When people think about rotational power, golf should be near the top of the list. Unfortunately, it probably doesn’t even crack the top five. If you were to list your top rotational power sports, you probably would put golf somewhere around ultimate frisbee and frisbee golf. It’s a leisure game, right? Is it even a sport?

Golf’s low ranking on most people’s rotational power lists is likely due to the old stereotype of beer-drinking, cigar-smoking business guys making deals on the course and swinging a club between. So why am I, a guy who trains golfers exclusively, writing on the topic of rotational power training and the latest considerations to think about? Because times are changing and the speed you swing the golf club could mean millions of dollars.

Sports Science and Golf – Building Golf Athletes

Golf may be behind when it comes to sports science and the mentality of the majority of people who play and follow it, but it is evolving quickly. Most of the Sunday broadcasters and weekly morning show hosts still believe weight training makes golfers slower and that it destroyed Tiger Woods’ career. They believe all golfers should exercise with bands and do exercises that mimic the golf swing. Meanwhile, most of the top players in the world are looking more than ever to sport science for an edge, and the industry of golf fitness has exploded.

Anyone watch the 2019 Masters at Augusta? Yeah, Tiger’s career was not destroyed by strength and conditioning. In fact, it is the reason he was able to pull off one of the greatest—if not the greatest ever—major championship victories in history. When it comes to discussing rotational power and the best way to train these athletes, the challenge is that there is about as much agreement on how to train it as there is debate on whether weight training is good or bad for golfers.

For those of you who don’t know, rotational power in golf is expressed in one metric and one metric only: club speed. No matter what side of the strength and conditioning divide that people sit on in the game of golf, they all agree that club speed matters. There is a definite and clear relationship between average drive distance and how high on the money list a player is.*

* Ball speed ultimately determines how far the ball will travel, but factors such as quality of contact, what part of the club face hit it, spin rates, launch angle, etc., all come into play. Raw physical rotational power in golf is more easily measured by club speed with the other elements of ball speed and total carry distance removed.

This has led to a plethora of devices, training aids, protocols, and “quick fixes” to increase club speed with as little effort as possible. Unfortunately, many of these are poorly researched (if at all) and they are often taken as a training item in isolation, instead of as part of a comprehensive, long-term training approach. Many rotational sports have this issue, so golf is not alone. There are countless disagreements about the best type of training to make the greatest improvements in what ultimately matters: performance on the course and rank on the money list.

Many of the devices, protocols, etc. used to increase club speed are often taken as a training item in isolation, instead of part of a comprehensive, long-term training approach. Share on XMy goal for the rest of this article is to dig into the nitty-gritty of what the science says and what it doesn’t say, and hopefully help both sides start to see the light at the end of the rotational power training tunnel.

What Type of Strength Training Is Best for Rotational Power?

To start, let’s just say that there is no single best training program to maximize rotational power across all athletes. There are, however, certainly principles and methods that reign supreme and boxes that you can put athletes into to create the best customized programs for them. When it comes to training rotational power, the options are endless as to the type of programs you can run, the training schemes you can modify, and the variations of exercises that you can throw at an athlete. Based on our research over the past couple of years, we have found that the program that works is dependent on the athlete and where they are developmentally, among other things.

Our initial two-year research study1looked at junior to senior golfers (over 600 data points) and evaluated what type of training mechanism would impact club speed the most positively. We put all subjects through a conventional, periodized, and progressive program for one year, and then the next year put all of our athletes (from junior to senior) through a triphasic program.

Our goal was to see if there would be a difference, and the results were quite interesting. Over any given 12-week period during these two years, junior golfers (10-17) could expect to see, on average, about a 3.08 mph swing speed increase (equivalent to 8-10 yards gained off the tee). Adult golfers (18-70) saw, on average, about a 1 mph increase in any given 12-week period (equivalent to 3 yards gained off the tee).

The really interesting findings, however, came when we compared how each age group performed in the different workout program periods. There was a 50% better result in club speed for juniors during any given 12-week period compared to the 3.08 mph average when they were on the traditional periodized program. When this same age group was on the triphasic program, they experienced an underperformance to the 12-week average improvement in club speed of 10%.

The adults experienced a 40% improvement in club speed relative to the 12-week average when they were on the triphasic program. They conversely saw a 12% underperformance to the 12-week average when they were on the conventional training program.

These findings should incite some serious thought when it comes to deciding what type of training program to put a rotational athlete on (or any athlete, for that matter). When selecting and creating a program to improve an athlete’s power output (and ultimately, their performance), we need to pay attention to their biological age, as well as their training age, and also consider where on the strength-speed continuum they are.

My interpretation of these findings is that the more traditional model allows for improved “newbie gains” and gives the younger athletes the opportunity to build through volume, movement competency, coordination, and base levels of strength. The triphasic program appears to work best with post-pubescent younger adults up through senior golfers who have had a level of training experience with muscle mass developed at one point in their athletic career.

Since completing this study two years ago, we have seen continued positive results with our golfers. Our younger golfers have continued to see improved rotational power development by focusing on traditional progressive loading while they are young in training age. For them, the goal is to focus on building a foundation, athletic skills such as jumping, sprinting, etc., and overall coordination.

As they mature both biologically and with training, shifting to the triphasic program with a large focus on post-activation potentiation has continued to produce power and club speed gains year over year. As an example, we have golfers who have gained speed every year for the past six years, with some well into their 70s. It is rare that a golfer does not gain speed, and even more rare that one loses speed when we retest our golfers yearly with this approach, no matter their age.

Does Rotational Power Training Have to Be Golf- or Sport-Specific?

The short answer here is that no performance training program will ever be as sport-specific as the sport itself. Hopefully, we can agree on that much. A recent randomized clinical study among collegiate golfers found that “golf-specific” exercise does not have an impact on golf performance any more than traditional training does.2Perhaps the problem is the terminology.

What if we reserved “sport-specific” and “golf-specific” for when we talk about playing the actual sport and practicing the technical skills required to win at it? This would free us up to be specific about what we are actually training.

Are you training the kinetic sequence or output of your athlete? Or perhaps the kinematic sequencing is what you want to address? Perhaps you are looking to train power specific to the sport’s demands that is correlated (based on objective data) to sport-specific power output (i.e., club head speed or sprint speed) that directly correlates with outcomes in competition (wins and money)?

I think this would clear up a lot of confusion as to how a back squat, a cable chop, an end range active shoulder external rotation drill, and a clean pull are all “golf specific.” Just my two cents…

Another study we recently completed on eccentric flywheel training3showed that training up rotational strength definitely improves club speed even beyond what our initial two-year study showed. In our initial study looking at the triphasic and traditional models, we just utilized traditional rotary training methods, including bands, a Keiser cable machine, and medicine balls. In this follow-up flywheel study, however, we actually compared results when some athletes did eccentric overload training rotationally on the kPulley system by Exxentric, while other groups performed rotational exercises with bands and cables. The results were pretty compelling.

The group that used the eccentrical flywheel for rotational training had a 150% improvement in club speed relative to the study average, in half the time. Share on XThe group that utilized the eccentric flywheel for rotational training saw almost a full 1.5 mph improvement in club speed above and beyond the initial 12-week average we had found in our initial two-year study—and this was only over a six-week training period. Percentage-wise, this is a 150% improvement in half the time. That is huge and definitely something that you should note when you look to increase rotational power in a meaningful way.

I want to be clear that the rotational exercises we completed did not have athletes with a club in their hand or mimicking the golf swing. They were not “golf-specific” by industry “Instagram” terms. We instead made sure that athletes focused on rotational power output with proper kinetic force production and technique. By doing this, we looked to drive the most efficient kinematic sequence possible; hopefully resulting in the greatest amount of power output possible. We did this objectively by utilizing the Bluetooth technology in the kPulley system to give us immediate feedback on how the athlete was performing.

So, What Type of Rotational Exercises Work Best?

Like the majority of coaches today, I used to focus all our attention on programming details (i.e., systems focus, macros/mesos/micros, etc.) of the big four and Olympic lifts. When it came to auxiliary lifts (which rotational training often falls into, for some reason), I would magically forget that systems training and goals still applied. I would just do what I thought was “golf- and sport-specific.”

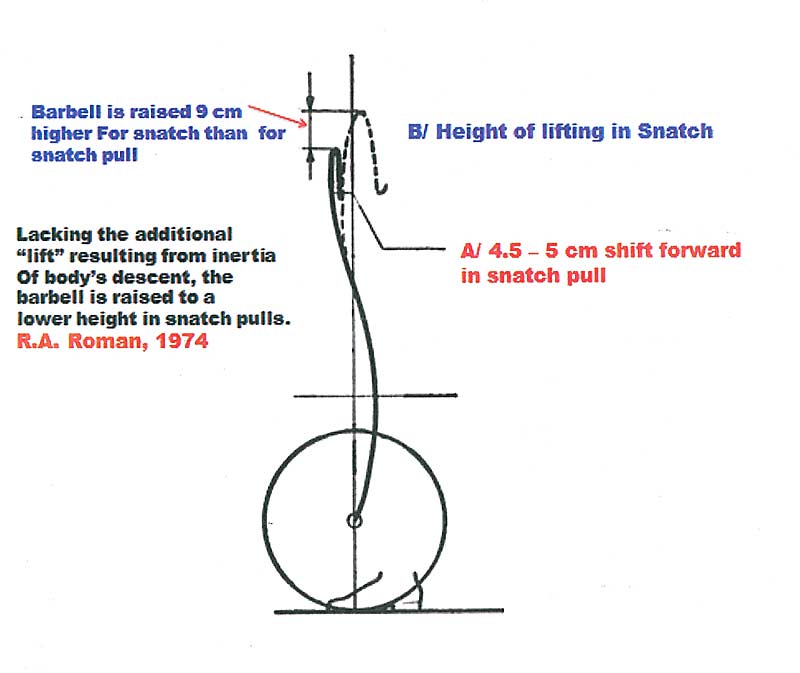

Having seen the results from our research, I now program our rotational lifts in conjunction with our other training goals, and the results have blown us away. For example, with our adults in a triphasic program, we start our rotational lifts with progressively heavier loads as we decrease volume (similar to traditional periodization) through the eccentric and isometric phases of the program. The goal during these phases is to maximize rotational strength and improve the body’s ability to store and absorb forces in rotation.

I now program our rotational lifts in conjunction with our other training goals, and the results have blown us away. Share on XIt is important to pay attention to the quality of rotation your athlete uses, particularly with the trend for rotational strap training. In video 1, I demonstrate the typical athlete’s move when you tell them to go as hard and fast as they can. Because the line of pull is horizontal on most cable machines (or kPulley in this video), the tendency is to drive laterally first. You can see the huge lateral lunge with an upper body lean that follows, and I even almost lost my balance—this is pretty common.

Video 1. Enhancing a rotation with lower body movement adds a layer of potential transfer. Invest in combining rotation and various leg driving patterns.

In video 2, you can see the correct sequence and loading that you should coach, with an emphasis on horizontal drive from the legs happening first, followed by torsional drive to clear the hips, and then finishing with vertical to the lead leg. Depending on your belief about leg dominance in creating power (keep reading), you can even cue which leg to drive through more.

The big difference in the two videos (besides the sequencing of the kinetic drive) is also the relative quiet upper body in video 2 compared to video 1. An athlete—particularly a very strong upper body athlete—will be tempted to use their upper body to create those speed and power numbers. We need to be on the lookout for this compensation and not be stuck with our eyes only on the screen telling us the raw numbers. Be sure to pay attention to how your athlete is creating those power numbers.

Video 2. The use of isoinertial flywheel loading is great for rotational power. This movement takes a few sets to fully grasp, but after that an athlete can learn to catch the eccentric load and be smooth with the hip snap.

When we move into our conversion to power phase, we go lighter on the flywheel and focus on the speed and explosiveness of reps. We also start to utilize lighter medicine balls to encourage speed as we approach our in-season phases of training for the year. It is important to continually track in-session peak power and speed outputs during this phase. It is possible to go too light with the flywheel and lose the desired peak power and speed numbers. Using the technology available in the kPulley is a strategy to combat this potential training inefficiency and error.

Speaking of Medicine Balls, What’s Their Role?

Well, the research is pretty clear, no one really knows how or why medicine balls work, but it appears that they do work to increase speeds in rotational athletes.4I choose to use medicine balls like all of our other training tools. In the off-season, we look to periodize their use with more volume and slightly higher load balls (perhaps 10-12 lbs.) to train up strength and resilience for the season to come. As the season approaches and the athletes start to play more, we start to use less volume with a focus on speed and explosiveness.

This transition to lighter balls with more speed in the rotational plane does not mean athletes lose focus on total power production. We are just attempting to maximize power output from the speed element of the equation, compared to earlier in the off-season cycle where the strength and resilience side of the equation was our focus. That being said, we are acutely aware that the load in a medicine ball is far below the threshold to truly be considered a power training implement. Instead, for real power training, we use clean pulls and other traditional methods where true meaningful load can be applied to the system to achieve the desired nervous system effect.

Similar to using the Bluetooth sensor in the kPulley, we utilize the technology of the Ballistic Ball by Assess2Perform to track the speed of our athletes’ throws. This gives us objective information as to how the athlete is performing.

Kinetic Specific Training

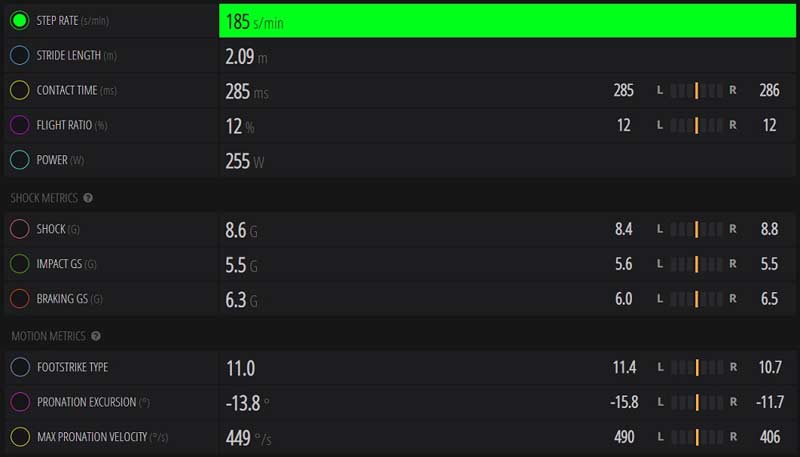

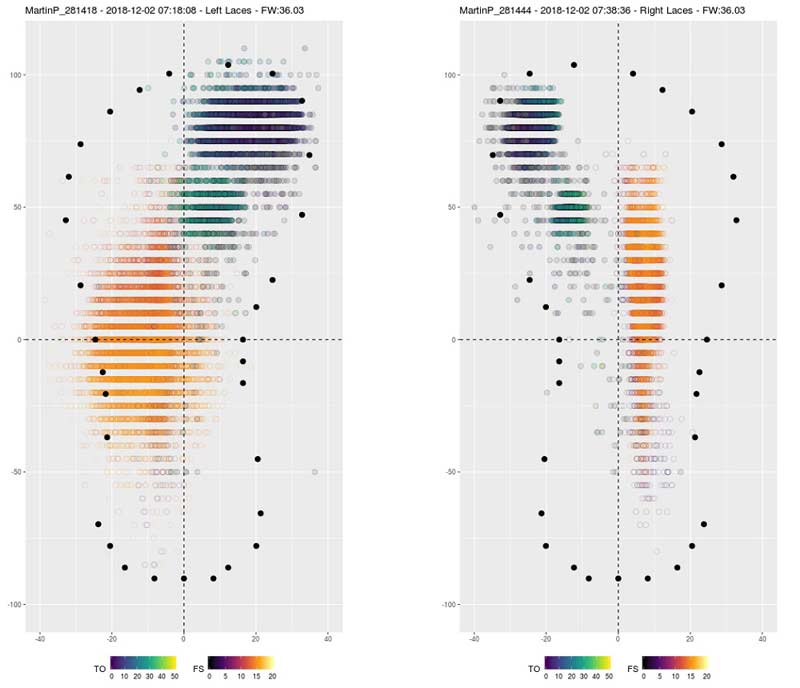

A common flaw that we see in rotational training with medicine balls, cables, flywheels, and band training is a severe lack of attention to coaching the athlete on how to use the ground maximally.

A common flaw in rotational training with med balls, cables, flywheels, and band training is a severe lack of attention to coaching athletes on using the ground maximally. Share on XIn videos 3 and 4, you can see with use of the Ballistic Ball that the athlete is initially able to produce just under 3 m/s with a rotational Iron Man throw (as we call it at Par4Success) with minimal use of vertical force (she doesn’t load into her trail leg vertically). She primarily uses torsional and horizontal forces.

Video 3. Concentric throws with no wind-up or loading phase have less velocity than countermovement throws, but are great for golf athletes.

But when we cue the athlete to start with the ball over the lead shoulder and load it diagonally into the trail side before throwing it, her speed jumps over 2x. By using a simple cue such as this, we are able to significantly increase the resultant necessary vertical force that would have to be produced, with the horizontal and torsional forces also increasing in sequence to throw the ball. We have seen this happen in both elastic and non-elastic loading scenarios while on force plates.

Video 4. Adding momentum increases the velocity of the throw with skilled and prepared athletes. You can compare concentric to countermovement throws to evaluate how athletes are able to use their coordination.

If you work with golfers, 99% of them kinetically sequence horizontally to torsionally, and then vertically. It is my belief, based on instances such as the one shown here, that it is critical to make sure we train athletes to sequence correctly kinetically to get the most out of our rotational exercises. Tools such as the Ballistic Ball and the kPulley are incredibly valuable to measure and give immediate feedback to an athlete and a coach for measuring improvements long-term. They are also valuable for educating athletes on how proper use of the ground can create incredible improvements in their output on the course.

Kinetic-specific training, not sport-specific training, is where the rubber hits the road in rotational power training. Share on XKinetic-specific training, not sport-specific training, is where the rubber hits the road in rotational power training. Tools that allow you to measure kinetic force output (force plates) or resultant speeds due to improved kinetics (such as peak speeds or power outputs as in the video above) are an incredible asset to any coach’s arsenal. The latter category is likely the one that is least cost-prohibitive for most coaches, but an understanding of kinetics would be a prerequisite in order to maximize efficiency of these tools’ uses.

Ground Reaction Force and Personal Power Profiles

We see incredible gains in club speed immediately by assessing a golfer’s leg dominance and kinetic force preference and coaching them to match their swing to their ability right then without any physical training. There is a mounting body of evidence that the better an athlete can produce ground force, the more power they will be able to produce in their golf swing.5,6

Here is a recent case example:

- During his swing, a 35-year-old golfer shifts his weight 90% to his trail leg (right) on his backswing (based on pressure mat readings).

- He primarily uses vertical kinetic force to create his club speed (based on SwingCatalyst force plate data).

- He employs a swing methodology of trying to create as much x-factor as possible (tries to create as much elastic effect as possible by separating his upper and lower body maximally).

When physical testing is completed, it is noted that he is left leg dominant in the vertical plane and, according to his force generation curves, he can create a lot of power but takes longer to do so (he is not very efficient elastically). He also has a swing speed 8 mph faster on his left-leg-only swing as compared to both legs together or right leg only.

The following cues are made:

- Only shift about 50% of his weight to his right leg on his backswing (to increase load on his left—dominant—leg at the start of the downswing).

- Lengthen his backswing by minimizing separation and letting himself fully rotate into his right hip (to increase the amount of time in his downswing to reach his full force creation, since he has a slower rate of force generation).

- Try to drive up off his left leg through impact (maximize his vertical thrust focus on his dominant leg).

This resulted in an immediate 10 mph increase in club speed (30 yards) and much improved consistency in face control, which is incredibly important for accuracy in golf. The subjective report was that it “felt easy.”

