Scott Salwasser is the Assistant Director of Strength and Conditioning for Football at the University of South Carolina (an update from his position when he recorded the Episode 1 podcast). He came to South Carolina from Texas State, where he was the Head of Strength and Conditioning for Football. Before that, Salwasser had a successful run as the Director of Speed and Power at Texas Tech University. He also served as an assistant strength and conditioning coach at UC Berkeley in Santa Clara CA.

Coach Salwasser completed an M.S. in Kinesiology at UC-Sacramento in 2006. He has an extensive background of success in the area of speed and energy system development for American football athletes. Salwasser holds certifications in Strength & Conditioning from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (CSCS) and from the Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association (CSCCa).

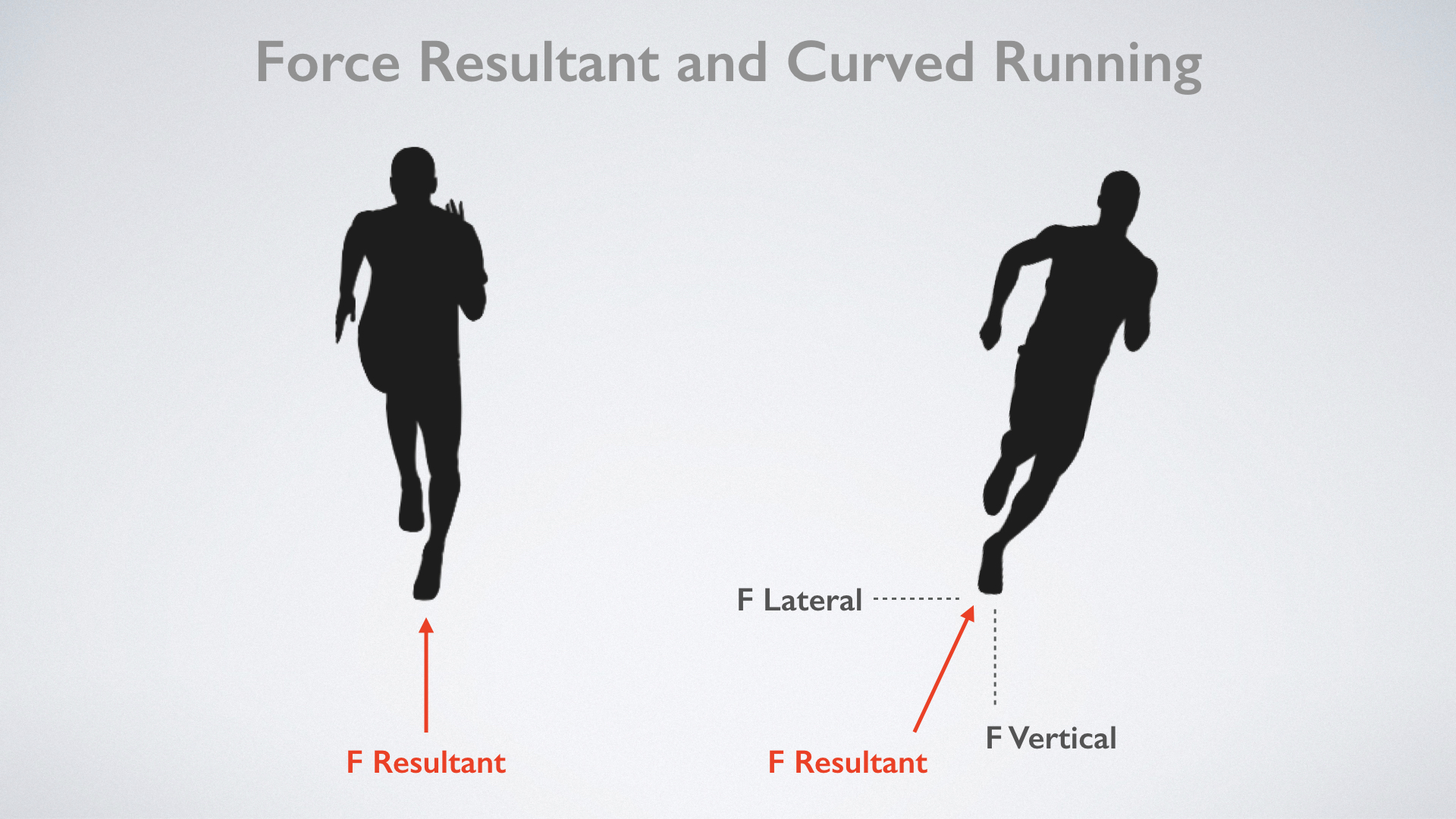

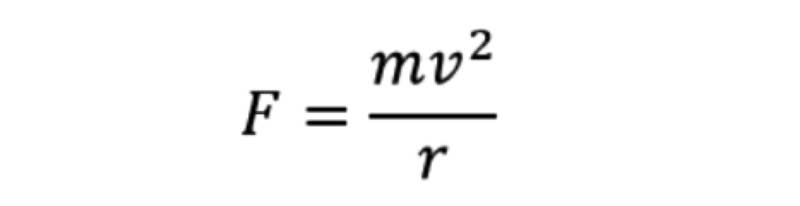

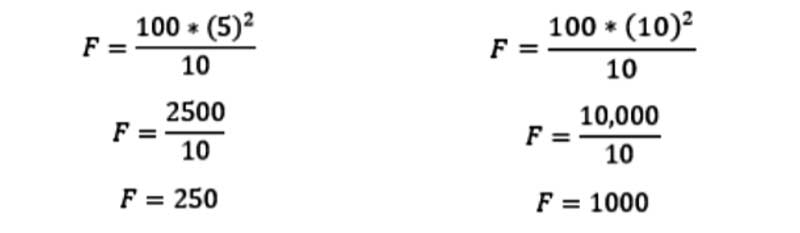

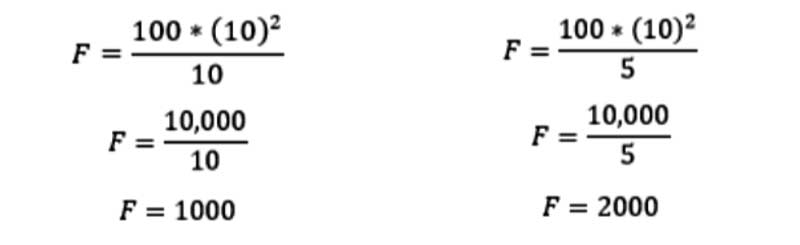

Scott breaks down his philosophies on force and what that means in the sport of American football. He discusses his utilization of heavy sled training and force-velocity profiling. He explains how to create training that yields better transfer to the field of play by using open-ended versus canned drills.

In this podcast, Coach Scott Salwasser and Joel discuss:

- Scott’s most recent revelations on speed performance.

- Training strength without compromising the athlete’s movement patterns.

- The use of force-velocity profiling and weight room applications.

- The use of heavy sled training in-season.

- Creation of open-chain patterns to improve in-game abilities.

- Individualizing training using positional specific demands.

Podcast total run time is 1:07:37.

Keywords: force, force-velocity profile, football speed, sled pulling