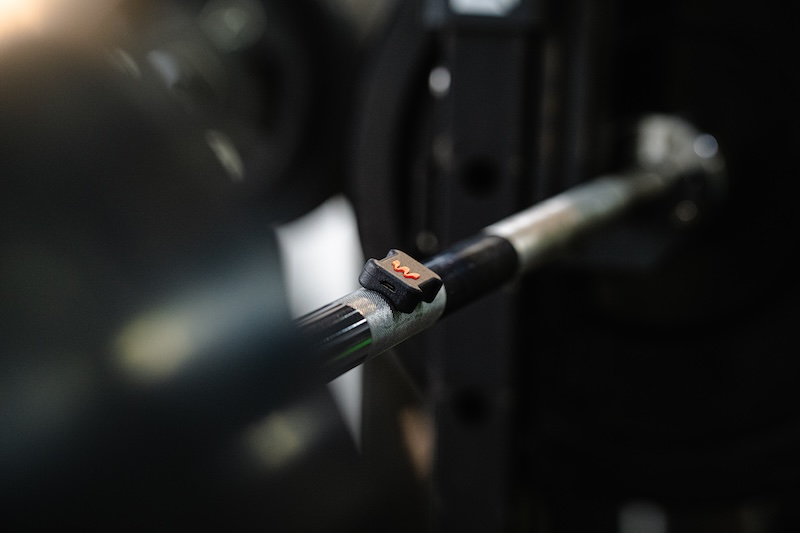

The Enode Pro is a cutting-edge tool designed to optimize both strength and power training.

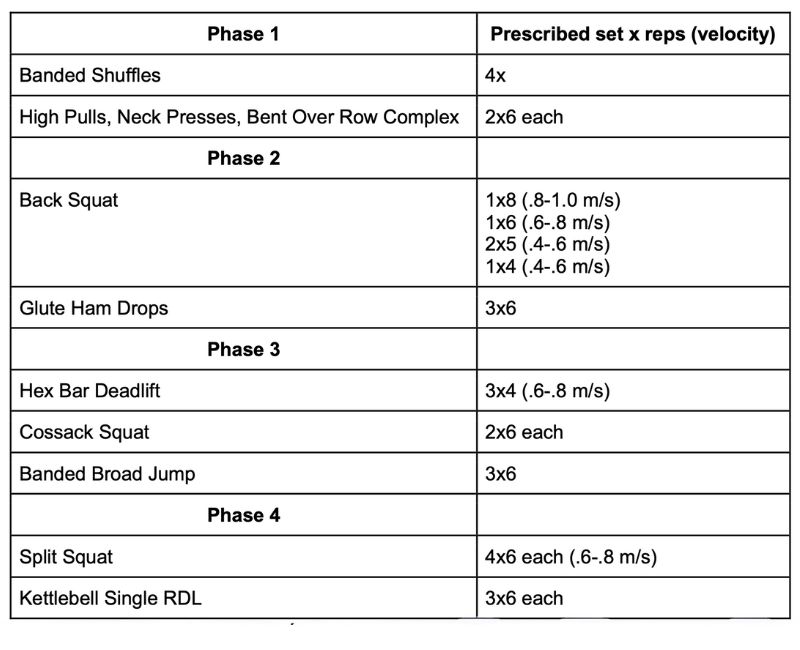

This neat little sensor provides real-time data on force, velocity, and power, allowing athletes and coaches to fine-tune their training programs.

Basically, it’s perfect for velocity-based training, which you can apply to either improving strength or power—or both!

Plus, it helps you avoid overtraining, which are common issues with both power and strength training.

Conclusion

Understanding the difference between strength and power is very important for athletes, coaches, and trainers.

It allows you to tailor your training program to focus on either strength or power, helping you reach specific athletic goals rather than taking a shot in the dark with your training.

Whether you’re lifting heavy weights to build strength or performing explosive movements to develop power, using the right equipment (like the Enode Pro), can make a big difference in how you progress.

If you want to check out high-quality training gear, make sure to visit our store!

FAQs

What is the difference between power and strength?

Power is the ability to exert force quickly and is often associated with explosive movements. Strength is the ability to exert force regardless of the time it takes. While strength is about the maximum force you can apply, power combines both speed and force.

Is strength more important than power?

The importance of strength versus power depends on the specific activity or sport. Strength is important for activities that require maximum force, such as weightlifting. Power is essential for activities that require quick, explosive movements, like sprinting or jumping. Both are important, but their relevance varies depending on the context.

Does increasing strength increase power?

Increasing strength can contribute to increased power, but they are not directly proportional. Power involves both strength and speed, so while improving strength can increase power, specific power training that focuses on speed and explosiveness is also necessary to maximize power.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Summer is a six-month strength and conditioning intern at Briarwood Christian Schools, where she assists in all aspects of the performance training program while finishing her Bachelors of Science degree in Exercise Science from Samford University. She has been instrumental in the development of programming and the implementation of Velocity-based training at Briarwood Christian Schools.

Summer is a six-month strength and conditioning intern at Briarwood Christian Schools, where she assists in all aspects of the performance training program while finishing her Bachelors of Science degree in Exercise Science from Samford University. She has been instrumental in the development of programming and the implementation of Velocity-based training at Briarwood Christian Schools.