Quinn Henoch is a Doctor of Physical Therapy who is often praised for bridging two worlds often seen as separate: strength and conditioning and physical rehabilitation. Dr. Henoch is the head of rehabilitation for JuggernautHQ and Darkside Strength, and he has a clinic, Paradigm Performance Therapy, in Laguna Niguel, California.

Dr. Henoch received his Ph.D. in Physical Therapy from the University of Indianapolis and his B.S. in Kinesiology and Exercise Science from Valparaiso University. He specializes in reducing an athlete’s risk of injury and returning them from injury as quickly as possible. Henoch is a writer and speaker who produces content geared toward bringing awareness to the importance of a symbiotic relationship between strength coaches and physical therapists.

Quinn shares his unique perspective as a strength coach and PT in this episode. He answers many common questions that physical preparation professionals might have due to the flood of corrective exercise and SMR tools available to us and our athletes today. He discusses static stretching, foam rolling, and many other topics relating to his expertise.

In this podcast, Dr. Quinn Henoch discusses with Joel:

- Quantification of the term “good movements.”

- The relationship between flexibility and strength.

- Athletes having a surplus range of motion, and its consequences.

- Setting expectations with athletes and patients.

- Using infant patterning for athletes.

- Effective uses of breathing in a training setting.

Podcast total run time is 58:15.

You can find Quinn at JTS and Clinical Athlete.

Keywords: mobility, physical therapy, breathing, strength training

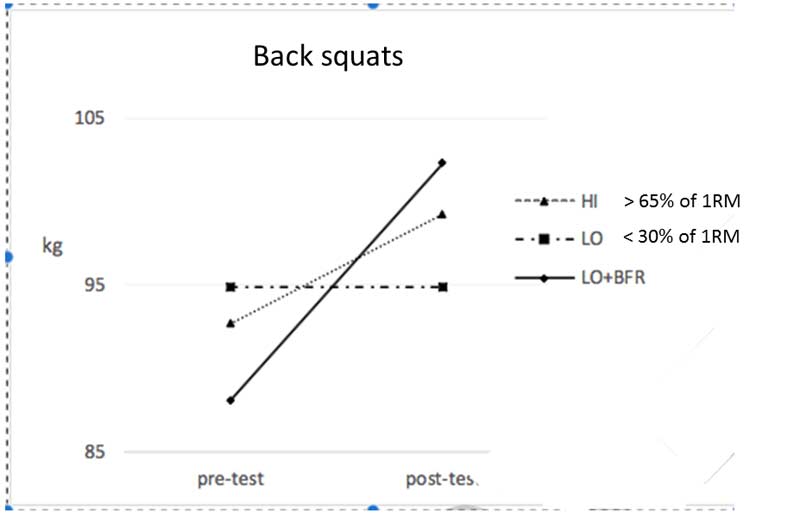

Originally from San Francisco, CA a graduate from San Jose State University with a B.S. in Kinesiology, Eric Bringas received his M.S. in Applied Exercise Physiology from Concordia University Chicago. While completing his Capstone, Bringas was involved in many academic projects that focused on Blood Flow Restriction training. In conjunction with his academic endeavors, while working at Arthur J. Ting, M.D. Orthopaedic Surgery & Sports Medicine Center, Bringas worked as an Head Exercise Physiology Specialists to the Directors of Rehabilitation John Murray and Dr. Ting. Dr. Ting’s Surgery & Sports Medicine Center was one of the first programs to incorporate Blood Flow Restriction Training.

Originally from San Francisco, CA a graduate from San Jose State University with a B.S. in Kinesiology, Eric Bringas received his M.S. in Applied Exercise Physiology from Concordia University Chicago. While completing his Capstone, Bringas was involved in many academic projects that focused on Blood Flow Restriction training. In conjunction with his academic endeavors, while working at Arthur J. Ting, M.D. Orthopaedic Surgery & Sports Medicine Center, Bringas worked as an Head Exercise Physiology Specialists to the Directors of Rehabilitation John Murray and Dr. Ting. Dr. Ting’s Surgery & Sports Medicine Center was one of the first programs to incorporate Blood Flow Restriction Training.