This is the challenge I face with football players during the fall: competing adaptations between the sport and maintenance of lean muscle tissue, the management of stress accumulation throughout the practice week, and ensuring a player is primed for optimal performance on Friday and Saturday nights. Such tests bring out the best in us as coaches.

I have made more mistakes than anyone in the industry. From prescribing a carbon copy of Westside Barbell’s methods to my athletes to making sure I knew a kid’s 1RM before his name. Fortunately I maximize each mistake so I don’t make it a second time, and this enables me to learn faster than the competition. Many sport coaches, however, are making a mistake that is neither maximized nor eliminated: the corrosive in-season training of American football players and teams.

As soon as training camp begins, focus on preparation for football always seems to get lost in the shuffle. There are typically two schools of thought when it comes to in-season workout routines:

- Make no changes to training.

- Training will cease to exist.

These are classic examples of over and under reactions, and they will not serve your player(s) or team well. As is the case with almost anything in physical preparation, the answer “depends,” as Bill Hartman is notorious for saying.

Having worked in the private sector and in a team setting as a consultant, I’ve seen both sides of the coin. Each category presents its own advantages and disadvantages, processes and systems, programs and templates. Luckily for us coaches, neither scenario requires a master on all things regarding physical preparation. All that is required is competence or “cooks, not chefs,” as my mentor Andy McCloy would say.

Private Sector Challenges With Football Training Design

If you’ve spent any significant amount of time in the private sector, you understand that strength and conditioning at the high school level is simply not where it needs to be. Mix that with athletes entering the competitive season, and you have a recipe for disaster. Now, before I’m crucified, some coaches are doing tremendous work: John Garrish, Gary Schofield, and Fred Eaves, to name a few.

The typical measures for high school strength and conditioning coaches are situations that are ideal and situations that are not ideal.

Video 1. Lateral lunges may not sell training programs to young athletes, but if a coach sticks to their principles and teaches what the client needs, the business will come. In the private sector it can be tempting to promote flash, but focus on the basics before advanced techniques.

Ideal Situations

Simply put, ideal situations occur when coaches work toward competence. These coaches possess a sound base of training knowledge paired with experience, and they are willing to work with you as long as you are willing to be “the supplement” and not “the show.” Transitions for these athletes from practice and weights to our facility are nearly seamless. In these situations, developing sound relationships with the strength coach is essential for athlete success. We know exactly what they’re doing at school from a programming standpoint, and this shapes our template and exercise selection.

Most of the time at school, due to time restrictions and “bang for your buck,” this is the common program we see athletes performing before they come to us:

- Deadlift, Clean Variation 3-5×5

- Back Squat 3-5×5

- Bench Press 3-5×5

Now, I did not say these strength coaches are masters or chefs, but the program above is light years ahead of some of the other acts of terrorism we encounter. To supplement this program, we emphasize the dynamic effort method and move into R5 (more on the R7 protocol later). My feelings on this subject could be an article itself.

When moving submaximal weights with maximal velocity, we prescribe three-week waves with weights ranging from 30-40% 1RM. A typical three-week wave would look very similar to this:

- Week 1: 10×2-3 at 30% (explosive)

- Week 2: 8×2-3 at 35% (speed-strength)

- Week 3: 6×2-3 at 40% (strength-speed)

We attribute our success with the dynamic effort method in-season to three factors:

- Velocity recovers everything.

- Rate of force development or power increases.

- With their circa-max effort reps at school taking anywhere between 4-6 seconds to complete, the dynamic effort sets (2-3 reps) take nearly the same time to complete. These methods complement each other nicely in that regard–the players blast through sticking points at school and get more powerful at our facility. Everyone wins.

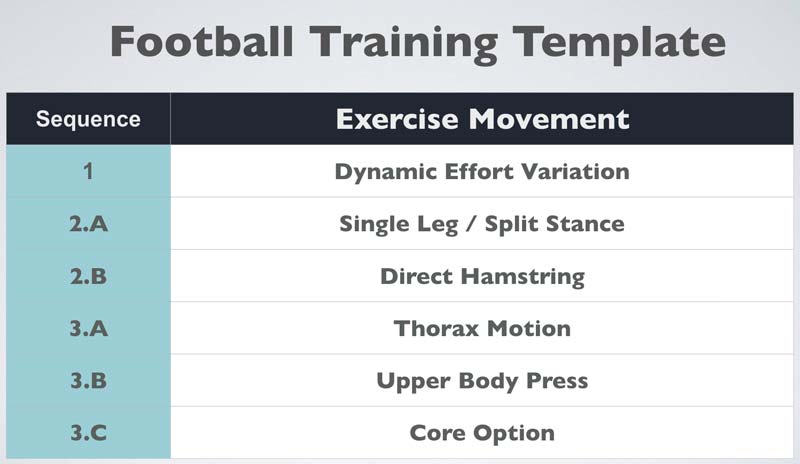

Moving into the accessory work is just that–accessories. We do not major in the minors. However, this segment is still important as it provides movement, variability, and capacity. As Mike Robertson would say, “Accessory lifts are our insurance policy!” Speaking of my friend Mike, we prescribe his accessory template exactly, and you should too.

