Like many of my professional associates and peers throughout the country, over the course of my professional career I have rehabilitated and/or performance enhancement trained the athletes placed in my care. In my four decades of practice, I personally have worked with thousands of athletes participating in many various athletic endeavors. Included in this athletic population are the subset of overhead athletes, such as baseball players, football quarterbacks, track and field throwers, volleyball players, basketball players, tennis players, swimmers, etc. These athletes have competed at the high school, collegiate, Olympic, and professional levels.

With regard to the overhead sport athlete in baseball, football, and basketball, my clientele of athletes, like my other professional peers in the same occupational fields of practice, includes $100,000,000-contract athletes as well as Cy Young award-winning MLB pitchers, NFL quarterbacks, and MLB and NBA all-stars. However, contrary to what many of my professional peers do (as expressed to me via direct conversations with them), I prescribe my athletes specific weighted overhead exercises during their rehabilitation and/or training whenever no valid contraindications are noted.

Contrary to what many of my professional peers do, I prescribe my athletes specific weighted overhead exercises during their rehab and/or training whenever there are no valid contraindications. Share on XSpecifically, with regard to the overhead athlete and the upper extremity, these individuals are rehabilitated, involved in post-rehabilitation return to play, and/or performance enhancement trained for a variety of physical conditions including, but not limited to:

- Non-operative shoulder rehabilitation.

- Non-operative elbow rehabilitation.

- Postoperative shoulder rehabilitation.

- Postoperative elbow rehabilitation.

- Post-rehabilitation return to play and/or athletic performance enhancement training in preparation for their particular sport of participation.

Although it appears that overhead weight training has had a greater acceptance in recent years, conversations of concern still exist with medical professionals, parents, coaches, and, at times, the athlete themselves. During these conversations, I often contemplate the days of Dr. Karl Klein and his support of medical professionals and coaches who condemned the squat exercise, as there was a time where this deep knee bend exercise was considered absolutely detrimental to the ligaments of the knee. This squat exercise concern was proven to be unsubstantiated at least 25 years ago1. These discussions often leave me with the impression that overhead exercise performance is the latest “taboo” in the new millennium.

I mentioned the clientele of outstanding professional athletes to reinforce a point: If specific overhead training exercise were truly detrimental to an athlete’s career, how then could we possibly incorporate them successfully into the physical rehabilitation and performance enhancement training settings? How could they be accepted by these accomplished professional athletes who have so much to lose?

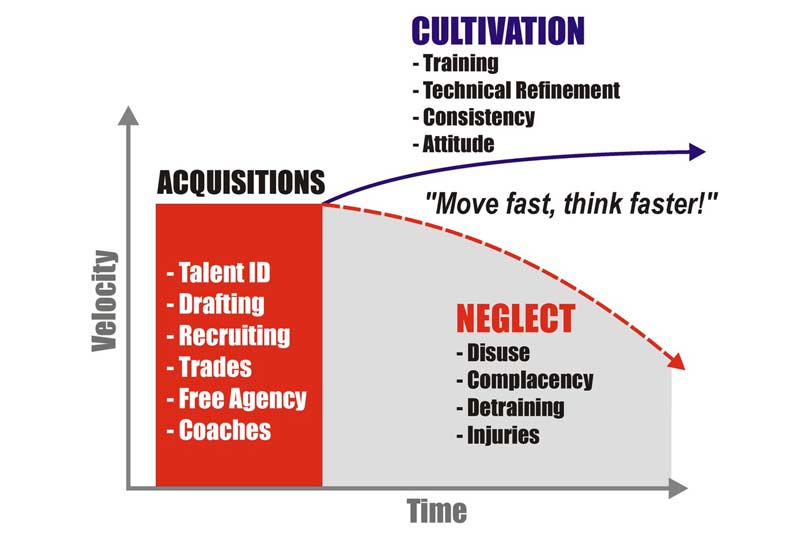

Skill vs. Athleticism

During the course of physical rehabilitation, post-rehabilitation return to play, and the performance enhancement training of athletes, the emphasis is on improving the physical qualities necessary for optimal athletic performance. This achievement assists in optimizing the demonstrated physical skills of the athlete through the transfer of these enhanced physical qualities via the repetitive practice of these physical skills over time. Physical rehabilitation and athletic performance training enhance the athlete’s athleticism.

Unless the rehabilitation specialist and/or strength and conditioning (S&C) professional is also a sport skills coach (i.e., basketball shooting, baseball hitting, baseball pitching, etc.), it is the sport/skill coach who will improve the athlete’s skill level. This article will discuss the rehabilitation, training opportunities, and guidelines for the inclusion of weighted overhead exercises for the overhead athlete.

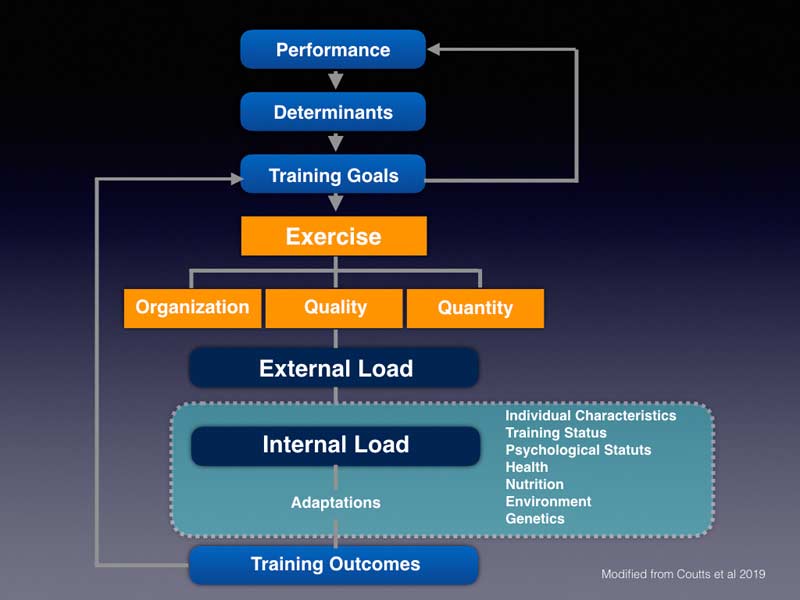

Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development

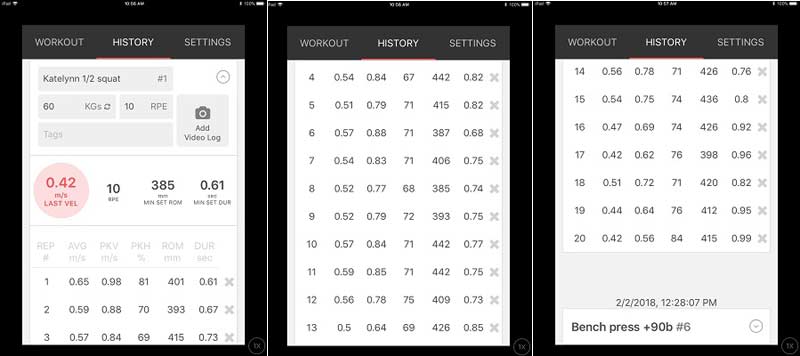

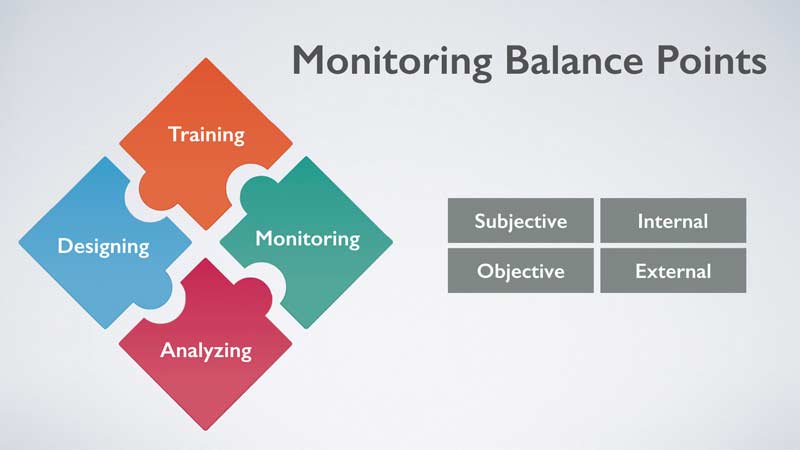

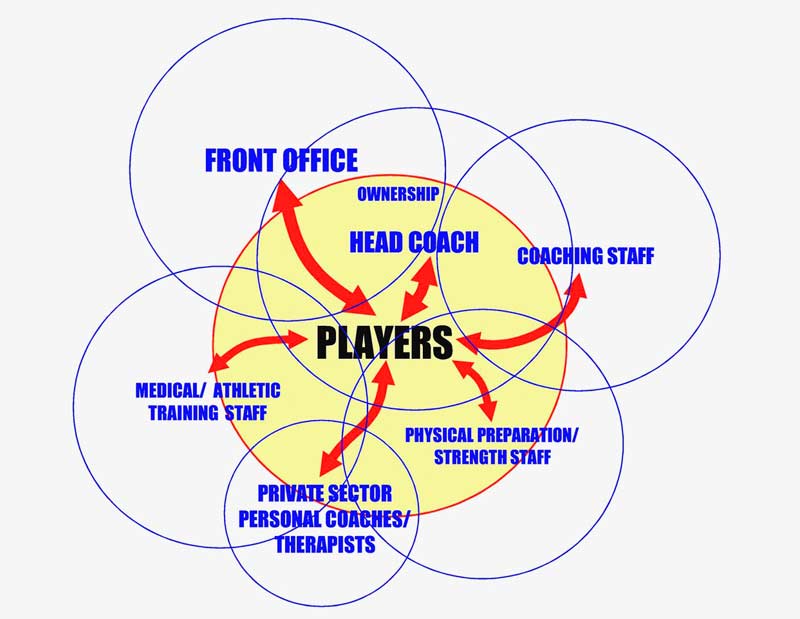

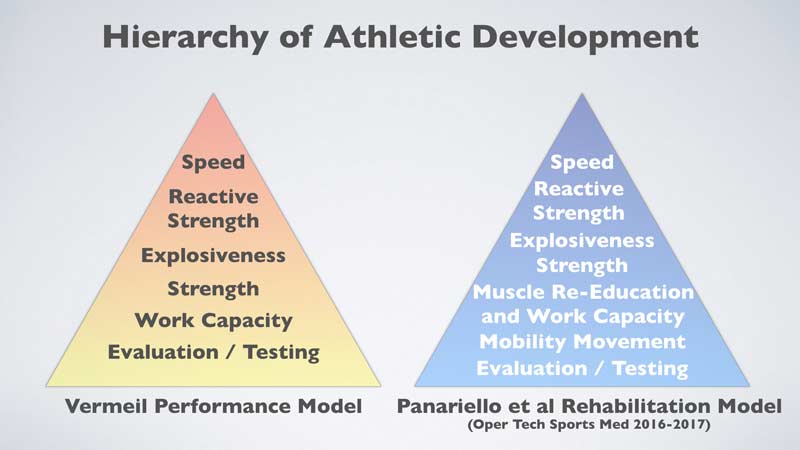

We base our evaluation and programming for the rehabilitation as well as the athletic performance enhancement training of the overhead (or any) athlete upon the philosophy of USA S&C Hall of Fame Coach Al Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development (figure 1).

These training and rehabilitation program philosophies have been described previously in both the literature2,3 and a SimpliFaster blog post; therefore, a thorough review is not required at this time. A recommended self-review of this philosophical system will assist as a guide for the evaluation and testing of an athlete through the development of the diverse physical qualities necessary for optimal physical rehabilitation and post-rehabilitation return to play, as well as ideal athletic performance.

The Kinetic Chain of the Body

For the overhead athlete to achieve ideal levels of performance, it is critical for all muscle and neuromuscular activity of the body to transform from multiple individual segments to a single efficient entity. It has been demonstrated that the best athletes are those who can apply the greatest amount of force into the ground surface area in the shortest period of time4. For this phenomenon to occur, the athlete must establish a strong, stable base of support to maximize the forces initiated from the legs and hips, transfer these forces through the core, and conclude at the shoulder/upper extremity complex to the hand.

The automobile enthusiast may associate this relationship to an engine (i.e., leg and hips), where the forces established are transferred via the transmission (i.e., core) to the steering mechanism (upper extremities and hands) as upper extremity (i.e., baseball) velocity transpires from the ground up5. The kinetic chain of the body also assists to diminish the magnitude of the applied forces in throwing type movements and produce torques that decrease braking forces as a protective mechanism during the arm deceleration phase, the most stressful phase of throwing (overhead) cycle6.

Anxieties of Overhead Exercise Performance

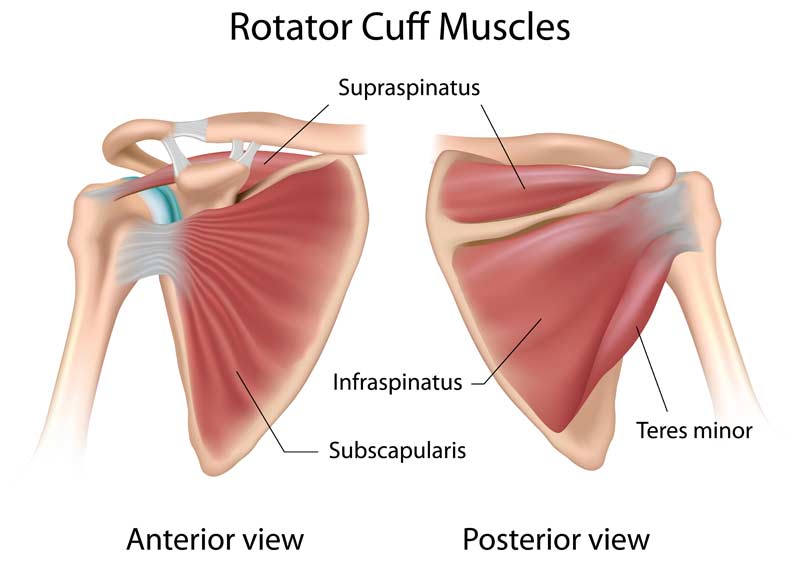

The foremost expressed concern of overhead weighted exercise performance (i.e., the overhead/military press, push press, jerks, etc.) appears to be the potential injury to the rotator cuff musculature of the shoulder complex. The rotator cuff consists of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis (figure 2).

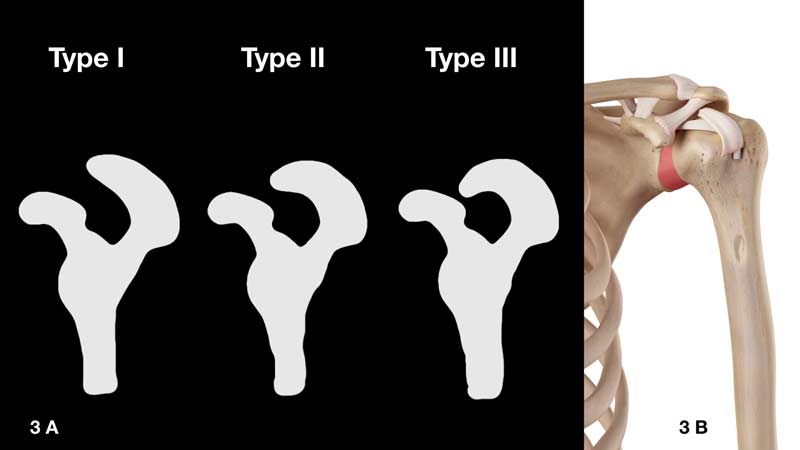

This apprehension is derived from the fear of the possible onset of rotator cuff “impingement” and/or tearing at the underside of the acromion (figure 3a) and/or the coracoacromial ligament/arch (figure 3b). Frequently expressed concerns also include the “dreaded” type III acromion (figure 3a) morphology, which, due to the extended osseous structure, reduces the subacromial space. This space is located between the inferior acromion and the head of the humerus and is approximately 9–10 mm in distance7.

It has been reported that at 0 degrees of arm abduction (arm at the side), the subacromial space is approximately 11 mm, at 90 degrees of upper extremity abduction it is 5.7 mm, and at 120 degrees of abduction it is 4.8 mm8. Investigators have also utilized Fuji contact film to measure pressures per square area on both the acromion and humeral head. With arm abduction performed from 60 degrees to full arm elevation, there was contact between the acromion and humeral head8. Therefore, it was concluded that contact between the acromion and humeral head during this range of elevation is normal.

The physical rehabilitation and S&C professional should take caution with overhead exercise performance in the documented presence of a type III acromion. As it is not financially prudent or even essential to perform diagnostic imaging on every athlete participating in a training program, it is necessary to investigate the scientific evidence to help determine where in the athletic population this specific type III acromion morphology may actually exist.

In a study of 100 Division 1 college athletes (200 shoulders), it was determined that only 2% (four shoulders) exhibited a type III acromion9. In fact, there are a number of medical professionals who believe that the type III acromion likely presents in the later decades of life as a result of the accumulated physical stresses that may result in secondary changes, as occurs with any other aging joint surface. Therefore, it would appear that the concern of subjecting a young athlete to a possible increased risk of rotator cuff pathology due to the presence of a type III acromion is likely overstated.

Prerequisites of Overhead Exercise Performance

Prior to their introduction to formal training program design, the athlete must be prepared to ensure the safety and success of such training participation. Much of this preparation (including overhead exercise performance preparation) would occur during the work capacity phase of Coach Vermeil’s hierarchy. Unfortunately, this stage of training is often omitted in favor of direct participation in the formal training program. Once a work capacity is established, the following are some suggested additional criteria that the athlete should appropriately demonstrate prior to their initiation into a formal overhead training program.

Glenohumeral Scapulothoracic Mobility

The athlete must achieve 180 degrees of arm elevation (figures 4a and 4b), as shoulder flexion deficits of as little as 5 degrees or more have been found to increase upper extremity injury rates in throwers almost threefold10. The greater the deficit in shoulder flexion, the higher the level of stress placed upon the shoulder complex during repetitive overhead exercise performance. Also, 180 degrees of shoulder flexion will support the presence of the appropriate soft tissue compliance, thoracic spine mobility, and scapulohumeral rhythm (to name a few) required for overhead exercise execution. The accomplishment of full shoulder elevation via overhead exercise performance will assist in injury prevention due to the elimination of range of motion deficits, and the acquired full range of motion will be available for the start of the overhead sport’s pre-season and in-season activities.

Scapulohumeral Rhythm Alterations When Lifting a Heavy Load Overhead

There is a normal sequence of movement between the humerus and the scapula during glenohumeral (arm) elevation. The classic work of Inman and colleagues11 has demonstrated a humeral (arm) elevation to a scapulothoracic upward rotation ratio of 2:1 during both sagittal plane flexion and coronal plane abduction between 30 and 170 degrees of motion (arm elevation). However, during dynamic humeral elevation the scapulohumeral rhythm changes, depending upon the phase of elevation and the amount of external load applied to the upper extremity. For heavy loads, this previously described 2:1 ratio changes to approximately 4.5:112. This adjustment in scapulohumeral rhythm is certainly reasonable, as a platform of stability (the scapula) is a prerequisite for the optimal mobility and dexterity of the upper extremity to successfully occur.

The Painful Arc of Motion

An additional concerning overhead exercise topic of discussion with healthcare professionals is the painful arc syndrome. The painful arc syndrome of the shoulder is characterized by pain, usually located at the lateral aspect of the shoulder and upper arm in the area of the subacromial space, the bulk of the deltoid muscle group, and/or its insertion. This shoulder pain may be felt at rest, usually at night, and is typically exacerbated during arm elevation in a specific shoulder arc of motion13. This painful arc of motion usually occurs during shoulder abduction and is situated between 60 and 120 degrees of arm elevation (figure 5).

Shoulder pain that occurs in this range of motion is usually indicative of a disorder of the subacromial region. During discussions of overhead exercise performance, some healthcare professionals have expressed the concern that non-symptomatic athletes exercising through this range of motion may develop the eventual onset of a subacromial shoulder pathology. I have found this concern, with proper preparation of the athlete, to be without substance empirically.

To help alleviate this concern, athletes should initiate all overhead exercises from a racked position of the barbell with the shoulder at 90 degrees of elevation (figure 6). Thus, overhead exercises with a barbell are now only executed through half (90–120 degrees) of this painful arc of motion. Avoidance of a starting racked position (elbow positioned low) still allows for exercise performance but will also include range of motion through the entire painful arc (i.e., 60–120 degrees).

To further address extreme concerns over the painful arc of motion, you may stack boxes (figure 7) to assist in eliminating the eccentric return of the barbell from the concluded overhead exercise in fully extended arm position. From this extended arm position, an athlete may drop the barbell to the extended box height prior to the execution of the next overhead exercise repetition.

However, there are substantial strength enhancements and additional benefits in performing the eccentric phase of the overhead exercise. Whenever appropriate, it is highly recommended to perform this eccentric (lowering) phase in asymptomatic shoulders. Eccentric strength qualities are essential during the deceleration phase of high-velocity overhead activities, as deceleration is the most stressful phase of throwing/overhead type activities.

To best avoid potential concerns with the overhead exercise in the painful arc of motion, it is recommended to: ensure proper shoulder and thoracic spine mobility, strength levels of the rotator cuff, and scapula musculature; perform overhead exercise in the plane of the scapula; and implement an appropriate exercise program design to avoid the onset of excessive fatigue. In my experience, following these guidelines, as well as Coach Vermeil’s hierarchy, resolves any apprehension of exercising through the painful arc of motion and allows for successful overhead exercise performance.

Perform All Overhead Exercises in the Plane of the Scapula

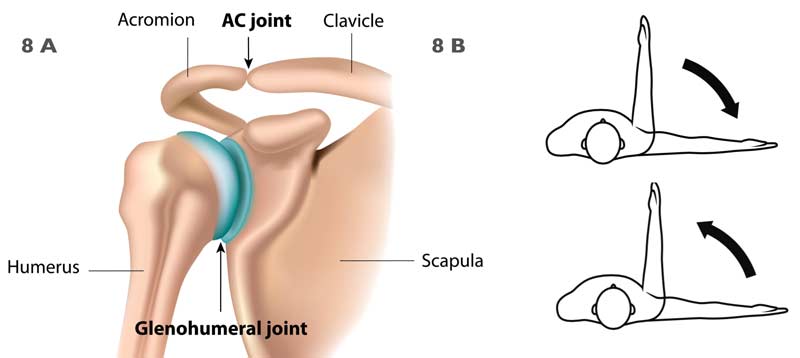

The scapula does not rest on the thorax in a position parallel to the frontal plane of the body. The scapula at rest assumes a position of 30–45 degrees forward from the frontal plane toward the sagittal plane of the body (figures 8a and 8b).

There are many biomechanical and anatomical advantages for performing arm elevation in the scapular plane of the body7,14. Some of these advantages include, but are not limited to:

- The shoulder joint surfaces have greater conformity in this plane of motion.

- During arm elevation, the inferior capsuloligamentous complex and rotator cuff muscles remain untwisted.

- The supraspinatus and deltoid muscle group (rotator cuff-deltoid force couple) are optimally aligned for arm elevation.

- This plane of the body provides for the greatest scapula upward rotation.

- This plane of the body provides for optimal length-tension (force production) of muscles.

As previously noted, scapulohumeral rhythm adjusts from a 2:1 to a 4.5:1 ratio with the application of a heavy load. This change in the ratio implies an adjustment in the elevation and rotation of the scapula, as the application of a heavy load requires a strong platform of stability. Thus, overhead exercise execution in the plane of the scapula will ensure the optimal scapula elevation and rotations necessary to maintain an appropriate subacromial space to assist in prohibiting rotator cuff pathology.

An appropriate hand placement (spacing) on the barbell will ensure this plane of motion is “secured” throughout the overhead exercise performance. It is also important to note that, as the execution of the overhead exercise performance is now performed in the plane of the scapula and not pure shoulder abduction, the concern of the aforementioned painful arc of motion is minimized.

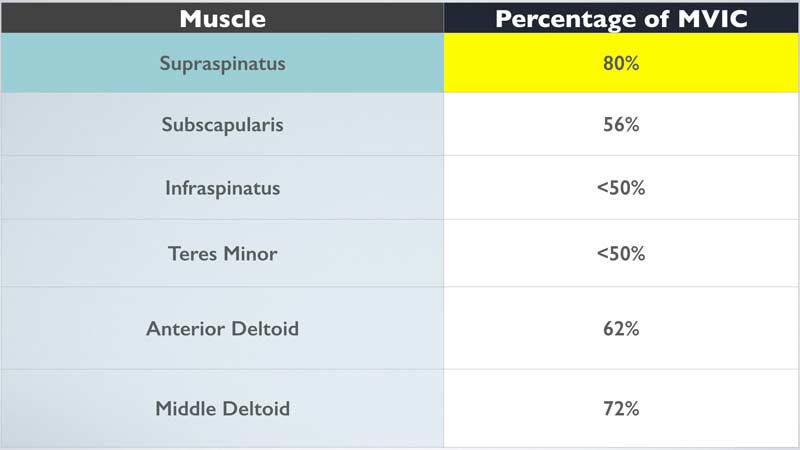

Rotator Cuff Muscle Activity During Overhead Exercise Performance

The execution of such exercises as the standing press, push press, and split jerk take advantage of the benefits of the kinetic chain in the standing position by initiating and transferring forces from the ground up, the same mechanism of force transfer that occurs during competitive sports. The overhead press also exhibits very high supraspinatus muscle activity15, the muscle most often associated with rotator cuff pathology. As a stronger muscle is less susceptible to injury, why would we not want to utilize the same philosophy with the rotator cuff of the shoulder, and more specifically, the supraspinatus muscle? The rotator cuff and deltoid muscle activity that occurs during the overhead press is presented in figure 9.

Also of note, the serratus anterior, a key entity in the serratus anterior-trapezius force couple, is also very active (82%) during the overhead press exercise16. A force couple occurs when separate and distinct muscle groups produce equal forces, creating a rotation by the pulling that occurs in opposite directions. This serratus anterior-trapezius force couple serves several critical functions in overhead activity17, 18:

- Rotates the scapula, maintaining the glenoid surface in an appropriate position for the humeral head.

- Positions the deltoid muscle group to maintain efficient length-tension, ensuring ideal strength, explosive strength, and joint stability.

- Prevents impingement of the subacromial anatomical structures upon the coracoacromial arch.

- Provides a stable base of support, enabling axiohumeral and scapulohumeral muscles to move the arm against an external resistance.

The Effect of Exercise-Induced Fatigue on Shoulder Kinematics

Excessive exercise-induced fatigue can negatively affect shoulder joint kinematics. To comprehend this concept, there must be an appreciation of the rotator cuff-deltoid muscle force couple that occurs at the shoulder. The main function of the rotator cuff muscle group is to counterbalance the forces of the deltoid muscle group and maintain the position of the humeral head centrally in the glenoid fossa (joint) (figure 10b).

Arm elevation in the presence of an excessively fatigued non-pathologic rotator cuff disrupts this force couple, resulting in the same humeral head superior migration that occurs in a shoulder with a rotator cuff tear and/or pathology19(figure 10a). This superior migration of the humeral head may increase the potential for rotator cuff pathology, as the available subacromial arch spacing is now decreased. Additional consequences include increased inferior (downward) migration of the humeral head with the arm resting at the side of the body (figure 10a). Athletes should be cautious when executing overhead (i.e., press) and carrying type (i.e., farmers walk) activities in the presence of an excessively fatigued shoulder muscle complex.

Excessive exercise-induced muscle fatigue may also affect the supporting musculature of the scapula, resulting in decreased scapula posterior tilt, as well as increased scapula protraction, internal rotation, and increased upward rotation. This combined and altered positioning of the scapula, along with the associated superior humeral head migration, serves as an environment for potential rotator cuff pathology.

The establishment of an athlete’s adequate work capacity, as well as the implementation of an appropriate rehabilitation/training program design, is essential to avoid the negative effects of the onset of excessive fatigue of the musculature of the shoulder complex. Excessive muscle fatigue will result in an adverse influence upon the aforementioned shoulder kinematics and can lead to a potentially consequential soft tissue injury.

The Standing Overhead Press

The standing overhead press is a strength exercise that offers many advantages over other upper body strength activities. These advantages include, but are not limited to:

- Potential utilization in both the performance enhancement and physical rehabilitation environments.

- Enhanced strength and hypertrophy of the shoulders and upper extremities.

- Enhanced stability of the lower extremities, hips, and core.

- Execution of exercise in the standing position; thus, forces are transferred from the ground up, as transpires in sport activities.

- The glenohumeral and scapula-thoracic relationship is free-moving without external restrictions.

- The risk of pectorals muscle tears is likely zero.

Activities such as the bench press, incline bench press, and seated overhead press with a bench require the athlete to lie/sit upon this apparatus that includes a backing (figure 11). The bench backing creates a platform whereby the scapulae are “pinned,” so to speak, between the barbell weight, body weight, and bench backing, resulting in compressive forces of the scapulae against the thorax. One of the advantages of closed kinetic chain exercise performance is the stability provided by compressive forces that occur during exercise performance (i.e., the knee joint during the back squat).

Observe caution with regard to the prescribed exercise volume of the bench press, incline bench press, etc. when utilizing a bench backing. Share on XIf the scapulae are compressed and stabilized against the thorax during overhead exercise performance, would there not be a possible adverse disruption to the previously mentioned scapulohumeral rhythm? If the scapulae are “artificially stabilized,” so to speak, due to the described compressive forces during overhead exercise performance, are the scapulae musculature getting a “free ride,” resulting in a decrease in potential strength enhancement when compared to the scapula muscle activity required during standing overhead exercise performance? This is not to state that you should eliminate exercises such as the bench press, incline bench press, etc. from an athlete’s training program design, but observe caution with regard to the prescribed exercise volume in exercises utilizing a bench backing.

The Push Press

As athletes achieve appropriate strength levels with the standing overhead press, a progression for the physical qualities of both lower and upper extremity explosive strength is realized via the incorporation of the push press exercise into the training program design. Although a coordinated contribution of the shoulders, core, and upper extremities is executed during exercise performance, the push press places focus on the lower body. The push press is a knee-dominant activity due to the requirement of maintaining the racked barbell on the anterior deltoids of the shoulders to effectively and efficiently transmit impulse. The exercise has also been shown to produce peak power levels that are similar to the jump squat and mid-thigh power clean exercises20, and it is an exceptional exercise that incorporates the upper extremities to enhance overall explosive strength qualities.

The Split Jerk

It is well-documented that the stride leg plays a critical role in the attainment and maintenance of ball velocity in baseball pitchers21,22. Some of these stride leg advantages include, but are not limited to:

- The landing (stride) leg serves as an anchor, transforming forward and vertical momentum into rotational components.

- Posterior directed landing forces of the landing foot reflect a balance of inertial forces of the body moving forward to create baseball velocity.

- Pitchers with the highest ball velocity also demonstrate higher braking ground reaction forces.

- The ability to “drive” the body over a stabilized stride leg is a characteristic of high-velocity pitchers.

- High-velocity pitchers exhibit greater stride knee extension.

- High-velocity pitchers increase the forward motion of the trunk via stride knee extension during the acceleration phase of pitching.

It is fairly obvious that appropriate stride leg knee extension, stability, and braking abilities have a strong positive correlation to enhancing ball velocity. When reviewing the posture of the stride leg of a baseball pitcher (figure 12a), we see that his stride leg displays a remarkable similarity to the stride leg displayed during the execution of the split jerk exercise (figure 12b).

The split jerk also requires optimal stride leg positioning, stability, and high braking forces while enhancing core and shoulder stability, strength, and explosive strength qualities. The split jerk produces high peak power (i.e., 6923 W) and mean power (i.e., 4321 W) generated forces to transfer through the kinetic chain to the upper extremity22,23.

No Place for Exercise Generalizations

If there is such a pronounced adverse concern by some rehabilitation and S&C professionals to incorporate weighted overhead exercises in the athlete’s program design, why don’t they express this same adverse concern during the execution of overhead activities such as pull-ups, chin-ups, and lat pulldown exercises? Not only do athletes perform these exercises with the arms fully extended overhead, but they execute them with the hands fixed to an exercise bar positioned both overhead and anterior to the midline of the body. Thus, these overhead exercises also include a component of joint distraction forces that potentially position the humeral head more superiorly toward the inferior acromion as well as the coracoacromial arch.

Are we, as professionals, also to believe that the concern with weighted overhead exercise performance is seasonal? Why does there appear to be less concern with the performance of overhead exercises during the off-season training of football quarterbacks versus the off-season training of a baseball pitcher or position player? Many of the athletes trained at our performance center are high school and college athletes who are quarterbacks during the fall sport season and baseball pitchers during the spring sport season. Where is the scientific evidence that documents the vulnerability of the shoulder complex/anatomy due to overhead exercise performance changes depending upon the time of the year?

Why does there appear to be less concern with the performance of overhead exercises during the off-season training of football quarterbacks than of a baseball pitcher or position player? Share on XThis discussion certainly doesn’t imply that overhead exercise “fits all.” Nor does it ever recommend the “cut and paste” method of program design. We should regard and treat each athlete in either the rehabilitation or performance enhancement training setting as an individual based on their own specific medical and training history. That stated, exercise generalizations have no place in either of these professional environments. When appropriate, overhead exercise performance is deemed both suitable and beneficial to include in the program design of an athlete participating in the rehabilitation and performance enhancement training environments.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Panariello RA, Backus SI, Parker JW. “The Effect of the Squat Exercise on Anterior – Posterior Knee Translation in Professional Football Players.” Am J Sports Med. 1994; 22(6): 768–773.

2. Panariello RA, Stump TJ, Cordasco F. “The Lower Extremity Athlete: Post-Rehabilitation Performance and Injury Prevention Training.” Oper Tech Sports Med. 2017; 25(3): 231–240.

3. Panariello RA, Stump TJ, and Maddalone D. “Post-Operative ACL Rehabilitation and Return to Play after ACL Reconstruction.” Oper Tech in Sports Med. 2016; 24(1): 35–44.

4. Weyand PG, Sternlight DB, Bellizzi MJ, et al. “Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements.” J Appl Physiol. 2000; 89: 1991–1999.

5. Hirashima M, Kadota H, Sakurai S, et al. “Sequential muscle activity and its functional role in upper extremity and trunk during overarm throwing.” J Sport Sci. 2002; 20(4): 301–310.

6. Chu SK, Jayabalan P, Kibler B, et al. “The Kinetic Chain Revisited: New Concepts on Throwing Mechanics and Injury.” PM&R. 2016; 8(35): S69–S77.

7. Novotny JE, Woolley CT, Nichols CE 3rd, et al. “In vivo technique to quantify the internal-external rotation kinematics of the human glenohumeral joint.” J Orthop Res. 2000; 18: 190–194.

8. Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, et al. “Articular geometry of the glenohumeral joint.” Clin Orthop, 1992; (285): 181–190.

9. Speer KP, Osbahr DC, Montella BJ, et al. “Acromial morphotype in the young asymptomatic athletic shoulder.” J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001; 10(5): 434–437.

10. Wilk KE, Macrina LC, Fleisig GS, et al. “Deficits in glenohumeral passive range of motion increase risk of elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers: a prospective study.” Am J Sports Med. 2014; 42(9): 2075–2081.

11. Inman V, Saunder J, Abbot L. “Observations of the function of the shoulder joint.” J Bone Joint Surg, 1944; 26:1.

12. McQuade KJ, Smidt GL. “Dynamic scapulohumeral rhythm: The effects of an external resistance during elevation of the arm in the scapula plane.” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 1998; 27: 125–133.

13. Kessel L, Watson M. “The Painful Arc Syndrome: Clinical Classification as a Guide to Management.” J Bone Joint Surg. 1977; 59-B(2): 166–172.

14. Johnson T. “The movements of the shoulder joint. A Plea for the use of the ‘Plane of the Scapula’ as the plane of reference in movements occurring in the humero-scapular joint.” 1937; Br J Surg 25:252.

15. Townsend H, Jobe FW, Pink M, et al. “Electromyographic analysis of the glenohumeral muscles during a baseball rehabilitation program.” Am J Sport Med, 1991; 19(3): 264–272.

16. Moseley JB Jr, Jobe FW, Pink M, et al. “EMG analysis of the scapular muscles during a shoulder rehabilitation program.” Am J Sports Med, 1992; 20(2): 128–134.

17. Kelly M, Clark W. Orthopedic Therapy of the Shoulder. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, 1995.

18. Abboud JA, Soslowsky LJ. “Interplay of the static and dynamic restraints in glenohumeral instability.” Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002; (400): 48–57.

19. Chen SK, Simonian PT, Wickiewicz, TL, et al. “Radiographic evaluation of glenohumeral kinematics: A muscle fatigue model.” J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999; 8(1): 49–52.

20. Comfort P, Mundy PD, Graham-Smith P, et al. “Comparison of peak power output during exercises with similar lower limb kinematics.” J of Trainology. 2016; 5: 1–5.

21. Kageyama M, Sugiyama T, Takai Y, et al. “Kinematic and Kinetic Profiles of Trunk and Lower Limbs during Baseball Pitching in Collegiate Pitchers.” J Sports Sci Med. 2014; 13(4): 742–750.

22. Campbell BM, Stodden DF, Nixon, MK. “Lower Extremity Muscle Activation During Baseball Pitching.” J Strength Cond Res. 2010; 24(4): 964–971.

23. Garhammer J. “Power production by Olympic Weightlifters.” Med Sci Sports Exer. 1980; (12)1: 54–60.