This demonstrates, in a case study, a simple example of what could potentially become incredibly valuable to not only golfers, but all rotational athletes. By starting to understand what our athletes’ natural preferences are, how good they are at harnessing elastic energy, and what kinetic preferences they may naturally have, we can potentially make immediate improvements in their sport without any training in the gym. Since this is proving to be true in the swing, the intriguing question on my mind is what if we trained the athlete toward this preference even further in the gym, with all of their rotary exercises? Would this example athlete get even better if I cued left leg vertical drive in all rotational drills? His speeds on the Ballistic Ball definitely increased in the gym when we did this…

Conversely, what would happen if we trained up athletes’ weaker performing kinetic abilities? In this case, that would be the horizontal and torsional kinetic force generation.

The future of rotational power training lies in the ground, and how we train our rotational power athletes to maximize the power they can create from it. Share on XThese questions are unanswered, and I could find no research suggesting one or the other. But this, in my opinion, is where the future of rotational power training lies. It lies in the ground, and how we train our rotational athletes to maximize the power they can create from it.

Other Considerations with Golf Performance Training

In the rotational world, especially golf, there is definitely a lot of talk about training the opposite side to improve rotational performance, but I tried to find studies on this and found the research is a bit scant. In theory, it makes sense, and we often train opposite in order to try to maintain balance because golf is such a one-sided sport (at least, that’s what we rationalize). Its performance benefits are not necessarily clearly defined, and I am not sure I could honestly say any of my athletes produce more power because they train the opposite side.

In our earlier research1 we did note that an opposite-handed shot put throw had an r value of over .8 relative to club head speed (equivalent to the r value for the strong-sided shot put). This certainly suggests that being able to produce power on the opposite side rotationally is important. I am not sure, however, if it means more-coordinated athletes will generate more speed or if it is an actual indication of the importance of opposite training. It probably is a bit of both, but no one really knows at this point, as far as I can tell.

Another interesting topic to briefly cover is overspeed and underspeed training, which has become wildly popular in the golf performance world lately. It has a longer standing history in baseball and track and field (incline and decline training), where there is definitely a lot more research on it. I will elaborate in a future article on our findings on this method of training, but our initial research suggests that we can likely achieve similar speed gains with much less work than most protocols on the market suggest.

The takeaway here is to be wary of how much load you put on your athlete and always be aware of how big of a “cup” their nervous system has, so that you don’t overload them and cause their cup to spill. You need to consider injury risk when looking at high-volume protocols (90+ swings 2-3x/week), particularly in the context of the overall training program and where this type of training fits into the broader year-round periodization cycle. Also consider where athletes are on the strength-speed continuum. Does your athlete need to get stronger or faster, and how much room do you have left in their “cup” for these skills to be trained?

Post-Activation Potentiation Training

Post-activation potentiation (PAP) is an interesting topic and a staple of our training programs with our golfers. We pair every big four strength move focused on creating maximal force (squat, hinge, chest press, pull) with a power move in that same kinetic plane. For example, after a heavy squat, we might do a jump variation, and after a heavy hinge lift, we might do an explosive triple extension exercise.

There is interesting research that actually showed an immediate improvement in club head speed when golfers completed vertical jumps prior to swinging.7This study obviously looked at the acute impact of PAP, but it definitely is a point for rotational athletes to think about.

Use Real Training Practices with Golf Athletes

To wrap it all up, the simple equation of power = force + speed is not necessarily that simple. When it comes to rotational force production, strength training in the non-rotational patterns is clearly important and produces significant swing speed gains.1But coaches need to be aware of athletes’ biological and training ages, as well as their individual needs. If you put them in the wrong strength training program, you actually can slow down their gains by up to 12%.

It appears you can potentially magnify the sport-specific rotational power metrics (swing speed) by training rotational strength eccentrically. This does not mean to train this in isolation; rather, do it in addition to the traditional big four training to maximize the training benefit. We need to move beyond solely utilizing low-load rotational staples such as medicine balls and bands and into the world of rotational overload training for maximal results.

When using medicine balls and completing rotational exercises, be sure to give feedback that helps athletes understand the impact of how they use the ground, and its effects on their outputs in competition. Improper use of the ground can lead to an athlete producing half the speed they are actually capable of every rep. This is a huge wasted opportunity if we, as coaches, do not pick up on it and cue properly.

Improper use of the ground can lead to an athlete producing half the speed they are actually capable of every rep. Share on XThe future of rotational power training is still quite gray and there are few, if any, definites in the literature. Hopefully, this article sparks some questions in your mind, and inspires you to go and find the answers to these questions with your athletes.

Golf-specific training is also a confusing gray area for athletes and coaches. Starting now, be acutely aware of how you train rotational strength, speed, and power, both kinetically and kinematically. Plan how you will periodize it. Research how you will measure it. Perfect how you will cue it. Prove empirically that how you are training it is working. Then teach the rest of us how you are doing it.

References

1. Finn, C., Prengle, B. and Cassella, A. Research Driven Golf Performance Training, Par4Success. October 2018, pp. 3-20.

2. Hegedus, E.J., Hardesty, K.W., Sunderland, K.L., Hegedus, R.J. and Smoliga, J.M. “A randomized trial of traditional and golf-specific resistance training in amateur female golfers: Benefits beyond golf performance.” Physical Therapy in Sport. 2016; 22: 41-53.

3. Finn, C., Prengle, B. and Cassella, A. Eccentric Flywheel Training and Its Effects on Club Speed in Golfers: A 6 Week Study. Par4Success. April 2019, pp. 2-10.

4. Szymanski, D.J., Szymanski, J.M., Bradford, T.J., Schade, R.L. and Pascoe, D.D. “Effect of twelve weeks of medicine ball training on high school baseball players.”Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2007; 21(3): 894-901.

5. Leary, B.K., Statler, J., Hopkins, B., Fitzwater, R., Kesling, T., Lyon, J., Phillips, B., Bryner, R.W., Cormie, P. and Haff, G.G. “The relationship between isometric force-time curve characteristics and club head speed in recreational golfers.”Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2012; 26(10): 2685.

6. Read, P.J., Lloyd, R.S., De, S.C. and Oliver, J.L. “Relationships between field-based measures of strength and power and golf club head speed.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013; 27(10): 2708.

7. Read, P.J., Miller, S.C. and Turner, A.N. “The effects of postactivation potentiation on golf club head speed.”Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013; 27(6): 1579.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

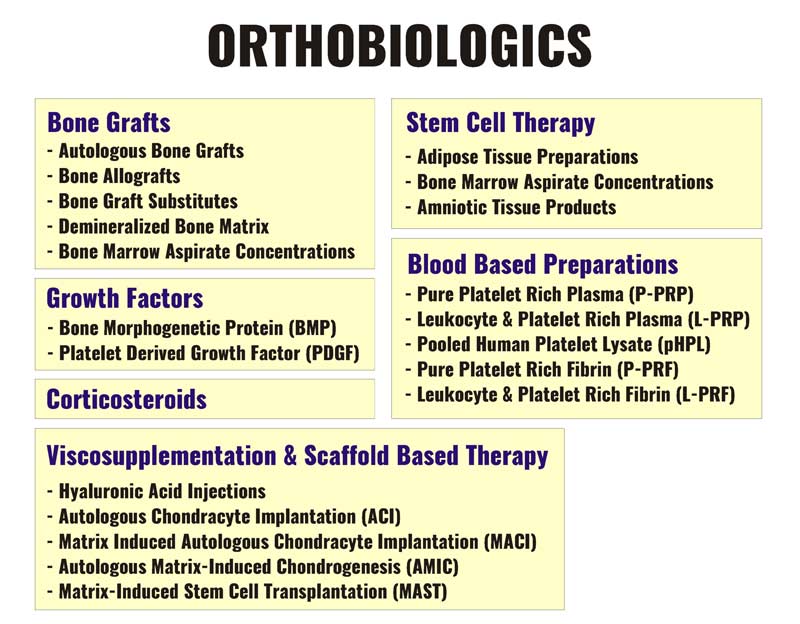

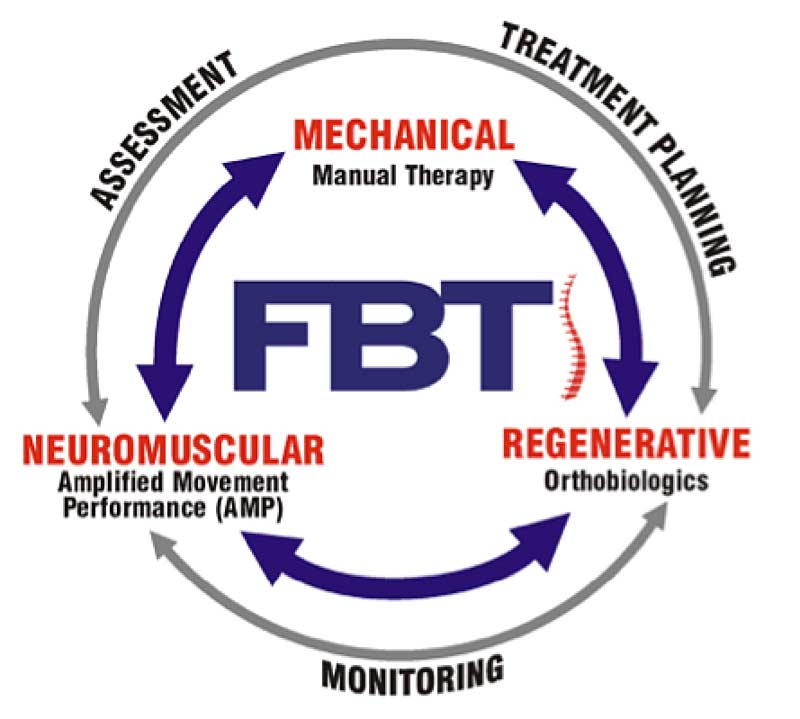

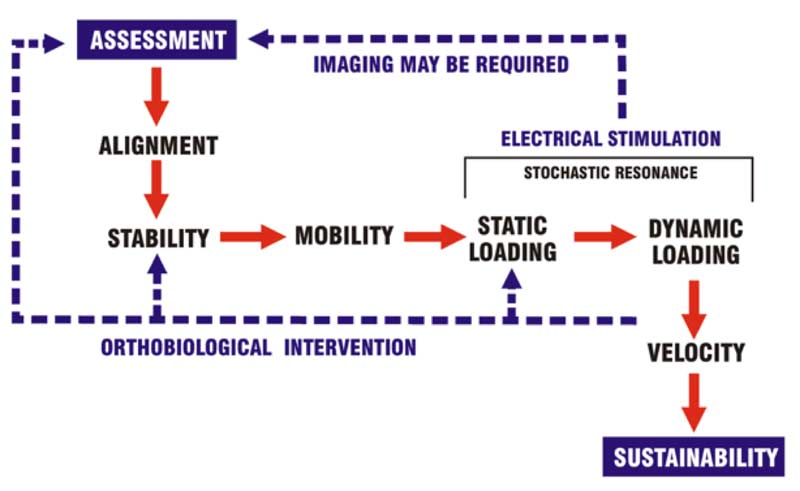

Dean Kotopski, BScPT, RMT, CAc/IMS, MCPA, is the Clinical Director of Performax Health Group in Burnaby, British Columbia. Dean is a 30-year veteran of physical rehabilitation, with certifications in physiotherapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and IMS. Dean began his professional career as an auto mechanic at the age of 18, with a passion for movement and all things mechanical. His enjoyment of athletics and academics soon led him to pursue a career in physical rehabilitation. He has significant experience supporting numerous regenerative therapies including PRP and stem cells of all derivation, and he developed “Force Balance Techniqueä,” a process around physical rehabilitation and orthobiologic support, over the past 10 years. His clients range from general population patients to world-leading professional athletes. For more information on Dean, please visit:

Dean Kotopski, BScPT, RMT, CAc/IMS, MCPA, is the Clinical Director of Performax Health Group in Burnaby, British Columbia. Dean is a 30-year veteran of physical rehabilitation, with certifications in physiotherapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and IMS. Dean began his professional career as an auto mechanic at the age of 18, with a passion for movement and all things mechanical. His enjoyment of athletics and academics soon led him to pursue a career in physical rehabilitation. He has significant experience supporting numerous regenerative therapies including PRP and stem cells of all derivation, and he developed “Force Balance Techniqueä,” a process around physical rehabilitation and orthobiologic support, over the past 10 years. His clients range from general population patients to world-leading professional athletes. For more information on Dean, please visit: