Chances are, you’re already using biofeedback and don’t know it. Or like most coaches, you’re familiar with it enough to do something proactive but not enough to feel like you’ve reached its full potential. We believe in using technology, but only enough to make a difference, not so much that we feel dependent on it or it slows us down (although sometimes this is unavoidable). In our experience, athletes love technology and we value data. But we don’t want it to get out of control and turn into another selfie experience.

In the last two years, we’ve invested heavily in technology to get more information on our athletes so we can design better workouts and improve our results. We learned that technology that provides a measurement has helped us tremendously. Each passing week and season, we get a little more versed in its role and its shortcomings. Trends don’t always dictate action, but when science and experience link up, it’s hard to ignore.

Differences Between Biofeedback and General Feedback

Perfectly defining biofeedback is not easy, and the things we’re doing with biofeedback only scratch the surface. I’m not even sure everything we label biofeedback qualifies as such but, for now, it’s close enough. A good definition for biofeedback is included in the article “Biofeedback for Sport and Performance Enhancement.” Although I recommend reading the article, I’ll save you the exploratory search and include the definition here:

“Biofeedback training is a technique of gaining control of self-regulation, based on information or feedback received from the athletes’ body and mind.”

When you hear the term biofeedback, most coaches think about relaxation drills to lower heart rate or hooking up an athlete’s brain to help them discover how to get into the zone. Honestly, we don’t teach many sport psychology methods for relaxation at our facility, but we’ve used stress monitoring for years with heart rate variability apps. We should not stigmatize biofeedback as a way to teach athletes how to deal with nerves. We should see it as a method to connect the real world to what athletes experience internally.

#Biofeedback connects the real world to what athletes experience internally, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance Share on XThere’s a difference, however, between helping a minimally-trained athlete understand their body and using biofeedback to pull the last bit of performance out of a well-trained elite athlete. Using technology and common sense to monitor and manipulate an athlete’s program constantly (relax, it doesn’t have to be changed every day because of a bad HRV score or jump performance) takes experience using the technology and a lot of time to understand the data and what it’s telling you. But it’s application is invaluable.

We’re not trying to redefine biofeedback, but when we add a direct measurement, good training has the potential to be great training. While coaches have always used feedback from their eyes, direct measurements cut the middleman out of the equation. It doesn’t hurt our ego if an athlete is independent. We should be nudging them forward and not hand-holding all the time. At our facility, you’ll see Sean and me coaching—you’ll also see independent training when an athlete is properly educated.

General feedback is any information given to the athlete while biofeedback comes from a specific measurement added to the mix. General feedback is important, but without measurement it’s limited. We do both, and the results are far better than they would be if we excluded either one.

Barbell Tracking: Getting the Most of Every Rep

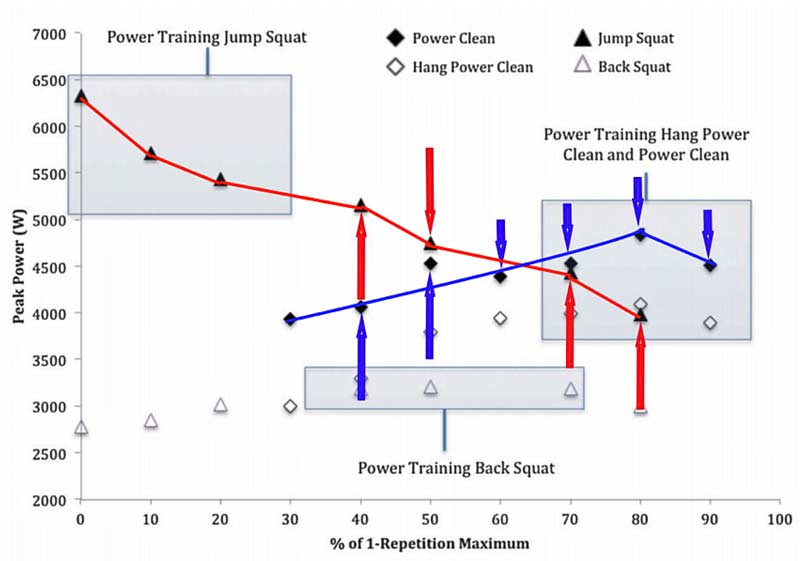

Don’t worry, we won’t bore you by rehashing the same ideas that are in just about every velocity based training (VBT) article released. We want to make a point about taking the next step rather than simply copying the latest fad. Plenty of research and coaching blogs talk about bar speed and getting athletes better just by showing them their velocity readings. Using velocity feedback helps, but why not crank it up a notch and consider barbell tracking as a whole?

Biofeedback on distance and bar path could be just as valuable to coaches and athletes. Arguably, a beginner athlete might not need to focus on velocity when they’re not sure how to set up their feet, but a tool that provides more information about depth and bar path could prove very beneficial for engraining a pattern. Although it’s not always about more information, when is the right information ever wrong?

Video 1. Coaches care about three goals during lifts, which become very simple when the loads become heavy. Having an athlete maintain technique, effort, and awareness of fatigue is everything when working with large groups.

Just the other day, a research article on feedback using GymAware was pushed on social media, promoting the idea that giving the athlete more information increases their power when training. I like that. Although you shouldn’t need a piece of technology to tell you when to pull a kid back and polish up technique, you can easily display such information to the athlete using the right tool. We love autoregulation and have plenty of ready-to-go templates for athletes who earned their right to self-select (some of) their programming. Using a GymAware keeps everyone honest, including the coaches.

We care about accountability—making an athlete value the disciplined lifting requirements that differentiate an athlete who is just doing a workout from the athlete mastering their training. In the short run, using GymAware makes an athlete compete and instantly aware of what they’re doing. In the long run, with back-end reporting, we see the little differences that show they achieved the desired result.

Biofeedback isn’t only for the athlete to get higher wattage. It also lets the coach see if the athlete is adhering to the instructional side of training and how coachable they are. We’ve used the GymAware system for a while now and realize it’s not new, but we’ve seen trust foster when an athlete knows what we say matches up with what the device’s readings.

Digital Pacing and Conditioning with LED Rabbit

If you’ve ever been tested in a group setting or competed in race events, you’ll know a lot about pacing. Biofeedback with pacing works. Instead of showing an athlete what they can do, the feedback helps an athlete become aware of how fast they should go. Pacing with technology is chasing a ghost you can never beat, but you’re not truly competing with a machine.

Instead of showing athletes what they can do, #biofeedback helps them become aware of how fast they should go, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance Share on XIn our experience, a percentage of athletes fail conditioning tests due to their ignorance and a lack of understanding about the pace needed to pass. With the LED Rabbit, we now have a way to add instant visual feedback as an athlete learns and practices pacing. Nothing is wrong with an old school stopwatch and whistle, but making an athlete feel like they’re in a video game beats them sitting on a couch all day.

LED Rabbit offers instant visual feedback to help athletes learn and practice pacing, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance #biofeedback Share on XAt the gym, we joke about how athletes will start calling shuttle tests the light test instead of the beep test in a few years. The basic timed beep is biofeedback, but adding LED lights moves a program from medieval to high tech. The solution is literally “flashy,” but don’t confuse engaging for entertaining. Light pacing systems are perhaps one of the best ways to connect athletes to what they’re doing when implemented properly.

Track and performance coaches will be most intrigued by the light system. Having pacing lights for long sprints (400m) and endurance work requires a curb to have LED lighting, but you can do so much more. Performance coaches can use the LED Rabbit to set and keep athletes on pace. Conditioning tests are the most difficult to sell to athletes, but nearly any team coach worth their salt wants to know if the athletes are just as fit as they are fast. And besides, although disheartening to some extent, it’s easier to sell a coach and team on fitness rather than speed.

Video 2. Pacing shuttle tests with smart LED systems will not be the trend—it will be the future as the research supports the approach. Adding pacing improves the workout, as better data is not just about accuracy, it’s about knowing how an athlete can push themselves.

We have some great ideas for the future, such as using the LED Rabbit as a coaching tool. While we trust our eyes and have video, having a light system for an athlete is like a metronome for a musician. We’ve barely even started with light-pacing and other technologies and plan to watch this space as it grows and matures. After one trial, the value was obvious. And we expect creative coaches to find a way to make this even more useful and effective in the next few months.

EMG: Are Your Muscles Firing?

Everyone in this profession has heard an athlete or fellow coach ask about a muscle not firing properly. If someone knows or feels that a muscle is not functioning, then let’s stop the guesswork and see for ourselves. If you don’t trust the research and are suspicious of the information shared by the lab coats, try getting your hands on electromyography (EMG) equipment and experiment for yourself.

#EMG #biofeedback is fantastic for experimenting with exercises when research isn't available, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance Share on XWe are no strangers to EMG but don’t use it often and don’t claim to be scientists. We do have access to equipment that we could use for lab experiments, but as coaches we care about simple and easy wins. In our experience, EMG is strictly for research and simple biofeedback; it’s not a perfect monitoring tool yet. For something to be used as an everyday monitoring tool, it must check a few boxes:

- Simple set up and implementation

- Quick feedback and easy to interpret data

- Group-friendly

EMG isn’t going to solve every problem, but we’re huge fans of getting your hands on a device and experimenting with a few exercises “to get to the bottom of things,” pun intended, with all the glute activation hype.

Exercise selection and EMG are tied together a little too much, but where there’s smoke, there’s sometimes fire. Enough science behind EMG tells us that it’s acceptable to trust the measurements from experiments. The only problem is that not every exercise is researched, especially with machines and movements that are less common.

Here at Exceed, this is our second year using Athos. We just got the second generation product, and clearly they’ve upgraded the shirt and pants. Coaches who are engaged enough to purchase an EMG system are probably smart enough to know the difference between in-the-trenches use and a formal research study. Watching a screen change colors is not coaching and certainly not science. When you have a specific purpose, however, EMG feedback is fantastic.

Video 3. Knowing when muscle activity is absent is just as valuable as knowing when the muscle contracts. Using wearable EMG to assess a movement’s effectiveness is an established practice, but real-time feedback is just as exciting.

Early return to play is the area we expect to see the product working well for us in the future. An injured athlete is desperate for answers and is a far more willing participant with wearable technology. From working with athletes in the past, we’ve also learned they can have trust issues and sometimes feel betrayed by their bodies. EMG can reduce issues athletes have with confidence by showing that they can get their injured muscles working as well as the muscles that help reduce injuries. Right and left symmetry is tricky and requires analysis on the back end with the portal, but with early stage rehab, the app is straightforward enough.

Heart Rate Monitoring: What’s Old Is New Again

It’s true, heart rate monitoring is old news. Some coaches have chosen not to worry about it and have gone “organic,” trusting an athlete’s ability to listen to their body. Other coaches are like lab technicians and spend enormous amounts of time hooking up gear to their athletes looking for a magic number to crack the code. Don’t be in a tribe or camp that’s polarizing. Don’t be obsessed with heart rate data or ignorant of the research. Heart rate data helps model performance and recovery and is one of the most well-established ways to monitor training.

Directly providing feedback to athletes has been done with cycling mounts and wrist watches. These are great options for endurance athletes, but what about rowing circuits or tempo runs over longer distances? Mounting flat screens or even small displays isn’t a real solution for everyone. A more connected solution is smart glasses. The Google Glass attempt failed to hit the mainstream, and the ReconJet product line died, but we’re hoping that the Solos product pans out.

Instantaneous heart rate is very useful for conditioning, showing an athlete the actual work they’re producing rather than the “perception deception” that often occurs on days where they may be a little tired and experience unrealistic indications of fatigue. Though smart glasses aren’t for everyone, they’re likely to become more common, so it’s best to prepare for them.

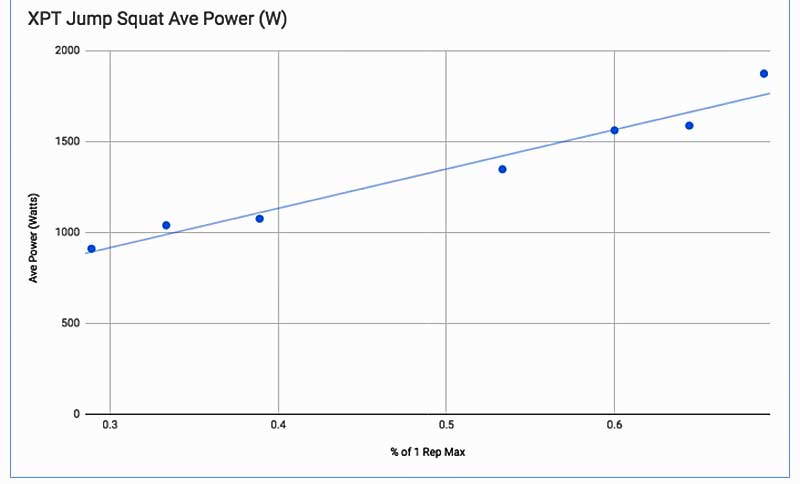

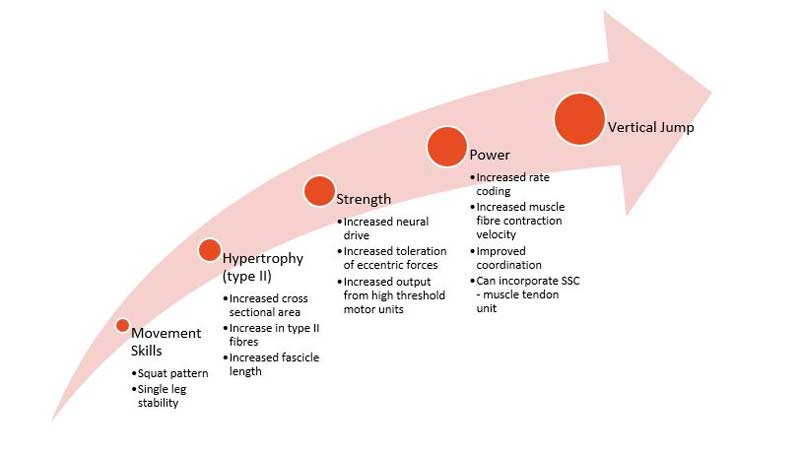

Jumping and Speed Performance: Adding Intelligence to Effort

Last is the most obvious way to gauge effort and improvement, providing feedback for jumping and sprinting. It’s useful to know how fast an athlete is or how well they jump out or up. The two questions coaches must consider are whether they want to test athletes frequently and whether they want to enter the realm of training with velocity and distance. The technology to do both exists, but the bandwidth for coaches working with groups in real time is challenging and may not be for everyone.

Biofeedback doesn’t need to occur in every session. In fact, running on full throttle all the time can burn out an athlete. It’s not necessary to always use adrenaline for the dirty work—and it’s a little reckless in our book. Sprinting, while far more complex, is actually easier to manage than jumping.

While IMUs are viable and marketed as a jumping solution, they only estimate performance and don’t provide an accurate way to monitor jumping in the wild. In an isolated test, sure you can test an athlete, but coaches want to see information in real time with high accuracy. What is the solution? Know how much information is enough to get better, not to feed a curiosity addiction.

There’s a lot of excitement over flying sprints or short sprints, but what about the work between high-intensity training days? From middle school to pros, we see what happens when you gaslight everything all the time. The cost of sprinting on the body is enormous, so sprinting fast without chasing personal records is a responsibility we bear for our athletes in the long run.

Knowing an athlete's best current performance & what relative #speeds they respond to is everything, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance #biofeedback Share on XUsing speeds between all-out and barely stimulatory is about 10%, so the margin of error is wide for coaches to get results without sprinting all-out. Athletes have different responses to effort: some improve technique, some maintain it, and of course, some fall apart. Knowing an athlete’s best current performance and what relative speeds they respond to is everything.

Although it takes longer and requires more work, programming speed and timing is only the starting point. True, arousal and adrenaline help, but so do rest and recovery. Timing is not only about bringing the best out of an athlete for one session but also knowing how to “release the hounds” properly for the whole season. Timing and monitoring are extremely helpful as feedback tools because, as many coaches know, our 70% and their 70% and their friends’ 70% are often vastly different.

Video 4. Force analysis is great for planning, but simple measures like height are valuable as well. It doesn’t matter which testing system you use for immediate feedback, though deeper analysis does require more information than contact mats provide.

At our facility, we have a considerable number of athletes who roll through each day. It wouldn’t benefit them, or even be possible for that matter, to test and monitor them using all of our technology everyday. Depending on the time of year, we treat them on a case by case basis, at least in a global view, considering the level of athlete, the frequency of their training, and sometimes just for the hell of it.

We test some athletes as a monitoring tool. Some of them train using technology to ensure effort and purpose. And others train and test periodically just to ensure they’re “trending” positively. There are many ways to use jump and sprint testing as biofeedback tools. There is no if, just how you want to do it.

Don’t Only Keep it Simple, Keep it Transparent

There are plenty of other options, including video feedback (which we swear by), but that would take an entire article to cover fully. We wanted to show how simple additions of the appropriate technology could improve a workout. Technology doesn’t make your job obsolete; it makes you more effective and more productive. If you add one piece of technology to training to help with feedback, you’ll start to see the results pile up. Don’t forget that feedback includes human interaction, as honest reminders of effort and timely compliments can mean everything to an athlete. Let the sports technology do the monkey work and focus on doing what you do best as a coach.

#Technology doesn't make coaches obsolete, it makes us more effective and productive, says @ExceedSPF. #athleteperformance #biofeedback Share on XNobody wants to make things unnecessarily complex, but the human body is a very complicated organism. While we never try to dumb down the process at Exceed, we understand that if the information is not bite-sized, it will likely backfire. We have rarely experienced a paralysis by analysis from information overload, but we do see an argument that too much feedback all the time can get messy. You don’t need to ensure everything all the time, but we never like making absolute statements of what we believe without getting a number we can trust.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF