[mashshare]

Early specialization, club ball, the year-round athlete—one precipitates another. When these topics arise, conversation among the collective sports medicine community, high school coaches, and especially strength coaches skids into grumbles, complaints, concerns, and misconceptions. Unfortunately, no matter how many big names in the sports world state their condemnation or how many conclusive articles spell out the dangers, society refuses to look back.

This is not to say that we, as strength coaches, should cease educating or voicing our platforms for long-term athletic development (LTAD)—or generalizing before specializing—but specialization is the reality for millions of kids. Those of us who work with these single-sport athletes have an obligation to help them through careful attention and thoughtful action.

Specialization is the reality for millions of kids. Those of us who work with them have an obligation to help them through careful attention and thoughtful action, says @rachelkh2. Share on XWorking closely with these groups, as I and many of you do (seven of my eight teams, including track, compete year-round), is as much a niche as coaches who train collegiate, professional, or tactical athletes. I’m a full-time strength coach at a 6A high school in Denton, Texas. My role is uncommon (unfortunately) across the country, but the frustration of working with year-round sports is widespread.

For the purpose of this article, I refer to volleyball to demonstrate my points, but I intend for the following concepts to be applied to other year-round sports (e.g. baseball, soccer, basketball).

So, How Do You Train Year-Round Athletes?

To some of you, what I’m about to describe will sound very similar, but to others, this may be a new perspective: 100% of my current varsity volleyball team plays club. The high school season spans 12–13 weeks from August to early November, depending on their postseason run. Light to moderate club practice begins after Thanksgiving and tournament play starts in January, ending in late June, totaling anywhere from either 34–36 weeks or 46–49 weeks.

This is just practice and play, not the extra workouts or private lessons these kids likely undergo. More on that later.

If you train or work with year-round athletes, or any population for that matter, your job is to leave them better than you found them. But how do you add to the betterment of an athlete when there is scarcely room to add anything?

My insights are not the final word, but I think you’ll find that applying and expanding the following concepts will help optimize the training time you do have with year-round athletes:

- “Undo” volleyball all year long

- Individualize training when necessary

- Train strength consistently

- Less is more

‘Undo’ Volleyball

A lot of what we do as strength coaches, regardless of level, is reverse the consequences of repetitive movements and overuse of year-round athletes. For volleyball athletes, the hours they spend in ankle braces, the volume of swings and serves they do, and the travel time spent bunched up in planes and cars would be staggering if totaled. Again, the specific nuances of this can be applied broadly.

A lot of what we do as strength coaches, regardless of level, is reverse the consequences of repetitive movement and overuse of year-round athletes, says @rachelkh2. Share on X“Undoing” the chronic wear and tear that their bodies endure takes a permanent front seat in my program. I do this by devoting time specifically to the following areas on a weekly or daily basis:

- Feet and ankles

- Hips

- Soft tissue

- Shoulders

Feet and Ankles

In my opinion, the feet and ankles are the unsung heroes of athletic performance and more than deserve their due consideration. Stiff, immobile ankles cause a cascade of problems, and for volleyball players, knee pain appears to be the most prevalent.

Warm-ups, whether in the weight room or before practice, are done barefoot in order to “free” the foot. Not only does this strengthen the bottom of the feet and ankles, it improves range of motion in plantar and dorsiflexion and excites the sensory feedback loop from the feet to the brain. Isolated ankle mobility is addressed through band distractions or the knee-to-wall exercise before lift, or it is sometimes paired with a primary movement.

Hips

Keeping the hips mobile is crucial for a plethora of reasons, including knee health, and is something we also address on a daily basis by squatting deep in warm-ups, typically in a sumo stance. Of course, we also practice flexibility and mobility in isolated areas like the adductors, glutes, and hip flexors, but sitting deep into the hips every day is the simplest, most effective way to keep them healthy.

Soft Tissue

I’m fortunate to work with a head coach who prioritizes the physical well-being of our volleyball athletes by frequently putting her own program agenda on the back burner. The program purchased enough 18-inch foam rolls for each athlete to check out and keep throughout the year.

Once per week, the team does soft tissue stations addressing common problem areas including the TFL, quads, glutes, calves (also improves ankle mobility), QL, lats, and adductors. Lacrosse balls are used for traps, pecs, neck, and rotator cuff, and I frequently include a station for active isolated stretching (AIS) for calves, quads, and pecs. The volleyball coaches implement this on non-lift days after skill work for 20–30 minutes.

At the beginning of each season, I do an education session on the foam roll and AIS stretching to reacquaint athletes with how to target different areas and how it translates to performance. Having their own foam roll and understanding how to use it encourages them to use it when at home or travelling.

Getting your head coach to buy in or allot this time must start with your athletes. Female athletes, in particular, are looking for a connection or bond, whether you’re their coach, athletic trainer, or strength coach. Sitting down with them and educating them on how to foam roll and stretch is a great way to initiate this. Not only does this build a bond of trust, it provides them with tangible feedback because they can physically feel what you’re teaching them. And although this is done as a team session, it becomes individualized because sensory feedback is unique.

Shoulders

Keeping the shoulders healthy comes down to balance and consistency, as overhead and front-sided shoulder volume with volleyball athletes is exorbitant. Restoring and maintaining thoracic spine extension and rotation is paramount for shoulder health and can be accomplished several ways.

I employ ground-based movements weekly, whether as part of warm-up or as fillers between primary lifts. Supporting body weight on the hand(s), balancing, or maneuvering the body around the hand(s) is an effective way to improve the mobility and stability of the shoulder and thoracic spine.

Some of the movements I utilize are downward dogs, sit-throughs, and bear crawls, as well as some traditional movements like deadbugs with floor slides, thoracic extension on a foam roll, and quadruped variations. Upper body pulls and rowing movements are prescribed every lift; most commonly, we use TRX straps or bands for face pulls in high volume (2–3 x 10–15) and chest-supported or 3-point rows for strength (3–4 x 5–8).

Video 1. Athletes can do remedial work that acts as a great warm-up and mobility solution. Sit-throughs can be modified and programmed in countless ways.

Individualize Training

As I mentioned earlier, practice and play volume is not the only thing to account for when working with year-round athletes. A group of my volleyball athletes play for the same club; a club that contracts a strength coach. Additionally, it is not uncommon for club coaches to put them through “conditioning” workouts or strength workouts of their own every week. Private lessons that include jumping, swinging, and serving may also take place, sometimes prior to a three- to four-hour practice. The amount of time on their feet, impacts incurred, and volume of overhead work would be startling if it was audited.

Consequently, communication is imperative—before you add to the pot, you must know what else has been poured in. The old saying, “too many cooks spoil the broth,” is true, but when working with year-round athletes, too many cooks will poison the broth unless someone takes the time to simply ask some questions and then make a decision based on what is best for that athlete at that time.

Too many cooks will poison the broth unless someone takes the time to simply ask some questions and then make a decision based on what is best for that athlete at that time. Share on XWhat does individualized training look like in real time? While I half-heartedly applaud the clubs and coaches for making an effort to include strength, it often falls short of the mark. For those kids who lift at club on Monday nights, it means there is no bandwidth to squat on Tuesday mornings with me. I wish it was an exaggeration to say these kids were subjected to high-volume (5×8 some days or 5×10 others) back squatting (and no, not with just the bar) for four months straight. There is perhaps a time and place where this protocol might serve a purpose, but all things considered, it’s far from an ideal prescription.

How do I know they are telling the truth? Because I’ve built relationships with each athlete, which goes back to communication and trust. Forcing them to front squat with me simply because that is what is programmed is not in their best interest. Instead, they do some posterior chain work like RDLs or band pull-throughs and additional sets of accessory work like chest-supported rows or suitcase carries.

Sports coaches often have the outlook that individualism has no place in a team setting, and while that view is needed for a variety of reasons, the extent of that philosophy can have varying breadth depending on the population you train—among other things. For collegiate programs, stricter adherence to that view is easier to enforce because all members and athletes are unified under the same team, with fewer outside variables (like club workouts) to contend with.

When it comes to culture, everyone should be on the same page, but when it comes to the health and well-being of an athlete, making individual adjustments to workouts is a minor detail in a much bigger picture. Making decisions based on what is best for the athlete is your job as a coach, anyway.

Train Strength Consistently

Most athletic endeavors take place on the bottom right of the force-velocity curve, where high impact forces are also incurred from stops, breaking, changes of direction, and landing. Year-round athletes spend double the time in this zone, which makes training on the opposite end even more prudent.

Year-round athletes spend double the time in the bottom right zone of the force-velocity curve, which makes training on the opposite end even more prudent, says @rachelkh2. Share on XConsistently spending time in the weight room and performing movements that require high force development (squats, hinge variations, chin-ups, upper body pressing movements) helps balance the curve by providing better shock absorbency, which leads to fewer injuries and nagging pains in the long term.

Getting strong and staying strong is akin to insurance for any athlete. The nuances, opinions, and standards of “What is strong?” make for a valid discussion but are not the focus of this article. Squatting 1.5–2x body weight is commendable, but difficult to accomplish with year-round athletes for numerous reasons. Focusing weight room time in the pursuit of a metric leaves other important qualities on the table, and can set you and your athletes up for failure.

Ideologies and dogmatic notions about training have no place at the table regardless of population, but especially with year-round athletes. This is not to say you can’t employ your preferred method (I like 5/3/1), but knowing when and being flexible is key for your success.

Training athletes who play year-round is not the setting for stubbornly adhering to a program simply out of the fervent belief that said program is gospel or because so-and-so does it over at X university. The question, “What is best for the athlete?” should drive every single decision regarding training. Not, “What method is going to boost their squat numbers the fastest?” or “We’re squatting 85% today because that’s what is programmed.”

One of the many great things about working with youth and high school athletes is their ability to get stronger simply through maturation. It is also important to remember that strength gains still occur even when training with submaximal weights.

The bottom line is that you are lifting consistently rather than obsessing about what exercises you’re using or how much is on the bar. That said, straying too far from squats, lunge variations, hinging, upper body pushes and pulls, and carries is not advisable.

It happens often that we’re in the middle of a strength cycle, but a regressed pattern like goblet squats will be better for the athlete(s) on that particular day than heavy front squats. Sometimes this allows me some freedom to shift the focus of the lift to the upper body movement, typically by including more sets. It can be frustrating in these scenarios because although you know developing strength is crucial to the health of the athlete, it cannot come at the expense of their health. Training strength consistently matters more than the exercise, method, or program.

On days where pulling is the emphasis, we commonly perform concentric-only deadlifts or rack pulls. The eccentric stress is dosed into exercises like Nordic curls, glute-bridge walkouts, and chin-up variations.

Less Is More

As a rule, in strength and conditioning, sports performance, human performance—whatever you call it—the minimum effective dose is the recommended dose. Again, this is dependent on a host of factors, but those are not the point of this article. Conceptually, less is more can be applied to more than just volume—intensity, duration, frequency, or mode also apply.

As mentioned, seven of my eight teams, including volleyball, lift twice per week, year-round. Volleyball lifts Tuesday and Thursday during club season and Wednesday and Saturday during high school season.

Would three times be ideal? Yes, but we aren’t training kids in an ideal world to begin with. Twice per week, year-round, is sufficient because they are in season year-round.

Additionally, attendance is a factor because, during club season, Friday is a travel day, and many athletes are en route to tournaments. Routinely, for those who are present, Fridays are designated work capacity days that include low- or zero-impact movements like slide-board, spin bikes, and suitcase carries.

Not all my kids have the situation where they lift at club, but they do share in the fact that they are playing (jumping) extreme volumes on the weekends from January to June. When they play in convention centers around the country, it is not uncommon for them to be on concrete, which takes an unforgiving toll on their bodies.

Blasphemous as it may seem, I rarely program jumping. There is a small window from the middle of November until mid-December that I squeeze in some basic single leg hops, emphasizing control and landing. Once high school preseason begins, I program low-volume jumps as part of post-activation potentiation work (PAP) for about three weeks, then negate all jumping when high school season starts.

Again, in an ideal world, it would be prudent to train more jumping, but given the volume of jumping they already do, there is no room left in the bucket, nor is it necessary. I’ve found that by simply getting stronger, jump performance and landing capacity can and will improve without including it as part of training.

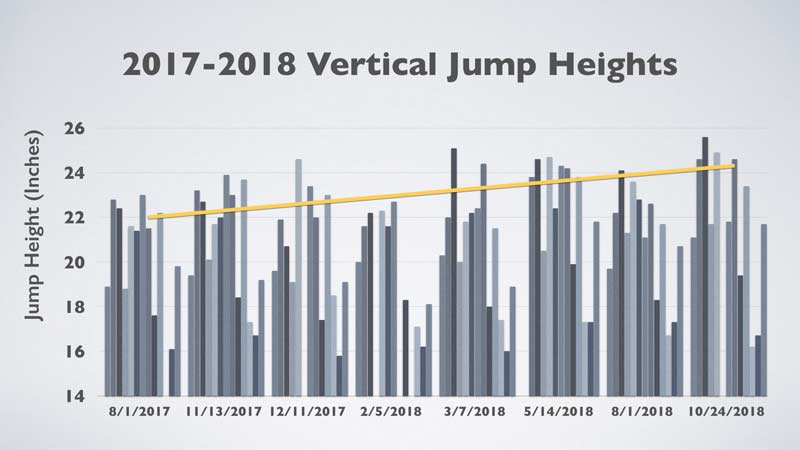

I’ve found that by simply getting stronger, jump performance and landing capacity can and will improve without including it as part of training, says @rachelkh2. Share on XI test verticals every 1–2 months with the Just Jump System. The chart below shows athletes’ verticals at the beginning of the 2017 season until the end of the 2018 season. The peaks occur in May after we complete our max strength work, before summer adjournment when club intensifies and lifts are less consistent. Then they peak again in October at the beginning of post-season. Both peaks occur when strength training has occurred consistently, and again, the only jumping is what is done at practice or in games.

Lastly, I teach the hang clean, and we use it and its various derivatives throughout the year. However, if I had to choose one tool for implementing explosive movements, it would be dumbbells. Not only are dumbbell snatches, cleans, and jerks easier to teach and more forgiving on the body, but they allow you to train unilaterally. For year-round athletes, restoring and maintaining balance is critical for health and longevity. Minimize input to maximize output.

Small Drops in the Bucket Add up

Training or working with athletes who play year-round can be a daunting task, but rather than focusing solely on the problems of year-round athletics, focus your attention on how you can help these athletes without overfilling the bucket. Fight for their health, fight for the need for a qualified strength coach in every high school, and fight for generalization before specialization. It is a tireless task that may be slow to yield comprehensive results, but prioritizing your athletes’ health will not go un-thanked, least of all by them.

Rather than focusing solely on the problems of year-round athletes, focus your attention on how you can help these athletes without overfilling their bucket, says @rachelkh2. Share on XYou may only be able to add small droplets at a time rather than a continuous stream, but as the saying goes, “More is not better, better is better.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]