Ryan Reynolds enters his sixth NFL season with Kansas City in 2021 as the club’s Strength and Conditioning Assistant and Sports Science Director. Prior to working for the Chiefs, he served as the Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach for the UCLA Bruins football team for four seasons (2012-2016). He also spent time with Arizona State University’s football program as an assistant coach focusing on sports performance (2008-2012) and as a sports performance graduate assistant for the university’s basketball and football teams (2006-2008). Between those two roles at ASU, Reynolds served as a sports performance assistant for the University of Louisville’s football team (2008).

Reynolds got his start as an intern for the University of Iowa, focusing on men’s basketball, Olympic sports, and football strength and conditioning (2001-2006). He graduated with a B.S. in Exercise Science from the University of Iowa in 2005 and an M.Ed. from Arizona State University in 2007.

Freelap USA: Hip extension, specifically in the hamstrings and glutes, requires the generation of rapid force. You have an affinity for tracking athletes in the weight room and managing power during a long season. If programmed correctly, is it possible for pro athletes to truly peak later in the season if they start off right?

Ryan Reynolds: I would say that it is absolutely possible for pro athletes to truly peak later in the season, based off my experiences the last 3-4 years. If a large portion of your roster DISPLAYS to you that they have a physical quality (e.g., max strength) north of or on par with off-season or early season values, I think that speaks to two things: ultra-precise programming (volumes/intensities) and “the eye of the coach.” If only one is present, it will not work.

People mistake this for “maxing guys out” late in the year, which couldn’t be further from the truth and just highlights the lack of understanding of how to accomplish it. Lots of factors are in play here, but after a year or two, you know what you are getting from a practice standpoint. So, it comes down to being able to do the right things at the right times in the weight room to make sure the physical quality of strength stays in place.

Lowering weights to chase a speed number on a barbell and calling it power/speed training defeats the purpose of ‘training power, strength, and speed.’ Share on XThat is critical to having a strength reserve and a place where all other velocity-based physical qualities like power and speed can launch from. Lowering weights to chase a speed number on a barbell and calling it power/speed training defeats the purpose of “training power, strength, and speed.” Applying ultra-precise training and programming to illicit a training response that will actually peak guys late in the year instead of making home plate bigger, so to speak, has been the key for me.

Freelap USA: Continuing education is vital to your growth as a coach. You travel extensively and work hard on getting cutting-edge information that is both scientific and practical. Can you share a few tips for young coaches to network with the RIGHT experts? How do you spend your off-season?

Ryan Reynolds: Being able to identify the RIGHT experts is the most critical aspect of a very directed and purposeful continuing education. Being surrounded by great people helps this tremendously, as your “filter” for information becomes very refined. Over time, it is very easy to identify where you need to place your efforts and where will be a waste of time. I would recommend looking internationally, as there are some tremendous people out there doing real solid work that will have a big impact on the refinements you make year to year with your program. This has really served me well.

Take your time and really read the research, talk to the best of the best in those areas, and over time you will build a case for why to accept or reject certain “new” methods or trendy things pushed on social media. Normally, I’ll spend my off-season traveling as much as I can, accessing the experts I have identified throughout the year, and reading the subject matter so we can be very efficient with our time.

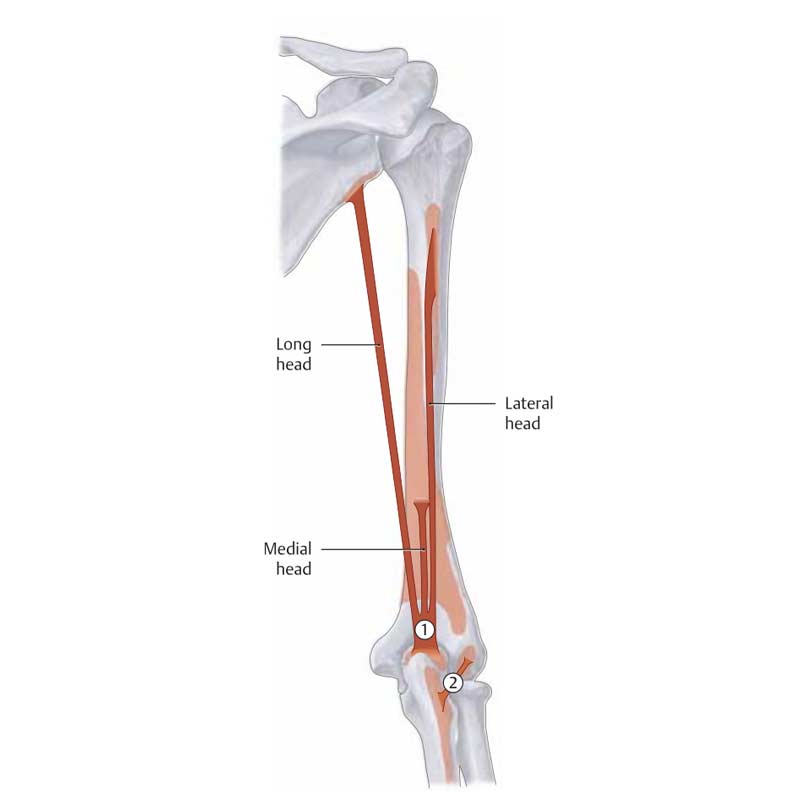

Freelap USA: The anatomy of the hamstrings is unique for each athlete, and many coaches are now doing cadaver reviews or ultrasonic analysis. In your mind, what could be the culprit behind injuries with athletes who have good “Nordic” scores but still pull? Often load management isn’t the problem either.

Ryan Reynolds: This is a hot topic of late, and the latest research that has come out has really shed light on it. The early adapters in the long and strong crowd are now seeing paper after paper, especially out of Australia with pro athletes (Aussie Rules, rugby, etc.), showing over the course of seasons and years studies with the subjects’ Nordic mean values climbing substantially but yet injury rates remaining the same. I feel it’s well established that hamstring injury is multifactorial, and Nordics may have a place in certain instances (proximal BFsh problem), but we have to do better than just think doing a weight room exercise will solve the issue.

In my mind, the issue comes down to whether you are doing things on your end that actually move the needle in terms of tissue adaptation and neuromuscular timing to feel good about things. Are you exposing them to enough true sprint and speed worked COACHED at a detailed level? Volume isn’t equal to volume if the coaching is good and detailed. It’s impossible to replace a good coach who can get things going right as opposed to someone just administering the workout.

We know not all injuries can be prevented, and we know what we do is merely an attempt to reduce the risk of injury, but it is definitely much more than a load management problem in most cases. Share on XOther areas to consider would be reaction to the ground (plyos), good-quality balanced lifting in the weight room, pelvic positioning, hip extension (coordination of hamstring and glute), hamstring/hip flexor extensibility, etc. We know not all injuries can be prevented, and we know what we do is merely an attempt to reduce the risk of injury, but it is definitely much more than a load management problem in most cases.

Freelap USA: Mental fatigue from a very technical sport like football can manifest in both mood and physical performance. How can high school coaches use simple wellness scores to help monitor fatigue in a smarter way than being dependent on readiness tests that may not work with large groups?

Ryan Reynolds: Mental well-being is such a big part of effort and attitude, and this is important at the high school level, as you want athletes to enjoy it and walk out feeling so. Having them wanting to come back is the goal, so you can continue to make progress and stack training days on top of training days. Overreliance on readiness tests in such a large group usually ends up as paralysis by analysis and then nobody gets anywhere.

Best to use that information on an individual basis to “have a conversation” with them and to find out what’s going on or if they need help with anything. Through these conversations, you will build better trust from your athletes. Building relationships is a big part of being able to coach someone and tell them something they may not want to hear. Use the information obtained to have the conversation on why maybe their readiness isn’t well. This is a great way to open the lines of communication and even direct training for them.

Freelap USA: Medical health, specifically of the spine and foot, is a growing interest in football due to the speed of the game. Your program addresses resiliency with heavy strength training to protect tendons and ligaments. Can you share the needs of deceleration and rate of torque with the change of direction sports? Sprinting may be a vaccine for hamstring health, but conventional strength training works as well. Can you share the importance of raw, heavy weight training and player longevity?

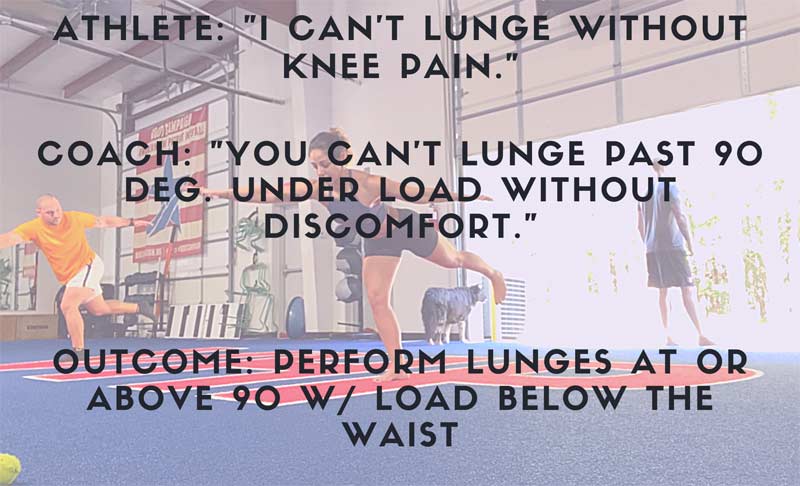

Ryan Reynolds: Deceleration and rate of torque with the change of direction in sports is definitely a part of what happens on the field of play. If we picture the athlete as a wave coming in off the ocean and crashing into a seawall, that seawall had better have the strength and integrity to redirect that wave. This is essentially what is happening with change of direction and the redirection of forces and momentum.

Conventional strength training is a huge part of that to develop strength in deep knee bend positions and any other joint angle you must go through to get there. This is especially critical in most fast twitch guys, who most often rely on a very ligament-dominant strategy. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out fatigue, and over the course of the long season and over a career if you don’t address raw, heavy weight training, it can end in disaster. I’d rather do what we know can have a benefit than just rely on the sit, wait, and pray approach.

For some reason, this fear of raw weight training with loads has begun, but you don’t hear the conversations on the benefits of tendons and ligaments or hormonal responses over time. Maybe not enough people have invested time in the classic Viru text or read Komi, etc. Again, having a coach who can use raw, heavy strength training and put guys in positions in squats, pulls, press, and Olympic lifts or their variations will be much more effective and actually CEMENT true long-lasting adaptations that get guys through the season and their careers.

Emphasis changes over the course of a career but being able to do a few things well will pay huge dividends. Share on XEmphasis changes over the course of a career but being able to do a few things well will pay huge dividends. The ability to display strength in a deep knee position in a squat with barbell over midfoot and the ability to have the postural strength to put the bar where you want it in an Olympic lift/derivative and create a vertical impulse on the bar are two of the most important things in the weight room.

I’ve seen too many athletes who, after being trained specific for years and years, couldn’t squat without a hard hinge point in the lower thoracic spine and a huge forward torso lean because they were most likely cued a certain way. Then the squat and lifting become the bad guys. Nothing beats good, solid, raw, conventional training when things are done correctly, and the program is fit to the athlete and not the other way around.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF