Like numerous strength coaches across the country, I have a front row seat to the year-round sports specialization saga. Regardless of our professional setting—private sector, high school, or club—we all have eyebrow-raising stories our athletes have passed along about another coach, or about situations we’ve witnessed in person. In my current role as a high school strength coach, I have my own deep collection—but one experience in particular stands out.

Two years ago, my women’s soccer team made it back to the playoffs, which is always momentous. I remember my head coach telling me some of the girls would be late to our game because they had a club tournament that night as well.

“Excuse me…what?”

Sure enough, our playoff game was well underway when I glanced over my shoulder and saw those girls sprinting through the parking lot, their soccer bags flailing behind them, cleats in their hands. They’d already played a full soccer game and were potentially about to enter another, with high-stakes and playoff intensity. That scene in its entirety has cemented in my mind the picture of specialization, and a picture really is worth a thousand words.

The playoff game is merely circumstantial, this example is meant to illustrate the mindset and demands of year-round specialization, which regardless of sport or age is the norm for millions of youth athletes. Specialization is just part and parcel of modern-day coaching, for all parties, at all levels. While it poses some barriers and requires a fluid process, it should not exclude the consistent practice of sound weight training.

While it poses some barriers and requires a fluid process, year-round specialization should not exclude the consistent practice of sound weight training, says @rachelkh2. Share on XI often receive questions from coaches trying to figure out the best training plan for their specialized athletes, and I’m met with varying degrees of frustration and indecision. Naturally, the reality is somewhere in the middle. That realistic middle ground can be covered by General Physical Preparation—or GPP—and lots of it.

Defining General Physical Preparation

For those unfamiliar with the terminology, according to Siff and Verkhoshansky: “The GPP is intended to provide balanced physical conditioning in endurance, strength, speed, flexibility and other basic factors of fitness, whereas the SPP (Specialized Physical Preparation) concentrates on exercises which are more specific to the particular sport.”

Note: If you read Bompa and Haff, it’s general physical training, or GPT, but for consistency we will stay with GPP.

Bompa specifically emphasizes the importance of GPP with young athletes because it provides the basis for future training and the capacity to tolerate training—the latter being especially important for specialized athletes. He writes:

“Exercises for general physical development are nonspecific exercises that contribute to the athlete’s physical development. These exercises develop strength, flexibility, mobility, aerobic fitness, and anaerobic capacity. Exercises for general physical development lay the foundation for further training by improving basic motor qualities that are central components of a multilateral program.”

Keyword takeaways from both definitions: balanced, basic, nonspecific, development, foundation. Music to any strength coach’s ears (well, most anyway).

Needless to say, specialized athletes will particularly benefit from GPP, given their chronic exposure to everything *except* balanced and nonspecific training, says @rachelkh2. Share on XCommonly, we see GPP utilized in the early off-season as a welcome reset, both physically and mentally, following the intensity and grind of in-season. If I use my volleyball athletes as an example, their high school and club seasons combined can span upwards of 48 weeks a year. Needless to say, specialized athletes will particularly benefit from GPP, given their chronic exposure to everything except balanced and nonspecific training.

GPP Framework

GPP training is highly simplistic, or should be. Along with numerous others, I was inspired by Dan John’s five basic human movements, and developed my own list based on my preferences and the athletes I train. Everything we do, including GPP, is inclusive of the following seven patterns:

- Squat

- Lunge

- Hinge

- Knee-dominant hamstring

- Upper push

- Upper pull

- Core: anti-extension, anti-rotation, anti-flexion

GPP provides a way to successfully manage the stress of the high school and club seasons, while simultaneously contributing to development, as it provides practical and realistic solutions to the unique needs of this population, for four primary reasons that I outline below.

1. Training is Training

With two competitive seasons, endless practice sessions, and many other unknown variables, there is likely little capacity to recover from intensive or neurologically demanding weight room sessions. I emphasize *likely* because without the resources or tools to monitor stress, I cannot say definitively that more intensive training isn’t possible. However, based on the information I can assimilate, the risk of causing harm is not worth the attempt.

This is not a reason to refrain from load or to retreat from training. We must view all training as stress with the potential to either help or hurt, rather than have a myopic view that a session must contain X, Y, and Z exercises. Should we always endeavor to include ground-based, multi-joint movements that can be traced back to the basic patterns? Yes. But the mechanism of load or the classification of an exercise as a regression does not take away from value, or more importantly, that it is stress.

We must view all training as stress with the potential to either help or hurt, rather than have a myopic view that a session *must* contain X, Y, and Z exercises, says @rachelkh2. Share on XThe training goals of specialized athletes who play the same sport year-round are not necessarily going to mirror those of athletes following a traditional model of one succinct competitive season (like football). In other words, weight room training should be focused on ways to keep the athletes healthy enough to play year-round. With this population, maximizing the basic fundamentals in various ways still contributes to development and health.

GPP is training. Goblet squatting is training. Dumbbell snatching is training. Training is training.

2. Variability Improves Ability

Thousands of hours in ankle braces, thousands of repetitions of the same movement, and thousands of hours in stagnant postures. If they aren’t part of a comprehensive strength and conditioning program, most athletes probably aren’t moving outside of their sport.

This creates two extremes on a movement continuum. When they are moving, it’s confined to practice and games; when they’re not, they’re sitting in class all day or hunched over a screen. Both chronic extremes, with little or no variation.

This is where GPP and a qualified strength coach can help athletes become better, more coordinated movers through movement variability in the weight room. Variability doesn’t mean novelty for the sake of novelty. Variability should be recognizable as modifications of the basic movements listed above. Variability reflects itself in what I term modifiers, some of which I list below:

- Stance: split, b-stance, kneeling, half kneeling, tall kneeling

- Plane of motion: frontal, sagittal, transverse

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Offset position or weight

- Mechanism of load: landmine, med ball, dumbbell, etc.

One of my favorite tools to use in GPP training is the landmine, because of its versatility and ability to challenge and improve coordination. For taller athletes, it can be especially beneficial to help increase body awareness and control with their longer limbs. I like implementing it in many ways, but specifically as a unilateral press in a half-kneeling stance because it improves several things simultaneously, including:

- Global stabilization, including anti-extension and rotation of the core

- Coordination

- Scapular upward rotation

- Upper body pressing strength

Another example—and more recent addition to my exercise bank—is the split stance RDL. I’ve implemented these with my volleyball team, and although they’ve previously mastered bilateral hinging, this movement was unfamiliar. So, coaching the athletes to own this new position was a learning experience for all. Changing the context of a pattern should not be complicated. I like using a split stance simply because it builds on previous mastery, helping to form a more competent mover. Additional reasons I like to use a split stance:

- Lower leg stability

- Balance is not a limiting factor for weight as opposed to a single leg RDL

- Unilateral strength and size development for posterior chain

The short answer for getting athletes to move better is to get them moving! GPP provides a platform to expose and load joints in new ways, which helps correct movement restrictions and improve motor learning. While prioritizing safety and transferability, there are numerous ways to modify the basics in order to create variability and improve overall movement ability (some of which you can see HERE).

GPP provides a platform to expose and load joints in new ways, which helps correct movement restrictions and improve motor learning, says @rachelkh2. Share on X3. Develops Athleticism

Heavily researched and heavily debated, early specialization (or participation in a single sport before puberty), can begin as young as seven years of age. A study in 2017 by Buckley et al. showed the average age a current high school student began specializing was 12.7 ± years old. So, by the time they reach high school, kids who specialize have been doing so since middle school, or before. If they go on to play collegiately, some will have been playing one sport, year-round for a third of their life.

Specialization is the quintessential representation of the expression “run before you walk.” Developing a base of general movement proficiency, although contradictory to the premise of specialization, is advantageous for athletes in numerous ways.

In his book Range, author David Epstein elaborates on the importance of breadth and how some of the most successful people, including athletes, did not begin with a narrowed or specialized focus: “Breadth of training predicts breadth of transfer. The more contexts in which something is learned, the more the learner creates abstract models, and the less they rely on any particular example. Learners become better at applying their knowledge to a situation they’ve never seen before, which is the essence of creativity.”

Simply put, the more diverse scenarios an athlete can experience, the better. Unfortunately, by the time they reach high school, it can be difficult—although not impossible—for specialized athletes to pick up another sport. This is where the role of a strength coach and the weight room become invaluable for athletic development.

Returning to volleyball as an example, during GPP, most of the athletes’ power work is done with med balls in the transverse plane. Teaching them how to express power in non-specific helps them become better athletes first, then better volleyball players. We also work simplified sprint mechanics for the same reason.

When athletes learn to demonstrate new and unfamiliar movements with proficiency, it also builds confidence—and that may be the most valuable asset a strength coach can cultivate, says @rachelkh2. Share on XOne population that often gets forgotten about and lost in the fray of team sports are distance runners. Although the structure of their competition is different, the hours they spend in the same posture and the high rep nature of their sport very much fits them in the “specialized” category. For distance runners, getting in the weight room is perhaps the single best thing that can be done to improve performance. One of the ways I aim to develop their athleticism (and yes, it helps runners to be athletic) is by prescribing unilateral and bilateral jumps in the transverse and frontal planes. Learning to express power and develop stability in these unfamiliar planes builds their athleticism, making them more efficient runners.

My goal in using GPP to build athleticism is to help athletes not look like fish out of water while performing any unfamiliar task at hand. When they learn to demonstrate new and unfamiliar movements with proficiency, it also builds confidence—and that may be the most valuable asset a strength coach can cultivate.

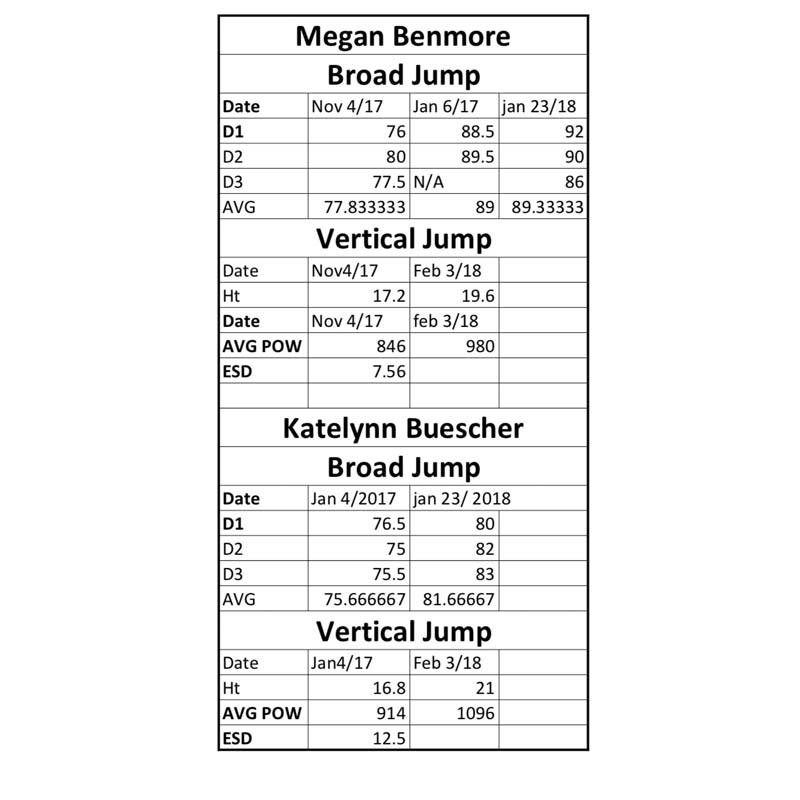

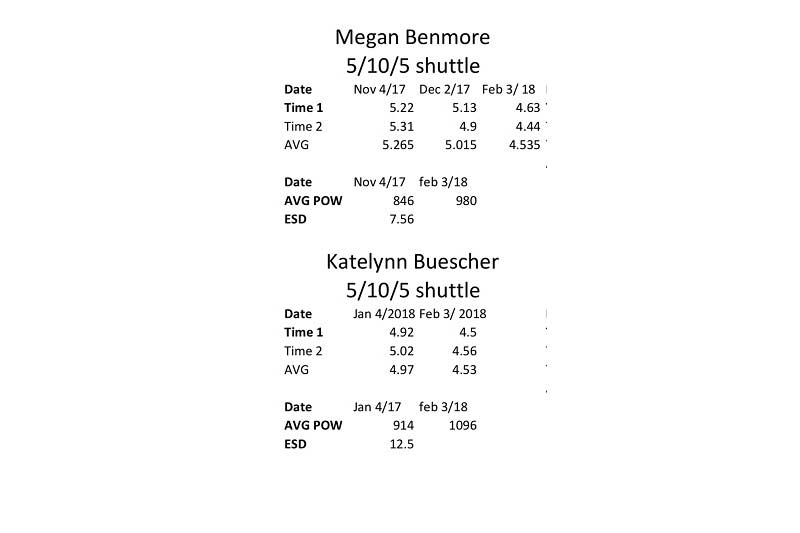

4. Increases Performance

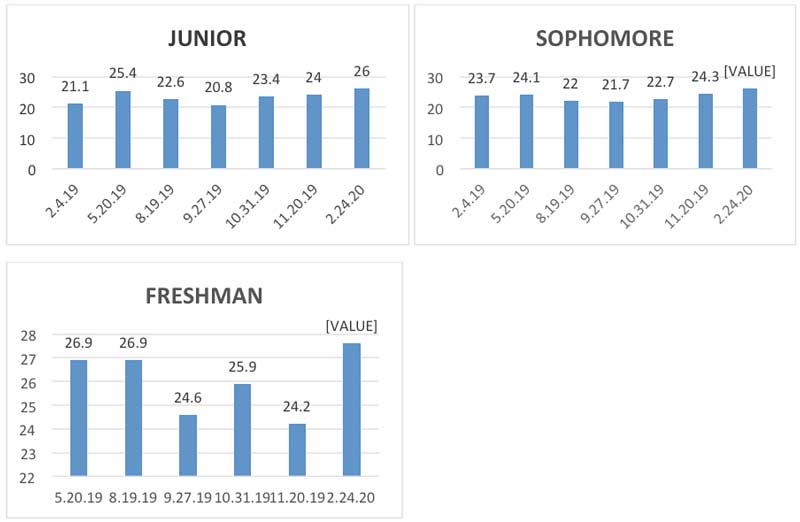

It’s possible to observe performance gains with GPP. With young athletes, performance gains can be recorded using the bare minimum due to their training ages—I get it. But when working with specialized athletes, if you’re keeping track of practice hours and competition (and you should be), performance metrics are hardly, if ever, a priority.

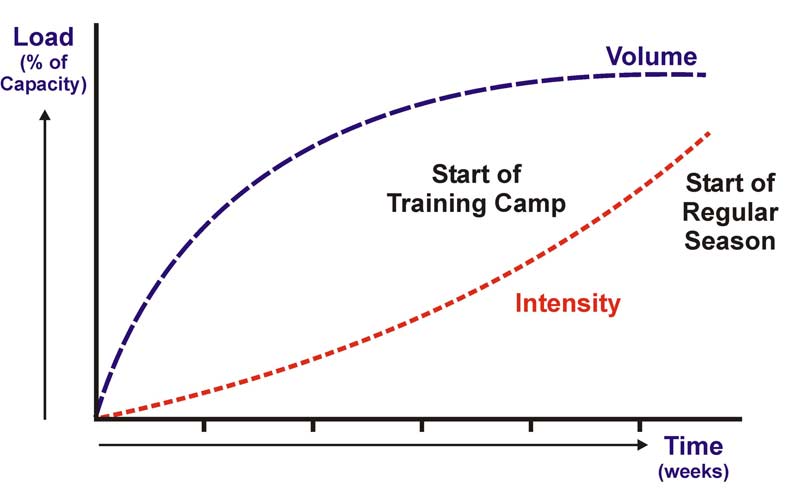

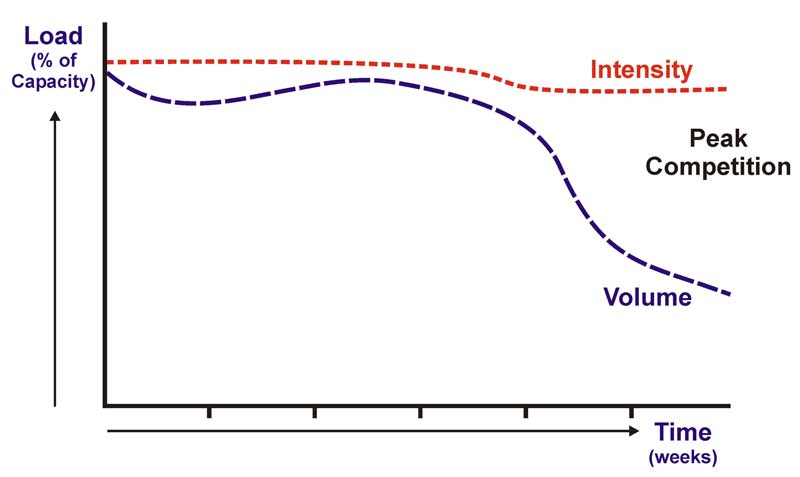

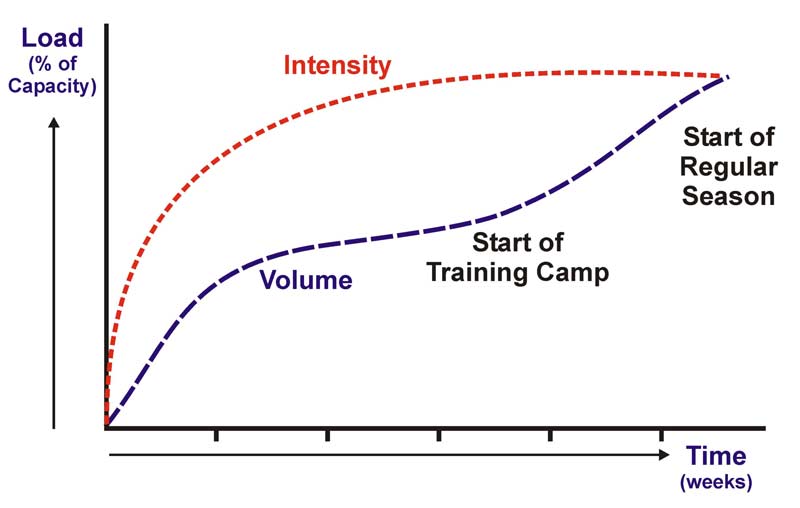

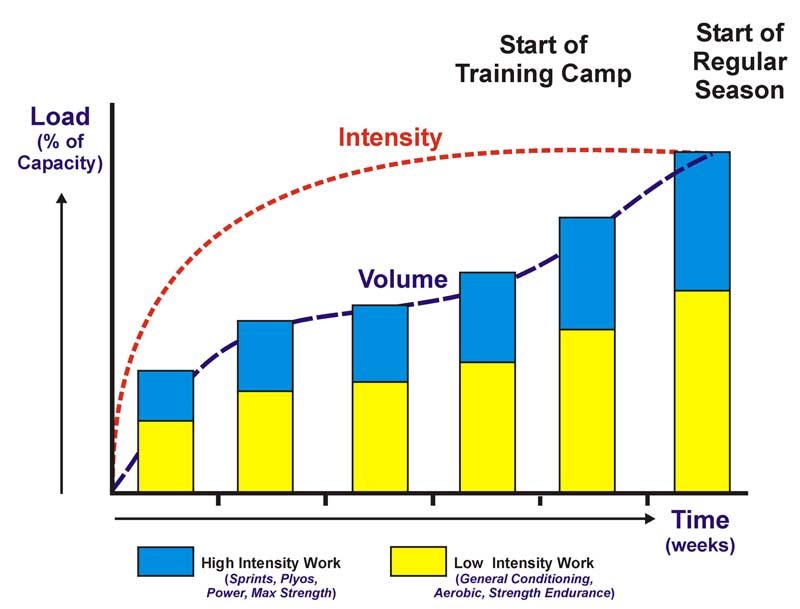

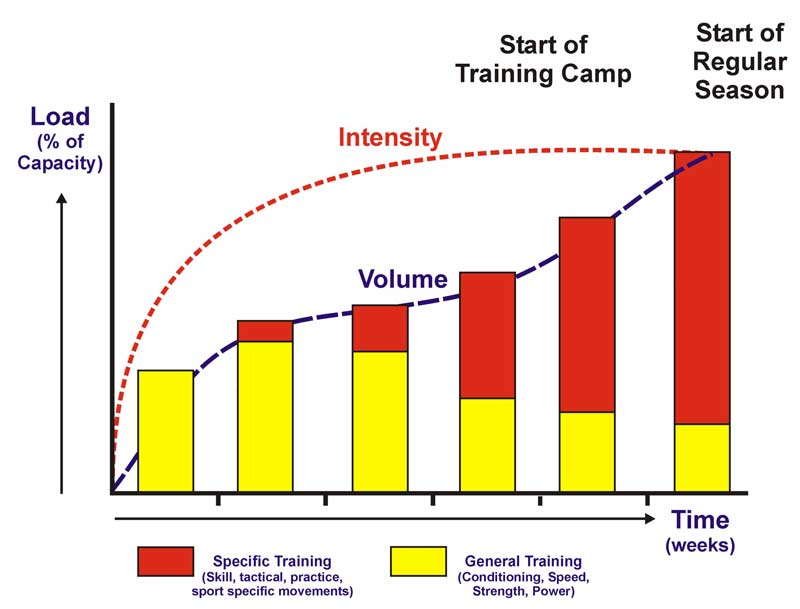

GPP is commonly prescribed in higher volumes and moderate intensities, but I scale it back to moderate volume and moderate-to-low intensities in efforts to prevent soreness and overtraining. This enables them to safely continue lifting while competing for their club teams. The goal is to keep their training stimulus a trickle rather than a stream, allowing them to recover and continue improving.

Would these graphs indicate greater improvements if I could get them under heavier weight during club season? I’m positive the answer is yes. But as far as I’m concerned, healthy athletes with a bonus of consistent progress is a win.

Implementation in Your Sport

As the title suggests, specialized athletes need GPP, and lots of it. How much is a lot? That’s dependent on a host of factors unique to each program.

My volleyball team spends anywhere from 7-10 weeks in a GPP phase at the end of the high school season, which then spans well into half their club season. Truthfully, we could probably do it longer and continue to see benefits. It comes down to knowing your athletes, their needs, and the direction of your program.

For those reading who aren’t strength coaches, GPP will not only be highly beneficial for all your athletes, it’s also a simpler way to develop your weight room coaching skills, as much of GPP is less technical than many of the traditional barbell movements. This is not to say GPP requires less coaching. Every movement in the weight room—whether highly technical or regressed—should be coached with equal fervor and attention.

I hope this has shed some light on training specialized athletes. By no means is GPP a replacement for getting under a heavy bar, but when utilized and coached meticulously, it has the potential to help your athletes while preparing them for more intensive training down the road.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Bompa, T. and Haff, G.G. (2009) Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training (5th ed.) Human Kinetics

Brenner, J.S. and COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS (2016) “Sports Specialization and Intensive Training in Young Athletes.”Pediatrics, 138.(3).

Buckley, P.S. et al (2017) “Early Single Sport Specialization: A Survey of 3090 High School, Collegiate, and Professional Athletes.”Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, Jul 5.(7),

Epstein, D (2019) Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. Riverhead Books

Verkhoshansky, Y. and Siff, M.C. (2009) Supertraining (6th ed.) Verkhoshanksy