Interest in physical education (PE) is very high at the moment, almost like a rebirth. It seems that the foundations of child development are now getting confused with sports performance training. Last year, the blog on developing physical literacy excited a lot of coaches and was well-received, but I see a disturbing trend of practices in strength and conditioning that need to either change or stop entirely. The goal of this article is to cover some misconceptions and provide a few tips for helping young athletes get better with practical and fun activities.

The Difference Between Physical Education and LTAD

Long-term athletic development (LTAD) is not the same as physical education. While they have similar needs and may look alike, the purpose of scholastic-themed PE is to help transform a child into an adult, not just provide a starting point to becoming an athlete. Coaches tend to look at the fundamental movement patterns of PE and artificially try to place them into progressions for young athletes, or sometimes older athletes. This is not a great idea.

The purpose of scholastic-themed PE is to help transform a child into an adult, not provide a starting point to becoming an athlete, says @JeremyFrisch. Share on XThe best example is bear crawls: A 45-pound child having fun in a gym is not the same as a football lineman, and the exercise literally doesn’t scale up. If an adult or teenage athlete need remedial work, coaches tend to rush to the bottom with movements that are not appropriate. Fundamentals are not a time machine, and just look at the “stuff” kids should have done. While it’s never really too late, athletes who have been exposed to activities after their “learning window closed” need to train with skills that teach a framework of coordination to the level of their strength and sport.

LTAD starts where PE ends, and some overlap certainly exists. You should not rush into any sports at all, and some kids should wait before starting organized sports until they are able to be athletes without the “balls and rules.” Don’t force athletes to do PE exercises from when they were kids as a way to fix what may not actually need to be changed much. The belief that you can’t teach an old dog new tricks is a myth, but when an older athlete misses out on foundational work, they may run out of practice time or fail to close a gap.

Youth Training Is Not Miniature Strength and Conditioning

As an owner of a private facility in a small town, I understand that to make a living you can’t just wait for elite athletes to come in the door. My facility trains everyone, from busy moms who need health and wellness, to a high school football player who needs to add size and strength. Our youth training programs are not repackaged strength training courses that the high school kids do. In fact, elementary school kids look different than middle school kids, and high school kids train with a different purpose and methodology. Being able to slowly develop a kid from 8 years old to adult allows our program to introduce the right training at the right time. What we see are a lot of strength programs that were likely not well-designed to begin with being recycled with lighter loads and simpler movements.

Lots of people warn about not adding strength on dysfunction, but many are quick to add strength before coordination, says @JeremyFrisch #youthtraining. Share on XTake a medicine ball exercise against the wall with a middle school kid. That exercise may be great for a high school athlete working on rotational power, but you are basically taking a kid who still needs exposure to more dynamic and chaotic activities and making them face a wall like a time-out. No matter the weight or size of the ball, it’s still a loaded exercise when they really need more internal exercises with their body. The same can be said for prowlers: We have heavy sleds, but kids should learn to connect their arms and legs with coordination, not try to strengthen their legs before they have control. Lots of people warn about not adding strength on dysfunction, but many are quick to add strength before coordination.

Recess or Free Play Is a Priority

Kids need more play time outside or actual activity inside. Physical education supports play—it doesn’t replace it. A modern kid plays less than kids in the past, and you can’t blame video games since board games, video games, and other distractions didn’t interfere with playing in our generation. Most of the problem we see is parents trying to get their kid ahead with extra academic activities or pushing them too hard with child sports.

Kids should be playing and having fun, not being taught how to play tennis. If they are young enough to play on a slide or jungle gym, leave the organized sports alone. Sports are not fun if you are on the bench, not interacting during a game, or not good at them. Free play allows for kids to climb trees, build a snow fort, and even make up their own games. Creativity is an endangered activity, mainly because parents are often overbearing and sometimes overzealous. For safety, an area with adult supervision is a good idea, but keep the parents on the sidelines—not the kids.

Now comes the talk about volume. A few minutes of PE sprinkled into youth sports is not the answer. Physical education is the framework of play, and it can’t replace play. Play time is homework and school work, and PE is concentrated tutoring. In the past, kids got more PE, but without general play the access to PE isn’t enough to fully evolve a child. The dangerous period is where kids are athletic enough to do sports, but not developed enough to leave play out of the equation. Play is not just for kids; all athletes should find a way to keep a few games in their life that don’t focus on keeping score.