- Accessory Superset 1

- Single Leg, Split Stance 2-3 sets

- Direct Hamstring 2-3 sets

- Accessory Superset 2

- Thorax Motion 1-2 sets

- Upper Body Press 1-2 sets

- Core 1-2 sets

Aside from the dynamic effort method, accessory work is a lost art in high school strength and conditioning. This is where we truly feel we make a difference in not only an athlete’s success but also in their resilience.

Accessory work is a lost art in high school S&C. It impacts an athlete’s success and #resilience, says @huntercharneski. Share on XAccessory lifts provide variability to a population that is notoriously rigid. When football players are exposed to “the big three” on a regular basis, their rigidity levels spike, which substantially increases prime mover output but at the cost of lessening degrees of freedom. Luckily, supplementing their school program with accessory work increases their degrees of freedom which in turn increases stabilizer output. Win/win.

Here is our in-season R7 template for ideal situations:

- R1: Release–three areas

- R2: Reset–Supple Leopard mobility, breathing, FMS corrections

- R3: RAMP–wall drills, arm mechanics, posture, and position

- R4: Reactive–acceleration, COD, max velocity, chaotic agility

- R5: Resistance

- R6: Reminder–cyclical movements

- R7: Recovery–supine diaphragmatic breathing

Non-Ideal Situations

Non-ideal training situations are those where training has come to a screeching halt or has seen no decrease in volume or intensity at the onset of camp. Simply put, these athletes are in survival mode. For better or for worse, at our facility we’ve chosen to adhere to the least common denominator given the circumstances by prescribing aerobic circuits comprised mainly of concentric movements (upper and lower body sled drags, medicine ball throws). To show a template for this situation would be unrealistic, as the needs of these kids become so individualized that the entire session is purely autoregulation from start to finish.

These poor kids are living “in the middle” by coaches adhering to the more work, less time philosophy. In non-ideal situations, often it’s not exposure to high intensity that hinders the athlete but repeated efforts in a submaximal, lactic environment with inadequate rest periods. This alone is how we justify our modified sessions for these players, as the aerobic environment will increase capillary density like tributaries forming off a river.

Smaller capillaries forming off major blood vessels will slow blood flow. And, if we’re able to do that, blood will stay in contact with the tissue longer. This heightens waste product removal and nutrient transfer. More importantly, as this workout generates heat, there will be a decrease in the electrical impedance which will increase motor unit activation. Over time, all these motor units will develop characteristics of white fiber (fast and explosive). The accompanying sleds and throws will introduce a brief high-intensity component, but any soreness will be peripheral rather than central since these are concentric movements.

Other pain points that we encounter in the private sector include:

- Negative alterations in movement technique because weights (at school) are too heavy.

- Enhanced levels of fatigue because of the immense stress placed on the muscles.

- Insufficient learning of technique because coaches emphasize the weight put on the athlete’s back, chest, or floor.

- Little-to-no physical and technical preparation for performing the movements.

In my opinion, a laser focus on skill execution will alleviate all four of these points. In other words, the weights prescribed to the athlete and the strength they gain should be directed toward improving the skill or sporting activity, not pure strength alone, regardless of skill execution or sport improvement. Simple concept, yes?

Unfortunately, common sense is not so common these days. When coaches prescribe heavy weights, it’s nearly impossible for athletes to focus on proper execution of the lifts. The athlete’s attention shifts to simply overcoming the weight which can lead to bad habits which can lead to injury. If coaches understood this, many athletes would be healthier and achieve higher levels of success.

The Team Environment

My experience in team settings has always been as a consultant. That in itself can be considered a pain point, as only so much of your message and suggestions are taken and then applied (any of my friends in the industry who consult can surely attest to this). Why? Coaches and players are worried about three things:

- The game

- The product they put on the field

- Wins

I’ve always found this extremely interesting since a college football player’s time spent in the competitive environment (the game) is only 8-10% throughout the year. They spend 23% of their time in mandatory days off and 67% in physical preparation. These figures beautifully illustrate “process over product.” Perhaps we should develop tunnel vision in the process, so the product will then take care of itself.

The first conversation I have with coaches is about the structure of practice. American football, from a bioenergetics standpoint, is an alactic-aerobic sport. Yet practice plans rarely meet the demands of the appropriate energy system. The “more work, less time” philosophy rears its ugly head once again, as 24-30 plays run in two five-minute periods and place the athletes smack dab in “the middle,” or lactic, environment.

When athletes train in a lactic environment, they move too slowly to develop speed, says @huntercharneski. Share on XDerek Hansen has said that players will spend less than 3% of the contest in the lactic zone. I’ve said it before and I will say it again, when we expose our athletes to a lactic environment, they are moving too slowly to develop speed, and they are moving too fast to develop work capacity. It’s truly a waste of valuable practice time. Of course, the sport coach is attracted to this zone. Why? As Derek Hansen has said, it comes down to two points:

- Coaches believe it’s high-intensity work.

- It provides an immediate, tangible effect.

I’ve implemented a system with coaches where we walk thru a majority of plays on the script to aid in learning and keep players out of the middle. Walking thru plays also serves the team well on a neurological level. When the body is learning a new motor skill, (or in this case, the game plan from week-to-week) the initial result is typically crude and atrocious. So why have them perform these new tasks at full-speed? To change a motor behavior, we have to get the brain’s attention; to get the brain’s attention, we have to slow things down.

During these initial stages of learning early in the week, the brain tells the players what to do by sending signals through the nerves down to the muscles that are involved in executing the skill. Repetition after repetition, along with coaching cues, notifies the brain of the execution. Through both visual (film) and auditory evaluation and correction, the brain once again sends signals to the players’ muscles for execution. The execution then improves.

Video 2. Breathing drills are sometimes difficult for athletes and must be coached and programmed just as well as any other exercise. Football players are very good at repeated explosiveness, but activities that relax the body are just as vital for performance.

This feedback mechanism continues until a more or less permanent feedback loop is formed. As the week progresses, I suggest you sprinkle in more full-speed reps. This aids the process of skill correction and acquisition on every repetition. Then through film study and practice, the skill improves over the course of the week until it becomes more automatic.

This is where the magic happens. As the end of the practice week approaches and the skills acquired become more automatic without brain involvement, the feedback loop moves to the spinal column. This loop now circles from the muscles to the spinal column, back to the muscles. Since the brain is no longer involved, the skills and game plan are nearly automatic. When the signal is received, the muscle memory kicks in, and the loop occurs without hesitation. Throughout the week, players have canceled the noise and enhanced the signal a la Derek Hansen.

Low-Volume, High-Intensity Training

Unfortunately teams across the nation are detraining throughout the year because they don’t provide enough high-intensity work. I know I must sound like a hypocrite, as I just explained how low-intensity practices can benefit performance. But how I could I ignore sprinting since I have such an affinity for it? How do we incorporate high-intensity work in a practice setting without taxing the players and inhibiting optimal performance on Saturday? We microdose absolute speed.

Microdose Absolute Speed

Derek Hansen has told me on more than one occasion, “You only need three good runs.” With that, I’ve simply suggested to the coaches that they microdose three good runs over the course of the practice week. For those unaware, most college football practice weeks consist of full practices on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday and a walk-thru on Friday. Again, it’s not a difficult or complex concept to implement. We advised coaches to have the players give one max-velocity sprint of no more than 30 yards during each of the full practices. Three good runs.

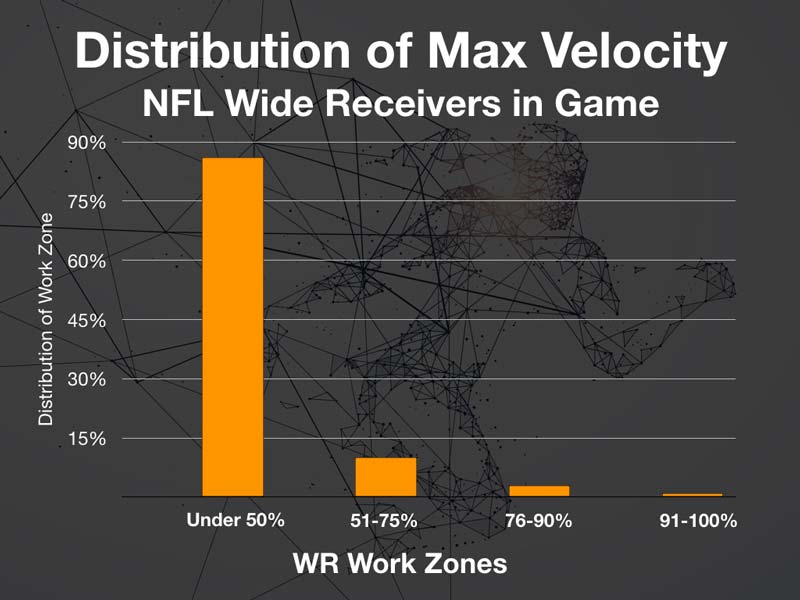

Microdosing absolute speed throughout the week is of the utmost importance for not only maintaining and experiencing a positive adaptation of speed capabilities but it also prevents injury. Whether an offensive lineman has to reach top speed on a screen play or a cornerback intercepts a pass and proceeds to “house it,” having exposure to max velocity will ensure their health.

If players are not exposed to max velocity, their neural recruitment patterns will be impaired as their central nervous system does not know how to handle absolute speed. Do you believe the ungodly number of hamstring injuries reported this early into training camp are a coincidence? I rest my case.

The Speed Reserve

The maintenance of speed capabilities also contains a conditioning effect–the speed reserve. Derek Hansen’s explanation is as profound as it is simple, “The higher your maximum speed capabilities, the greater ability to run sub-maximally at higher velocities for longer durations.” With a typical football game, a player will only reach speeds above 91% a mere one percent of the time. Yes, 99% of a football game is played at submaximal speed. Speed increases endurance, but endurance does not increase speed.

Weight Room Adjustments for In-Season Training

As we shift gears to the weight room, we focus on high force, high velocity. As you’re reading this, it would not surprise me if you have a blank stare on your face. You’re trying to reconcile how an athlete can produce a high force at high velocity. As much as I would love to alleviate your concerns on this matter, it’s beyond the scope of this article. For more information, read High Force x High Velocity = Optimal Power on my blog.

Buddy Morris told me that having players overcome weights between 55-80% of their 1RM is the perfect complement to the sport; they are indeed displaying high force production at high velocities, and I believe Buddy.

- R1: Release–three areas

- R2: Reset–Supple Leopard mobility, breathing, FMS corrections

- R3: Resistance

- R4: Reminder–cyclical movements

- R5: Recovery–supine diaphragmatic breathing

Due to heavy practice, meeting, and school schedules, college players’ stress buckets are near full. We’ve found it prudent to utilize only five R’s twice per week to gain the intended effect without overreaching a la Bruce Lee.

There is no need to rush strength, especially in-season, says @huntercharneski. Share on XI have encountered situations in which coaches, and my younger self in previous years, placed a premium on maximal strength during the season. In these instances, I’ve suggested the coaches only train their athletes above 85% once per month, as the training residual for maximal strength is 30±5 days. There is no need to rush strength, especially in-season. Keep in mind, the quicker you gain strength, the quicker you lose it. The slower you gain strength, the longer you will keep it.

Video 3. Medicine ball throws are not just ways to kill time, they are effective ways to teach coordination and power simultaneously. Adding medicine ball throws in-season will not create fatigue that hampers game performance.

Neurological Reset

Lastly, I want to touch on the concept of neurological reset in the team setting. The day before a game, we’ve implemented three medicine ball throw variations (high force, high velocity) to potentiate, or excite, the players’ central nervous system:

3-point medicine ball throws

- 1 set, 4 reps

- Mimics beginning movement from a static start

Between-the-legs scoop tosses

- 1 set, 3 reps

- Mimics acceleration

Backwards/Overhead Tosses

- 1 set, 2 reps

- Mimics top speed

These throws and their variations are found in James Smith’s Applied Sprint Training. More and more research has shown that the excitement of the central nervous system can last for several hours. I believe that throws are the method to use as they are extremely brief, almost 100% concentric, and produce the intended effect.

Conclusions

In-season does not mean out of training. It’s still an important aspect of player development, performance, and success. In the private sector, it’s about finding a common happy medium between two radical ends of the spectrum. In the team setting at the college level, in-season is the realization that the process truly does outweigh the product.

Regardless of the market, situation, or level of competition, I believe the modern approach instituted by many coaches comes down to one word: fear. Fear is synonymous with ignorance, and it can motivate, or it can paralyze. Coaches are afraid to say “I don’t know,” but they’re not afraid to be rather cavalier with their players, which leads to mistakes–big ones.

Search for information outlets, seek those who are doing it correctly, crawl out of your lactic threshold, and maximize mistakes by learning from them.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Good stuff. Might want to justify why supple leopard and FMS specifically. Also blood flow section may need a rework. Sounds physiological and I get the message but some of the specifics are miles off correct. Didn’t get the concentric movements causing peripheral rather than central fatigue either.

Pardon my ignorance, please interpret the following numbers for me.

Deadlift, Clean Variation 3-5×5

Back Squat 3-5×5

Bench Press 3-5×5

Set, reps. and ?

3-5×5 = 3-5 sets of 5 reps