[mashshare]

The multi events in track & field—which consist of the decathlon, heptathlon, and pentathlon—provide coaches and athletes with a unique set of circumstances. The events require a multitude of physical and technical skill sets. The coach must balance the athlete’s training components to best enable the individual to develop across a broader physical and mental spectrum than that of single event athletes. Managing the physiological, psychological, technical, and tactical requirements is no easy task.

In this article, we aim to simplify some important aspects of multi event development. We will discuss how to plan long-term training, advice on meet selection, psychological preparation, and more. Our recommendations come from years of study and experience within track & field, sport performance, and strength & conditioning.

Recommendations for Event Groupings

The number of events required for a multi eventer necessitates careful consideration from the coach and support staff. The physical, mental, and logistical constraints of a session and training cycle require the coach to maximize the efficiency of each programmed workout. There are various ways to consider this issue, and for a more in-depth rationale, please refer to How to Program for Multiple Events.

Four recommended approaches to event groupings are:

Event Sequencing Based on Competition Scenarios

You can utilize meet modeling with great success when preparing athletes for competition. It can help ingrain the rhythmic change that a heptathlete experiences when moving from the hurdles to the high jump. Psychological shifts are also required throughout competition, for example when a decathlete races the 400m dash after the high jump competition. This becomes an easier shift if the athlete has performed equivalent sessions where speed endurance workouts followed high jump sessions. This philosophy extends beyond a single session, as multi-event athletes must also be able to compete at a high level on consecutive days. Thus, programming back-to-back high intensity days can prepare the athlete to handle such requirements.

Time Program-Based Grouping

If you’re a track coach, you can essentially reduce time programs to ground contact times (GCTs). The longer definition is that a time program is a movement-specific innervation pattern determined by both the neuromuscular impulse sequence of muscle activation and the behavior of electrical activity—the quantitative expression of a fundamental movement program, such as the GCT of a depth jump. By pairing similar time programs within the same training session, the athlete’s central nervous system (CNS) will receive robust yet concise messages to enable a transfer among structurally similar movements. Generally, a shorter GCT will result in a more-effective time program and one of the fundamental prerequisites to running fast or jumping far is applying great force within a minimal time frame.

For categorizing GCTs, ~200ms serves as a useful inflection point. Anything faster, such as a hurdle hop or sprint, is an elastic, high-speed movement that serves to train the athlete more on the velocity side of the force-velocity curve. Any power-based movements slower than 200ms, such as a box jump or Olympic lift, are better suited for training the force side of the force-velocity curve. Thus, it follows to pair track work by these time programs. For example, high jump take-offs and foot strikes during an athlete’s acceleration phase have similar time programs, so HJ-Accel sessions are effective. Likewise, max velocity work (such as overspeed running) matches up well with an exercise like depth jumps.

Pair by Rhythm and Technique

Construct practices to focus on certain rhythmic and technical similarities between events. Performing events in this manner can help reinforce commonalities among them. In terms of technical similarities, one approach is to link events by the nature of their firing patterns (horizontal vs. vertical). For rhythm matchings, working on high jump and javelin in the same session can enhance efficiency since those events share similar body postures and approach cadences. Grouping using this rationale is particularly effective when technical variances are high or the athlete is developing new technical patterns.

Grouping by Metabolic Demands

Organizing sessions by metabolic demand enables the coach to adhere to a sensibly balanced program. Under such a setup, an athlete can stress contrasting energy systems over the course of several days. The three areas that multi-event athletes must touch upon are the alactic, glycolytic, and aerobic energy systems.

The alactic anaerobic (i.e., phosphate) system is the first energy system we use. It is the muscles’ dominant energy source for roughly the first 10 seconds of high-intensity exertion. Next, the glycolytic (i.e., lactic) energy system takes over. This contributes most of the energy for as long as 90 seconds of activity. After a sustained bout of high-intensity exercise beyond 1.5-2 minutes, the aerobic system contributes the most energy. For example, a decathlete could stress the alactic energy system on Monday (e.g., 3x3x20m heavy sleds (3’/8’) followed by deep squats). While this athlete will be fatigued the following day(s), he or she is still able to stress the contrasting aerobic energy system (e.g., 8x200m at 65% (2’)) with minimal interference.

One caveat to this we have seen and used is the performance of a high-intensity neural session, such as the heavy sled sprints, immediately followed by a seemingly contradictory session, such as a quick bodyweight circuit. The theory behind this is that the latter will help expedite the athlete’s recovery process from the former by increasing blood flow and the athlete’s hormonal profile.

Recommendations for Competition and Event Selection

The nature of multi-event competitions necessitates that athletes rarely compete in the multi events, compared to their open event peers. A multi-event competition is far superior in terms of physical and mental demands than most other events, which limits the frequency to championship meets and regular season meets used for qualifying purposes. Thus, you can view all preceding meets as highly specific, glorified practices to use as meet preparation for the multi events. Approaching competitions from this perspective allows the coach and athlete to prepare for and gauge performances in the appropriate context.

Here are five recommendations to keep in mind when preparing an athlete’s competition schedule:

Within the meet, the athlete should hurdle, select one jump and one throw, and/or sprint. While the exact combination of events is constrained by the meet schedule, entry limits, and entry standards, this allows the athlete to perform high-quality repetitions in a variety of disciplines. Ideally, the athlete will rotate between the jumps (long jump, high jump, pole vault) and the throws (shot put, javelin, discus) from meet to meet. Balancing these event types will prepare the athlete to utilize different energy systems, techniques, and rhythms in the same competition.

The overall load of the meet will depend on the time of year and current training cycle, but it shouldn’t overload the athlete. The coach needs to note height progressions, whether the meet has finals for sprints/hurdles, and if there are three, four, or possibly six attempts in each throw and jump, and adjust accordingly with contingency plans.

(Almost) always hurdle. If possible, the athlete should hurdle at most meets. The hurdles is a unique event in that success is so heavily dependent on rhythm (not that rhythm doesn’t play a huge factor in other events!), and it is hard to replicate all of the sensory variables and physiological characteristics that accompany competition outside of this specific setting. Additionally, use hurdles as an event to touch on qualities that are useful in the other events. The race requires an acceleration phase; is plyometric in nature; incorporates coordination, steering, and timing in its movements; and can even broach some speed endurance work in the outdoor races.

(Almost) always pole vault. Similarly, it is advisable to compete in the pole vault when possible. Not only is pole vault a highly technical event, but it is often hard to achieve the necessary practice time. This is especially true in areas with less-than-ideal weather, no access to an indoor facility, or limited access to a pole vault coach. The heightened stress of practicing the event in meets should pay off during the later multi-event competitions, where every bar (10-centimeter increments) is worth just under 30 points.

So, while decathletes should be rotating between the jump events, the athlete and coach should capitalize on meets where pole vault heights are appropriate for the athlete. Heptathletes can apply this strategy to high jump. The high jump is another event with unique technical demands where a clearance at bar X has compounding importance—not only does it guarantee you roughly 35 additional points for each 3-centimeter improvement, but it enables further attempts at higher heights.

Be cognizant of the point values attached to each event. While a balance of event work is necessary for any successful multi-event athlete, the coach must realize where his or her athlete can make the largest point gains. The running events (sprints, hurdles, 800/1500) and jumping events present the greatest opportunity for overall point increases. Thus, since we have established that you can view these meets as glorified practices for the multi-event athlete, it only makes sense to place an emphasis on the more important events from a points perspective.

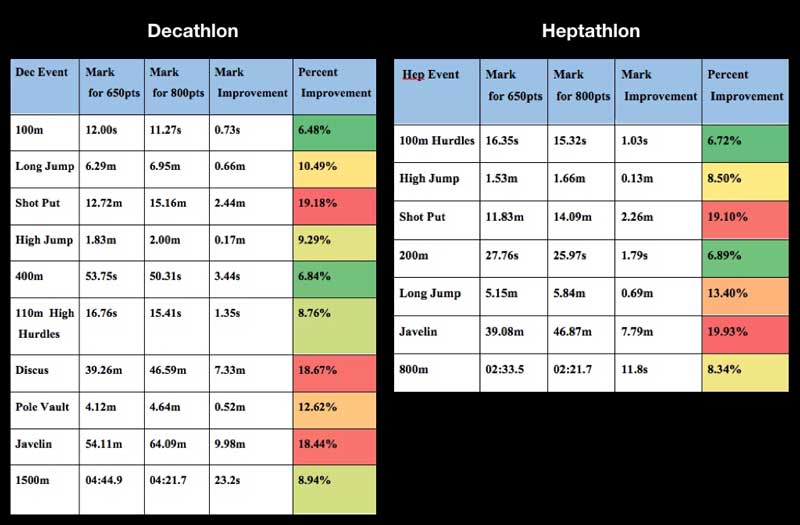

For example, if there’s a meet conflict between the long jump and javelin, the athlete should almost always prioritize the long jump. This is, of course, subject to change if the goal of the meet is to work on javelin, but this philosophy generally holds true. The tables in Image 1 illustrate the various difficulties of improving by 150 points in each event. While this is a slightly reductive approach to comparing events because it does not account for the potential of technical improvement and physiological limitations, it is helpful for assigning baseline importance to each event.

Decathletes should race a 400 before competing in a decathlon. It is important for a decathlete to race a 400, either open or in a relay, before his or her first decathlon. This also applies, although to a lesser extent, to heptathletes and the 200. There is usually a large improvement from the first 400m of the season to the second, so it would be reckless to concede that point differential. Moreover, the athlete will most likely recover better for Day 2 of the multi event than he or she would have without this first race. This is irrespective of the amount of special endurance or speed endurance work included in the training load.

Recommendations for Psychological Preparation

The multi events present a unique and particularly difficult challenge for competitors. The psychological demands are complex and are evident not only during competition but also the day-to-day requirements of training and recovery.

The physical and psychological energy of a multi-event athlete must be monitored frequently. Share on XMulti-event training requires longer duration and more frequent training sessions across a broad range of physical and technical skill sets. These can differ in mental preparation due to the variance in technical complexity, arousal and focus requirements, and overall enjoyment relative to the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses. Both physical and psychological energy must be distributed carefully across these tasks and monitored frequently.

The competition setting requires even greater psychological strength. With five, seven, or 10 events, and multiple attempts during many of them, the possibility of adversity and disappointment is very high. The management of expectations and goals is an ongoing process strongly linked to psychological preparation.

Here are four recommendations for the psychological preparation of multi-event athletes:

Psychological adaptability—the ability to re-evaluate, re-focus, and re-energize almost instantaneously—is an essential attribute of a multi-event athlete. Planning open event competitions with this in mind can pay dividends later. While we already touched on the physical benefits these competitions can provide, you can also use them to your advantage from a psychological perspective. For example, competitions where the athlete is competing in two to three events with slightly overlapping or conflicting schedules help develop efficiency, focus, timing, and organization. Balancing these suboptimal competitions with more ideal scenarios (focusing on the athlete’s event strengths under ideal conditions) will simultaneously enhance confidence and adaptability.

Intentionally frustrating sessions can be useful. Although you should design the majority of training setups for optimal physical and technical development, it is advisable to include confusion- or frustration-style sessions into the program. Ideally, issue these sessions closer to the competition period, after the athlete has achieved a high standard of specific fitness and technical proficiency. Examples include sessions where technical event sequencing is suboptimal or using drill variations that are new or unpracticed.

Creating certain technical or outcome problems with minimal coaching feedback is also important. It could be a third and final long jump attempt with fouls on the first two attempts, or random hurdle heights and spacing. Other examples include making approach adjustments on the fly from random starting positions in the jumping events. These sessions require great focus and adaptability because the athlete cannot simply rely on physical abilities to achieve a desired result.

Athletes should be ready to implement proven, personal coping strategies. As the above examples suggest, acclimating to certain stressors inevitably helps you deal with them. However, along with having experience to fall back on, it is important to have personal tools and strategies to call upon when needed. It is beneficial to group relaxation and visualization strategies together, as they are also often part of an established routine.

Each athlete must develop “their safe space” during practice and competition settings. This is a time away from their coach and competitors during practice and competitions where they breathe, focus, visualize, and relax. Typically, this occurs after an attempt or race, and after the coach-athlete feedback is complete.

We can help establish a routine for each athlete, but it’s more important that athletes establish one for themselves. The most important aspect of this is buy-in and trust. Creating a culture of self-reflection and spiritual connection to the process early in the coach-athlete relationship helps manifest this.

Play to the athlete’s mental strengths, not just his or her physical strengths. Multi-event athletes will almost always have at least one standout event. This event is where the athlete’s confidence is highest and is often the one he or she enjoys the most. Success in this event promotes high self-worth and can enhance important psychological attributes needed for weaker events.

It is common to forget about these events during preparation competitions for the main multi-event competition of the year. Although competitions focused on highly technical or weaker event selections are important, plan certain meet and event schedules to enable confidence to peak alongside physical and technical shape. Adjusting the ratio of weaker and stronger event selections within individual competitions can be an excellent way of psychologically preparing the athlete for their peak.

Recommendations for Multi-Meet Management

After successful preparation in practice and the open meets leading up to the multi-event competition, it is paramount that the coach and athlete successfully manage this competition to capitalize on all of the hard work.

Here are five of our recommendations for managing a multi-event competition:

Set up pre-meet stimulation one or two days before competition. The two days preceding the start of competition should consist of a recovery day, as well as a stimulation (stim) day to freshen up the CNS. Either sequence (Recovery-Stim or Stim-Recovery) can work if you plan the overall setup appropriately. For example, the athlete could do a long, slow warmup followed by easy build-ups on grass two days out, and then a more dynamic warmup followed by light hurdle hops and block starts the day before competition. Reversing this schedule can also work, so it is important that the coach understand what works best for each of his or her athletes.

The mental aspect within competition is everything. Beyond the points already covered about psychological preparation, there are additional factors to consider that are unique to the competition setting of the actual multi event. The few multi events each year are usually extremely high pressure competitions, as they are either championship meets or knowingly used to qualify for such meets. After each event, allow the athlete a couple of minutes to feel happy, mad, sad, frustrated, or any other emotion about the result. It is unrealistic to expect the athlete to flip a switch, so allowing the athlete to vent will be beneficial. However, once this time is up, the athlete should completely focus on the upcoming event and let the coach worry about point totals. The athlete should be confident in his or her preparation going into the competition, so his or her only job is to compete in each event.

Staying relaxed between days is crucial. Between events, and especially between days, the athlete should stay loose and have fun. Engaging in other easy activities between days, such as watching a movie, will help keep the athlete’s mind from wandering to a stressful place. Ideally, the athlete will compete with at least one teammate, as a positive dynamic there can go a long way towards enhancing the overall experience. It is important for the athlete to try not to stress about point totals, particularly between competition days—having the multi-event calculators online certainly complicates this. Nonetheless, it is important for the coach and athlete to have a quick debrief after Day 1 and review what the mission is for Day 2.

The athlete and coach should have a physical protocol to follow for the meet. This includes an established pattern for morning stim, event warmups, and recovery in between days. It is advisable to perform some form of light stimulation on the morning of the meet to help the athlete wake up his or her CNS. This can include dumbbell snatches, med ball throws, or even light jumps in a hotel stairwell, and should occur at least two to three hours before competition.

This routine is perhaps even more important on Day 2, when the athlete is tired and sluggish but needs to be ready again after the first event. For each event, the athlete and coach should have a rough idea of the ideal number of starts/run-throughs/pop-ups/throws to perform, and obviously make adjustments depending upon how the athlete looks and feels. The goal of the event warmup is to maximize the outcome of each event, not to worry about overexerting the athlete—the athlete will be well-prepared through training to handle the load of a multi-event competition!

Meet nutrition should be regimented and worry-free. The athletes should eat their normal breakfast (which is, ideally, healthy). Following the second event of Day 1, athletes should make a point of eating “real food,” such as a turkey sandwich. This comes after high jump for the women and long jump for the men. For each of them, it will be before warming up for shot put, giving them plenty of time to digest before the fourth event of the day.

For Day 2, decathletes should plan on eating a sandwich after hurdles, discus, and/or pole vault (this is very much athlete-dependent) Heptathletes should eat after long jump on Day 1 and before javelin, so that they are energized going into the 800. Throughout the meet, athletes should have easily digestible snacks on hand (fruit, crackers, bars) and pump fluids throughout the day. You may have to remind the athletes to eat, as the stress of competition and adrenaline take over.

Recommendations for Training Organization

Training organization needs to be simultaneously approached from the perspective of multiple pieces. The coach must be cognizant of not just the event groupings within a training session, but also how the training cycles compound on each other throughout the year with the end goal in mind, as well as how the various facets of training (strength training, mental preparation, technique work, etc.) interact. You can approach programming from the perspective of broad to narrow, as understanding the larger principles at work provides the essential basis for successful daily sessions.

Here are three recommendations for addressing the organization of training for multi-event athletes:

Stress technical development all season long, albeit to varying degrees. Technical development should follow a general to specific progression, stressing fundamentals and skill acquisition. The coach and athlete should select the most important exercises and best training methods for the athlete’s talent level and position on the continuum of technical proficiency. For the multi-event athlete, losing contact with any event for a prolonged period will sink his or her overall score. Thus, even during the General Preparation Period (GPP) or earlier, we recommend incorporating elemental exercises that will later transfer for the athlete.

For example, performing rotational medicine ball throws can serve as a core training and general strength exercise, while also keeping the athlete in tune with the rhythms and patterns of the throwing events. This requires more nuanced scrutiny from the multi-event coach, particularly those who coach at the collegiate level and must focus on both the indoor and outdoor seasons. Following the throwing event example, the shot put is a component of both the indoor and outdoor multi events, whereas javelin and discus are only scored outdoors. Therefore, the coach could justify progressing the shot put at a faster rate than the other throws, since his or her athlete will already be throwing shot put for points at a conference championship meet in February or March, while discus and javelin won’t factor into point total until April or May.

Preparatory training phases should also follow this progression of increasing intensity. While the goal of most sessions is the highest-quality speed and power expression, the athlete must carefully progress in order to handle consistently high training loads. From an annual perspective, this starts with the athlete undergoing, in some fashion, a GPP to begin to acclimate the body for the increased demands of more event-specific work later in the year. Taking a further step back, the coach must also assess the athlete’s overall training age. Elite athletes who have a higher cumulative training base will require less work in the traditional GPP mold to progress. It is important to think in terms of emphasis shifts rather than rigidly focused training blocks. Done correctly, emphasis shifts provide seamless transitions throughout the year.

Strength training must be programmed in conjunction with the overall training plan to serve as a complementary component. As the season progresses, the goal of weight room work shifts from maximum strength work throughout deep ranges of motion to more event-specific joint angles and speed and power expression. The back squat, for instance, can progress from deep squats utilizing the full range of motion for maximum muscle fiber recruitment and basic strength development to explosive quarter squats that more accurately mimic the firing patterns utilized during jumping events. However, you should maintain max strength work throughout the competitive season—you can preserve, or even enhance, it with just a single session every 10-14 days.

Adjust strength training depending upon the athlete’s training experience, like annual training cycles are. Less-developed athletes will respond well to basic strength work touching along all points of the force-velocity curve. However, more-developed athletes may require the additional stimulus of potentiation complexes in the weight room to spur improvement. This can be performing back squats to potentiate vertical jumps or alternating weighted bounding with unweighted bounding.

Two Successful Sample SPP/Peaking Cycles

Here, we provide sample training programs that we successfully implemented at our respective schools, Johns Hopkins University and the University of California, Berkeley. At Johns Hopkins, senior Andrew Bartnett finished as the Division III National Runner-Up in his first season competing in the heptathlon, with a NCAA D3 #6 All-Time score (5,238 points). At Cal, sophomore Tyler Brendel finished the outdoor season with a decathlon score of 7,413 points, an improvement of over 400 points from his freshman year and good for No. 8 All-Time in school history.

We feel these samples provide a helpful illustration for implementing the philosophies discussed above, while also accounting for the practical constraints of working with our student-athletes.

Although Bartnett was a senior, he spent the first 2.5 years of his collegiate career purely as a pole vaulter, so many of the technical drills were more remedial than you might expect for a senior multi-eventer. Additionally, Bartnett was a mechanical engineering major with a very intense “Senior Design” practical course for an external company run through JHU, which required careful monitoring of his sleep and recovery habits. Consequently, it was common for me and him to alter the intensity and density of his workout plans to accommodate his greater development as a person and student—the purpose of intercollegiate athletics.

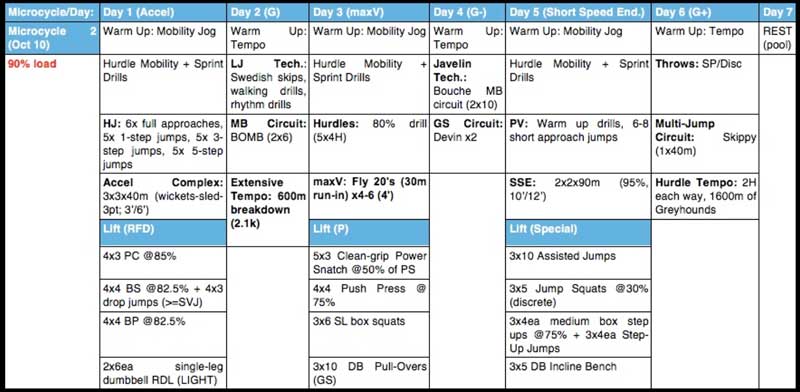

The first Specific Preparation Period (SPP1) at Johns Hopkins during the Fall 2016 training period used the following microcycle. This was the second week of a three-week cycle that utilized an 80-90-50% training load pattern, so this was a very demanding week that built on the previous week and then led into an unload week for the athletes. As a whole, this SPP was a progression from the four-week General Preparation Period where we laid the groundwork for the more intense sessions you see here. The main goals of this cycle were to continue our technical progressions within each event, touch on max strength (MxS) and rate of force development (RFD) in the weight room, and begin to advance high-effort max velocity and short speed endurance capabilities.

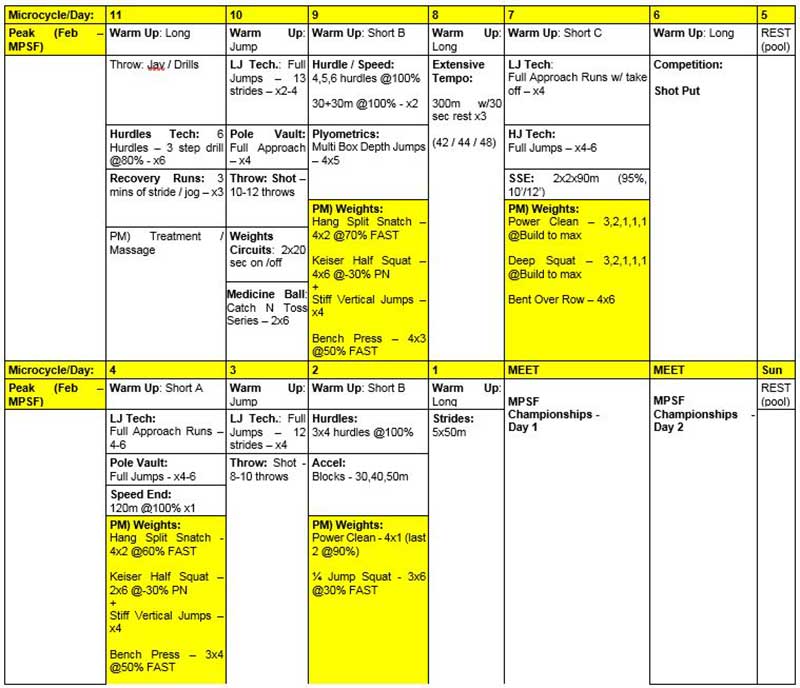

The mesocycle shown in Image 3 was the final two weeks leading toward the 2017 indoor Mountain Pacific Sports Federation Championships (“MPSFs”). Brendel’s performance during the competition was superb, as he totaled seven personal bests across the two-day competition. It was particularly pleasing for me—and a reason for choosing to highlight these two weeks—to see his significant improvements during the two days compared with the previous month of competitions. Our training load remained relatively high until the final two-week taper began, and even then, you can see that the taper isn’t particularly aggressive. We maintained a reasonably normal workload until three to four days prior to the competition for a couple of reasons.

First, we have a very short indoor season at Cal, with only two meets before our indoor championships. As a result, we operated on a reduced training load for four weeks leading up to the MPSFs. A further reduction in load could have adversely affected performance during the championships.

The second reason is that it is important to always consider individual tapering strategies, and one of the most influential aspects of this taper was the athlete himself. Brendel had a considerably high work capacity and a meticulous approach toward training. He rarely missed a session of any kind and over the preceding five-month period had developed an outstanding level of general and specific fitness. It was important for him to maintain a consistent and frequent training regime to avoid physical and psychological detraining.

We will now discuss details of the two-week plan. Our typical setup during non-competition weeks is a High/ Med/ High/ Low/ High/ Med/ Low loading pattern across seven days. This final mesocycle included setup alterations that allowed training intensity to gradually increase for the first two days. This gave Brendel recovery from the previous two-week cycle and allowed for his sharpest work. Throughout the remainder of the taper, readiness and performance levels increased gradually. This was clearly evident during each subsequent session of the taper.

Specificity was, of course, very high at this stage and almost all the work performed was at 90% or greater of meet performance capabilities. The weight training session with seven days remaining was an important one: Seven to 10 days before a major competition, I implement the final RFD and MxS session. The remaining weight training sessions are used to sharpen up and focus on velocity (this can change with certain athletes).

The final week involved more event-specific touchups, with a considerable drop in load beginning four days from the start of the competition. All aspects of Brendel’s velocity were very high during this week and he was the sharpest I had seen him. With four days remaining until the Championship, it was all about confidence and intensity. Then, he was ready.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article and will consider some of the suggestions we propose. If you found this article informative, please share so that others may benefit as well.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

Authors

Nick Newman, MS:

Nick is an Assistant Track & Field coach at the University of California, Berkeley, where he oversees the jumps and multi events. During his first year with the Golden Bears, his athletes achieved 32 personal records, and earned two podium finishes during the outdoor PAC12 Championships. Before joining UC Berkeley, Nick dedicated 10 years to the study and application of the development of athletes ranging from pre-adolescent youth to the professional ranks. He earned his bachelor’s degree in Exercise Science from Manhattan College and later earned a master’s in Human Performance and Sport Psychology from California State University, Fullerton. In 2012, Nick published his highly acclaimed book, The Horizontal Jumps: Planning for Long Term Development. Nick is a certified strength and conditioning coach, a certified track and field technical coach with the USTFCCCA, and a sports performance coach with USA Weightlifting.