Teach Athletes to Decelerate Themselves and Not Exercises

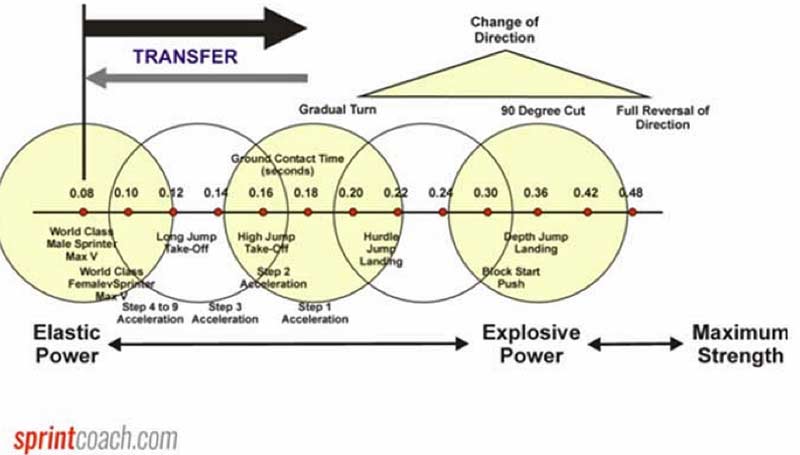

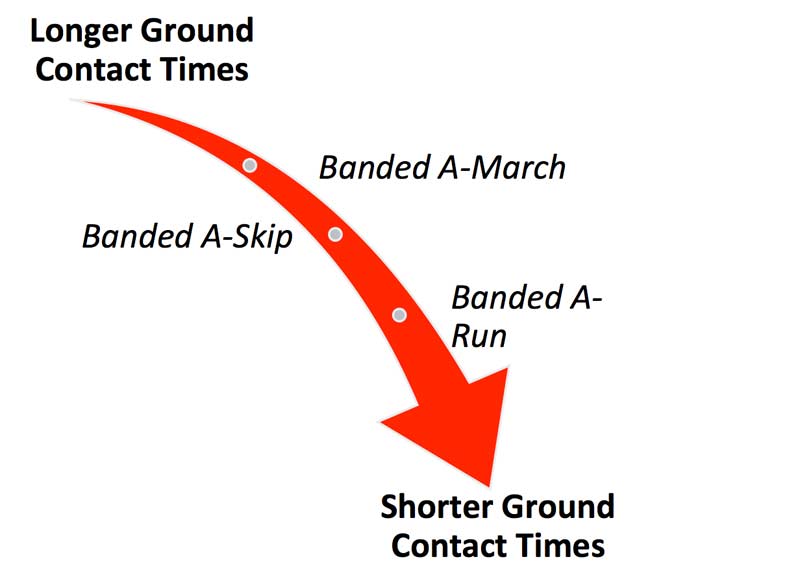

A high school kid needs to learn how to decelerate their body, not pick up a landmine exercise or rehearse high speed patterns slowly because these patterns are too static and constrained. There are plenty of age-appropriate activities that help with eccentric control to stop or change direction, so leave the watered-down stopping drills and dumbbell and barbell movements for someone else. Deceleration is about eccentric capacity and coordination, but it’s also about reaction and decision-making.

When you have kids do reps of an exercise like a strength training set or a slow-motion agility drill, it dulls their coordination. They may get better at the drill or the prescribed exercise, but it’s unlikely to help them stop on a dime or evade a defender. Change of direction and agility is a high-load/high-velocity activity and should be trained as such. Being able to stop on a dime is followed by an acceleration in another direction. Working on just stopping is only the half the equation. Before the invention of sports performance training, athletes developed agility through years of play and practice in game-like situations.

Video 1. Deceleration development is about having familiarity with braking, not using external strength exercises. It’s fine to include plyometrics and strength training as an athlete advances, but the kids need to know how to control their bodies in time and space.

At older ages, you need to reinforce the basics with technique and make sure athletes have the strength to actually perform what they are attempting. The worst thing kids can do is disrupt their power and skill ratio, where they attempt to do things they see on TV or social media without any actual rehearsal and strength training investment. The YouTube generation of athletes is not really at fault; we just need to do better at supporting them with teaching and training.

Don’t Turn Your Weight Room into an Obstacle Course

Our training area at Achieve is a multipurpose room, so we can train anyone from 8 to 80. When coaches ask what they can do in the weight room for younger athletes, I get worried about safety. Most weight rooms are organized racks and barbells, so moving those around is probably not possible. If you only have access to a weight room, it’s likely your school or facility sees athletic development as strength training.

A good coach can create challenges without buying any equipment, as an obstacle course should be about the way a child or athlete responds to a coach’s layout, says @JeremyFrisch. Share on XWith certain age groups and environments, you can only find time to keep athletes going during the season with basic strength, but those are professional situations, not developmental periods. Many of the videos at Achieve get coaches excited and they are the highlight of what I do, but we also focus on teaching smaller pieces of movement and don’t just let the kids run wild. A good coach can create challenges without buying any equipment, as the course should not be about what apparatus you buy, but how a child or athlete responds to a coach’s layout.

A research study on obstacle courses was published last year, and the conclusion was that you can use obstacle courses to appraise movement. Some studies show that obstacle courses can be used to help test aerobic fitness with young children, but I prefer using them to challenge kids with coordination and speed. America Ninja Warrior and all other courses we see in law enforcement come from challenges that can be linked to child games or military training. Focus on getting access to wide open space and giving the kids challenges. You just need a few cones to organize a fun challenge, as the equipment is not as important as the creativity and planning.

Let Athletes Have Fun—Give Them a Choice!

Activities that are open and loose engage kids because they give them freedom. Most coaches who get too caught up in programming forget that choice is one of the most important gifts you can give to a child who is used to being told what and how to do things. Having fun is expressing and making up their own games or rules. Physical education is guided discovery and has a lot of joy involved because teachers are educated on what makes an activity exciting for a child.

Choice is one of the most important gifts you can give to a child who is used to being told what and how to do things, says @JeremyFrisch. Share on XWhen a coach sees a deficit, they are sometimes too quick to try and fix something and forget that an athlete usually struggles to do an activity they don’t find enjoyable. When you spend time doing something you love, you’ll likely improve it. It’s sort of a chicken and egg concept with talent; meaning, are we good at what we like or do we like what we are good at? It’s hard to say.

Video 2. Giving kids an option to choose what they want is wise, because kids have instincts for what games they can succeed in. With enough encouragement, they will modify existing games with rules that make it fair and fun.

Voting is sometimes popular, as simply asking the group what they want to do is a great way to see what they want. Exposing kids to other activities they may not be aware of is important, because if a child or athlete is not experienced in an activity, they may not know whether they like it or not. You don’t need immediate passion from kids, but you’ll know in a matter of minutes by the smiles on their faces and laughter. Coaches may want to rethink practices when the interaction between getting work done and the enjoyment of it is not in balance.

Dodgeball Is Great and Timeless

Dodgeball is one of the most fun activities because of the speed involved. A good game can spike the heart rates of a group of high school kids up to the roof, while it keeps young kids engaged and sharp. Not many other games bring such fun and excitement. Of course, there are some who think dodgeball isn’t good for kids, but they likely just don’t understand why the game is unique.

Dodgeball is one of the few activities that transforms physical literacy into #sportsperformance, says @JeremyFrisch. Share on XDodgeball is one of the few activities that transforms physical literacy into sports performance. Catching an errant throw in sport happens all the time. In dodgeball, the ability to catch a throw that is fast and designed not to be caught is a way to get a great out. Not only does it make you more valuable in the game, it teaches athletes to catch at overspeed with difficult throws. Dodging another person becomes easier when you are dodging multiple balls traveling fast. It’s basically taking a bunch of sports and blending them, with the result of better athletes and more fun.

Video 3. Dodgeball is one of the greatest games, period, as it includes throwing, catching, deceleration, and even conditioning. Using the right equipment makes it safe and engaging.

Safety is a factor that is brought up all the time by those who think it’s a politically bad idea to allow kids to throw balls at each other. The first thing a person outside of sports will recall is a time period when the game used hard rubber balls, but now ultra-soft balls are easily purchased from Gopher Sports. Non-contact injuries are unlikely because the game is more about quickness than change of direction demands like in field sports. Dodgeball is that perfect game that seems to do everything without any real baggage.

Games of Tag Are an Advanced Activity

Tag is a great game for the development of the Vision-Decision-Action cycle. The problem comes when the game is played with athletes of varying ages and abilities. Most of the time, the best athletes will dominate, and the less-athletic ones will get less exposure to the game. Playing with athletes of similar abilities can remedy the situation but that’s not always possible.

Putting together mixed teams with athletes of different abilities can be a fun and creative way to play, as the stronger athletes can protect the less-athletic ones, giving the athletes who need it most more play time. Another way is to play team tag for time instead of elimination. That way, even if the athlete gets tagged, they are still in the game and can self-assess on the fly.

Any group of kids can play Duck, Duck, Goose or freeze tag, but very young kids don’t have the deceleration demands of college athletes. Playing tag is popular, and videos of the Celtics playing tag have gone viral and this is a good and bad thing. Not all games of tag are easy on the body and some athletes are not prepared strength-wise or skill-wise to handle tag games. If you start off with tag too early, you can accelerate the problems you have with fundamentals, reinforce what is lacking, and reward the talented.

Video 4. Tag is pure joy for kids and very easy to get started without much teaching or setup. Don’t forget that tag becomes less specific as the athlete becomes more evolved, so take that into consideration when designing training.

Tagging is a combination of speed and tracking. Fleeing and chasing are a part of physical education, but most practitioners in strength and conditioning think about the capacity or demands too much or create the wrong games that misinterpret reaction. A lot of drills and games done with young athletes are caught in limbo between wannabe PE and watered-down strength and conditioning. Merging two fields can work, but sometimes it compromises the benefits of both fields.

If you want to improve agility, don’t play games that confuse an athlete who is already matured and playing sports. To further develop an athlete, coaches should recognize that they are not position coaches and are not just weight room specialists either. Expand athletes’ capacities, and if you work with them during practice, remember not to add training that doesn’t help the sport and cuts into the development of their athletic ceiling. Rehearsing “moves” with cones and drills is limited, and most of the time it’s fatiguing and placed at the wrong time of year.

Let Athletes Jump Naturally Before Plyometrics

Remember prerequisites. Jumping is a natural expression, and only when you have a wide skill set should you think about training jumps. You instruct and guide athletes on plyometrics, but they are mainly training options for athletes. Teach jumping and let’s move on from box jumps and get to what kids need.

Treat jumping as a set of challenges and let the athletes self-discover and develop their own style, says @JeremyFrisch. #physicaleducation. Share on XHow many horizontal jumps do kids do now? Moving away from the transfer of bounding and hopping, focus on how kids can create natural locomotion. Running and then jumping is a lost technique, but when a basketball player goes for a layup or an athlete does a diving catch, they are doing something far more athletic than box jumps.

Video 5. Jumping is fun and athletes should jump for joy with challenges, not artificial progressions like older athletes. Embrace their low body weight and make jumping, hopping, and even bounding part of the equation.

It’s lazy to just grab exercises from track and field manuals or PE books—you need to learn the principles and how to coach the movement. Sometimes the movements and activities are easily picked up, but you don’t coach the group, you guide them. Treat jumping as a set of challenges and let the athletes self-discover and develop their own style. Like a sheepdog herding the sheep, you just need to worry about the slow learners.

Giving a Good Task Is Better Than Cueing

The wisdom of the body is just years of Mother Nature working smarter than a coach. Cues are fine, but what happens when you are in a group? When training athletes, realize you can’t give everyone feedback for every rep. Feedback, and sometimes correction, is a verbal exchange that may not always work or need to be done at all.

Coaches who want to help and see the problem with their eyes want to intervene. Don’t think that just because you are not cueing, the process is silent, or you can’t make a few corrections. The process of coaching is instructing an athlete to improve, not do what you see and say. An experienced coach knows what to say, what not to say, when to say it, and when to wait to say it.

Video 6. The Royal Rush game is all about natural acceleration and deceleration. Kids will find the best and smartest path movement-wise, so don’t overdo the coaching.

Failure is not losing a game. Exploration in physical education is a student trying to do different things and learning. If a student or athlete is making “mistakes” from trial and error or experimentation, they are discovering a lot about how their body responds to their environment. Repeated mistakes coupled with stagnation is where a coach should intervene with either a reminder of what’s happening or a cue to possibly correct what isn’t working.

An experienced coach knows what to say, what not to say, when to say it, and when to wait to say it, says @JeremyFrisch. Share on XLater in Part 2 I will outline the cues and art of communicating, but planning and experiments that focus on the learning of the athlete or student versus teaching from the coach are generally a better experience. Not having to talk isn’t just about talented athletes who grasp concepts easily; it’s about experienced coaches who know what to give in order for athletes to not have to be cued.

End of Part 1 and Wrap-Up

This article was cut in half, as a massive post would just overwhelm most coaches who are looking for a few nuggets of wisdom. In the next part I cover more common issues that strength and conditioning coaches should think about, and share solutions that can give answers for tough problems you face. Before I go, here are a couple of resources you may want to think about buying or at least reading to learn more about physical education. One warning though, having a few books in your library will not make you a PE teacher, as that is still a profession that requires formal education and experience in the gym.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF