The neck will almost certainly be mentioned in any discussion or article spotlighting areas of the body which are underutilised (or omitted completely) in conventional strength training for athletes. A ‘shoulders down’ approach underpins most programmes, and while there is discourse about this omission, it has yet to result in consistent, confident, and rounded periodisation of neck training. This is not to underplay the value of work in this area, with multiple posts on this website providing valuable practical insight into approaches being used by strength coaches. My purpose, rather, is to highlight a lack of consensus or sustained longitudinal approach.

This absence is despite the benefits of neck training tending to be generally accepted. It appears likely that neck strength, endurance, and anticipation can be trained using simple methods, such as banded or harness isometrics (Hrysomallis 2016). Naish et al. (2013) demonstrated a reduction in neck injuries following the introduction of neck strength in juvenile rugby players, while greater neck strength was shown to be effective by Collins et al. (2014) in reducing concussion. Given the potential complications of injuries to the neck, and from concussion, any modifiable risk factor is potentially a crucial opportunity to protect athletes.

In addition, it seems likely that technical coaching of sports-related tasks like heading in soccer or tackling in American football, rugby, or Australian Rules (particularly relating to tackle height and head position) may provide athletes an alternative technique for absorbing energy through the neck and shoulders, which could reduce upper quadrant injuries and concussion.

Challenges in Neck Rehabilitation

The net result of the ongoing discussion is a general acceptance across sport that neck strengthening should have a role and would be a worthwhile pursuit. Unlike other areas of strength training, however, principles of this training have not yet been fully explored. In addition, this knowledge gap is heightened following injury, where restrictions may be placed on the athlete and precision is required to avoid worsening an injury. While injuries to other body parts follow established guidelines—particularly in terms of progression and criteria-based rehabilitation to guide exercise selection and clearance for return to play—these simply do not yet exist for the neck.

Sports rehabilitation often relies on established strength and conditioning practices to dictate reconditioning periodisation, but in the absence of clear pathways, considerations for exercise selection for the neck tend to be narrow and general. In many cases, the only strategy utilised are low load, control exercises for the deep neck flexors—perhaps using a band, or perhaps not. This leaves a vast, unexplored chasm to bridge the gap between such exercises and the chaotic demands placed upon the neck in sports performance.

While injuries to other body parts follow established guidelines, these simply do not yet exist for the neck, says @fearghalkerin. Share on XTesting the strength of the neck muscles is useful as a tool in attempting to predict, prevent, and rehabilitate injuries, allowing this previously unknown variable to be quantified. However, the modality commonly used is an isometric test from a neutral position. Such testing—though clearly worthwhile—only provides clues as to a single component of neck function. This omits a variety of contraction types and positions, as well as the challenges posed by the randomness of sport-specific positions. Relying entirely on this data for neck rehabilitation would be comparable to only using isokinetic knee extensor torque in knee rehabilitation in order to gauge return to play. Or more precisely, a strategy that focuses on this position alone is akin to omitting plyometrics, running, or change of direction training following an anterior cruciate ligament injury.

This simply would not happen at other joints where there is higher injury frequency (such as the knee or ankle), since wide-ranging testing procedures, protocols, and variations in training approaches already exist. This situation highlights the importance of developing expanded rehabilitation pathways for the neck, where it is likely that a lack of familiarity may prevent the gap from being bridged between the early stages of rehabilitation and return to sport. Also, with such an approach, outcome measures must be developed that can guide return to sport clearance.

Assessment

It is beyond the scope of this post to detail the full assessment procedure following a neck injury, though it is worth noting the key points. The first principle should be to ensure the safety of the athlete, and this may require further imaging, investigation, or opinion. Often, range of motion is the first area to assess and treat. Small changes in range of motion can result in big changes in function and comfort, while also giving an indication of the level of the problem and the spectrum within which it is appropriate to work.

The first principle should be to ensure the safety of the athlete, and this may require further imaging, investigation or opinion, says @fearghalkerin. Share on XWhile getting an indicator of strength is useful, in most cases, during the initial stages it is most appropriate to assess the ability of the patient to recruit their deep neck flexor muscles in a neutral position rather than any kind of resisted or eccentric test, or outer range loading.

Assessment should include consideration of the scapulothoracic joint and shoulder, and addressing dysfunction—particularly around range of motion or strength in this complementary joint—may define the success or failure of the rehabilitation process, regardless of how appropriate a loading strategy is applied to the neck column itself.

Strategies aimed at local strength recovery of the arm, forearm, and hand may be indicated in the case of radiculopathy or compression or distraction injuries to the brachial plexus following a “stinger.” Hypertrophy training may be indicated if atrophy or wasting is noted.

Consideration should also be given to the kinetic chain, as this underpins athletic motion; being at the top of the chain as it is, the neck will ultimately be influenced by the actions beneath.

Global Overview

Another important early strategy is to give broad consideration to the athlete’s programme—particularly if the injury is not preventing them from completing running or strength training. As an example, pushing (for example, bench press) or pulling (chin-ups) exercises will challenge the ability of the neck to maintain cranio-cervical neutrality, so these can be considered a high load, isometric, neutral task for the neck. Consequently, it is worth considering if such exercises—with appropriate cueing—provide an opportunity to further reinforce the goals and messaging during rehabilitation. Alternatively, poor performance of these tasks may indicate that the synergy of the kinetic chain has failed (for instance, shoulder mobility, rotator cuff, trapezius, or abdominal dysfunction), and may be implicated in the initial problem.

Ultimately, the clinician should view every dynamic task as an opportunity for the neck to be trained. A global review of the athlete’s programme should be considered, allowing minor adaptations as necessary to provide training opportunities. This will allow an integrated approach to rehabilitation and for different aspects of the programme to complement others. For instance, change of direction mechanics during side-stepping will provide an eccentric, side flexion torque to the neck, which may irritate the athlete if they have not demonstrated appropriate range or capacity before carrying out the task.

Ultimately, the clinician should view every dynamic task as an opportunity for the neck to be trained, says @fearghalkerin. Share on XIt goes without saying that tasks such as tackling include an inherent risk to the neck, but as mentioned previously, strategies can be provided to mitigate these by improving technical proficiency. As a result, this too will prepare the athlete for returning to play.

Pathway

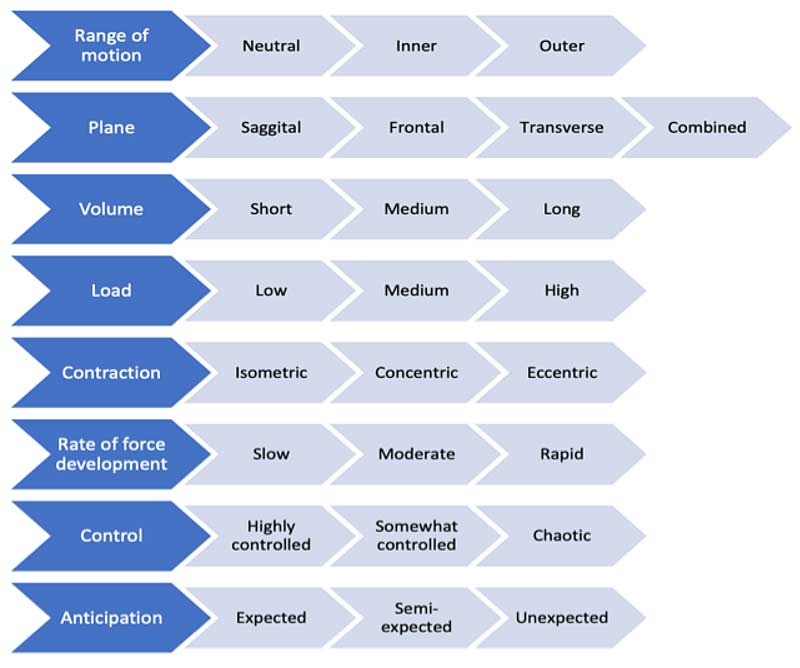

A progressive model is presented below which provides suggestions for how rehabilitation can be staged and progressed, with a consideration of multiple variables. The model is not meant to be a dogmatic hierarchy, given that the relative importance of some variables could be debated or interchanged. In addition, an athlete could achieve competence in one aspect before another one that is presented higher on the chart, and these factors may vary depending on the injury, training age, or profession of the athlete. For instance, if later-stage goals for an NFL player following injury are to withstand impact from opponents, perhaps even blindsided, several characteristics of this impact should be considered and trained for. The athlete may require great range of motion, in multiple planes, while producing rapid, high eccentric force following an unexpected collision.

Clearly, there are several challenges in replicating this safely in rehabilitation. However, it is upon the clinician to prepare the athlete for this by applying a step-wise algorithm.

Variables

An initial point to consider is the range in which training is carried out. The term neutral is used instead of mid-range, and range should be considered from a craniocervical, upper-, mid-, and lower-cervical perspective. However, most rehabilitation will begin in a neutral position to teach the athlete the principles of recruitment with low load, high volume, isometric neuromuscular control exercises. The deep neck flexors act as stabilisers during movements in each direction, meaning that once volitional control has been established, there are multiple options for progression of this prime exercise. Increasing the volume (longer repetitions or extra sets) or increasing the load are obvious options, but changing the range of motion to a comfortable point in range in a different plane is also an important component.

Once pain-free, isometric control at an appropriate duration or load is established at a point in range or plane, concentric training should be utilised. This may initially be done with a slow, controlled build up against manual resistance, before progressing to higher loads (for instance using a harness, bands, or plates). Caution must be used when introducing eccentric training, by again reducing and rebuilding the load applied, as change in contraction type has the potential to exceed the capacity of the neck and cause irritation, soreness, and setbacks.

As has been long established in the upper and lower limb, rate of force development is a core component of rehabilitation. This relates to the athlete’s ability to create force quickly, something that is protective in contact sports given the speed at which tasks are completed. Exercises where the athlete has to respond to a visual or audible stimulus and create force quickly should be used. At an appropriate point in range and low load, this type of training can be introduced relatively early in the process.

While the terms control and anticipation may seem similar, they refer to separate components of rehabilitation. However, they may both be thought of as higher-level aspects that require particular proficiency at most other competencies before being introduced. Regarding control, exercises that combine loading with movement of the body or extremities will challenge the athlete’s ability to control the task. For instance, carrying out a head-over-heels roll, grappling, or landing on a soft mat following a tackle will train the athlete in instances where they do not have control over the loads applied and the positions the neck will find itself in.

Finally, preparing for unanticipated loading is a crucial component of the process. While initially this may be low-load, manual pressure from varying directions, perhaps to a Swiss ball in contact with the athlete’s head, the athlete must ultimately be able to train feed-forward mechanisms to tolerate being blindsided in contact from an opponent—with direction and force that can equate to being abruptly rear-ended or hit side-on by a car.

Progression

The variables can be manipulated to provide a pathway for progression—for instance, while first increasing the range in which the athlete is applying load, the clinician may simply reduce the load. If they are introducing eccentric loading, they may ensure that it is anticipated, controlled, and at a demonstrably safe range. Progression then can be gauged by the introduction of these progressive tasks, which will relate to the demands of sports-specific tasks. This allows clinicians and athletes to clearly identify the importance of an exercise on the road to match play.

The challenge in many cases is identifying key performance indicators that ascribe confidence that the athlete is now competent at each stage of progression, says @fearghalkerin. #NeckInjury Share on XThe challenge in many cases is identifying key performance indicators that ascribe confidence that the athlete is now competent at each stage. However, if considering neck strength testing with a strain gauge, this could be assessed at different ranges, contraction types, and different levels of anticipation. Similarly, symmetry could be assessed, or simply successful task tolerance may be an appropriate gateway for progression.

Moving Ahead

A lack of established guidelines around neck training have resulted in a knowledge vacuum that is particularly notable around post-injury rehabilitation. The clinician or coach then requires an understanding of the competencies that challenge the neck, so these can be included or mitigated against during training and reconditioning.

This post has attempted to provide a framework that allows for the progression of exercise across multiple domains. By combining alternate progressions, there can be confidence that rehabilitation is being advanced at an appropriate speed. Lastly, by understanding where these competencies exist in a rehabilitation spectrum, key performance indicators and criteria can be agreed upon, which may guide at which point the athlete progresses to advanced tasks including full contact and match play.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Collins, C. L., E. N. Fletcher, S. K. Fields, L. Kluchurosky, M. K. Rohrkemper, R. D. Comstock & R. C. Cantu (2014) Neck strength: a protective factor reducing risk for concussion in high school sports. J Prim Prev, 35, 309-19.

Hrysomallis, C. (2016) Neck Muscular Strength, Training, Performance and Sport Injury Risk: A Review. Sports Med, 46,1111-24.

Naish, R., A. Burnett, S. Burrows, W. Andrews & B. Appleby (2013) Can a Specific Neck Strengthening Program Decrease Cervical Spine Injuries in a Men’s Professional Rugby Union Team? A Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 12, 542-550.