[mashshare]

Everyone is looking for the best workouts and methods to improve vertical jump performance, and at Exceed Sports Performance and Fitness, we’ve found that the kBox is a great tool to help with eccentric strength for serious hops. With the use of our own testing and training protocols, we implemented some additional methods that helped improve our athletes’ jump performances, and in doing so found some benefits to horizontal power as well.

Shane Davenport and I previously talked about different training methods and the best exercises for the kBox and kPulley, and now this article will focus on the flywheel’s role in vertical jump training and vertical jump exercises. It’s hard to narrow your focus and aim towards improving one specific quality without interfering with other qualities along the way. However, if your goal is to get your athletes more explosive and jumping higher, this piece is for you.

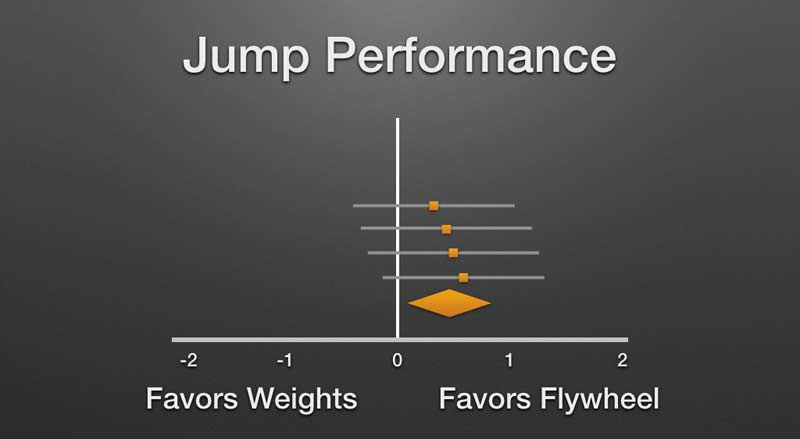

The verdict on #flywheels is in: A kBox or other isoinertial equipment can help athletes jump higher, says @SPSmith11. Share on XThe verdict for using flywheels is in: A kBox or other isoinertial equipment can help your athletes jump higher. This article is not about convincing you to use flywheels for jumping—the science will do that—but to assist you in maximizing the benefits of flywheels through smart programming. It will help you make better athletes, as well as better jumpers.

The Science of Jump Performance and Isoinertial Training

An earlier review on flywheel science briefly covered jump performance, and old research on the Vertimax. This section will not be detective work, but more like an extended list of what the scientific studies have shown works. My facility uses both the kBox and kPulley, but only as a fraction of our programming. Our athletes lift, jump, sprint, and do whatever else we think will give them their best chances on the field, so don’t think this article will only cover flywheel use.

We’ve had a great deal of success with our jumping protocols, and have seen athletes at the highest level improve their jumps and outperform the vast majority of their peers. In unison with our standard training programming, we use flywheel training to help our athletes absorb force, stop and cut aggressively, and be more efficient in their sport movements.

We had to figure out what happens when you add flywheel training to a program, not replace what you do. We use both the kMeter and force analysis when determining who needs extra “tutoring” and who may just need a taste of flywheel-specific jump work. At this point, it seems any incorporation of flywheel training into an athlete’s program will yield a positive outcome. Of course, the how, where, and why play a large role in how effective that outcome is, but if the trend is positive, keep doing what works.

Although there isn’t a lot of research on flywheel training specifically for jump performance that I know of, several studies have hypothesized that faster inertia may make a difference. Our conclusions are the following:

- Movement specificity matters, so if you want to be better on one leg or two legs, training on a flywheel should mirror that need.

- General power development matters as well. Train for overall strength and power and don’t get lost in specificity only.

- Keep in mind that movement variability is still important to avoid mismanaging stresses and risking those potential wear-and-tear overuse injuries.

The most interesting study in all of the research on jump performance is the handball paper published a few years ago. We like it because the machine was less specific to jumping, as well as the Polish study, which experimented with different loads of inertia and jump performance. Both enhanced vertical jump performance; specifically, the countermovement jump where a lot of us make our money. There was also some unique research on patients who were forced to be in bed for extended periods of time and their rate of jump improvement compared to the control group. Anyone dealing with post-surgical clients who need to “catch up” might be interested in the results.

Profiling Good Candidates for Flywheel Sessions

A bad jumper with a poor training background will get better doing nearly anything, but well-trained athletes who are good at a few things are the main population coaches care about. How do we make the good great, and how do we make the great the best? Getting athletes better is easy when they are new to training, but how do you give your athletes an advantage if everyone else is training hard and smart? Information dissemination is arguably easier and more widespread than ever, so it’s becoming more important to keep experimenting, testing, evaluating, and adjusting.

From testing jumps with force plates we found that athletes with poor jump performances tend to have problems storing and releasing energy. If an athlete is unable to handle the eccentric forces of the descent (pre-jump), they will have a difficult time braking, reversing direction, and applying force with any appreciable effort. Traditional methods of improving these abilities still make up the majority of our training, but incorporating a tool that is almost perfectly designed to improve these qualities simply makes sense to us.

Video 1. Testing athletes using force plates with dumbbell jump exercises has a lot of value. A main goal with our jump testing is to profile who may be a great responder to loaded jumps with flywheels.

If you want to profile clients, you must spend a little time and invest in proper equipment. Eye tests are a thing of the past and some simple equipment can get the job done, but some of the tech out there now is a game changer. The addition of quality force plates this past year has made a huge difference in our ability to profile a client. We can compare static (squat jump) and dynamic (countermovement jump) jumping to categorize athletes using the Eccentric Utilization Ratio. Using advanced or simply more metrics does add a little bit of work for coaches at first, but in the long run, analysis improves results because the way an athlete jumps dictates how a training program will help, or not.

In terms of simplistic categorization, we generally see athletes who need basic training, advanced training, or highly specific training. Understanding when and what methods to use on which population isn’t all that straightforward; however, here are some simple guidelines on the approach.

- Beginner Trainees: General exposure to standard training and potentially adding flywheel training using common movements is recommended for this level.

- Advanced Trainees: At this level, you can incorporate more advanced flywheel training that focuses on intensive loading and maximal power development.

- Specific Training: Although best reserved for high-level athletes, specific flywheel training, using both low and high inertia, will help athletes achieve specific results. This could be jumping higher or returning to competition.

Beginner athletes who need to develop a sound foundation can jump into flywheel training after a few months of learning movement patterns in the weight room. After an athlete advances from new to experienced, we can help them hone in on specific outcomes based on a better indication of their ability and their response to training. Advanced athletes, those with 2-3 years of real training, tend to respond to demanding and intense training without much need for fancy workouts. They are similar to beginners in their need to polish the fundamentals, but they can no longer get better by just showing up. Specific training can be used at any level, such as rehabilitation programs or elite sprinters, but customized training helps advanced athletes who are now entering the realm of hard gains.

How to Make a Difference

The simple answer to what is the best exercise for jumping is easy: anything that resembles jumping. You’ll have slow, deep countermovements and short, fast, stiff jumpers, and it’s important to focus on what people do well and either bring up the lagging movements or fine-tune their strengths. How you train will dictate how you jump. Attention to detail and specificity are often the name of the game in this world, and it’s no different when it comes to the flywheel.

- Train Speed-Specific Patterns for the Desired Outcome: Fast or slow, heavy or light.

- Use Appropriate Depths: This may require more than just one depth.

- Use Appropriate Vectors: Are vertical patterns enough?

- Expect and Monitor for High Efforts and Quality Output: You can’t expect exceptional results from mediocre efforts.

Some single leg training has helped vertical jumping with poorly developed athletes who just need something, but jumping with two legs with a flywheel works better than split squatting at higher levels. Especially when we want fast movements, the squat pattern is just more appropriate and more effective than split stance patterns.

Lateral squatting has some research behind it in regard to jumping, but we tend to use that a lot less than bilateral patterns. Why? The research shows that unilateral movements help, but more so for change of direction. So, if you’re seeking raw horsepower, bilateral movements are better. Flywheel squatting improves jumping, sprinting, change of direction, and even muscle thickness in only six weeks with athletes.

Like variable resistance training, #flywheel training can be used at a multitude of depths, says @SPSmith11. Share on XAnother point of contention with coaches and athletes is the depth that squatting is effective to. As I mentioned above, we use force plates to determine what qualities we need to focus on, but we can also experiment with countermovement depth to better determine how an athlete should approach the test. If an athlete performs better at shallow depths than they do at deep squat jumps, that may dictate a slight change to the programming, but it often just gives us a quantifiable reason to work on jumping at the appropriate countermovement depth. Like variable resistance training, flywheel training can be used at a multitude of depths. While most people prefer to squat shallower and lighter, we also use deep ranges of motion for people who have difficulty achieving similar depths with bar-loaded variations.

Video 2. Deep and heavy flywheel squatting is simple, but yields great results. Focusing on the basics will work immediately and help prepare for advanced exercises later.

Because we are often asked about horizontal exercises in regard to vector training, we find that barbell and band training (supine movements mainly) work best. There has been research from Sophia Nimphus and her colleagues that exposed the limitations of horizontal training in jump performance, and suggested that the barbell was superior to the cable. It’s worth mentioning that most clients who are interested in jump height are also interested in acceleration and speed.

In the study, barbell work improved sprint performance for a much greater distance than forward-stepping cable work, and we’ve found it trickier to train the horizontal vector with the flywheel anyway. Movements that require a long learning process should be worth the time spent, so based on experience and the research findings, we don’t waste a lot of time on it. We spend a considerable amount of time directly on sprint performance and utilize enough movement variation in our training to give us confidence in our programming overall.

Currently, we only have one kBox and one kPulley in our gym, as we feel flywheel training should be monitored for most athletes and not treated like an accessory movement. If, and when, we have more units, we may use the kBox for more general use and accessory patterns, but as of now our kBox training is like Olympic weight training or heavy barbell work— you can’t look the other way and hope it’s done well.

A PR doesn’t happen every day, but a standard should be set when using certain equipment, says @SPSmith11. Share on XThe kMeter is our compliance solution and creates a fail-safe way to ensure effort. Not only do we expect the efforts to look a certain way, but the output must resemble the athletes’ capabilities. If they reach a certain peak output on a good day, we should expect them to be working around or above that number to hope for anything meaningful to result. A PR doesn’t happen every day, and that is acceptable, but a standard should be set when using certain equipment. Let them know they need to earn the right to use it through hard work.

Can You Jump Too Much?

We used a lot of jumps and plyo work in our programming already, so it only made sense to see where we could include or modify what we were doing and take advantage of the tools we had. We are happy with our jumping progressions, but were initially concerned with the potential problems that could pop up if we added to what we were already doing. Due to the mechanics of the exercises, we assumed there would be a noticeable increase in patella- or Achilles-related complaints, but we have found the opposite is true.

We have used the kBox and kPulley quite successfully in reducing knee and Achilles pain in many athletes, and the incorporation of long, moderately loaded sets have seemed to help the most. There’s a reason they call the injury “jumper’s knee,” and what we learned this year is that decreasing jump training or reducing volume isn’t as effective as preparing an athlete to withstand the stressors they will face. In the winter months, when running in the grass isn’t possible for most athletes in the Northeast, a strong set of tendons pays off big time.

We have used the #kBox and #kPulley successfully to reduce knee and Achilles pain in many athletes, says @SPSmith11. Share on XFor the rehab or prehab side of flywheel use, in regard to jumping and avoiding knee issues, we move between starting off with flywheels and finishing with them. Some clients see better results when they “activate,” for lack of a better term, prior to jumping, and some do well with simply adding a good amount of volume to wrap up a leg day. When injuries, whether lower body or even upper body (collarbone or shoulder surgery), require removing jumps altogether, it is possible to replace them with lighter, faster flywheel work. It’s not even close to the velocity you’ll get with jumping, but the improvements you can gain in eccentric strength and propulsion are worth the inclusion.

Video 3. Athletes can use high velocity and various depths to elicit the training adaptations needed to make improvements in squatting and jumping. A light inertial load is great for athletes who are fresh but find plyometrics a little too demanding for the day.

Lastly, the flywheel can be used in complex or contrast training along with jumping to bring the programming to the next level. This, as I’ll discuss in more depth below, is a great tool for performance, but also as a means of reducing the number of actual jumps an athlete needs to do. By using the flywheel for the heavier portion and jumping for the faster portion of the contrast or complex, you can achieve the desired result without additional foot contacts or impacts. Some athletes will do both flywheel training and plyometrics with no signs of wear and tear, because the potentially hazardous loading of the knee and ankle is lessened without reducing the amount of necessary stress on the tendons as a whole.

Contrast and Complex Training for Jump Performance

There is probably a more “cerebral” method of breaking down the programming, but we’ve simplified and refined the process with a basic decision-making tree. This is just an option of ours, but it’s likely the most useful one for other coaches.

- If an athlete lacks general strength, we don’t worry too much about complexes or flywheel programming. We can use both tactics, but not much beyond ensuring they are doing the exercises right and can perform other movements without any equipment.

- Athletes who can lift well with traditional barbells, but have poor eccentric abilities, will have a healthy dose of flywheel patterns. We typically see poor eccentric abilities in people who used to deadlift often and spent less time using squats, Nordics, or jumping in their training.

- Injured athletes who need to jump to compete are perfect candidates for complex or contrast work with flywheel training. Nothing beats a return to play program that actually improves an athlete’s performance, and isoinertial resistance can be a huge help in this process.

- Advanced athletes sometimes need to move beyond what got them to that point. Adding contrast/complex training is a normal addition to these programs, but at times it’s not enough. Flywheels can sometimes replace the majority of traditional movements when that small fraction of an improvement might make all the difference in an elite athlete’s training.

In terms of the actual training, there are many ways to skin a cat (what an odd expression). We try to use our testing and profiling protocols to determine what methods work best for each client. We often program the different methods in a block periodization scheme and use the appropriate tool for the current block.

During accumulation or heavy stress phases, we may use high inertia with low inertia contrast work, and during speed or peaking phases, we will probably program heavy fast work with jumps, as it applies more directly to our desired outcome. Here are the combinations we see as most useful in terms of general training and flywheel jump programming:

- High-Inertia Flywheel followed by Low-Inertia Fast Flywheel

- Heavy Work (Traditional Barbell or High-Inertia Flywheel) followed by Jumps

- Heavy Fast Work (Olympics or Loaded Jumps) followed by Light Fast Work (Jumps or Low-Inertia Fast Flywheel)

- RFD (Barbell/Strength or Squat Jump) followed by Rebound (Jumps or Low-Inertia Fast Flywheel)

All of these options are effective when programmed appropriately. We have experimented with clustering barbell RFD work with flywheel for advanced athletes, which seems promising. For now, the primary goal is just ensuring the flywheel training that is in a program is done well and consistently enough for our athletes. It’s easy to get caught into the minutiae of training, but you’ll never know when something works really well unless you experiment a little, and the experiments should last longer than a day (unless safety is the issue).

What About Other Exercises?

Nobody cares about training differently—they really just want to train better. The first question I had with flywheels is what did they offer that dumbbells could not? That point was already covered earlier in the science side, but with all of the other options, such as band assistance and eccentric drop jumps, why use flywheels to jump better and not true jump exercises? The answer is we will always use a mix of methods to get results, but we must decide what is a priority and what is nice to do in theory.

Nobody cares about training differently—they really just want to train better, says @SPSmith11. Share on XIf an athlete has good eccentric abilities but poor vertical velocity and poor capacity to generate a very rapid rate in force, we will spend more time training faster and less time on the ground with exercises that express speed. In our experience, the time frames for a kBox squat are too long to improve reactivity, but they do shape a large capacity to train reactivity more. To make things simple for a new coach, we just tell them the kBox bridges the gap well and it trains the redirection of momentum better.

Video 4. Contrast training is popular, but you’ll only know if it’s appropriate if you measure. Testing athletes after a set of flywheel squats on a force plate helps identify which trainees may respond better or could benefit from conventional training.

Regular plyometrics is a priority supplement to isoinertial training. The principle of specificity holds true with rapid sporting actions and flywheels won’t stand up to the test completely. It’s not that flywheel training doesn’t work if performed alone, it’s that it works best by tying other means of training together.

#Flywheel training works if performed alone, but works best when tied with other training means, says @SPSmith11. Share on XLoaded jumps are similar to fast kBox squats, but they are not the same. Regular plyometrics are much faster, and barbell movements may look similar, but they are not even close to the same when you look at the line plots of the force plate. Anyone can load a jump—making the load work for them better is what matters. Jumping is a skill, but just performing vertical jump testing may not make you jump higher like rehearsing sprinting does. Jump training, not jump testing, is the key to improvement. We jump. We jump unloaded, loaded, reactively, from a dead stop, paired with heavy work, and paired with flywheels. But the bottom line is, we jump.

One thing we don’t do is jump with elastic bands. It’s not that it doesn’t have some value or science backing it, it’s just not currently worth the investment, when it can easily be replaced by dumbbells/barbells/flywheels and some creativity.

Jump Higher, Farther, and Safer

Many of our athletes made great gains in their jump performance before we had flywheels or any fancy equipment. We know that athletes everywhere are making improvements without any tools, but it’s not just about improving. Athletes invest so much time and effort into training that it’s our job as the professionals to seek out the best possible outcome, not just acceptable progress. With only so much training time after school for athletes, or in the off-seasons with our pro guys, we want to make sure they are explosive and reactive when they land.

It’s our job as the professionals to seek out best possible outcomes, not just acceptable progress, says @SPSmith11. Share on XDon’t just add kBox training and expect it to do all of the work for you. We think screening eccentric abilities with jump profiling and training hard with the basics can make a big difference, but pairing exercises that have high speeds and unique qualities can be a huge benefit to an athlete’s program. We recommend using the kBox or a flywheel system for anyone seeking jump improvements and anyone who could use some quality strength gains (hint: that’s just about everyone).

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]