[mashshare]

Do you ever have those days when you don’t want to work out? I do, and the older I get, the more often I feel that way. Usually, though, I end up working out anyway. Sure, the session with the foam roller is about 10 minutes longer than normal, and my warm-up seems like it takes longer than the actual workout. But there is still a lift to do, and just because I don’t feel like doing it that day doesn’t change the fact that I need to get it done. The more I think about it, if I only worked out on the days that I really felt like it… well, I’d look and feel a whole lot worse than I do now.

Does that mean that those workouts are perfect? Of course not—but I get them done anyway. Working with mostly college-aged athletes, I always laugh when they tell me they can’t work out because they don’t feel like it today. Really? I have been lifting at least five days a week for almost 30 years, played five years of college football, and have been competing at powerlifting, strongman, and weightlifting for over a decade (which has taken a toll on my knees and back).

For me, there is the added stress of working 50 or more hours a week at my full-time job and another 20 hours on my business, writing books and articles, plus living on and managing a 40-acre farm… all of which can suck the motivation from anyone. Oh yeah, and I am also the proud papa of a wonderful 2 ½ year old who runs nonstop. All this, and my athletes are the ones telling me that they don’t feel like lifting? Right. I so badly want to tell these 18- to 22-year-olds to trade lives with me for a day and see how much they feel like training.

But, of course, I don’t. As a professional strength coach, my calling is to help people become better versions of themselves. This means that when I am given an opportunity, there’s going to be a lesson taught so these younger athletes can learn from my experiences. Remembering back to what I was like at that age, I can’t blame these athletes for not understanding how narrow their view really is, or having strategies to grind through things they don’t particularly want to do.

Think about it for a second: When you were at that magic college age, didn’t you feel relatively good all the time? I know I sure did. That is the time when your body produces your own personal cocktail of gonadal steroids and adrenal androgen agents. It’s as simple as this: When people are in this primed training environment, they can recover, grow muscle, and lean out faster than at any other point in their adult life.

At that age, what were the major stresses in your life? Mine sure weren’t my job, mortgage, children, or the health concerns of family members. They were getting a date, figuring out how to afford the newest video game, and getting my homework done on time. As I said, this is the age when you should be mentally and physically feeling good most of the time.

When you constantly feel good, it makes everything easier, especially training. You can walk into the gym at 6:00 a.m. or 7:00 p.m., after a night out or not, and still salvage a decent workout. Unfortunately, the day comes where you walk into the gym and you just don’t “feel” quite right. Your knees might ache from yesterday’s squat session. Maybe you slept on the couch last night and your lower back hurts. Or maybe you got dumped by your longtime girlfriend or boyfriend.

The scenarios are endless, but ultimately there is one decision to make. Are you going to work out today? Over the years, I’ve heard two very different ways people ask that question. Some ask, “Do I feel like lifting today?” while others wonder, “So, should I lift today?”

How Changing the Wording Changes the Question

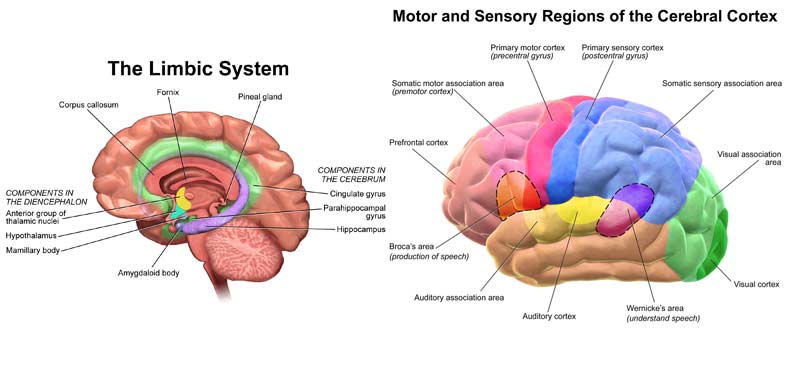

At the heart of both questions is a simple choice to make about whether or not to lift. But changing the way you phrase the question also changes the process of how you reach your answer. Asking if you feel like doing something involves the most primitive area of the brain’s limbic system.

This region oversees the most basic of bodily functions, like controlling your heart rate and breathing, governing primal instincts such as being hungry or finding people attractive, and making decisions that either give you pleasure or avoid pain.

Asking if you should do something, on the other hand, involves a different and more evolved part of the brain: the cerebral cortex. This part of the brain surrounds the limbic region and is responsible for what you’re doing right now—communication, conscious thought, and information processing would not be possible without a fully functioning cerebral cortex.

The cerebral cortex’s relationship to the limbic region is both figuratively and factually significant, since the cerebral cortex is the higher power in regard to your brain. It can override the primal urges for immediate gratification or for running away from possible pain. In our case, if the cortex has a specific process or plan, then it can overrule how you feel that day and decide to move some weight or not, as long as there is a framework set up to engage the cerebral cortex and its reasoning process.

Goal-Based Decision-Making

Your training goals for the day, either hypertrophy or performance, will determine what sort of questions you need to ask. When you train for hypertrophy, the goal is to have specific muscles grow in size by varying the combination of reps, rest, or weight, which overloads and fatigues the muscle. The classic hypertrophy training idea is four or more sets with 8-12 reps per set, all done with 90 seconds or less between sets. Weight or resistance is adjusted, so if you cannot get eight reps you take some weight off the bar, and if you get more than 12 reps you add more weight to the bar.

Workouts like this cause a fatigued state in the localized musculature for two main reasons:

- First, the primary muscles involved have a significant decrease in the carbohydrates stored (muscle glycogen).

- Second, the chemical that provides energy for muscle contractions (phosphocreatine) is used up.

The bad news is that because you are fatigued, you won’t be as strong when you finish with the workout until your body has a chance to recover. The good news is that skeletal muscle is really good at recovering and replenishing both muscle glycogen and phosphocreatine, meaning you can recover from hypertrophy workouts relatively fast. You might be really, really sore for a few days, but from the view of an exercise scientist, your muscle glycogen and phosphocreatine will be back to their pre-exercise levels in hours—which technically means that you are recovered.

Your training goals for the day—#hypertrophy or performance—determine the questions you need to ask, says @CarmenPata. Share on XIn other words, you don’t feel like lifting. You’re sore and beat up, with another high-volume leg day in front of you. It would sure be nice to have some objective way to see if you are really not ready to lift, or are simply feeling sorry for yourself.

You’re in luck—I have one and it’s the secret I’ve shared with the athletes I work out with. Believe it or not, most of it is just a simple checklist. For the people who train solely for hypertrophy, deciding whether or not to lift is sort of easy because of these factors. Here is the checklist I use with people to see if they are ready to have a high-volume hypertrophy workout.

| READINESS QUESTIONS | Yes | No |

| 1. What was your morning heart rate? ________________________ | ||

| 2. Was your morning heart rate within 10% of your average heart rate? | ||

| 3. Did you go to bed before midnight? | ||

| 4. Did you eat breakfast this morning? | ||

| 5. Did you urinate at least 6 times yesterday? | ||

| 6. Do you feel ready to destroy this workout? |

For me, the five yes/no questions in the checklist determine whether someone is ready for a hypertrophy-type workout. Let me explain my rationale. Resting morning heart rate is a good indicator of recovery and overall body stress levels as long as it’s done the same way every day. Here is my personal morning routine and what I suggest to others:

- Wake up.

- Go to the bathroom.

- Drink a glass of water.

- Sit down for at least 10 minutes in a quiet spot and think about the things you’re grateful for and what makes you happy.

- Use the app Instant Heart Rate on your smartphone to take your heart rate. Write it down, or use a program like Google Sheets to keep your records and get your average.

Working with mostly college-age athletes, I know that it is not the duration but the start or onset time of sleep that is a good indicator of sleep quality. That’s why I ask if they went to bed before midnight. Checking if people had something to eat for breakfast should give an indication of whether their muscles have been primed with some carbohydrates before working out. In my mind, getting something to eat—even if it’s a Pop-Tart—is still better than nothing.

Hydration status is represented with the urination question, and though it makes some people giggle, it is a down-and-dirty (pun intended) way to figure out if people are getting enough water. Finally, you have to account for the social, emotional, and intellectual stress that people are experiencing, which is the reason for the question revolving around people’s feelings.

To proceed with your normal lift, you must score at least three of five checks in the “Yes” column. If there are more checks in the “No” column, I give people an alternate workout. I let them pick what exercise or exercises to do, but they have to follow these guidelines.

- Med balls or kettlebells only.

- No more than 4 total sets.

- No more than 10 reps.

It’s a really low volume (<40 reps) workout compared to what they would typically get (32-48 reps per exercise), but that’s the point. Their alternate workout is a de-load. They are in the gym, getting some work in, and setting themselves up for a great workout tomorrow.

Performance Training and the Autonomic Nervous System

I mentioned that most of the people I work with are college athletes, and for this population, becoming faster and better at their sport is the goal of training—any hypertrophy that happens is a by-product of training. With that in mind, the question of “should I lift?” changes from determining if they are physically ready to grow to instead determining whether they are ready to be as fast or powerful as they can be. Again, you have to make sure the body is ready, but if you look to the muscles for this answer, you’re starting at the wrong place: You have to go much deeper than the muscles.

You must look deeper than the muscles to determine whether the body is ready to lift, says @CarmenPata. Share on XWhen your body is not under stress, it functions in a state referred to as the “rest and digest” or parasympathetic state. From an evolutionary viewpoint, when you are in this parasympathetic state, your body is getting ready for the next time you have to run or fight to escape from a dangerous situation. Like the name suggests, this is when the body can repair itself: digesting food, canceling out stress hormones like cortisol or adrenaline, and conserving energy with a lower heart rate. When you are in this state, it is easier to think and do work that requires a steady hand.

The counterpart to the parasympathetic state, “fight or flight,” is how the body functions under stress. When you are in the fight or flight—or sympathetic—state, you are experiencing all the benefits and drawbacks of having your body primed for physical activity. Your heart rate and breathing increase, sending more blood and oxygen to your extremities and getting ready for activity. Stimulants like epinephrine are released into your body, causing your pupils to dilate so you can see more of the world. Adrenal glands begin to secrete the hormone adrenaline so you have a boost of energy if you need it.

Being in this primed physical state for activity comes at a cost. Non-essential systems, like digestion, are nearly shut down to provide blood and energy to the rest of the body. Your ability to process complex ideas or your fine motor skills are greatly impaired as well. Think of it like this: If a lion is chasing you for lunch, do you need your digestive system to process your breakfast, or do you want as much extra energy as possible to help keep you running fast until there is someone else between you and the lion? Once you’ve survived the lion attack, then you can rest and your body will have time to finish digesting your breakfast. Make sense?

Thankfully, we don’t have to run from predators in our daily life anymore, but our bodies haven’t figured that out and still respond the same when we feel any sort of stress. Physical, emotional, and psychological stress, as well as stress from trauma, all trigger the same response from our bodies. This wouldn’t be an issue if there was enough time to rest and recover from each stress event, but that isn’t the way modern life works.

We have rush hour delays and congested traffic. We stay up later, sleep less, and are exposed to more varieties of stress than our ancestors could even dream of. When you are constantly exposed to all of these stressors and are not given enough time to let your body get back to its rest and digest state, how do you know when you are ready to train to be fast or powerful?

Simple. You check your nerves. As you’ve read, when you are exposed to a stressor, you shift to a primed physical state, which is what you want for training. But if you remain in this stressed state for too long, your nerves become overloaded and it takes more time to signal your muscles to contract. What all of this means is that, although your muscles are full of muscle glycogen and phosphocreatine, you will still train like you are weak and slow. To keep this in check, I have athletes use this version of the readiness questionnaire, which has two very important additions.

| READINESS QUESTIONS | Yes | No |

| 1. What was your morning heart rate? __________________________ | ||

| 2. Was your morning heart rate within 10% of your average heart rate? | ||

| 3. Did you go to bed before midnight? | ||

| 4. Did you eat breakfast this morning? | ||

| 5. Did you urinate at least 6 times yesterday? | ||

| 6. Do you feel ready to destroy this workout? | ||

| 7. What was your pre-warm-up tap or jump? _____________________ | ||

| 8. What was your post-warm-up tap or jump? _____________________ |

The big changes are in questions 7 and 8. When athletes are scheduled to execute workouts that demand they be near their absolute best and fastest, we have them get a baseline reading of their nervous system.

Most people like using an app on their phone called SpeedTapping, which has a rectangle that you have to tap as many times as possible in 30 seconds. The other option is to use a Just Jump pad and get a countermovement jump score. Either way, their test gives my staff and the athlete a glimpse of how their nervous system is functioning. After their warm-up, but before the athletes begin their lift, they re-test. If their score is higher than their baseline, which it should be, then they continue their lift as normal.

Every once in a while, their post-test is actually lower than their baseline. Think about it for a second: They perform worse after warming up than they did before warming up. Besides violating every training theory about an active warm-up improving total body function, this drop in performance tells me their nerves are not functioning at their normal levels and the athlete is in no way capable of training at a high level that day.

However, instead of letting them walk out the door, I have the athletes do a recovery-style workout, with 20-30 minutes performing a very low heart rate (<110 beats per minute) activity like walking, biking, rowing, or swimming. This is followed by 10 minutes with a foam roller and a good stretching or yoga session, and then they can call it good for the day. I’ve found that performing these easy, recovery-type workouts usually does the trick, and the following day their taps or jumps are back to normal.

From Readiness to Results

So, what does all of this mean? Whatever the goals of your workout session—becoming as big as a mountain or setting a new personal record—it’s about getting results. When you go to the gym, you should figure out what will be the greatest return on your time, effort, and sweat. Deep down, the root of the problem is that our brains just don’t want us to do more than what we need for our body to survive, let alone put itself in a fatigued state from working out.

Therefore, you have to make a choice. In that moment of choice, we truly become the paragon of all life on the planet, because human beings are the only ones that have that ability. Choosing what to do with our potential is the privilege and the price we pay as human beings. After all, a tree can only be a tree, but it will always grow as tall as it can. A cheetah can only be a cheetah, but it will always run as fast as it can. You and I are different, though. We can not only decide how much of our potential we will use, but we can also decide what we will remake ourselves into.

While we have this power and choice over what we will do, at some point everyone’s motivation wanes, and the temptation to skip a workout begins to creep up on us. Having a plan (or in this case, a checklist) to see if you are really ready for a training session, rather than listening to your feelings tell you “not today,” is a powerful tool. Think of it this way: Your feelings are just information, they are not instructions. Just because you don’t feel like it on a given day, doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t lift, but that you need to take a closer look to see if you are ready to lift.

A plan that determines your #readiness to train is a powerful tool that can override your feelings, says @CarmenPata. Share on XIf all the signs are yes, except for your feelings, then at any point you can override what you are feeling, which is something you already do many times each day. I get it—going into a heavy deadlift workout is not the same as holding back your inner Hulk and not smashing the printer when it has a paper jam. But, then again, it sort of is. You are making a choice to ignore your primal feelings and instead listen to your rational thoughts.

If you are anything like me, sometimes you just need someone or something to come along and push you out of the funk of feeling sorry for yourself because you don’t feel like lifting. In that case, think of these readiness surveys like your own personal Hans and Franz: They’re “here to pump you up!,” making sure that at the end of the workout you are one step closer to the person you want to be.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014”. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons.

Trending Resources

Building a Better High Jump: A Review of Stride Patterns

How We Got Our First Sprint Relays to State in Program History

Science, Dogma, and Effective Practice in S&C