The high jump is one of the most exciting events to watch in track and field. Athletes run very fast in a straight line, make a slight turn to the left or right, jump as high as they can off of one leg, and then try and contort their bodies over a bar that is only about an inch in diameter. At a high level, the event is extremely fun to watch. At all levels, it is extremely fun to coach.

The athlete competes against others but also against the bar, always trying to challenge themself and their personal best. In this article, I want to share the fundamentals of the event, as well as how we at the Jacksonville Athletic Club train for the high jump, including training ideas throughout the year.

Objectives of the High Jump

Simply put, the objective of the high jump is for the athlete to get their hips as high as possible over a fiberglass bar, without knocking it off. The high jump and pole vault events share the same objective: Jump as high as possible, in a safe manner. Like any other jumping event, having a well-rehearsed and comfortable approach is paramount to success. Much time should be spent in practice working on the full approach. I will go into this much further later on, but you should know that most success in the high jump is due to a good approach, which athletes must practice on a regular basis.

You should spend much of the time in practice working on a high jumper’s full approach. Share on XBasics of the Event

The approach: The high jump is the only jumping event where the athlete must run an approach that is not completely linear in nature. After anywhere from one to six steps in a straight line to establish speed in the approach, the athlete will then run a curved approach towards the bar in order to establish a good takeoff position from the bar. Most traditional approaches have the last five steps of the approach run around the curve. The straight part of the approach is where the athlete sets up a good acceleration pattern, and the curved part of the approach is where the athlete establishes a good lean and gets their body in an optimal position for takeoff.

The lean: One of the most important parts of the high jump approach (and therefore the high jump as a whole) is the body lean away from the bar. The curve in the approach is what takes the athlete into the pit, and the lean away from the bar (from running a good curve) is what gives the jumper time in which to bring everything UP before going IN. Since the jumper will automatically be traveling into the pit, the lean away from the bar (good space between the shoulders and the crossbar) is paramount to making sure the jumper gets all of their height before the bar. Once fully off the ground, the athlete can then just focus on rotating quickly over the bar. We try to cue our athletes to “keep their shoulders away from the bar” or simply “lean away from the bar” as they work on the curved portion of the approach.

The takeoff: It sounds simple, but if the jumper is able to run a good approach, with a good lean away from the bar (see above), then the jumper only needs to be thinking about jumping up as high as possible, straight up into the air. If the ultimate goal of this event is height, that is all that the jumper needs to be thinking about at takeoff. The curved approach will take the jumper into the pit once they become airborne, so it is jumper’s job to think about jumping straight up in the air at takeoff. Good features of a high jump takeoff include pushing off of the entire foot, driving the non-takeoff knee very fast straight up, fully extending the takeoff leg off the ground, and driving the inside shoulder (or non-takeoff leg side shoulder) straight up into the air as well.

Rotation over the bar: As we have discussed in other articles, much like a long jump landing or hollowing out the chest over the pole vault crossbar, this part of the jump is almost the “icing on the cake,” so the athlete should only work on it AFTER they’ve focused in on all the other parts of the jump. I have seen jumpers who rotate over the bar perfectly, contorting their bodies like an acrobat, but still only jump marginal heights due to their poor approaches and take-off fundamentals. A proficient approach, good lean, and aggressive vertical takeoff determine your success in the high jump so much more than good rotation over the bar.

Simply put, when the athlete feels like their hips are over the bar, they should try and press their shoulders down to the mat as fast as possible. This will allow the hips to keep rising, as well as allow the legs and feet to quickly rotate over the bar. The longer the jumper travels over the bar, the more likely they are to knock the bar off. Effective bar clearance comes from trying to rotate quickly over the bar. We tell our jumpers to try and get their shoulders down to the mat as quickly as possible.

High jump success depends on a proficient approach, good lean, and aggressive vertical takeoff. Share on XDonald Thomas is a world champion and three-time Olympian, and he goes over the bar in a very “non-ideal” position. However, he can jump over 7’9” in the high jump (one of the highest jumps in the history of the event) due to his jumping ability at takeoff. Of course, if he improved his rotation over the bar he could jump higher, but 90% of what he is able to accomplish comes from what he does on the ground.

What We Do in Training

Approach runs from full: At least one day a week, throughout the training year, we do full approach runs. In the fall training period, they might be done in tennis shoes, just to work on the rhythm and posture of the approach. From the very beginning of the training year, our jumpers work on establishing a good rhythm for their full approach run. The majority of our athletes will go from seven to 10 steps, and we will do anywhere from four to eight of these approaches at the beginning of a jump session.

Sometimes the jumper performs the approach with a modified takeoff into the pit, sometimes with a scissor jump over a bungee, and other times instead of taking off, they simply keep running around the curve and back the other way, much like a horseshoe pattern. No matter how they end the full approaches, the keys we look for are good rhythm, good body lean around the curve, and tall body position around the curve. The coach will usually watch these approach runs from the opposite side from which the jumper is running, to look at the lean away from the bar. (For example, a left-footed jumper will run towards the right standard before the curve, and the coach will stand to the side of the left standard to watch the curve and body lean.)

The keys to a good approach are good rhythm + good body lean & tall body position around the curve. Share on XScissors from full: As mentioned above, sometimes we do scissor jumps from a full, as an extension of working on the full approach. The takeoff in a scissor jump should be directed completely vertically, with the free knee (opposite leg) swinging up very quickly, and then blocking. The jumper will then simply step over (or attempt to) the bungee or bar.

Scissors from 4-6 with no mat: One drill we use that I borrowed from my mentor “Fuzz” (yes, that is real) is short approach scissor jumps, over a bar, but with no pit to land on. They go from just four to six steps, and scissor jump a bar, then (hopefully) land safely on the ground, on their feet. It is so much easier to jump into the bar when you know that you will land on a big, comfortable, mat. When you take the mat away, the jumper will only jump into the bar once—they won’t like the sensation of landing hard on the track, and will self-correct on the next few jumps. This drill, if done in a safe manner, can be very helpful in teaching a good lean away at takeoff, and then a complete vertical jump at takeoff.

Jump from 6: Most of our high jumping in practice is from a short approach. We do a lot of jumps from six steps, as the jumper can still bring some speed into the jump, as well as take a lot of jumps without tiring out too quickly. We look for the same fundamentals that we would from a full approach: good speed, good lean around the curve, staying tall throughout the curve, and a takeoff that is vertical in nature. We also try to watch from the side opposite to where the athlete jumps from, so that we can see the shoulders away from the bar at takeoff, and see the inside shoulder and knee drive up fully before going back into the mat.

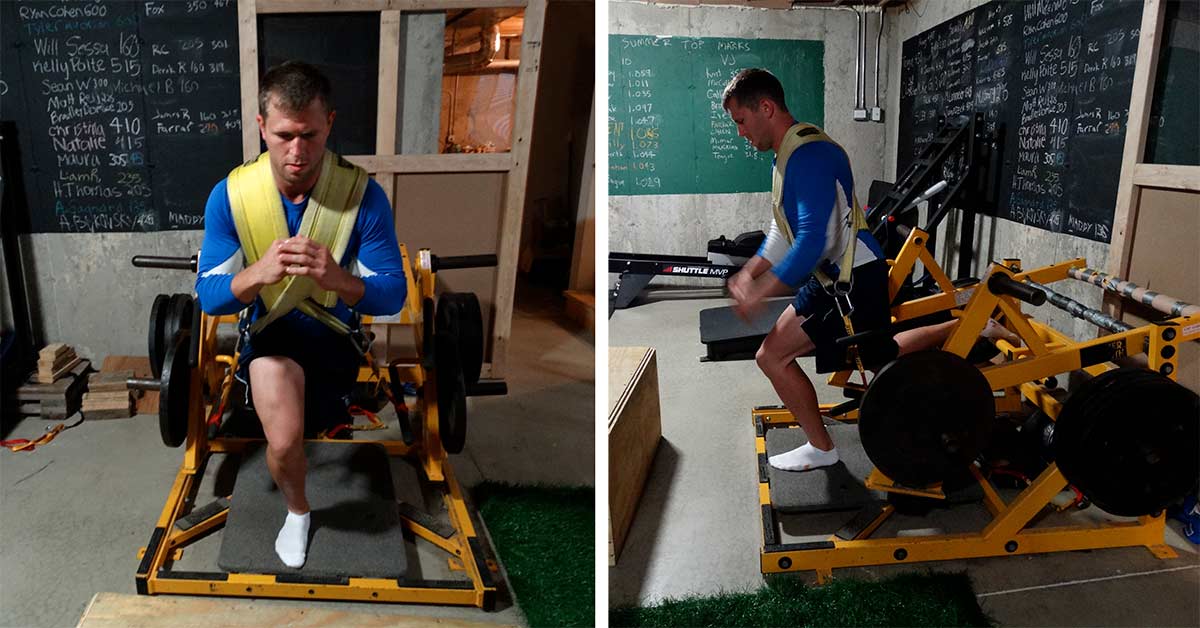

Jump from 6 off ramp: Want to know a way to give your high jumper even more jumps in practice, more time in the air, and more confidence? For $99.95, you can learn this one special trick the experts don’t want you to know! Or you can just keep on reading…

One of the drills our athletes love to do is jump from six steps off an elevated ramp. The ramp we have is about 6 inches high and is large enough that if a jumper has a bad approach, they can still jump off it and not worry about breaking their ankle (that would be bad). Athletes really like jumping off the ramp for one simple reason: They can jump really high off the ramp. That makes the activity fun for the athlete, and one they enjoy working on.

We like to start off pretty low, then go up in 3-6 inch increments, with the goal of getting the jumper to extend off the ramp longer and longer to keep jumping at the bungee. If a female jumper who has a PR of 5’ starts with the bungee at 5’ from six steps off the ramp, she should have no problem jumping at that height. However, if you keep the bungee there, the jumper will get used to jumping high enough to clear the bungee, but then not much higher.

Moving the bungee up forces the jumper to put more pressure into the takeoff and to extend more at the takeoff, to try to have a good attempt at the higher bungee. We have had athletes jump off the ramp at heights that were almost 2 feet over their current PR. Did they come close to clearing the bungee? Of course not. But the goal of this drill, and the reason it is so much fun for the athlete, is to try to jump as high as possible. This is so much easier if they have something really high to jump towards.

The main reason we jump from six off the ramp is simply to jump at high bungees, to get the athlete used to jumping high at takeoff. We also jump from six off the ramp to work on rotation over the bar, as well as having competitions over a bar.

To work on rotation over the bar, we put the bar up around the athlete’s PR, and have them jump off the ramp (which gives them more time in the air) and work on rotating over the bar properly. The goal is now to work on what they do over the bar, and not so much how high they can jump. We will usually do this eight to 10 times, leaving the bar at a manageable height, so that they don’t have to worry so much about the takeoff, but rather think more about rotating fast over the bar.

The final exercise we do off the ramp from six steps is to compete in one jump over a bar to try to set a new six-step ramp PR. We have club records for this activity, and it is a lot of fun to have the athletes compete against themselves, each other, and past club members. So, you can have your athletes do this “simple” exercise of jumping from six steps off the ramp to try and accomplish different goals: jumping up as high as possible, working on rotation over the bar, and working on bar clearance at higher heights. I have yet to work with a jumper who didn’t enjoy this drill, and this is usually the one activity we do the most on jump days.

Jump from 4: Early on in the year (fall period), we jump off the ground and off the ramp from four total steps. The same principles apply here, with just a shorter approach. From this short approach, we usually put a bar to work on rotation over the bar, but at a height that is not too challenging for the athlete.

No “back over” work: The only time we do “back over” work is when we are teaching a complete beginner how to high jump. A lot of time is wasted in high jump training doing back flops and all sorts of cool-looking “Matrix”-type moves in the air, when in reality what matters most is a good lean and takeoff. If you do these things correctly, the rotation over the bar becomes much easier.

Bungee vs. bar: In our training, we mostly high jump with bungees, due to the fact that we have a lot of athletes jumping at one time. If we want to work on rotation work over the bar (from a run), we will have the jumper jump over a lower bar, to work on some of the rotation mechanics in the air. I have found that much like Pavlov’s dog, athletes have been conditioned to equate the bar falling off with failure. They could have done a great job with the approach, and done something minuscule over the bar to cause it to fall, but as soon as a jumper knocks a bar off their first thought/instinct is one of failure.

I find that athletes equate the bar falling with failure, even if they did everything else right. Share on XThe vertical jumps can be very mental, so we try to make training as much of a positive environment as we can. I know other coaches who only use bars in practice, and they have had a lot of success as well doing it that way. It is up to you to do what works best for your system and your athletes. I have just found it to be better in our group to use the bungee more than the bar in training.

Practice Ideas Throughout the Year

While a complete training schedule for the high jump is beyond the scope of this article (you can find a detailed training plan in our articles on training for the jumps, as well for the combined events), I did want to mention that we train all of our high jumpers as either combined event athletes (heptathletes and decathletes) or as jumpers who are able to do the horizontal jumps as well.

A better overall athlete becomes a better high jumper, so we work really hard at getting our jumpers faster, stronger, and more coordinated, and this has carried over very well into the development in their high jumping ability. Our high jumpers will usually high jump one to two days a week, and work on speed, power, coordination, as well as general strength development on the other days.

Final Thoughts

The high jump is one event where we have had a lot of success over the past few years, and I believe this is due to how we teach the event, and how we train our high jumpers to be better athletes first, and then focus on the “high jump stuff.” We have found drills and exercises that work, and we are able to have our athletes buy into our system of teaching the high jump. Most of the success comes from the athlete wanting to get better, doing what is necessary, and trusting the program.

We train our high jumpers to be better athletes first, and then focus on the “high jump stuff.” Share on XThis event is not rocket science (although it has the closest resemblance to such study, as both are trying to put a body in flight…), but HOW you teach and coach it can make a huge impact on the athlete’s success in the event. If you want your athletes to jump high in meets, they need to jump high in practice. Off a ramp, attempting really high heights over a bungee, or jumping high bars from a short approach all help accomplish this goal.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following coaches and mentors for all of their wisdom and guidance as I learned how to coach the high jump better: Glenn McAtee, Dr. Drew Hardyk, Fuzz Ahmed, Robert Olesen, Boo Schexnayder, Noel Ruebel, and Clark Humphries. All of you have taught me so much, and all of the improvements we have had in this event are a reflection of your knowledge and insight, so thank you again!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF