The pressure is mounting. Strength and Conditioning coaches are feeling more and more that technology is the norm, and many have had to utilize technology they don’t fully understand just to tread water. Data and metric analytics are flooding into sport across the globe to quantify athletes’ historical, current, and projected win values.

It would be hard to argue against using technology in S&C in some form or another; in fact, the rise of Sports Science as a field of study indicates that, although we don’t yet have concrete methodologies, a competitive edge through physical performance metrics is within reach. We’re seeing more records broken, greater physical outputs, and more disparity between levels. As a sports performance professional, you’d be handcuffing yourself by not using technology to drive change, audit your own performance, and gain a competitive edge for your athletes.

Simply put, technological competence is no longer a suggestion in today’s job market. With the huge disparities between resources at different levels of sport, prospective sports performance coaches should actively pursue these skills so they can rise to the top of the resume-flooded desks of potential employers. This shouldn’t come as news to anyone reading this article, but just in case you needed the revelation: any resume you submit in this field is being evaluated in direct opposition to the career personal trainer who programs 5×25 back squat for strength work, and it’s left to the intelligence of the hiring committee to discern between the two. Unfortunately, this is why we still have to deal with people like “Coach X” at “University of YZ” (you know who I’m talking about here).

As a sports performance professional, you’d be handcuffing yourself by not using technology to drive change, audit your own performance, and gain a competitive edge for your athletes, says Connor Ryder. Share on XLots of factors play in, of course, but skill in sport tech is likely the lowest hanging fruit in terms of separating the top 10% from the bottom 10%. This is especially true for organizations looking to move in the direction of analytics and high performance.

Early on in my career, I decided it would be more advantageous to be ahead of the curve than trying to catch up down the line. I got lucky in that several mentors of mine had deep interests in this subject matter, so I did my best to be technically literate in things like Excel, statistical analyses, and critical thinking. Although I’m still early in my career, I’ve seen the payoff within every organization I’ve been a part of. As an intern, I earned more opportunity at times simply by finding gaps in the system that could be optimized through some simple formulas. As a Graduate Assistant at Springfield College, we were able to use more complex training methods because the backend data analysis took care of itself as part of an automated system. Now, I have a strong portfolio for the future to show my skill set and gain credibility within whatever organization I join.

I learned a lot from teaching myself these skills, and one of the biggest gaps I see now with technology implementation is lack of clear, practical strategy when laying the groundwork. As we work together to push this field forward, we’ll need to be more pointed with our planning, especially with the most over-complicated and underutilized performance concept we have at our disposal: load monitoring.

Load monitoring is the most global principle in sports performance. Using load monitoring technologies, a sports performance staff can maintain physical parameters for player health while building new lines of communication with sport coaches and administration that will open new avenues in player development. This is huge! We’re talking:

- Better performance

- Better health

- Better transparency

And, perhaps the most important aspect…better resource allocation. Data showing quantifiable value of a coach to an organization takes away the guess work from administrators who control the salaries and budgets. The wins are two-fold: admin is more comfortable with the hiring and negotiation process and performance coaches get better at their jobs (or are at least more incentivized to do so). So, when implementing load-monitoring, the system can’t be half-baked; it should be easily taught and learned, and all parties involved should frequently interacted with it.

Implementing Load Monitoring

Implementing load monitoring through technology can be daunting and overwhelming, especially when there are time constraints. Tons of athletes, not enough coaches, lack of tech literacy, and poor system automation are all barriers to entry in the field. If you don’t address these issues, frustration will rear its ugly head.

There are many ways to go about it, but here are five global considerations that worked to simplify things for me when I was given free reign over 44 GPS units for a Division 3 college football program:

1. Learn the hardware and software inside and out.

Collect a ton of data (tell the staff you are in the data collection phase). When I run into an issue, I do my best to solve it myself and jot down how I solved it. We’re talking the most basic of basic here: the GPS unit won’t turn on, the units didn’t charge overnight, data upload keeps failing, etc.

For example, a huge discussion for us prior to the start of pre-season camp one year was simply, “How do we want to go about distributing the GPS units to each player, and also make it as idiot-proof as possible?” Surprisingly, there are many different ways to go about this. We decided to whiteboard the process and determine how time-intensive each solution was. Essentially, we were diving down every rabbit hole we could imagine and working backwards from product (correct unit in vest, unit turned on, unit collecting data) to the most time-effective solution, knowing that we were working within a very tight preseason schedule that required our staff to set up and manage the entire system without physically being present when distribution took place. Ultimately, we decided on labeling units individually by name and allowing the position groups to select their vests in predetermined order, prioritizing larger athlete sizes first.

The best way to learn is to teach; by typing out the process, we were able to visualize what might happen if, for example, a brand-new intern had to take over and run our system in the event that we couldn’t, says Connor Ryder. Share on XOnce we decided on a step, I typed it into a document that could serve as an “instruction manual” for future preseasons and new interns/strength coaches. We did change the process a few times before settling on one we felt would work. The best way to learn is to teach; by typing out the process, we were able to visualize what might happen if, for example, a brand-new intern had to take over and run our system in the event that we couldn’t. This allowed us to identify all the holes and small details and to create a really effective, efficient model that accounts for all flaws while continuing to audit our own process.

2. Find things within the data you deem to be the most important physical qualities for performance.

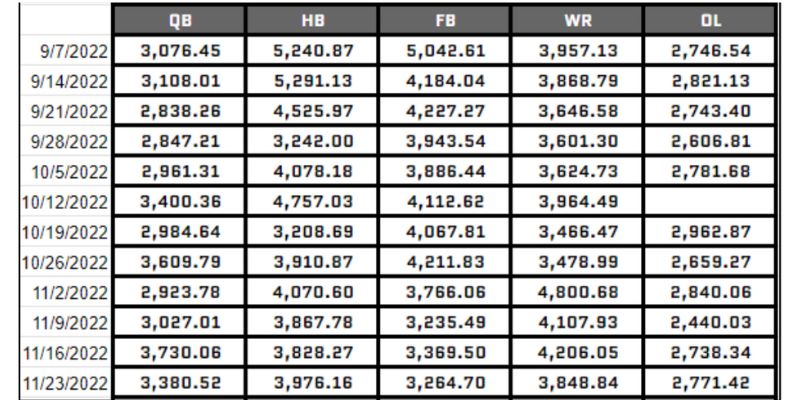

When S&C Coaches talk about programming, general sport demands (strength, acceleration, contact volumes) inform targets. Coaches can use these targets to work backward from the start of the season and determine their annual planning for volume, intensity, density, and duration. The same is true for load monitoring. From the data we collect, we can identify what normal practice or competitive demands are. If you’re actively using your tech, you should’ve collected a ton of data so far, so identify what a normal day looks like for each athlete (Image 1).

This is where data management starts to come into play (see #4). Identify where you are now, and where you need to be for each competition. You, and the sport coach, might be shocked to learn the stress you’re accumulating in practices relative to the next game.

3. Create a daily, weekly, and monthly report skeleton with the metrics you think are the most important.

The three general things to monitor are volume, intensity, and density (Image 2), plus some measure of acute/chronic workload ratio.

The way you display and communicate data is entirely up to you, and perhaps your coaching staff, if you feel they have valuable insight. Data collection over months and years will then give you the ability to relate these measures to correlations such as in-game performance and injury risk in conversations with other stakeholders.

4. Utilize a data management and storage system.

Yes, you can do this with Excel, and relatively easily, but storage becomes more difficult the more data you have. There’s an opportunity here to learn R or Python, and with OpenAI you’re only limited by availability and willingness. Learning those skills is easier said than done, but coaches have been figuring it out for years now, so the ball is in your court! Your end goal for data storage and management should be filtering data into your reporting skeleton.

This is a problem we ran into when transitioning our system, which was built in Excel, from in-season to spring ball, and one that needed to be solved pretty quickly. We didn’t want to use the same load monitoring structure as in-season, because games aren’t played at the end of each spring ball week (of course). The strength and conditioning staff knew that the data mattered, but we didn’t know exactly why it mattered to us.

The data management system we built in Excel was only meant to track practice loads and relate those loads to games. That isn’t inherently bad, since we do ultimately believe that we should be training our athletes to withstand game volumes, but we were handcuffed at the time by the system’s capabilities. I now understand that data management is best done with fully independent of variables that get filtered and sorted later on in the data analysis process.

By utilizing a system intended for large amounts of data, such as R, Python, or AMS (Athlete Management System) products like Smartabase or Kitman Labs, we can store all data and pull only what we need in the moment to answer performance questions efficiently and effectively.

5. Run your system and evaluate it thoroughly and objectively.

Try to avoid showing your system to anyone who might have preconceived notions about what immediate value they’re getting, such as the sport coach or administrator who invested in the equipment. Pick your system apart and find where you’re taking a ton of time; then, reevaluate that step.

Pick your system apart and find where you’re taking a ton of time; then, reevaluate that step. Share on XChances are that there’s an easier, more efficient way to make your system as autonomous as possible whilst providing as much actionable data as possible. Upon analysis, you might even find that some of the metrics you initially selected are inconsequential to performance or injury; you can’t find these things without trial and error, so use best judgment and make sure to audit yourself frequently until you feel as though your investment has paid for itself in value.

Communicating Your Results

Until you’re immensely comfortable with the weight of the amount of time you’re investing daily and the amount of return you’re getting from the data (daily and longitudinally), maintaining an eye of skepticism can be highly valuable. Eventually, you should feel as though you could explain your system to a toddler. At this point, don’t be afraid to get on the same page with your immediate staff (assistants, interns, AT), and finally meet with the sport coach to discuss what you both feel are best practices for implementation.

This theme continues down to the athletes: outline the process, show them the data, and explain their role going forward. Athletes want to stay on the field; they want to improve; and they want to compete. I think of these as the team culture application of the three innate psychological needs from Self Determination Theory (autonomy, competence, relatedness). Strength and conditioning practices that circle back on these basic needs are guaranteed successes when applied strategically. Conversely, any practice that fails to display alignment with these needs will fail for compliance reasons.

Implementing the system and enacting change is where the art of coaching comes into play; we can find infinitely creative ways to strategize. Reports, leaderboards, conversations, presentations—whatever you can think of—can all be effective. The caveat is in proactively creating a system where the product is a tool as opposed to a hindrance.

I want to make an important note here to wrap things up: although we talked mostly in terms of GPS load monitoring here, we can apply these these thinking frameworks globally. We have to wear a lot of hats in this field, and the less we’re sidelined by tunnel vision, the better off we’ll be.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Kylah Broadnax is a dedicated and dynamic professional with a rich background in athletics and fitness. A former collegiate volleyball player at Midwestern State University, Ky’s passion for sports and fitness led her to transition into personal training (beginning in 2019) and coaching club volleyball (2017-2023).

Kylah Broadnax is a dedicated and dynamic professional with a rich background in athletics and fitness. A former collegiate volleyball player at Midwestern State University, Ky’s passion for sports and fitness led her to transition into personal training (beginning in 2019) and coaching club volleyball (2017-2023).