Hip belt squats emphasize the legs with less load on the spine, load the lower body despite any torso or upper limb limitations, and shine in their potential for lower limb hypertrophy. Their recent resurgence has been pushed by strength sport athletes looking for improved leg development, strength coaches who want to load athletes in novel ways, and equipment manufacturers that continue to innovate and abstract with new designs.

Hip belt squats surfaced in the 1970s and have fallen in and out of favor since then, though they’ve always been in the background. According to the story, Louie Simmons invented the device in the mid-70s after injuring his back and was unable to squat. Using some ingenuity, he brought us the belt squat machine that Westside Barbell is known for.

The Soul of Belt Squatting

By removing the load from an athlete’s shoulders and upper trapezius, the hip belt squat places emphasis on the legs with less load on the spine. The removal of axial loading and subsequently lower trunk extension moments let us load the lower body despite any torso or upper limb limitations—hence its original application for powerlifters with blown backs. I’ve used variants with fighters who have injured upper bodies, particularly the shoulders, when even a hands-free safety bar squat caused pain or discomfort.

The hip belt squat also shines in its potential for lower limb hypertrophy. We can train the legs in a high-volume fashion with higher loads without high levels of lumbar fatigue. Anyone who has done high-rep back squats can attest to this. Some of my favorite stories from old-timers are about using belt squats with an exaggerated heel lift to really target deep knee flexion and torch what they describe as lower quads.

Belt squats come in various shapes and sizes, ranging from simple lever arms to weight stack pulley systems. At its most rudimentary, it suspends loads, such as dumbbells or plates, while standing on boxes to provide clearance. Belt squats often are accessory movements used as a plan B option for specific leg development when upper body limitations preclude more conventional squat options; the belt squat represents a vertically oriented task rather than what we commonly see with many leg press options and is a lot less compressive.

Hip belt squats are great for leg development when upper body limitations prevent more conventional squats, says @WSWayland. #BeltSquats Share on XThe belt squat does come with a few downsides, particularly excessive lumbar extension in some athletes—often those who exhibit excessive extension generally—especially if the belt is placed too high. We can sometimes mitigate this by placing the belt just over the hips or by using a harness over the hip belt.

When executing the belt squat, watch for the hips rising faster than the shoulders. An upright object, like a hand support, can help mitigate this, which is why many belt squatters almost instinctively place their hands on their thighs. The belt squat design also influences this. Squatmax-MD, for example, suggests their design—which isn’t fixed like a lever arm—leads to low sheer stress and less gravitation toward lumbar extension.

I recommend avoiding belt squats with beginners or clients who haven’t taken the time to establish solid squat patterns. A precondition for getting the most out of belt squats is to make sure the client’s squat pattern is good. This may seem trite, though I’ve issued the same warning about the hand-supported squat. Novel squat variants may offer a back door to a loaded squat pattern, but the coordination of upper limbs, torso, and lower body is crucial for long term development.

As I said in my post about earning the back squat, “movement quality drives loading strategy and not the other way around,” and we should pay the same respect here. Much like the leg press, belt squats do not provide the same holistic coordinative challenge conventional squats do, so rotate belt squats or use them in a fashion that ensures good competency.

Very little real research has been done aside from a notable 2015 study by Gulick et al. that found similar muscle activation in back squats and belt squats (using a squatmax-MD machine). The study also showed greater activation of quadriceps and less for hip extensors, so belt squats could be very useful for bodybuilders and athletes who already focus on deadlifts, RDLs, and hip thrusts.

Video 1. The pin-style belt squat is popular in part because it’s inexpensive, but it may not be the right fit for all athletes. If an athlete does’t have the leg length or prefers not to go wide, then pin-style options may not work.

Another study on belt squats by Evans et al. (using a Pit Shark) found that a lever arm belt squat machine failed to activate the glutes similarly to the barbell back squat. This runs contrary to what well-known coaches have said, including Travis Mash: “The biggest benefit that I’ve noticed is that it really emphasizes hip extension.” “The way the belt sits, if you don’t activate your glutes you won’t reach extension, so it pretty much turns every single exercise into something that emphasizes the glutes.”

This may be an issue of technical execution regarding coaching, set-up, or the choice of belt squat device. The hip extension contribution, however, is not dissimilar to other squat variations, though the belt squat does have differing knee extension moment arms, hence the increased quad activation. It’s also possible that mileage may vary among belt squat device machines.

Belt Squat Options

Freestanding Belt Squats

Freestanding belt squats are the most rudimentary way to employ the movement. An athlete uses a conventional dip-belt and squats with the load slung between the legs. The issue is usually clearance, so you’ll see individuals do these standing on two boxes or benches so the weight can dip below their feet.

The major limitation to freestanding belt squats is the amount of load that’s practical or comfortable due to set-up and execution issues. It was this limitation that apparently spurred Louie Simmons to build his machine. Dismounting boxes with a heavy weight between the legs isn’t for the faint-hearted. The progression is to use belt squat lever arms or machines.

Belt squat marches and unilateral work, which I’ll discuss later in this post, can’t be performed with this type of set-up because the lateral swing of the load makes its very unstable.

A variant is landmine belt squats which use the landmine’s ad hoc lever attachment. While these can be a pain to set-up, they do offer an alternative. We can get some stability by turning it into a long-levered movement. The landmine allows us to load the movement more substantively than a conventional belt squat.

Another option is to use a single-ended loading pin for belt squats. Again this allows for greater loading, but the width of an Olympic-sized plate dictates stance width, which can be a problem for smaller athletes or when you want to do narrow stance squats.

Video 2. Using a landmine attachment, we can load the belt squat more substantively than we can a freestanding belt squat.

Lever-Based Belt Squats

Lever-based belt squats have become more popular recently due to modular set-ups, allowing them to be attached and unattached from modern rig or rack systems that save space, unlike a belt squat machine. These usually have a fall away catcher that allows the user to set-up, then stand up and perform the movement as the catcher swings away. The catcher then can be replaced and the weight returned to the set-up position.

Video 3. Lever-based belt squats are more popular now due to space-saving set-ups.

Belt Squat Machines

Belt squat machines with under-loaded pulley systems, such as the one popularized by Louie Simmons, have been around for a while. Pit Sharks and similarly designed machines generally take up a similar amount of floor space but are very effective robust lever-based machines.

Design considerations include the relationship between the lever arm, the load, and the athlete’s position. More recent designs place the load much closer to the center of gravity, which correlates much better with straight bar movements. We also increasingly see the addition of handles to make the movement hand-supported. This allows for increased loading and resists the forward pull the belt sometimes places on the athlete under very high loads.

More than Just Squats

Belt Squat Marches

Belt squat marches are another movement coming out of the powerlifting community. The idea is to stand tall in the belt squat while either marching on the spot or with different IR/ER on the unloaded leg. Loading the standing leg in an advantaged position certainly provides feel to the working muscles. These are used mostly as a warm-up or as activation for reps or GPP work for time. After air travel, I’ve used a band variation to stimulate hip flexors and glutes and get my hips feeling normal.

Video 4. The belt squat march, often used as a warm up exercise.

Split Squats and Staggered Belt Squats

It’s also worth considering split squats and staggered belt squats for a novel stimulus; I’m particularly keen on a staggered hand-supported belt squat. The main issues are set-up and comfort, as the variability in set-ups means that a split squat is often not viable but a staggered squat is.

Creativity goes a long way in setting this up. You can find an excellent example using a double harness with a double lever machine in Chris Korfist’s post about the Bulgarian split squat.

Video 5. I especially like the staggered hand-supported belt squat for a novel stimulus.

Belt Squat Romanian Deadlift

The belt squat RDL is another novel variant for the belt squat alone, the addition of dumbbells and kettlebells, and even band-anchored variations. A shift in belt position will create some sheer stress and potential traction in the lower back. This can benefit athletes who experience a lot of compression from conventional heavy barbell work. The RDL is a perfectly viable option as a special exercise or when the conventional RDL isn’t an option.

Video 6. The RDL with dumbbells and hip belt is a creative way to get a new stimulus with athletes. Experiment and see what works for your environment.

Ranged Trimetric Belt Squats

Although these are considered out in left field now, ranged trimetric belt squats are good for rapid contract-relax contexts. I’ve been using them with some of my grappling and MMA athletes to promote rapid contract-relax qualities without the limitation of ankle-based ground force characteristics we need for plyometrics. Because combat athletes spend a lot of time unshod on soft surfaces, their SSC isn’t particularly well developed because their spring ankle complex is not up to snuff.

Ranged trimetric squats usually are performed for contextual timed sets anywhere from 3-10s. I suggest using an underhand grip to allow for upper body contribution and stabilization while the athlete pulls and pushes rapidly in each direction. I file this under looks silly, does good in the category of movements. I have the benefit of owning my own gym, so the athletes aren’t too bothered about looking silly.

Video 7. Ranged trimetric belt squats promote rapid contract-relax qualities without the limitation of ankle-based ground force characteristics.

Integrating Belt Squats into Your Program

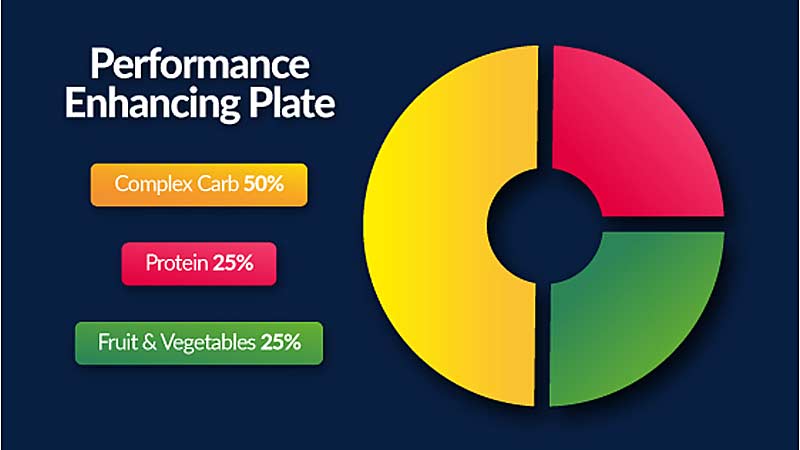

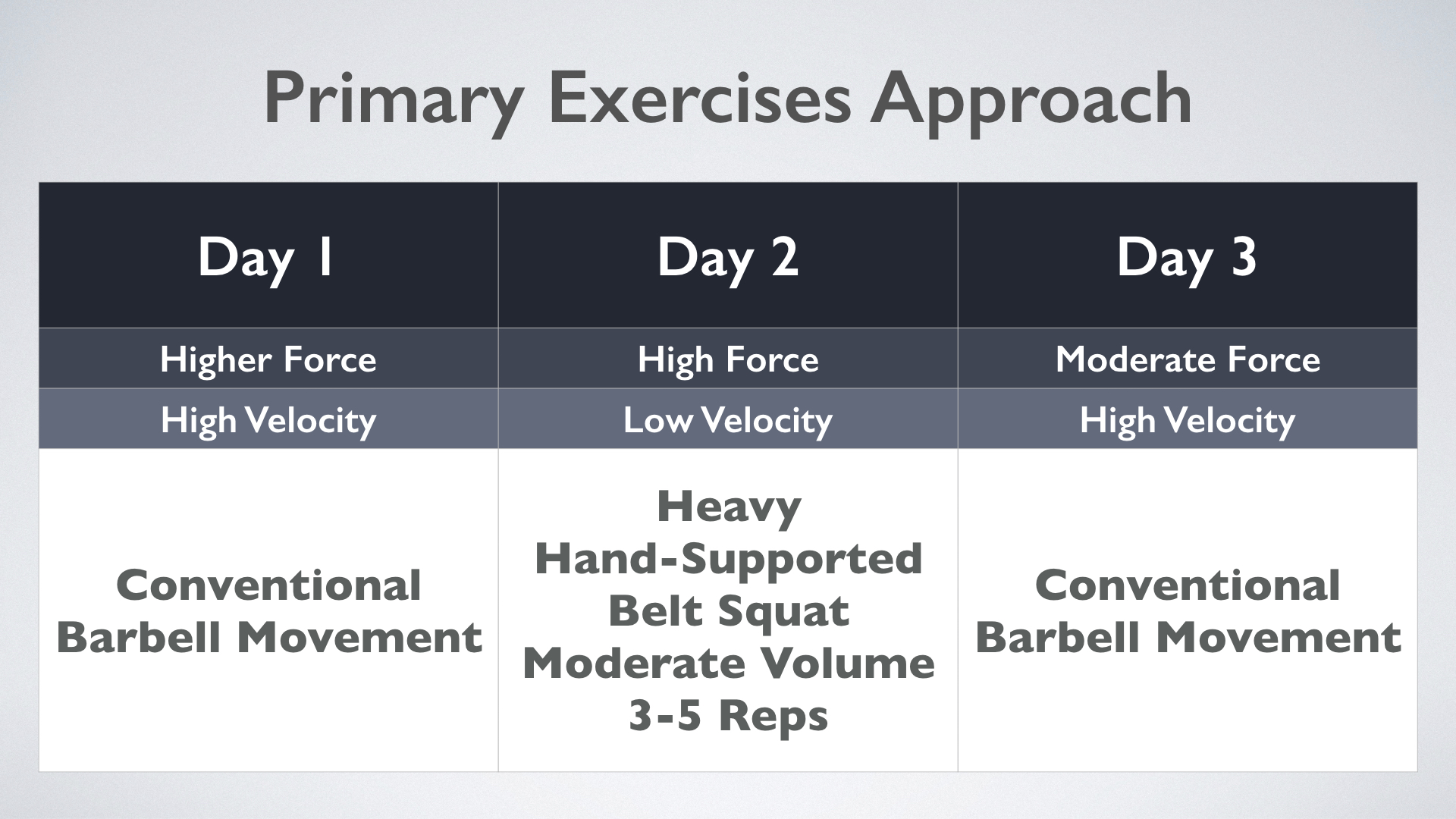

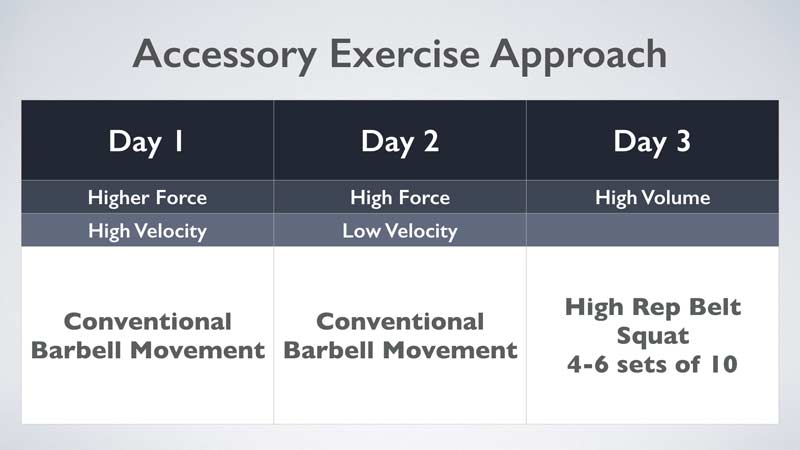

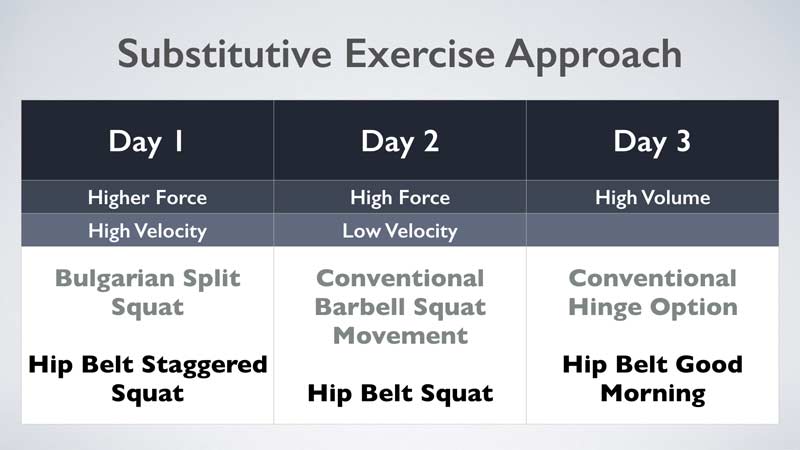

We can look at integrating belt squats in three ways: as a primary force-producing option, as an accessory, or as a substitutive option. Below are some programming suggestions on how to implement belt squatting across a training week.

The primary force-producing exercises make the most of the belt squat’s inherent stability and de-loading of the trunk. They focus very specifically on producing high levels of force under stable positions; variations like hand-supported positions allow for more loading.

Accessory use makes the most of the higher structural stress that belt squatting allows for, so we can train for goals like specific hypertrophy or local fatigue tolerance. I usually place days like this at the end of the week, as the higher volumes at high loads can produce very high soreness levels.

Use the substitutive approach when an athlete presents with a problem that precludes them from using conventional exercises with an axial loading component. This is often a preplanned change or sometimes a reactive substitution performed on the fly. Keeping plan B as close to plan A as possible is a rule of thumb.

Conclusion

Belt squatting offers another way to target lower-body loading and, as with any variant like this, comes with many upsides and a few downsides. While its place is mostly as a supplementary exercise, its value shines in its ability to specifically target the lower body at the expense of some of the systemic stress of conventional lower-body compound movements. When timed correctly, they help maintain peripheral freshness in the upper limbs.

Belt squats shine in targeting the lower body without some of the systemic stress of conventional compound movements, says @WSWayland. #BeltSquats Share on XIts other key use is with athletes who are experiencing something that prevents them from performing conventional barbell training, which was why the belts were used originally. We’ll probably see more equipment innovation going forward, as comfort, space, and expense all come into play when gym owners decide what to put in their facilities.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Additional Reference

English, Nick, “Why the Belt Squat Could be Your Secret to Strength Gains,” BarBend (website), updated January 15, 2018.