If you were involved in sport in 2010, you almost certainly encountered discussions about vitamin D. It was very much the supplement du jour back then. Plenty of research showed its function in performance, as well as the prevalence of insufficiency. This research kindled interest that remains strong today.

What is it?

Vitamin D refers to a group of vitamins. The most important are D2 (ergocalciferol) and D3 (cholecalciferol). The sun is the primary source of vitamin D for most people, as it isn’t widely available in foods. This situation obviously causes issues in individuals who don’t get much sun exposure. More on this later.

What does it do?

Vitamin D plays many important roles in the body. There is some evidence that it affects the risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Low levels of vitamin D can have a negative effect on the immune system, muscle function, stress fractures, and injury risk.

These studies suggest that we need to ensure athletes have sufficient levels of vitamin D. The main issue here is availability. Since the main source of vitamin D for most people is the sun, insufficient sunlight exposure causes problems. This can be either a result of low levels of ambient sunlight (especially in winter), or spending most of the day indoors. Some conflicting evidence suggests that sunscreen use may also reduce vitamin D levels.

In a 2012 paper, leading sports nutritionist Dr. Graeme Close measured vitamin D levels in the blood of a group of athletes which included soccer and rugby league players, as well as non-athletes. Close took blood samples during the winter months, with a blood vitamin D level of 100nmol/l suggested as optimum. The results were staggering. Only one of the 61 athletes had a vitamin D concentration of 100nmol/l or greater. The median value among the athletes was less than 75nmol/l, and less than 50nmol/l for non-athletes. You might think this is a problem exclusive to more northerly latitudes, but a study of NCAA athletes reported similar results (It should be noted that the authors use different units to measure vitamin D). In a study of Middle Eastern athletes, 91% were deficient, with 59% showing an increase in stress fracture risk. So even though we might know we need sufficient vitamin D—especially from a performance standpoint—many athletes still aren’t getting enough.

How much vitamin D do we need on a regular basis?

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for vitamin D varies from country to country, and it is typically 400IU-800IU per day. This amount probably is enough to avoid deficiency but not to ensure optimal levels, especially for athletes. The problem is that there are no accepted guidelines for optimal vitamin D intake for sports performance, although research indicates an optimal blood value of around 100nmol/l. To achieve this value, Dr. Reinhold Vieth (1999) recommends a daily intake of 4000IU. This amount sounds reasonable, although I used to supplement with 5000IU per day. After three years at this level, my vitamin D levels were still less than 100nmol/l. Nevertheless, 4000-5000IU appears to be a decent daily target.

You can get too much of a good thing, however. You need to be wary of vitamin D toxicity, (hypervitaminosis D). Symptoms include fatigue and muscle weakness—hardly ideal for athletes—vomiting, decreased appetite, and dehydration. In some cases, it can also lead to calcification of soft tissues. Fortunately, the Vieth paper (it is good–please read it!) asserts that there isn’t any evidence of adverse reactions at blood vitamin D levels of less than 140nmol/l, which would require approximately 10,000IU of vitamin D per day.

One thing to consider is that vitamin D is fat-soluble, which means it can be stored— potentially making toxicity more likely. Toxicity can only occur through food/supplemental sources, however, as the creation of vitamin D through sunlight has a feedback loop that guards against excess. The half-life of vitamin D within the body in its storage form is about one month, so people getting a lot of sun exposure and supplementing should be careful throughout the summer and autumn months.

Vitamin D Sources

One thing to be aware of is the different forms of vitamin D. Vitamin D from sunlight is of the D3 variety. Vitamin D from vegetables and fortified products often comes as D2. Which is better? Most research indicates that D3 is much more effective than D2 in humans, although some studies counter this.

Where can we get vitamin D? Some foods contain it, although not in especially high amounts. Oily fish has around 750IU per 100g, and this is D3. Foods like mushrooms contain D2, although the amount can vary. Fortified milk and juice products can contain both varieties.

Sunlight, of course, is another option. Total body sun exposure can easily provide 10,000IU (Vieth), which is plenty. However, the obvious risk here is skin damage from sun exposure, including the risk of melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma. This paper from Barbara Gilchrest in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition examines both sides of the issue. Another factor to consider is that dark skin requires a greater amount of sun exposure for adequate vitamin D formation, which is why African Americans are at greater risk of vitamin D insufficiency.

Supplementation

The final avenue is vitamin D supplementation. The most common regimes are between 2500IU and 5000IU per day, although 50,000IU per month (1660IU per day) over the winter months was effective in increasing vitamin D levels in a group of elite athletes. I used to take 5000IU per day in the winter, when my sun exposure was essentially non-existent, and 2500IU in the summer when I was getting more sun. Ideally, you should choose a supplement that contains vitamin D3, the more readily available form. Often this comes in an oil-based capsule, which is fine; if it comes in more of a powder, consuming it with fatty foods will increase absorption. Supplementation has some benefits. You know how much you’re getting (assuming the manufacturers are truthful), and you aren’t risking skin damage from the sun.

Does supplementation help? The Close article cited earlier has a second part. The researchers recruited 14 footballers from a Premier League club academy (not a huge sample, admittedly). Half took 5000IU of vitamin D per day for eight weeks, the other half a placebo. The players did a battery of physical tests before and after supplementation.

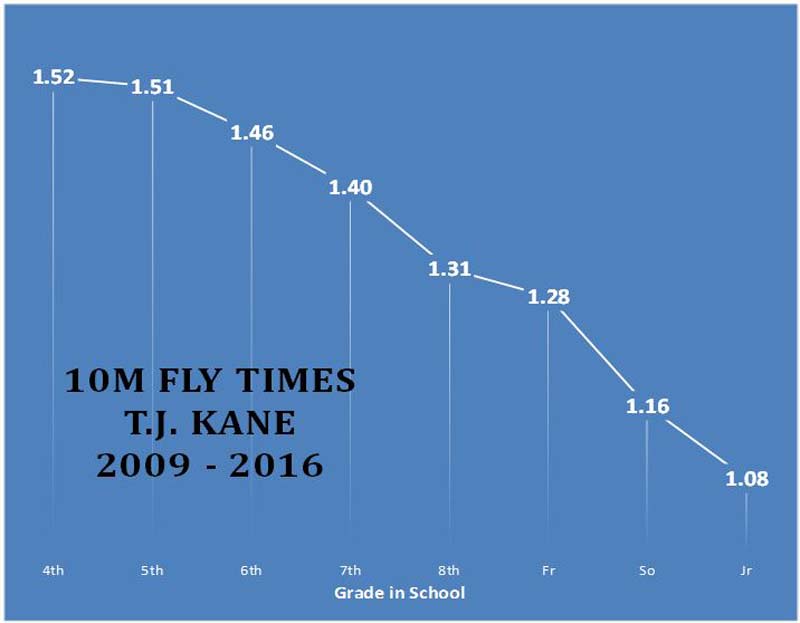

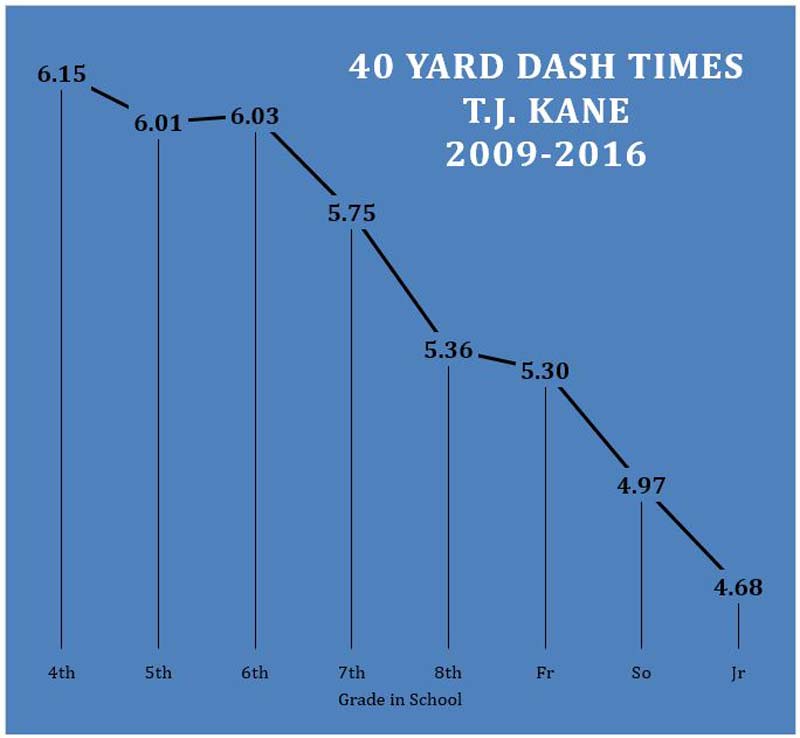

Both groups increased their plasma vitamin D levels, although only the supplementation group did significantly better—presumably the placebo group was also getting some sun exposure. The supplement group saw a significant improvement in their vertical jump and 10m sprint performance, while the placebo group didn’t. There was a trend toward significance in improvements in 1-RM bench press and back squat too; this means it didn’t quite meet the significance level but was close. The supplement group improved bench press on average by 6.5kg, compared to 2.5kg in the placebo group. Back squat 1RM improved by 9kg, compared to 3kg in the placebo group.

Makes you want to use vitamin D supplements, doesn’t it! Just remember that these athletes were not only most likely deficient to start with, but also still developing physically. It follows that greater improvements would be likely. The same research group conducted a larger research trial a year later and found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on performance measures.

In a group of ballet dancers, daily supplementation with 2000IU increased vertical jump (a measure of power) and reduced injury risk. In a group of Greek professional soccer players, increased vitamin D levels were associated with performance improvements in various jumping exercises, sprint performance, and VO2 max. Subjects in this study did not undertake supplementation but instead received all their vitamin D from the sun.

Some early research shows that vitamin D may have a role in increasing type II muscle fibers. This research was conducted in stroke patients, so we have no idea if it would still be the case in healthy individuals. Similarly, animal studies suggest that vitamin D intake might have a role in protein synthesis. These results have not been replicated, especially in humans.

Vitamin D supplementation may have a protective effect against injuries, particularly stress fractures. In a group of female Navy recruits, daily supplementation of just 800IU vitamin D reduced stress fracture risk by 20%. Similarly, higher intakes of vitamin D in a group of female cross country runners were associated with a decreased risk of stress fracture.

Vitamin D supplementation can increase testosterone levels. Higher levels of testosterone may be associated with more favorable adaptations to resistance exercise (although the evidence on this isn’t always great), and may also increase competitive drive. In this study, daily supplemention of 3332IU for a year led to a significant increase in testosterone levels.

Vitamin D supplements can have a positive effect on muscle recovery. In a 2013 study, researchers gave a group of males either 4000IU per day for 28 days or a placebo before they underwent a fairly strenuous exercise protocol. Subjects who supplemented with vitamin D had a lesser increase in biomarkers associated with muscle damage and soreness than those in the placebo group.

Finally, sufficient levels of vitamin D can have an important knock-on effect by improving post-exercise recovery, possibly by causing an increasing in anti-inflammatory cytokines. Low levels of vitamin D are also associated with an increased risk of illness.

Testing of Vitamin D

Vitamin D testing is relatively easy and straightforward, depending on where you live and regulations governing that region. In the UK, vitamin D testing can be conducted via a GP (if you ask nicely), or you can order a kit online for less than £40. In the USA, tests cost about $50. In Australia, vitamin D tests cannot be sold directly to consumers, Testing needs to be conducted by a practitioner.

After getting your vitamin D tested, it’s important to know how to interpret the results. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) provides these guidelines:

- <30 nmol/l – deficient

- 30-50 nmol/l – inadequate

- 50> nmol/l – adequate

When I was an athlete, my governing body regularly conducted vitamin D testing. Their guidelines were similar to the IOM–they didn’t want any athletes below 50 nmol/l, and preferred us to be around 100 nmol/l. Some blood tests give results in ng/ml, so you will have to convert to nmol/l. Plenty of online calculators do this.

Summary and Conclusions

Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency are common in athletes. This can lead to a whole host of issues, including increased injury risk, poorer recovery, reduced muscle strength, and decreased immune function. Vitamin D can be obtained in relatively small amounts from food. Sun exposure represents an excellent source of vitamin D. However, the possibility of skin cancer should not be taken lightly.

Supplementation appears to be the safest way to increase vitamin D levels. However, there are no accepted guidelines on supplementation levels for athletes. The majority of research uses daily doses of 2500IU-5000IU per day. This amount represents a good starting point. It is generally accepted that intakes below 10000IU per day are safe for most people. Regular blood testing of vitamin D levels is relatively inexpensive and gives a good indication of current supplemental needs. While the evidence shows that athletic performance can suffer if vitamin D levels fall below 50nmol/l, it is not clear that levels well above this enhance performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF