To Catch or not to Catch, that is the question!

Let’s get to it—I prefer the Clean High Pull to the Power Clean in the competitive, athletic population. I will provide some common sense and scientific support for my claim that might persuade some readers and, at the least, get folks to think a bit. Note that I’m not implying that Olympic-style weightlifters (who I refer to as weightlifters from here on out) are not athletic. However, for this article, “athletic population” will refer to non-competitive weightlifters: those who weight lift to help them in their sport. “Weightlifters” will refer to those athletes whose sport is only weightlifting.

The Power Clean and Clean High Pull in Athletics

The power clean has been around for at least my 35-year coaching tenure and will continue far past it. As a former short-time competitive weightlifter and mentee of the likes of John Garhammer, Bob Takano, Bob Ward, Harvey Newton, and Al Vermeil, not only do I love the lift but some of the best coaches taught me the lift and the science! This includes the 1980 Garhammer paper I still believe is the foundational work on the lifts, “Power production by Olympic weightlifters” in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise (MSSE). More about this body of work later.

So, full disclosure, I love the lift and the physiological and biomechanical contributions it makes to the appropriate sports. That said, and as I have said many times before, I don’t want to do what works… I want to do what works best! Over the years, I have questioned several philosophies and methods (as we all should), and have proven to myself through educational recourse that just because we have done something for a while, it doesn’t confirm that it is the best option.

Thomas Paine said, “A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right…” No place exemplifies this like athletics; in particular, strength and conditioning. And it wasn’t until 10 years ago, after several re-reads of Garhammer’s research, that it hit me that the power clean might fall under the “this-is-what-we’ve-always-done” heading.

Problems with the Power Clean

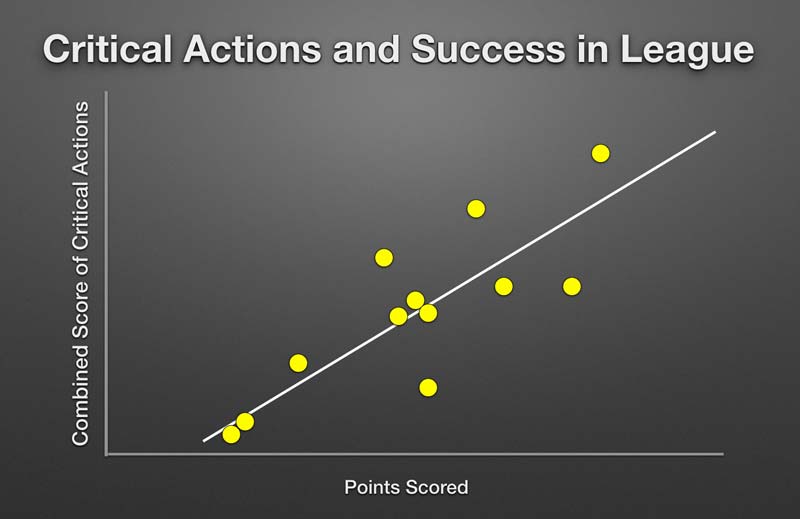

It’s easy to adopt the power clean as THE lift to do for athletes, considering that jumping high and running fast are important for athletic success. There is no shortage of papers on Olympic lifts and their relationship to vertical jumping. These include Canavan, P.K., et. al. (1996), Garhammer, J., et. al. (1992), and Stone, M.H., et al. (1980), to name a very few. Vertical jumping and the power clean have similar biomechanical characteristics.

In addition, physiology and biomechanics can lead one to a safe hypothesis (there are very few focused studies) that, if an athlete can jump high, they most likely are fast in sprints shorter than 20 yards. Anecdotally, we’ve all heard the stories of those who power clean big weights and jump high as well. Jim Schmitz, in the article “Jumping and Weightlifting” for IronMind, talks of world-class weightlifters and their jumping feats:

“When Ken Patera (the first American to clean and press and clean and jerk 500 lb. (227 kg) was training with me in 1972, I told him that I had read that Paul Anderson (1956 Olympic Champion and considered the strongest man that ever lived) could do a standing long jump of 10’ (3 m). Ken said he was sure he could exceed that and told me to get a tape measure. I did and we marked his starting point. With a slight dip he jumped, and we measured 10’-6” (3.2 m). He said, “Let me try that again,” so he did and this time we measured 11’ (3.35 m)! Ken said he was sure he could go further, but the landing was hurting his knees since he weighed 335 lb. (152 kg) at the time.

…Another lifter who could jump was Tom Stock (1978, 1979, and 1980 U.S. champion super heavyweight), who could do a vertical jump and reach of 39.3” (1 m) at a bodyweight of 303 lb. (137.5 kg) and height of 6’-1” (1.85 m). Mark Henry (1992 and 1996 U.S. super heavyweight Olympian) could dunk a basketball at a bodyweight of around 374 lb. (170 kg) and a height of 6’-2” (1.87 m). Shane Hamman (U.S. super heavyweight record holder and 2000 and 2004 Olympian) was also reported to be able to dunk a basketball at a bodyweight of 352 lb. (160 kg) and at a height of 5’- 9” (1.75 m).”

I certainly understand all this and have for nearly 35 years, but here are a few of my problems with the power clean:

1. Nothing about the catch (turning the bar over and landing it on the shoulder) translates to the field, pool, or court.

The only non-athletic thing about the power clean IS the catch! This is biomechanically and physiologically useless for an athlete to help improve sports performance. Yet, special steps must be taken to teach the maneuver—increase flexibility of the wrist, include front squat into a program to help teach the “rack,” or separate rack flexibility exercises. Wrist inflexibility seems to be the biggest issue with the catch, and at times detracts from the very thing we are trying to achieve—power!

For example, both Athletes A and B pull the same load (140kgs) to the same height, proportional to their stature. Athlete A “racks” the bar in good form for a max 1RM. However, due to wrist issues, Athlete B cannot rack the load but was successful at a lighter load (120kgs) for no other reason than it was lighter; his 1RM is 120kgs. We all know this happens too often.

In this case, the power developed during the second pull was the same for both athletes, but Athlete B gets penalized not for power output, which we are trying to achieve, but for wrist inflexibility. Also, because of that, the power clean data—data indicating power—is now unreliable because Athlete B (and perhaps others) are being judged on wrist flexibility and not peak or average power.

2. Catch depths are different from athlete to athlete.

Split catches, catching the bar with feet spread even wider than a wide squat stance, and ¼-½-¾-full squat catch positions all significantly change the dynamics of the lift, specifically pulling height and squat strength contribution. Here again, any data gathered for team averages is not valid or reliable unless every athlete catches the bar at the same height in a similar manner.

3. The catch is more important than the lift.

In other words, as long as you catch it, it’s good! Whatever happens between the ground and the catch is an “oh well” proposition. It’s painful to watch bad technique on posted videos and there is no shortage of that. Some folks should plead the fifth because the clips are incriminating evidence of bad coaching. Legs straightening at liftoff (moment of separation—MOS); backs rounding coming out of a squat of any depth; hips rising before the shoulders; bars rolling from chest to shoulder upon contacting the body; bar trajectories that are too far from the body and, as a result, the lifter hops forward; elbows too close to the body; and on and on.

When I watch these videos, I can only assume that the catch is all that is asked for. I’d be the first to say—although I might be Boyleing (a Mike Boyle saying turned into a verb)—that you can literally correct some technical aspect of the power clean on every rep. It’ll never be perfect, especially with a population that does more than just lift. Still, the most important parts of the lift are everything except the catch, from the moment the bar separates from the platform to the second pull just above waist height. A fact that is not trivial: If an athlete’s MOS is not good, the remainder of the lift cannot be corrected and therefore is not good… Even if there is a catch, it should be red-lighted!!

Using the Power Clean Way Too Early in the Training

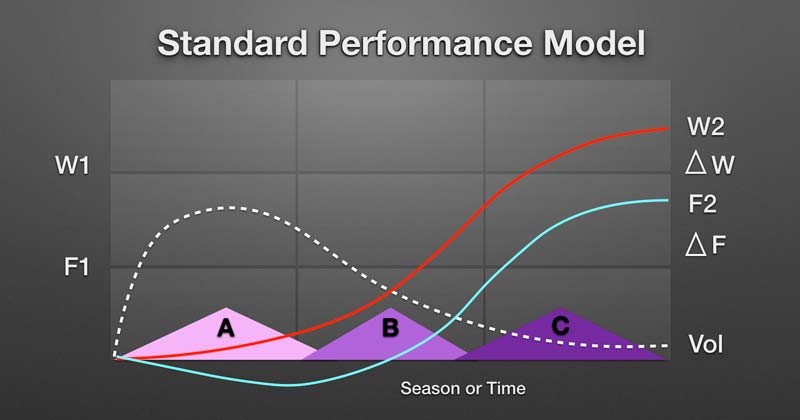

During Robert Newton’s presentation, “Latest in Strength and Conditioning – ACSS 2013 Keynote Address- Part 1 of 2,” he illustrates and discusses power training versus strength training. His question is the same as ours with “not strong” athletes—collegiately, this would be the inexperienced and weaker frosh group or those that have not acquired a strength standard—is “What do we do?” Do we do power training (e.g., Olympic lifts), or should we get them strong first?

Beginning with the power clean early in the training experience is ineffective in creating power, says @Coach_Alejo. Share on XMy hope is that I force you to watch the entirety of Newton’s fantastic presentation by not going into too much detail here. Nevertheless, his conclusions show that those that start power training first produce less power than those who strength train first and power train later in the same given time period. Then there’s the four weeks or more of teaching the phases of the lift (I’ve seen coaches spend too much time on the phases, most of which the athlete never adopts), where there is not enough load to get any sort of strength OR power adaptation during that time period. And, with all the time constraints collegiately and coaches complaining of how little time they have, beginning with the power clean early in the training experience is ineffective in creating power and a poor use of time.

As a side note, squat cleans are killing the emphasis on vertical explosion—pulling height, triple extension.

As a reminder here, I am talking about the athletic population, not the weightlifting community. However, the weightlifters are my comparison. Weightlifters perfectly match the speed, load, and effort so that the height they pull the bar is as high as they can pull it. It is a rare athlete that matches the speed, load, and effort.

What I’m seeing is athletes pulling the bar just high enough—when it appears to be a load that can be pulled higher—to get underneath the bar to squat it. And, in several cases, the weight being squatted looks to be pretty damn heavy in comparison to the pull as witnessed by rounded backs. The opposite is true for many weightlifters—it’s the pull that is the most difficult piece; rising out of the squat is easier if not the same difficulty. By the way, when a light weight is pulled to sub-max height, this means the athlete has purposely slowed the bar down. What other top-end powerful movement arises when velocity is purposely decreased?

So then, I ask, “Why are we performing the clean?” Clearly not for power, if it’s not max speed for the load and therefore not max height. If the answer is that squat strength is being targeted, then why not just have a great squat program and work on power by producing more speed and effort and catch the bar higher in a quarter-half squat position? Or taking a page from weightlifters, why not do a 2+2: two power cleans + two front squats?!

Looking at the Clean High Pull

“…most of the mechanical work of lifting the barbell (snatch) and his (athlete) center of mass by the time the bar has reached a position slightly above waist height. At this instance his body is fully extended and supported on the balls of the feet, the bar has reached its maximum velocity, and the force applied to the bar has decreased to almost zero.”

–John Garhammer, “Power production by Olympic weightlifters”

Although Garhammer is alluding to the snatch here, you can hypothesize that the power clean and most of its virtues come to an end after the bar reaches approximately waist height or so. My concern is that most coaches know how to coach the lift, or at least have gone to good sources to learn how to coach the lift, but do not know the kinesiology of the lift. I think the lift is taken for granted for no other reason than everyone does it.

There’s always talk of the physiology and movement related to the lift, its benefits to sport, and how it must therefore be good—and it is—but I don’t think it’s the best option given the intent. I know the clean high pull is the best option for producing power effectively, triple extension, and terrific technique, all of which contribute to common physical characteristics needed for success in sports.

Why the Clean High Pull?

Part of this answer has already been mentioned earlier as some of my issues with the power clean. Here are a few more reasons: The clean high pull is easier to teach and execute, is more versatile in relation to different speeds and pull heights, has less (if any) of a chance of cutting the pull short if coached correctly, is easier to assess individually or as a team, always matches load to effort, and can always match load to speed.

I know the clean high pull is the best option for producing power effectively…and great technique, says @Coach_Alejo. Share on X1. Focus on Vertical Explosion

With the clean high pull, there is no wondering about when to get under the bar, producing vertical power, catching the bar but not being able to come out of the squat—thus missing the lift—or worrying about wrist inflexibility at heavier loads. You just pull as hard and as high as possible! And there are no worries about coming off the ground in proper position—if coached well, the weight will be submaximal to weights lifted prior. I have experienced my share of high pull maxes surpassing the clean deadlift maxes at some point, so that’s something to think about. At every weight, the athlete pulls as hard and as high as possible. So much so that it’s not unusual for stronger athletes to pull the warm-up loads nose-high or at some point begin with light snatches as a warmup.

2. Absolute Measure of a Green-Lighted Lift

I remember reading in a research paper that, in that particular study, during the competitive snatch the barbell was fixed overhead at two-thirds of the lifter’s body height. Higher or lower is not the issue, but I knew I couldn’t test the pull unless I had a stable testing protocol; a conclusive point. I also knew that I wanted a faster, higher pull because the athletic population needed that versus a slower/lower pull—I wanted an extended pull, not a jump shrug, which I think is a training mistake. I settled on sternum height at the xiphoid process. In a team setting, I wasn’t going to record every lift in slow motion to see that the lift was exactly at sternum height, if only as a practical matter. But for my purposes, it was reliable across the groups.

3. Teaching from the Bottom Up for an Earlier and Better Strength Base

I like the bottom up, or if pushed, another method that I and Craig Sowers, the former Director of Olympic Sports at NC State, termed “convergence.” My primary reason for teaching from the ground first is so that we can immediately work on strength. Very, very few exercises connect the posterior chain in unison better than the clean deadlift. Okay, the first day or two is limited to technical aspects, but every day after we add weight. Plus, if I have a strong belief in the MOS, the fundamental piece of any pull from the ground, wouldn’t it be the first thing I would work on?

It’s called intent: What am I doing and why. Convergence is working from the bottom up and from the top down within the same training phases. If a coach is compelled to work on the top portion of the lift first, so be it. Nevertheless, you can’t ignore the necessary strength needed from the floor if you want to produce optimal and peak power and speed. So, perform a solid clean deadlift routine one to two times per week and schedule some low-volume and low-intensity work on the second pull one to two times per week.

4. Less Complex Technique Than the Power Clean and, Thus, Easier to Learn/Teach

It’s all in the title. There are two teaching phases of the lift, and they’re easily taught and therefore easily learned. All for more power and speed! I will emphasize that the clean deadlift makes a huge contribution to learning the clean high pull for one reason: half of the clean high pull is technically sound and the athlete is adequately strong after 30+ weeks of repetitious technique and strength acquisition.

No one can deny that it takes weeks, if not months, for a power clean to look like a power clean and to use a load that allows for any benefit while learning. Haug, et al., 2015 (thanks Tim Suchomel) points out that it took a “minimal investment of 4 weeks to achieve increases in vertical power production.” Aren’t we always talking about how little time we have?! I promise you that on the first day and first rep of high pulling, a benefit is gained. Here again, density of training and time is the key—less time to teach for more power and speed.

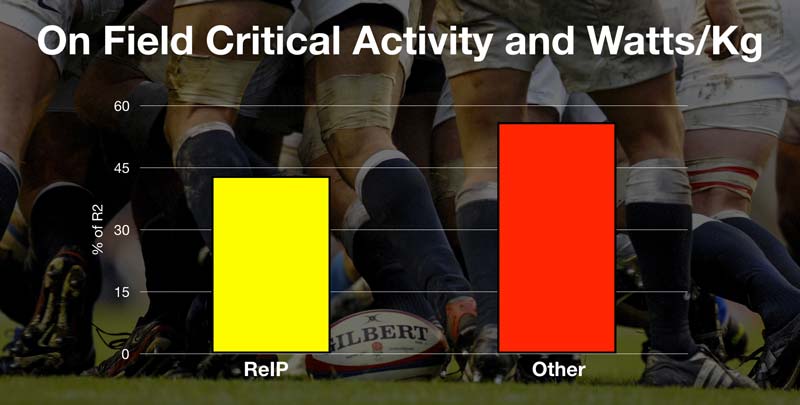

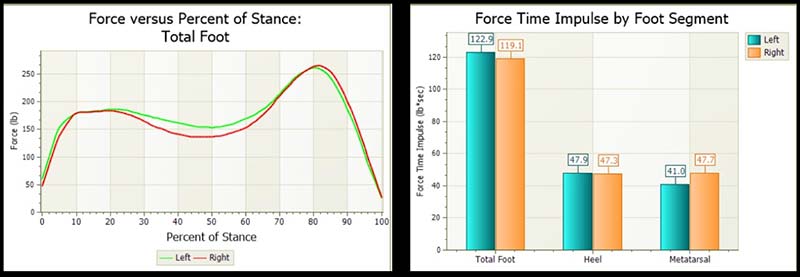

5. Better Manipulation of Intensities for a Full Force-Velocity Effect

As Dr. Suchomel puts it (more about Tim and his research later), “force-velocity overload” can occur over a variety of successful pulling ranges. With a power clean, it’s a clean or it isn’t—there’s no work in between. Essentially, there are more benefits from the pull that cannot be achieved with a catch.

If you want to work on the strength end of the spectrum, work at heavier loads can be executed and remain at high speed with a slightly lower pull height. Higher velocities (higher pulling heights) can be performed at lighter loads without compromising technique. Unfortunately, the power clean is one of the few exercises where the load must be heavy enough to correctly execute it; a pull too high means the bar crashes the shoulders on the catch. In addition, assigning an arbitrary range of 70-80% for best power outputs is a mistake, especially when the pulls are not max effort or height.

With a power clean, it’s a clean or it isn’t—there’s no work in between. Essentially, there are more benefits from the pull that cannot be achieved with a catch.

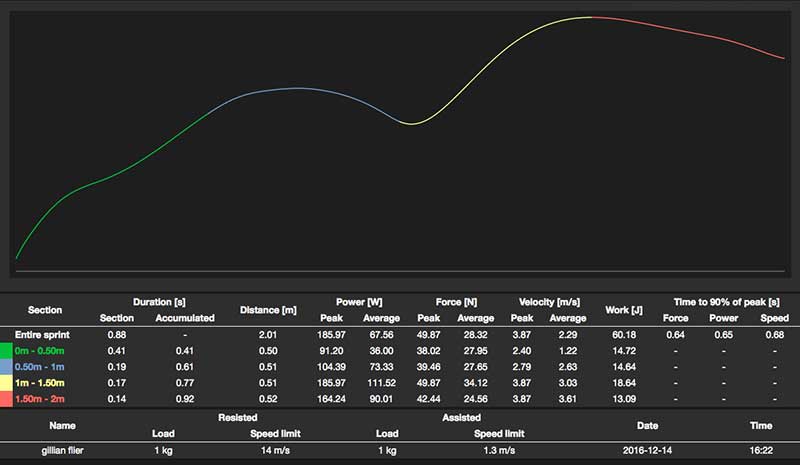

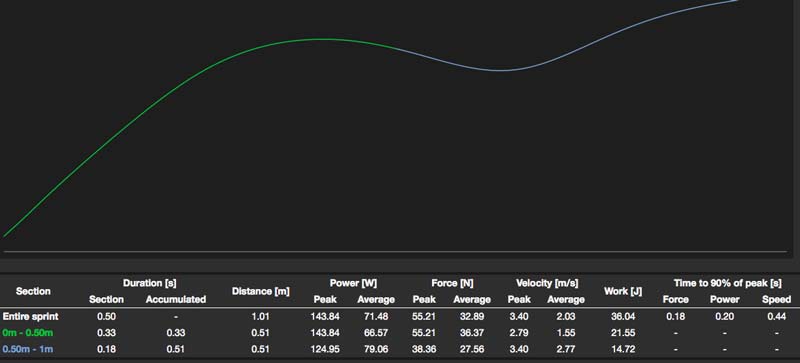

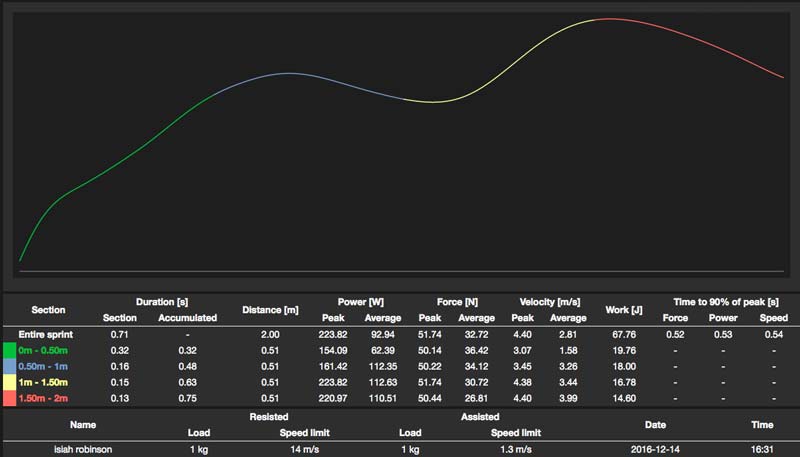

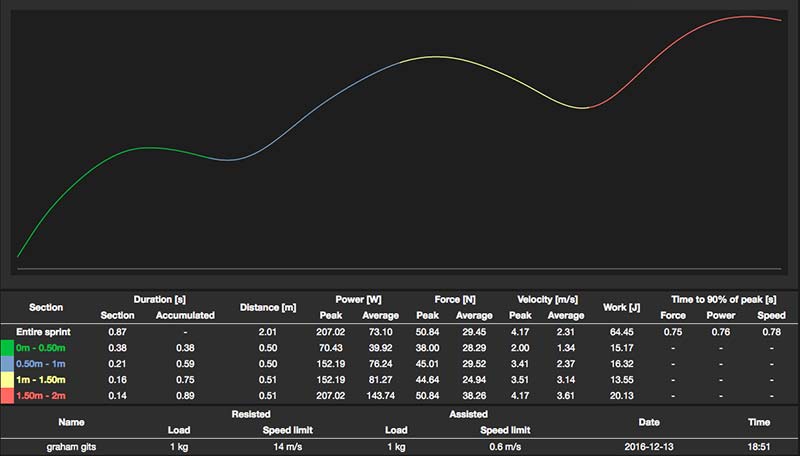

Tracking bar speeds and power out of the clean high pull with the Power Lift laser, I found that top power outputs were occurring at 75-82.5% with speeds of 2.39m/s-1.59m/s, and I programmed each individual based on their max speed or power where applicable. Not coincidentally, the strongest athletes had the best pulling speed.

The First Step: The Clean Deadlift

First, the progression begins with the clean-style deadlift! I believe as strongly in this as I do the clean high pull. I propose that collegiate freshmen, transfers, or a beginner at any age for that matter, clean-style deadlift for at least 15 weeks of strength and technical emphasis in addition to one in-season cycle. I have found the percentage increase in strength, as well as the downside of staying too long in a strength phase, dictate the length of period I mentioned. You can count on the athlete setting a new deadlift 1RM during the season.

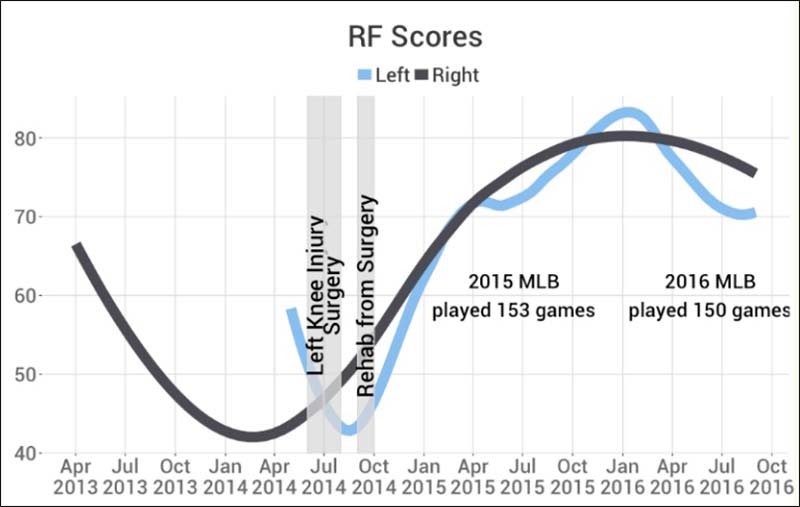

In the example of a freshman NCAA basketball player, it will be 16-21 weeks of strength and technical acquisition depending on what summer session they attend. This will happen in a 25-week period that has four weeks of no training due to breaks in the academic calendar. Next come 18 in-season weeks (low to very low volume, 60%-90%), not including post-season play. After two to four weeks of complete rest at the end of the season the new athlete will start the first day of clean high pulls.

Using NCAA soccer newcomers as an example, the heavy internal/external load of pre-season practice—magnified by athletes playing on summer teams and having little time for strength or conditioning sessions—is the perfect ground for very low volume technical work with a slow overload progression during the season. In this way, the technique should be solid by the start of the spring strength training cycle, and then it’s just a matter of choosing the right time and pace to overload up until the end of the school year. Returning for the second pre-season, again, it’s a great time for low-volume teaching and acquiring new power with the clean high pull. Coat-tailing onto Dr. Newton’s presentation, stronger athletes adapt to power training faster than those who start with power training, which supports beginning with strength work before the explosive movements.

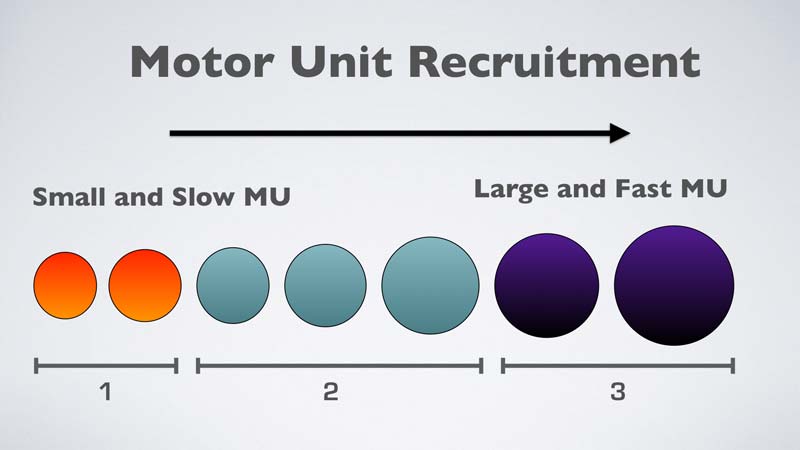

The question could be, “If you are not performing a ballistic lift, what do you do to create power?” The easy science-based answer is, “We are creating power.” With inexperienced lifters, and experienced lifters that are inexperienced with pulling from the ground, gaining strength means improving power! The formula for power seems to be generally abused, and viewed as one-sided. The discussion is nearly always about creating speed to get power and the strength part of the equation is ignored. More often than not, strength is the limiting factor in creating power for no other reason than coaches like to get to the complex, exciting stuff before the athlete is strong enough to fully benefit from it.

Training for power and power training are two different things with the same outcome. In the weaker athlete, it’s summarized like this: The stronger you get, the higher you jump and the faster you run. Therefore, in that group, getting stronger is training for power. Full disclosure: During this base phase of deadlifting, the athletes performs a jump up on a box (24-36”) after each set for two repetitions. This teaches full vertical extension. The technique is simple to coach: the athlete should land on top of the box in the same position (hip, knee, and hip angle) as the takeoff.

The athlete must be technically efficient with the heaviest weight possible from the ground. To produce the fastest speeds at the heaviest loads while high pulling—or “cleaning”—the athlete must be able to optimize maximal strength AND technique during the first pull. I’m convinced that, to optimize the best weight to high pull, the deadlift must be close to topped out for two reasons:

- You should never worry about whether you can get the weight off the ground correctly—never a concern for a weightlifter—let alone wonder if you can violently, vertically explode with the bar, catch, or no catch.

- Reaching close to ceiling-level strength in the deadlift means that significant strength will not be a factor while learning the pull, when beginning at 40-50% of a 1RM clean deadlift.

Progression to the High Pull with the Clean

There are no phases here. My cues are visual (I demo) and audio (I describe what I want) and simple. Plus, they’ve already had the visual of seeing their teammates perform the clean high pull for months. As an example for our interns, I call them over and tell them that, while they’ve heard me describe the simple step in teaching the clean high pull, I want them to witness it firsthand. It goes like this:

Me: Deadlift the bar to just above the knee. When the bar gets here (pointing to the spot above the knee, as well as demonstrating the position), jump and pull the bar elbows high and bar close to the body.

Nine times out of 10 (no actual data for all you era-of-big-data folks), the athlete hits the first rep pretty damn well! That is to say, I don’t have much to fix at all. It’s not as if I have not personally dissected the lift from floor to catch and all positions in between—I have. I also believe that once you understand the entire lift from floor to finish (positions, transitions, cues), only then will the athlete you coach gain the most benefit.

That said, in all my years (with the exception of weightlifters), I have not seen the virtue in emphasizing positions for one to four weeks or more versus my description of the teaching method. Heresy? In the eyes of some. I just think those eyes are not saying “What works best.” It’s kind of like today’s training cards, which have morphed into PowerPoints with all the colors, grids, exercise, warmups, and technical lists! Some say it’s for the athletes’ benefit. I say the athletes could care less. The athletes just want to know what they should do; they don’t care what color or what artistic way somebody presents it. This seems mostly for the coach’s benefit.

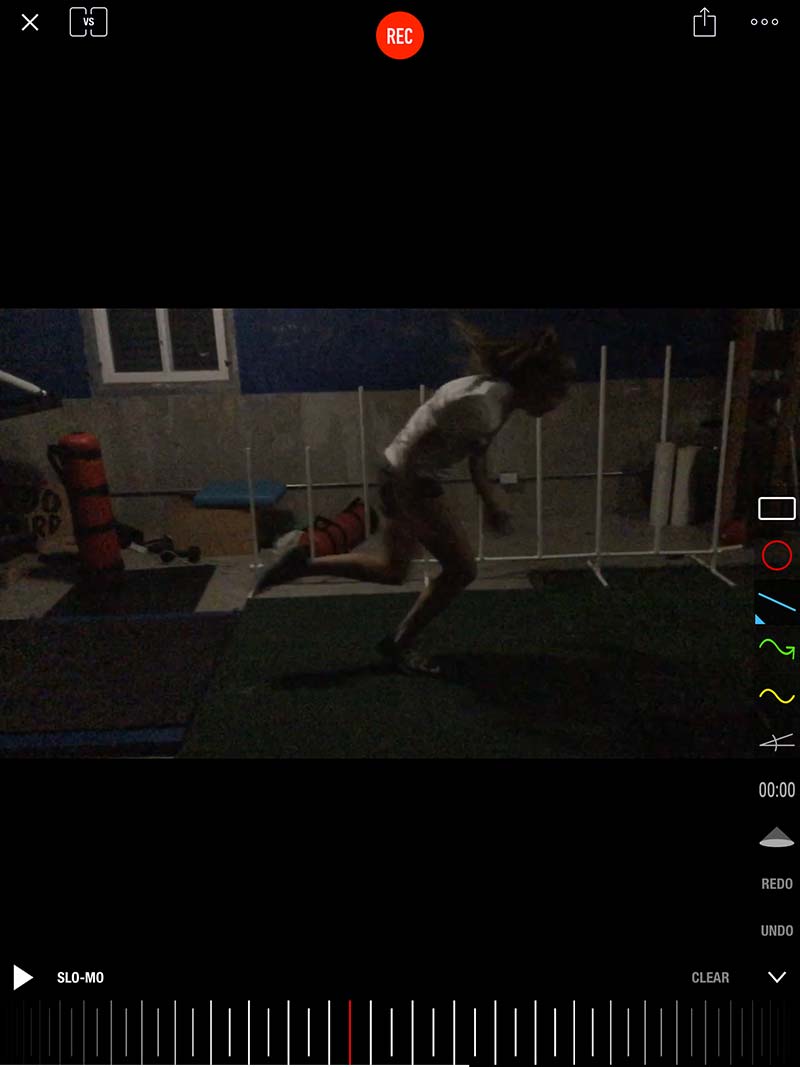

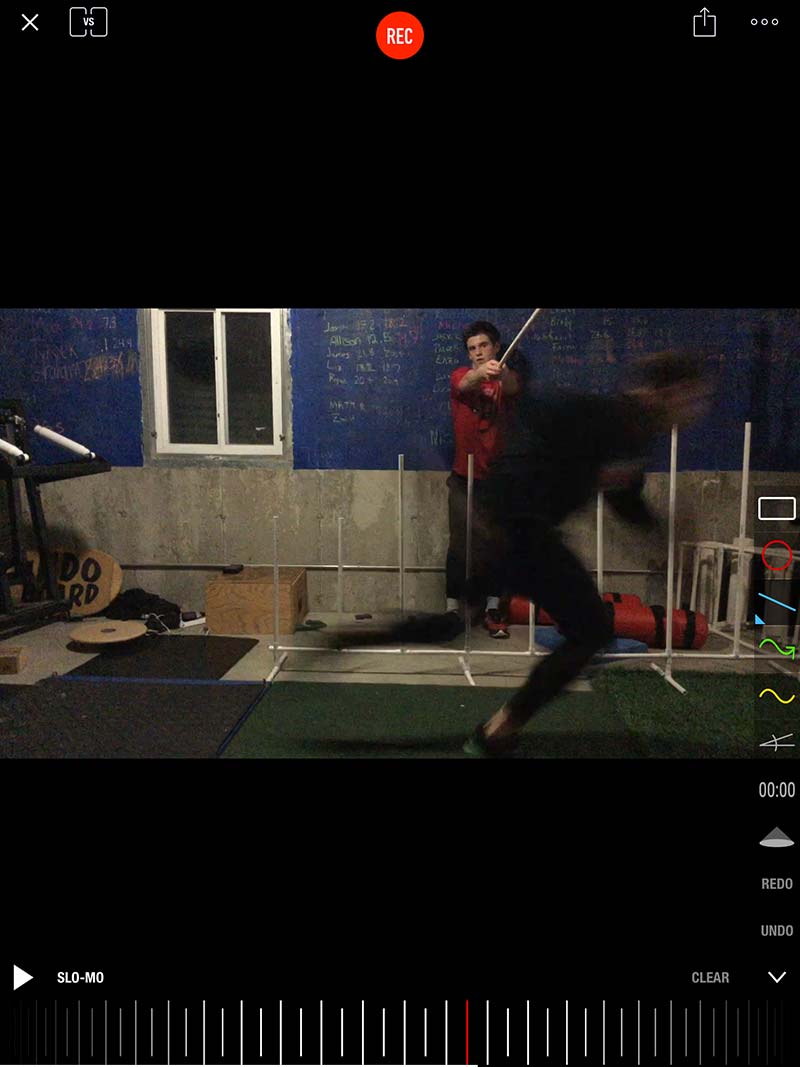

Video 1: The conventional clean pull has a lower projection of the bar, but similar benefits. The clean high pull comes farther up than this, and other variations exist, such as using blocks or racks. Source: Brad Deweese.

There are some who say, “I don’t like the high pulls because my athletes drop down after the pull.” To those I reply, “They don’t drop down to catch the bar in a power clean?” Some also say, “I don’t like when they spread their feet out like a jumping jack after the pull.” Frankly, I don’t care if they moonwalk after the high pull. As long as they get to the position shown in the picture, which is the position we are training for, I’m good with it because we are getting the training intent and effect.

Research on Pulling Derivatives and Parting Wisdom

Paul Comfort and Tim Suchomel have been doing great research on pulling derivatives that don’t require a catch. Essentially, they have questioned some previously unquestioned Olympic lifting methods for athletes, such as the comparison of power cleans and clean high pulls and power output, forces during the catch (eccentric, concentric) versus forces on catching a high pull at the hip as the bar is descending, and comparing speed and power at a given percentage of a 1RM power clean and the metrics of the same load in a clean high pull.

The power clean has been a staple of training programs for athletes for more than 40 years. Valuable research has noted the athletic benefits of the power clean (vertical jumps, sprinting). However, the clean high pull appears to have greater versatility in that a wider range of force-velocity training (resulting in higher speeds and power outputs) can be performed without compromising technique.

Clearer testing parameters can also be implemented for the clean high pull, thereby making the data more reliable, and it is easier to teach and learn than the power clean by virtue of fewer steps and less complexity. If economy of time and effect is the intent, along with creating more power and speed at different intensities with a total body movement, the clean high pull just might be your movement!