Nicole Foley is an assistant coach of East Coast Gold Weightlifting, one of the most decorated and renowned national teams in the country. Inside of ECG headquarters, she has developed and grown a youth/junior weightlifting program, and she is the Events Coordinator and Meet Director. Coach Foley is also the Co-Founder of Rude-Rock Strength and Conditioning and works as an independent contractor out of the Iron Asylum (Virginia Beach, VA), where she is a strength coach and the resident Olympic Weightlifting coach. Nicole is the Social Media/Marketing Coordinator for East Coast Gold Weightlifting and several other exercise-based companies.

Nicole received her BA in Dance and Corporate Communications from James Madison University and her MS Ed. in Sport Management from Old Dominion University. From 2015–2019 she was the Head Coach of the Old Dominion University Dynasty Dance Team, capping off a 15-year career as a dance coach and instructor. She is recognized through the NSCA as a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist. Through USA Weightlifting she has received her Advanced Sport Performance certification and has coached athletes at the national level.

Freelap USA: You have a solid background in weightlifting and coach those lifts with some of your clients. Due to your passion for the sport, how do you manage your natural bias (the one we all have as humans)? Do coaches sometimes overcompensate and not use the lifts at all for fear they will appear biased?

Nicole Foley: Splitting my time as an Olympic weightlifting coach, a strength and conditioning coach, and a personal trainer comes with its obstacles; however, it also comes with some great rewards. As an independent contractor at the Iron Asylum, I have a wide variety of clients: from general population weight loss clients to Olympic weightlifters with aspirations of competing, and everything in between. I always let the athlete’s goals and needs dictate the programming direction. After a thorough assessment of the athlete, I decide whether weightlifting is the best tool to use with them or not.

I always let the athlete’s goals & needs dictate the programming direction. After a thorough assessment of the athlete, I decide if weightlifting is the best tool to use with them, says @nicc__marie. Share on XIf an athlete wants to be more explosive and has the movement capability to perform the Olympic lifts, then I will 1000% incorporate some variations of the lifts and their respective accessories. That doesn’t mean I will build the entire program around Olympic weightlifting. On the other end, if a person seems apprehensive about the lifts and coaching the lifts wouldn’t be any more beneficial to their program goals than any other movement, then why force something on someone? In my experience, the more I work with a person and they see my training or some of the weightlifters I work with, their curiosity begins to grow.

About a year and a half ago, I had a runner come to me wanting to improve her mile times and training splits. She didn’t know much about Olympic weightlifting aside from what she saw through CrossFit but knew that she needed strength training in order to help improve her sport. As we progressed, she began to enjoy the feeling and intensity of lifting heavy weight more than her weekly 8+ milers and training split protocols. She grew curious in the gym and began asking about Olympic weightlifting and if I thought it would be something she could try. After working together for several months, I knew it was time to feed her curiosity, so I began incorporating clean pulls and power cleans into her programming.

Eventually, she found herself more excited to come to the gym to train than to lace up her sneakers and hit the road. One day she came to my wide-eyed and said, “I don’t want to run anymore. I want to weightlift, and maybe one day compete at a local meet.” From that day forward we made the transition, and now her training program is reflective of a true Olympic weightlifting program: incorporating the main lifts, weightlifting accessories such as pulls or snatch balances, strength lifts, mobility work, and general accessories.

Freelap USA: Weightlifting is a sport and can benefit from the strength and conditioning coaches who understand the needs of preparation. Can you share how you may do things differently than other weightlifting coaches?

Nicole Foley: In traditional sports, athletes have strength and conditioning and then sport-specific practice. For a weightlifter, our sport-specific practice is in the weight room. That doesn’t mean that the only thing we should be focused on are the Olympic lifts. Just like any other athlete, weightlifters need to have strength and conditioning and sport-specific practice.

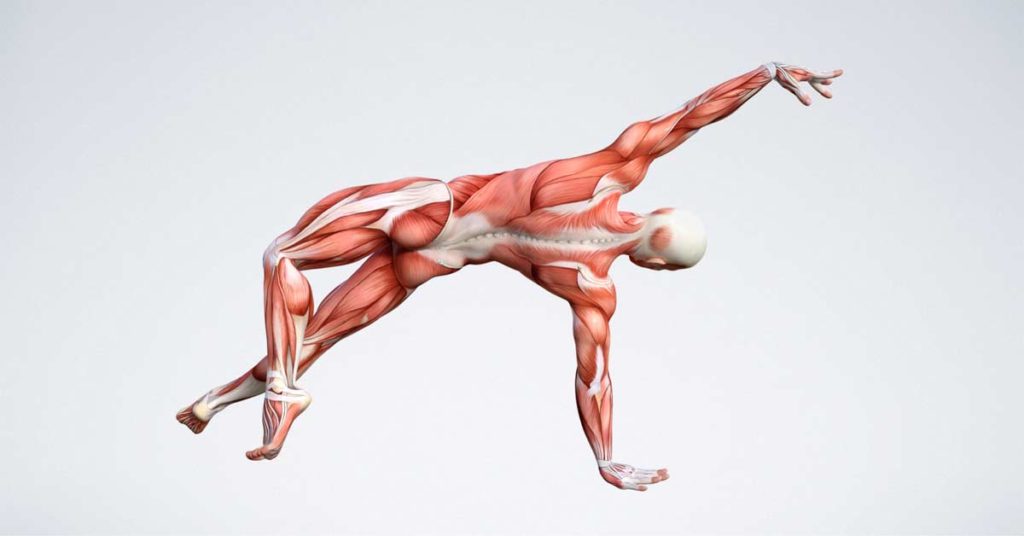

Now, this is obviously not going to be an S&C program in the traditional sense because we do not want to burn out the athlete to the point that their training suffers. However, it is imperative that weightlifters understand how to move and train to be well-rounded. Weightlifting exists predominantly in the sagittal plane; however, there is more going on than meets the eye. For instance, the rotational mechanics of the glenohumeral joint during a snatch or clean and the accompanying internal rotation torque at the hip during deep flexion are two examples of this.

Moreover, some of the more glaring (and common) non-sagittal movement deviations that we’ve all seen include lateral shifting in the bottom of the squat, torso rotation in the overhead position of the snatch, lateral shifts in jerk recovery, and excessive dynamic valgus knee collapse, to name a few. As coaches, it is our responsibility to correct these deficiencies, but on the platform that athlete is going to do whatever it takes to save a lift. So, it is also our job as coaches to make sure their bodies are prepared for anything.

On the platform the athlete will do whatever it takes to save a lift, so it is our job as coaches to make sure their bodies are prepared for anything, says @nicc__marie. Share on XAt East Coast Gold Weightlifting, I have the good fortune of training and working under my mentor, Phil Sabatini. Phil has an extensive background in the sport of weightlifting and is a former collegiate strength coach and exercise science professor. He taught me how to look at training and coaching weightlifting as more than just the snatch and clean and jerk. As I learned how to dissect the lifts, we spoke about the kinematics and biomechanics of the movements and the muscle actions of the body that can affect various points of the lift. This elucidated more discussion of general strength and conditioning and how we can use that to build a stronger and more sustainable weightlifter.

Every program I write prescribes an appropriate warm-up targeting mobility and/or stability (athlete dependent), along with accessory work to be completed after their main lifts. One thing I have noticed is that old-school coaches provide online programs that only include the Olympic lifts and main strength lifts; warm-up consists of an empty bar, load it and go. However, that could be a disservice to those athletes because not every weightlifter has an athletic background or foundation built to handle such repetitive movement. Even those with a solid strength foundation still need variety in their movement patterns to continue preventing injury and creating resilience.

Freelap USA: How have you changed your mind on exercise selection over the years in training the team sport athlete? Have you replaced any movement or dropped an exercise altogether?

Nicole Foley: My exercise selection hasn’t changed much over the years. It’s Olympic weightlifting: we snatch and clean and jerk, squat, pull, and press. What has evolved are the variations, technical drills, movement explanations, and cueing of the lifts.

These lifts are the most technical movements an athlete can perform. I have grown to recognize which variations I should incorporate more with certain athletes versus others. If I have an athlete who has a low back injury, then I am strategic about how often we pull from the floor and use more block work to provide the necessary training volume without compromising the athlete.

When it comes to coaching, your ability to provide context and general understanding is crucial. It can be difficult to explain to someone how to pull themselves under a bar, but one of the best analogies I’ve ever heard (and “stole”) was from my fellow coach, Brenden McDaniel. He described the timing of using the elbows to pull your hips down like pulling yourself down a waterslide. Never has anything so complex made so much sense.

Being able to improve on how you go about coaching and explaining the lifts is more valuable and practical than simply removing an exercise. There are progressions and regressions that you can utilize based on an athlete’s abilities. It is the instruction that is ever-changing in this sport because, as people change how they communicate with one another and learn from one another, a coach should adapt how they teach.

Freelap USA: Your dance background is a massive advantage for you, as you coached it for years. Can you explain the unique benefit dance has given you for teaching and observing the athlete?

Nicole Foley: Dance and weightlifting in the same sentence is not something you hear often, but the reality is that they are much more linked than you might realize. The goal of a dancer is to be strong, explosive, and able to accelerate and decelerate, move at different tempos, and change direction quickly, all while looking graceful and effortless in their performance. Weightlifting also checks all those boxes. There is a grace and fluidity to the Olympic lifts that only comes with true proficiency.

Dancers spend hours and hours of rehearsal time going through the same movements and movement phrases to perfect every last detail. It is a tireless but necessary process in order to perfect their craft. As a dance coach, you require the ability to look at the same eight-count phrase 20 or more times in search of any discrepancies between dancers to ensure the synchronicity of their body placement, technique, and timing. It is tedious for a coach to clean each movement to perfection, and there are times you will spend an entire rehearsal on one section of a piece and not even look at anything else until the dancers have it just right. The ability to go through this process and not get bored or aggravated with looking at the same thing over and over again is a skill in and of itself.

Weightlifting works in the same manner. You have to be able to look at a lift over and over and over again to see what is happening with the athlete in each individual rep. Then you need the knowledge and understanding of how to correct it. A lot of people look at a clean and see that they made the lift, or they missed the lift. But a coach understands that every make as much as every miss can have some sort of improvement. I spent my entire life looking at the same performances and dissecting them down to the one dancer’s arm being a degree or two out of a position in comparison to the others around them. In weightlifting, it isn’t about the synchronicity of the other lifters around them, but the synchronicity of the athlete and the barbell. Where is the athlete’s weight being distributed as they move through the lift, what is the timing of transitioning under the bar, are they pulling too early, etc.?

In order to perfect the minute details of these highly technical lifts, you have to break down and dissect what the body does as it moves through the positions, says @nicc__marie. Share on XIn order to perfect the minute details of these highly technical lifts, you have to break down and dissect what the body does as it moves through the positions. You need a sharp eye that can navigate through the technique in real time. It can be difficult to watch the same thing over and over again and not get bored, but whether it is my type A personality or my years of coaching dance, I find a calmness to breaking down the movement and enjoy the tedious process of fine-tuning the technique. Either way, I know I wouldn’t have the eye for this if it wasn’t for the endless hours spent cleaning choreography and training my eye to find the slightest changes or differences in movement, and I owe all of that to my first love, dance.

Freelap USA: Strength and conditioning is a very complicated process at times, but it’s often that coaches overthink it. How has your evolution as a coach improved your programming and design of workouts?

Nicole Foley: Confidence, plain and simple. In the beginning, I felt the need to prove how much I knew. I tried to incorporate as many exercises and movements as possible to keep clients from getting bored and to show how smart I was. Up to this point, my subject matter education was an ACE textbook, and I knew I had a lot of work to do.

After meeting my now-husband, Danny Foley, I began to see the opportunities in this field and the importance of understanding the basics. It doesn’t have to be complicated in order to be successful. We spent a lot of long nights studying, and he helped break down academic principles into real-world application. I stopped looking at programming as the Mount Everest of training and started looking at the body, how it moved, and how things felt when moving in a certain pattern. Being able to apply this gave my programming better structure by incorporating exactly what the athlete needed—no more and no less. With this newfound knowledge, my confidence grew, and my programming evolved naturally.

Whereas I used to switch up exercises too quickly in an effort to keep the athlete engaged, I began to understand that this was not an optimal way to develop proficiency and see true progression—especially in weightlifting. Depending on the training age of the athlete and the goal of the program, we spend 3–4 weeks on the same movement variations and provide variety in the accessory movements. It is a lot more difficult to understand and improve a technical deficiency in the lift if you only see that variation once every two months. When I reinforce a movement position or variation for several weeks, the athlete can see their progression and direct their training focus to what their specific lift variation tries to emphasize. Then I use the accessory lifts to progress and challenge the athlete while breaking up some of the monotony of training.

My programming is still evolving as I learn and progress forward in the field, but at the end of the day, consistency is key. Without that consistency, true technical knowledge of the lifts will never develop.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF