Years ago, I took on the role of sprint coach at Triton Regional High in the small town of Byfield, Massachusetts. I had volunteered sparingly the year before and enjoyed it enough to give it a real try. Four years removed from competing collegiately in the 400m, I came in armed and ready to go. Unbeknownst to me, my grasp on training and athletic development concepts was tenuous at best—true “unconscious incompetence.”

It’s funny how inheriting a fairly talent-laden squad can disguise the truth: My athletes were succeeding in spite of me. However, I’d like to think that my heart was in the right place and I tried my best to maintain good relationships with the athletes during these “new days.” At the end of the day, some school records were set and some individual championships were won, but I can now say that I was standing still as a coach.

I read sparingly on issues related to training and my use of speed work was something to be desired. I was giving workouts, but not developing athletes. These are two very different things. Soon, the athletes with some talent who I had inherited were seniors and the thought crept in that, while I was doing okay, these kids deserved even better. Looking back on it now, I often have a severe case of the “what-might-have-beens.” They say that you coach what you know, and what I knew was not always applicable to 14- to 18-year-olds.

I was giving workouts, but not developing athletes. These are two very different things, says @grahamsprints. Share on XThere was soon a dearth of raw talent, and for whatever reason, a mass exodus of male multi-sport athletes. The “cats” had, in effect, gone away. Every once in a while, I heard a voice in my head asking, “Did you have something to do with that?” If I am honest with myself, I don’t know. Maybe. That “maybe” is all I need.

I know that training could have been more fun and I could have gotten out of the way more. So I did what I had done throughout my entire childhood—I read. I tried to understand energy systems at play in the sprinting events. I purchased programs from coaches who had forgotten more than I knew. I stumbled across blogs and read the musings of other coaches who seemed far more honest with themselves than I had ever been. I got back into doing sprint drills and plyometrics myself.

Since then, I have been slowly adding pieces to our sprints program in a way that makes sense without overwhelming myself or the athletes. Four years into my own paradigm shift, I think I have read enough to move the stage-of-learning needle to “conscious incompetence.” I know that I know nothing and years from now I’ll hopefully know something. Author Pam Allyn says: “Reading is like breathing. Writing is like breathing out.” After lots of reading, it is time to breathe out. Here are three changes that I am currently working through.

The Warm-Up

I post a lot of our warm-up drills on our Triton Sprints Twitter page. I want the kids to be proud of their athletic development. I am hard on them, but the reality is that they move better than I did at their age. One of my college coaches once referred to me as a “biomechanical nightmare,” and he wasn’t wrong.

My thinking used to be that the warm-up was just that: A chance to increase body temperature before we got to the real meat and potatoes—the workout. But the thing with “biomechanical nightmares” is that they can still be fast. Their limbs may fly all over the place, their arms may cross the midline, and they may exhibit knock-knees with every jump, but they are still fast. Accepting this fact presents as lazy.

Speed in the presence of this dysfunction is something that makes me nervous because I don’t think it is sustainable over time and it leaves seconds on the track. I never want to assume that puberty and maturation will fix the issues. Our warm-ups typically start with 90/90 or alligator breathing—roughly two minutes for athletes to pause and hit reset on their day. I don’t always know everything that went on in their day, but I do hope that track practice is a chance for them to deal with it in at least one way.

We usually go into dynamic stretches/drills after that and then sprint drills. I am blessed yearly with terrific captains and this year is no different. They take charge and, for the most part, move extremely well. We have five different warm-ups employed for different types of workouts. It seems excessive, but I work under the assumption that they forget everything once the next week comes along.

I treat warm-ups like an audition. Who is focused? Tired? Who does something they couldn’t before? says @grahamsprints Share on XAcceleration days feature sprint drills that focus on pushing; max velocity days have a cycling- and posture-centered theme with small ground contact times. Lactate days focus on more of a technical buildup. On circuit days, I try to back off and let the captains decide. I treat the warm-ups like an audition. Who seems focused? Who looks tired and like they have regressed? Who can do something that they previously couldn’t? I think we try to keep the intent on everything high. Some days our warm-ups are longer than the speed workout itself. At this age, skill acquisition matters more than working out.

We have two lines, one behind another. I have a captain demonstrate everything and the group gives them a round of applause because athletic development is a cause for celebration. I typically follow up with an incorrect demonstration. Another captain is then called out and demonstrates it again. It can be high pressure, but they always rise to the occasion—this transcends the sport, and matters in real life.

Line one goes. I offer my critique of line one to line two, which is usually comprised of underclassmen. Sometimes they get it and sometimes they don’t, and I can live with that because it’s part of the process. There isn’t time to do this on every drill, but deciding which ones are important to you as a coach and then coaching the heck out of them is a good place to start.

Decide which drills are important to you as a coach, and then coach the heck out of them, says @grahamsprints. Share on XThe group warm-ups serve as a chance for everyone to work together on drills to promote the movements that pertain to the context of the day’s theme. The general strength created through these warm-ups is underrated, especially for the athletes who have never done a sport before. If they couldn’t A-march in December and they can in February, they got stronger. As Dr. Ken Clark says, “If you can’t hold this position isometrically, you can’t do it dynamically.”

The warm-up is also a chance for me to hit reset after completing my day at the elementary school just 15 minutes away. I get to practice the cues and language, and shine up the figurative language that will no doubt be abundant in the workout of the day. The use of specific language and cues makes the athletes more coachable over time. Give them options. I usually end with a challenging drill predicated on a bit of “violence” to see who is connecting the dots between everything.

After nine years, I can say that I am finally developing athletes. I take pride when a freshman improves from 8.0 to 7.5 in the 55m in two months, and looks exponentially better doing it. With consistent training, there will be a place for him one day on our team to compete in some event.

Timing Speed Training

People say speed is the hardest biomotor quality to train and they aren’t lying. I used to believe that speed was largely either something you had or something you didn’t. A few years ago, I stumbled across Tony Holler and the “Feed the Cats” mentality. I was intrigued instantly, but didn’t dive in entirely. I didn’t have a timing system, so I was running flys and accelerations for years without feedback. They were flys alright, but they lacked purpose and competitiveness.

#Feedback ensures that improvements are quantifiable long before meet day approaches, says @grahamsprints. Share on XPeople talk down about today’s kids, but most of them like being timed and they like knowing they are getting better even more. Improvements are now quantifiable long before meet day approaches. Having to perform in practice almost daily is (slowly) making meets somewhat commonplace. We often use hallways (still no shin splint bug) and have only sneakers on, but the intent is there until we are graced by sunny weather. They are used to competing long before the starter’s gun fires.

I wish I had done more of this when I started. I think most of the athletes I coach now know roughly what 10m time they need to enter or move up from their current “mph club.” T-shirts have been ordered (thanks to The Medina Bees Track and Field Twitter page for the great idea). I hope they continue to strive and feel a sense of pride as they earn their shirts. I don’t care what anyone says: Being fast is cool, and the rest of the student body needs to know about their hard work. Moreover, speed is the greatest indicator of success in any track and field event, and in all sports.

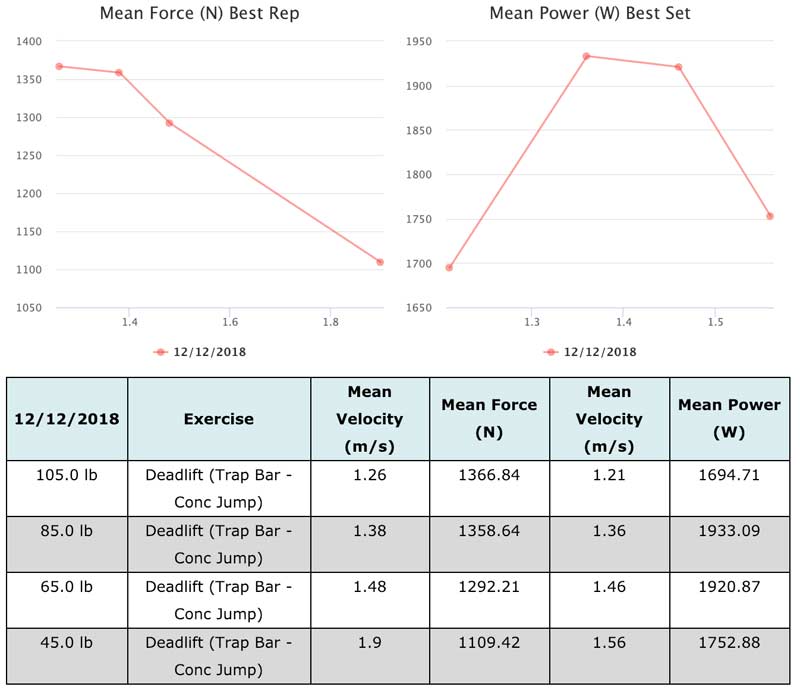

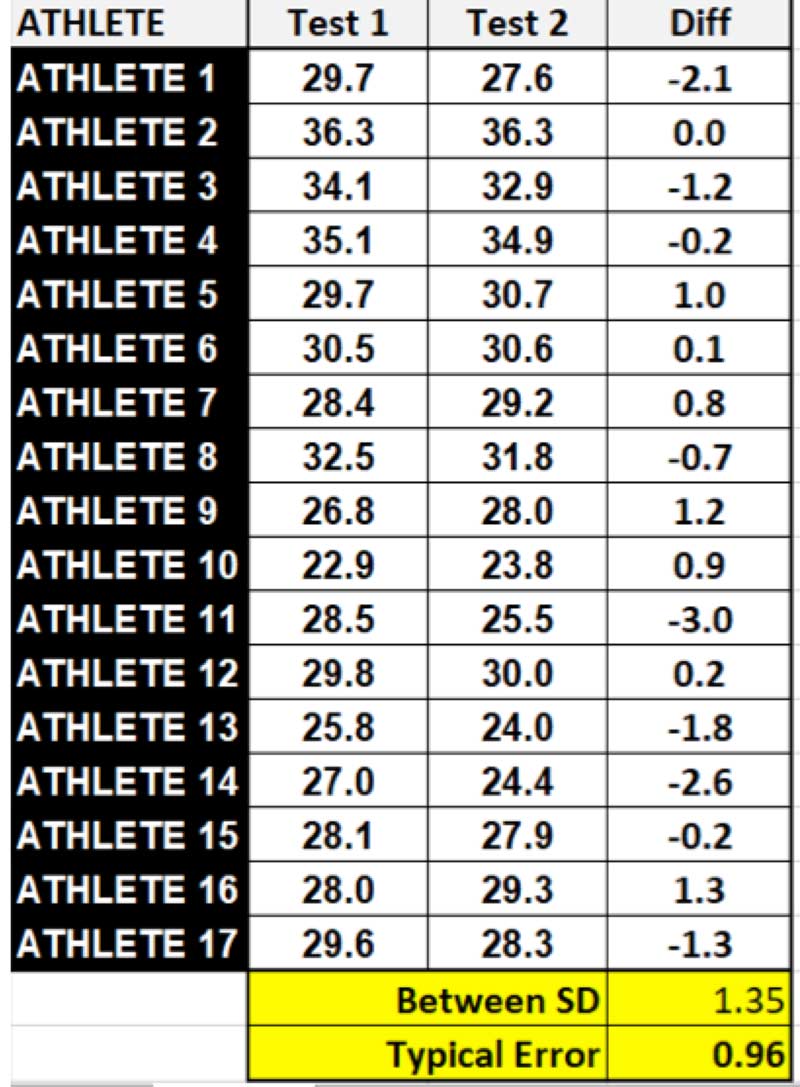

I have become intrigued with the math behind the speed. Take a look at the data below.

Avg. Speed

22 second 200m= 20.33 mph

23 second 200m= 19.45 mph

26 second 200m= 17.21 mph

27 second 200m= 16.57 mph

50 second 400m= 17.9 mph

55 second 400m= 16.3 mph

60 second 400m= 14.9 mph

These are the average speeds needed to hit certain times in the 200m and 400m dashes. Just take the race length in meters and divide by the time. Then multiply that number (meters per second) by 2.237 (1 m/s = 2.237). I am recording each athlete’s personal bests in their events this year and comparing them to see if there is a range of how many mph you need to be above your event goal time to actually hit that time.

For example, our best 55m female this year has run 7.54 seconds (16.32 mph average) but has hit 19.28. This is a difference of almost 3 mph from her 55m race average. Our best 300m male has run 36.45 (18.41 mph) in the 300m dash. He has a peak mph of 21.10 mph in practice (granted, sneakers in a hallway isn’t the best testing condition). That leaves a speed reserve of about 2.5 mph.

Regardless, the speed has raised their respective ceilings. Exploring this further could help identify obvious deficiencies in certain training blocks. If there is a female who can run 19 mph but struggles to break 60 seconds (14.9 mph) in a 400m outdoors, that is something to be reflected upon. Why can’t she do it? Fear? (Not everyone can take themselves to the dark place.) Poor race model? Subpar performance on lactate workouts (again, fear)? Is it possible a minimal amount of aerobic work can help her? Or maybe the 400m was never a goal for her, and deviating from the current training takes her away from becoming great in other events.

If you’re last to the ball, how strong you are or what sport-specific skill you have doesn’t matter, says @grahamsprints. Share on XI know I will never regret prioritizing speed, especially in the early stages of their career. I hope, in the fall, that the field sport coaches notice their athletes are moving just a bit better and more swiftly. If you are last to the ball, it doesn’t matter how strong you are and what sport-specific skills you have. When it comes to high school athletes and speed training, intent takes the cake over the volume that they do. They have to get there before they can go anywhere.

Changing the Weight Room

In college, I lifted like a “bro.” So, for the first several years of my coaching career, I let athletes chase numbers, as football players often like to do. I failed to get them to check their egos and most prescribed exercises were in the hypertrophy rep range. Everyone lifted and it was chaos. I am sure some of them doubled up at their morning lifts.

Things are greatly simplified these days. We do not have many kids capable of lifting huge amounts of weight and that’s fine. Strength is a skill that needs to be developed. If the technique is there, with consistency they will get stronger. At their age, lifting helps posture and speed. After a certain point, I am not sure it continues to do so.

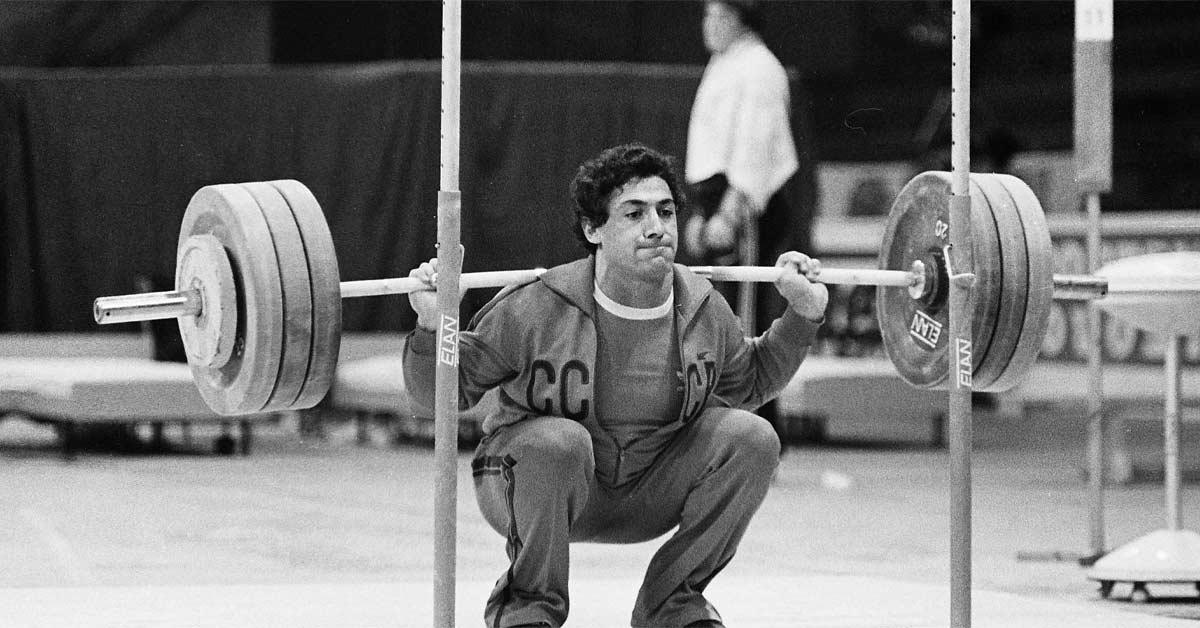

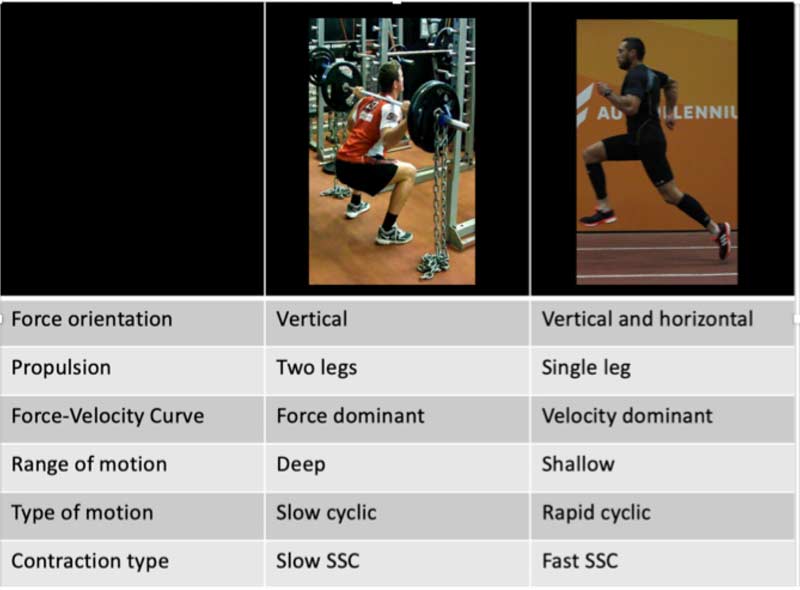

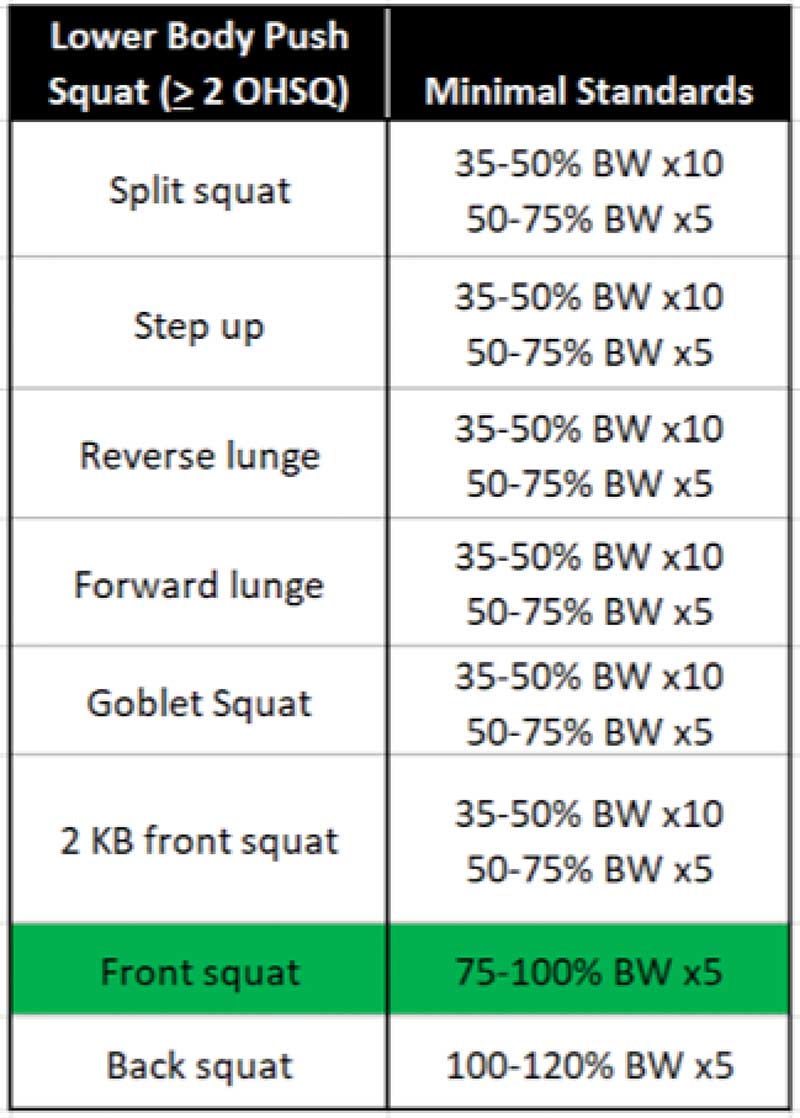

Most freshman don’t lift. First, because we don’t want to add any more to their plate. Second, they are getting stronger through bodyweight and general strength circuits. The weight room coach is actually our throws coach, Katelin Invernizzi. I may be a little biased because she is my fiancée, but she gets them moving better quickly. I read somewhere that sprinters don’t need to have too much mobility. I get that, I really do. We don’t need pliable ballerinas, but in my experience if a kid has a poor front squat technique, his block start is a mess as well. Strength lifting is done on acceleration days. Squat mobility is a focus. Again, the focus is the movement patterns, not the weight.

If athletes check their ego and look like they are engaged, I will post them on Twitter. Prep is usually done with Katelin in the middle, cueing them through each drill and fixing technical errors. They are done in 15-20 minutes. On lactate days, they do a giant hypertrophy set, in and out with good technique. Hypertrophy is great for tendons and joints. It’s a slower, less technical day, so the kids can look stronger and listen to music.

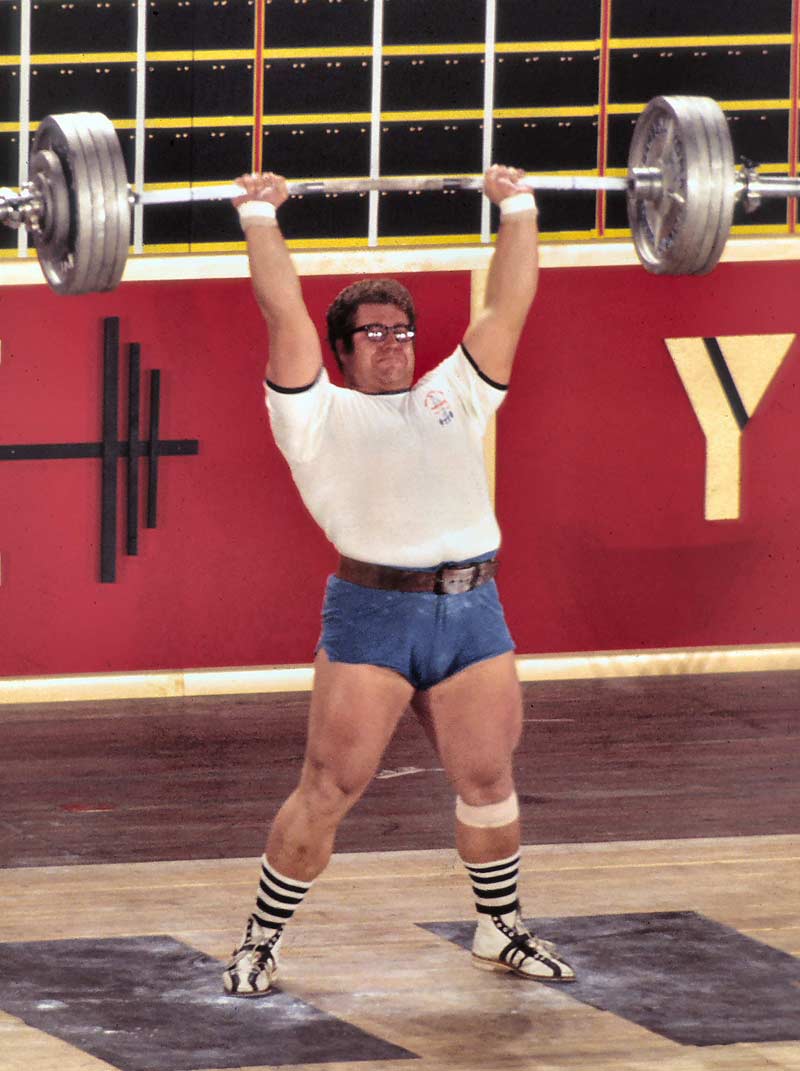

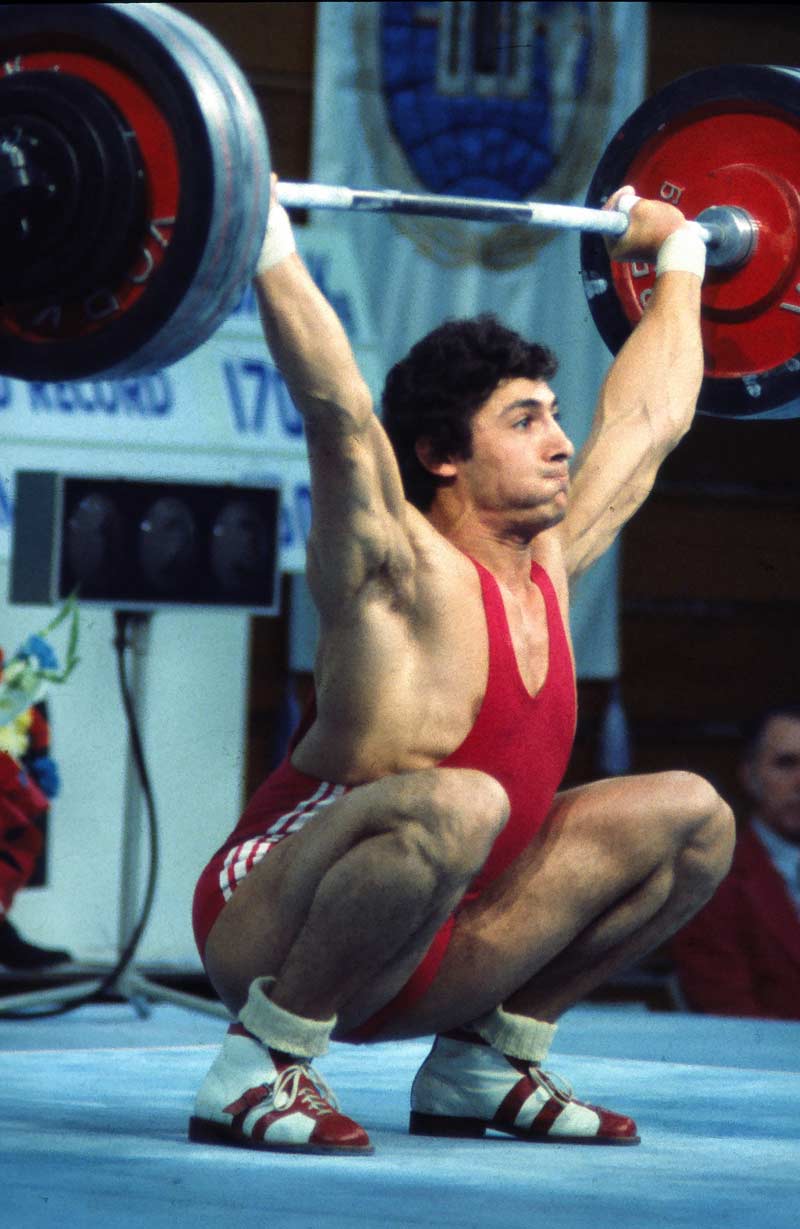

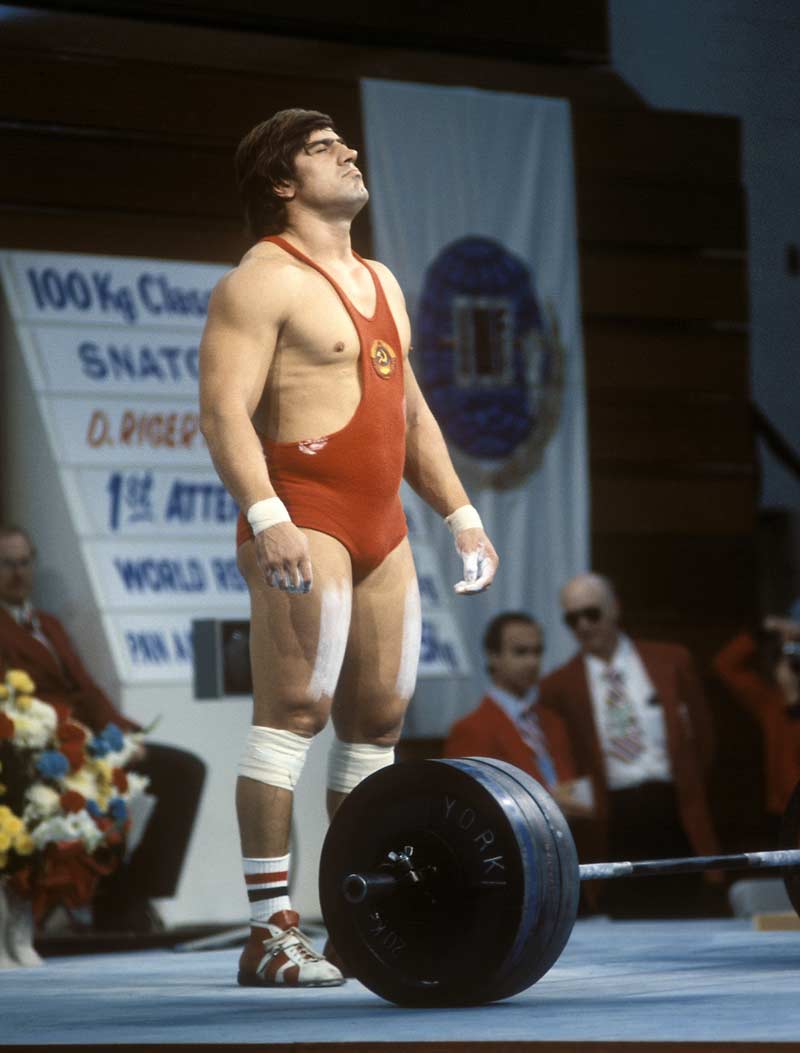

The third day of lifting is an introduction to Olympic lifting on max velocity day. It is broken down well and again in a circle, while they are cued through each drill. The last thing we want is to end up on the wrong side of Twitter because a video of one of our athletes doing a back-breaking clean went viral. It is our job to protect them and to develop them.

Let me be clear: Olympic lifting doesn’t supplant sprinting. Our message to our athletes is that the weight room is a support but not the answer. At the end of the day, being able to accelerate and decelerate under a bar is an athletic movement. Improvements here are often best expressed as the athlete being more receptive to cues outside the weight room, and being coachable is a good thing. Plus, it is fun and sometimes fun is a goal. We want our kids to leave Triton knowing how to work out, because working out feels good. Some of them will never run a step again, but options are a wonderful thing to have.

Moving On

Making mistakes is a natural part of the coaching experience. At some point, the things you have always done no longer work. The “adapt or die” mentality is very real. Facing that fact head on is often not an easy task. It’s 2019, and there is a plethora of information available. I can’t imagine not taking advantage of that.

I am a product of every coach I have ever met, says @grahamsprints. Share on XI am thankful for the programs I have purchased over the years that allowed me to enhance my coaching knowledge. Spending money is a necessary thing to become better at your craft. Connecting with all of the amazing coaches on social media has allowed me to continue to strive to be better for my athletes. I have learned from sprint coaches, distance coaches, sports coaches, CrossFit coaches, bodybuilders, and powerlifters. I am a product of every coach I have ever met.

“Stealing” ideas and making them your own in a way that makes sense to you is what learning is all about. With this variety, I think our program has gotten better even if we don’t set records every week. With consistency, more records will fall soon—I am sure of it—and that cats will come home. After a track practice, I am exhausted and take comfort in knowing that I am slowly rectifying some of my earlier gaffes. Movement quality is king and speed always kills.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Nate Brookreson was named Director of Strength & Conditioning for Olympic Sports at NC State in June 2015. His primary training duties are with women’s basketball, swimming, and diving, and men and women’s golf, while supervising the implementation of training for over 500 student-athletes.

Nate Brookreson was named Director of Strength & Conditioning for Olympic Sports at NC State in June 2015. His primary training duties are with women’s basketball, swimming, and diving, and men and women’s golf, while supervising the implementation of training for over 500 student-athletes.