When is it time for your high school athlete to begin adding weight to the bar? When is it time to stop adding weight? These topics are often discussed, but they’re not often written about.

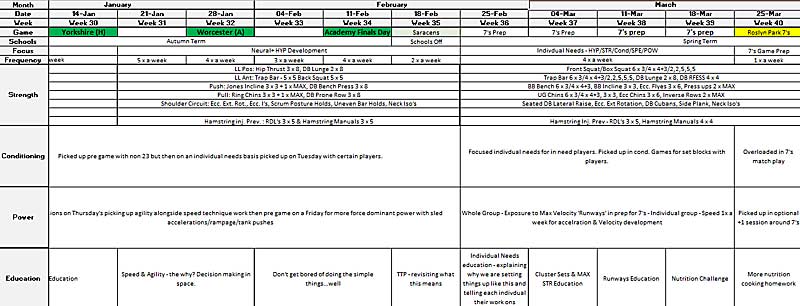

Over the last year I have written a series of articles describing the athlete layering process we use at York Comprehensive High School. In those articles I have gone in-depth into our body weight/load ratios, which are a big factor in dictating the steps of our vertical integration program. I have detailed our progressions and how we advance our athletes from an exercise standpoint. However, I have not really laid out our plan to advance our athletes from a progressive overload point of view. This article will explain how we use the most basic and simple concept in sports performance to force the adaptations we desire from our athletes.

While we can’t deny that progressive overload is a simple concept, in my experience it’s often only looked at from a load perspective. I truly believe that one of the most overused terms by sports coaches is “we need to get stronger.” While that is often a true statement, it doesn’t always fit the individual athlete’s situation. However, it is a universal phrase that most of us have heard ad nauseum.

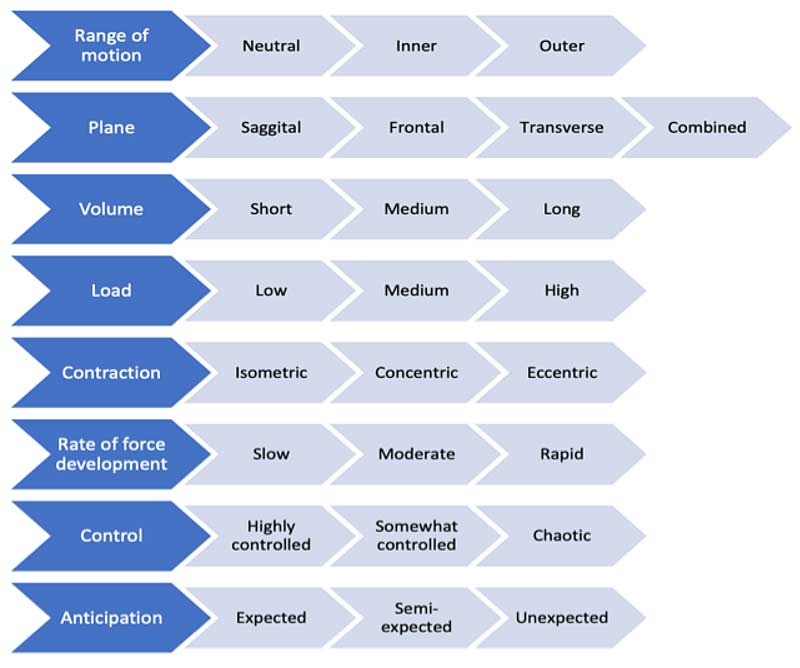

Load being moved isn’t always the best way to force adaptation in our athletes, but it’s the most commonly understood one, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XLoad being moved isn’t always the best way to force adaptation in our athletes, but it’s the most commonly understood one. I will take a look at how high school coaches can expand on that highly important, but sometimes overutilized, aspect of the concept. I will also go in-depth into how we use multiple ways to force progressive overload in our athletes at each layer of our block system.

Many Paths to the Same Destination

While adding weight to the bar is the most common form of progressive overload, there are many ways to skin that cat. We can all agree that younger athletes need to be taught the best movement patterns and techniques possible before we begin adding weight. How do we get to that point? When is it time to permit the athlete to load the bar? When is it safe? What are we looking for from the athlete before we do so? Let’s dive into those questions.

First Off: A Word of Warning

I will give you one piece of advice that I have learned the hard way over the years: Don’t be in a hurry to load a young athlete. Somebody once asked me what my biggest mistake was as a strength coach. That answer is as simple as progressive overload; pushing athletes who are not proficient movers to load weight on the bar because MY ego wanted to see it. If you do this, your athletes will suffer.

I look back over many years of coaching and cringe at things I did as a young football coach trying to learn the art of coaching. Do you want the strongest 15-year-old sophomores in the league who will probably suffer a greater number of injuries because they were pushed too soon? You can absolutely have that using progressive overload and loading up the bar. Wouldn’t you rather have the healthiest, most powerful, and available 16- and 17-year-olds? Be patient. Learn from the most common mistake I’ve seen in my 21+ years of doing this job. Your ego can cause life-long damage to kids. Be patient!

I will give you one piece of advice that I have learned the hard way over the years: Don’t be in a hurry to load a young athlete, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAs discussed above, the most common method of progressive overload is probably the use of increasing load. It’s really so simple that anyone can do it. This is a great thing but also a curse at times. Because of the ease of this method (especially when combined with the anatomical adaptations that come so easy to teenage athletes), every coach who has ever stepped in the weight room seems to believe they are an expert in the field of strength and conditioning. I actually had a head football coach who told me once “we were stronger before we started hiring strength coaches.” Well, that’s great…if we competed in powerlifting. I’m sure you had fewer concussions when the offensive coordinator was also the “athletic trainer,” but that’s not an ideal situation.

As we know, there is most definitely a point of diminishing returns from a strength standpoint. We are here to keep the athlete healthy while improving athletic performance. Strength is a necessary by-product but isn’t the only prescription.

As I told this same coach, making athletes stronger isn’t really that difficult. In fact, I could teach a five-year-old to take athletes into the woods and tell them to pick up a rock today, repeat but pick up a heavier rock tomorrow, and do this for six weeks. Guess what? The athletes will be stronger. If your claim to fame as a strength coach is “I make people stronger,” it may be time to hire a sports performance professional to help you out.

Basic Variations and Overview

I heard something at the gym in 1986 that rings true even today. I was 15 years old and learning how to train on my own. I had a guy at the gym describe progressive overload to me (many years before I knew what that term meant!) by giving me this advice: “Every day you come in here, add a small amount of weight to the bar and do five reps. When you get to a weight you can only do four reps, use that weight until you can get six again and then add 5 pounds.”

That launched my lifelong journey into human performance. That simple advice covered two of the four ways I use progressive overload today: load and volume. We have already discussed load. Everyone understands that one. Volume is, in my opinion, the second most prevalent way to pursue adaptation. You could use the same weight forever and just keep adding volume, and you would continue to adapt. The body is in a constant state of adaptation. The test for us as coaches is to understand what specific adaptations we need for maximal increase in athletic performance.

The body is in a constant state of adaptation. The test for coaches is to understand what specific adaptations we need for maximal increase in athletic performance, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XUsing volume can be a very efficient way to progress our athletes, particularly in the novice and advanced stages that sandwich the major strength-building cycles. The third variation we use to force adaptation is time. The faster you move a load, the more power you develop. We use velocity-based training in our program on a regular basis. Power=Force*Velocity is a formula and a scientific law. Using bar speed will result in the progressive overload of your athlete.

The fourth variation we use is time. An example would be to give an athlete 10 seconds to do as many reps as possible at a certain load. When the reps done in that time frame go up, add some weight and once again…adaptation.

Now that I have laid out the basics, it’s time to get into how we use these protocols within our block layering system. What and when signals us to add weight to the bar? What signals us to stop adding weight and use velocity?

Block 1 New Lifter (Freshman) Athletes

As we begin to transition our athletes from Block 0 to Block 1 (ideally in the summer between eighth and ninth grades), the main focus of our program is technical proficiency and teaching intent of movement. Load is a very secondary consideration during this time. Again, I need to reiterate that patience is a virtue during this period. You will have a wide variety of maturity among the athletes who come to you at this point. Just because an athlete looks 16 or 17, it doesn’t mean they have a training age to go with that.

For the sake of the athletes who trust you and depend on you, make them earn weight on the bar with an extended period of movement practice. Our first step with this group is to review the basic movements using bodyweight that we taught in Block 0. Next, we preload or assign a very light load to each movement. It’s important to remember that, at this age, anything they do will result in improvements (be patient).

For the sake of the young athletes who trust you and depend on you, make them earn weight on the bar with an extended period of movement practice, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XFor this article, I will assume that we are working with a group that has graduated from our Block 0 program. Below is the final step in exercise goals we set for graduation to the three main movement variations we use initially in Block 1.

Once we have technical proficiency in these areas, we begin our 5×5 program using these exercises. Step 1 is coach-loaded bars or assigned. The one caveat here is that, for us, athletes must earn the front squat with mastery of the goblet squats. This means our athletes all move into that movement at their own pace.

A second small adjustment is we start many of our block 1 athletes on a plate-elevated hex bar deadlift. Once they show us that they can hold a strong position from top to bottom, we remove the elevation. Once again, you see the patience we have with our athletes. Our motto is: Give them what they need, not what we want them to have.

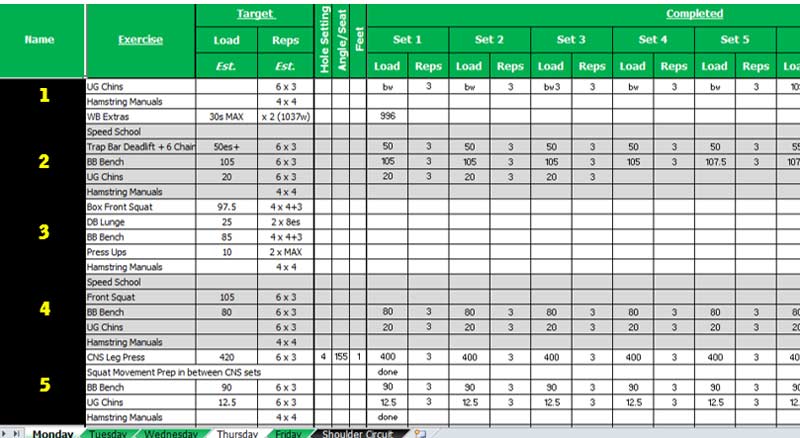

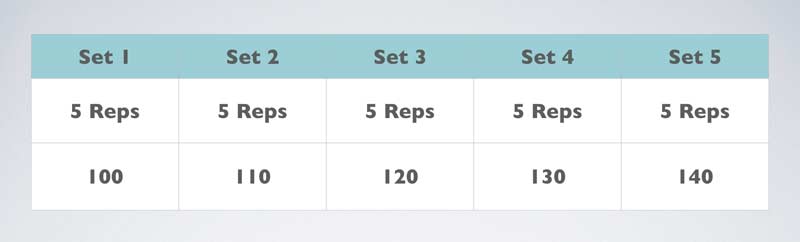

Let’s take a closer look at the hex bar deadlift. On day 1 for a graduated to the floor athlete, we load each bar with 100 pounds. This is an extremely light weight for most athletes, but we feel it’s a place we can start where all of our athletes will be successful. Once the athlete completes all 25 reps with 100 (usually that day), we add volume. The following session they will complete five sets of 6, then five sets of 7, and finally five sets of 8, all with the same load of 100 pounds.

This is the time we teach them intent and use our coach’s eye to coach technique and breathing. I will say that, in a few instances, I have allowed athletes to move to 140 during this initial four-week period. Use your coach’s eye. I will not allow any athlete to go above that load during this initial four-week period.

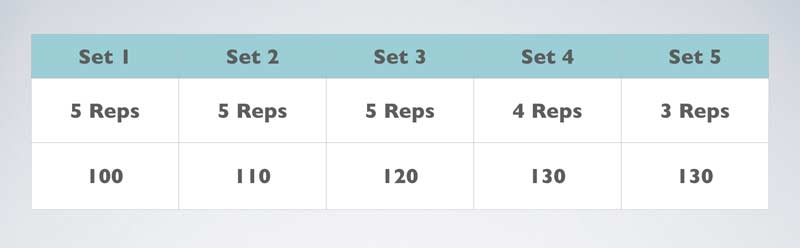

In the second block we begin to vary the load while still using our volume plan. We go back to our 5×5 but now have the athlete begin at 100 (or 140) and add 10 pounds per set as long as they hit the reps. For example:

In the scheme above, if the athlete misses any rep, they will stay at that weight for the remaining sets. An example of this:

The athlete above would then repeat this same scheme until they are able to complete all the reps at the designated load.

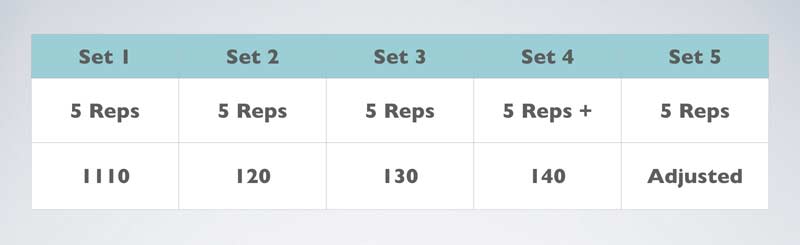

If the athlete completes the entire program at the designated load, that tells us it’s time to add a little weight. We slowly move from a program where volume is the main consideration to a load-based program. For the week following the completion of the last set of 5 at 140, our athlete’s sheet would look like this:

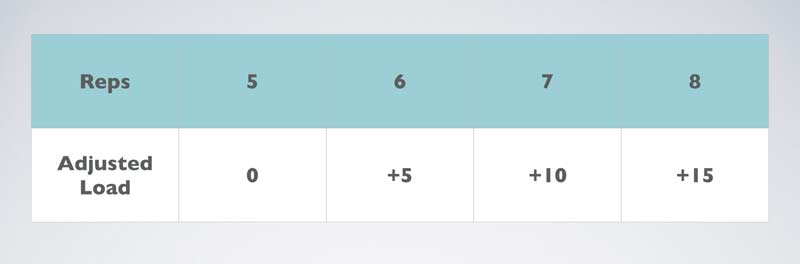

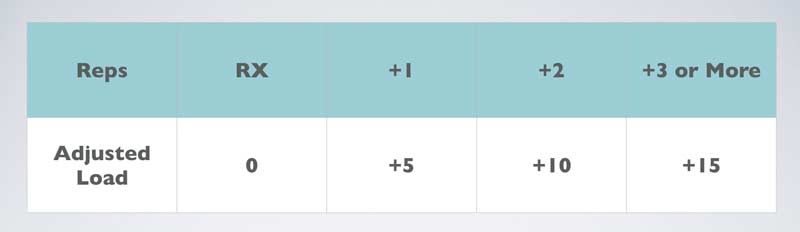

You see that we have added a “plus” set to begin to take individual performance into consideration in the loading process. The plus set gives the athlete the opportunity to go as far as eight reps in the fourth set and use the chart below to adjust the load for set 5.

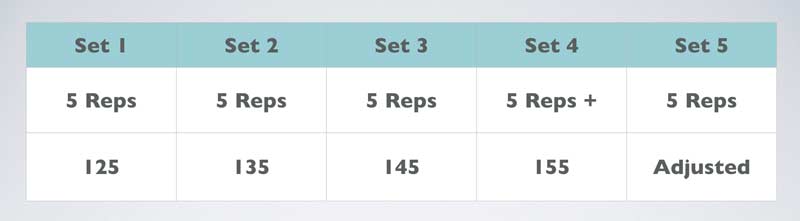

We now reach a point where things begin to take off. Our athletes begin to work toward the percentage-based programming they will graduate to in Block 2. Let’s say the athlete in question was able to hit 140 for eight reps (+3). They would then add 15 to the last set and attempt 155 for five on their final set. If they are successful, the fifth set weight will now go into their fourth set for the following week, and we adjust sets 1–3 accordingly. Here is their next week’s chart:

This athlete will again repeat the process of adjustment and could go as high as 170 the last set for 5. You can see that once we get to this point, the athlete is on track for successful strength adaptations.

One major note here: Only clean reps count. We DO NOT allow struggle at this point. Failure is not a goal here. Technique with bar speed is not to be compromised. This method has proven successful for us in balancing the teaching of technique and intent with the loading of weight onto the bar. We use the same basic progression for all three of our major strength movements. By the spring of their freshman year, most of our athletes are well-prepared and ready to graduate to Block 2 intermediate.

Block 2 Novice (Sophomore) Athletes

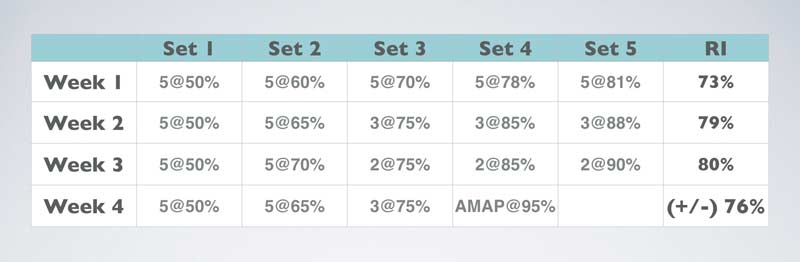

By the end of our Block 1 program, all of our athletes have a projected 1 rep max to work off of. The basic program is in the chart below:

We assign each athlete a training max that is 90% of their predicted 1RM to start. This ensures that our athletes stay in an intensity that allows max bar speed for transfer to sport (70–85%). So, when you see the sets at 88%, 90%, and 95%, keep in mind that those are based on 90% of the actual 1RM. As you can see, we use a traditional program with an inverse relationship between volume and intensity.

In Block 2 there is just one plus set every four weeks. As above, we have no interest in blowing up our athlete’s central nervous system with sets to failure. Our goal is moderate to moderately high intensity with great technique and at max bar speed. Transfer is always our No. 1 consideration for sports performance programming. So, the question of when we add weight to the bar is pretty simple during this block. We follow the plan.

This method has produced very good results for us, and I highly recommend it. Keep in mind the age of the athlete in this block. You do not need advanced techniques to force strength adaptations. Keep it simple and trust the process (and be patient). By the spring of their sophomore year, most athletes are ready to graduate to Block 3.

Block 3 Advanced Athletes

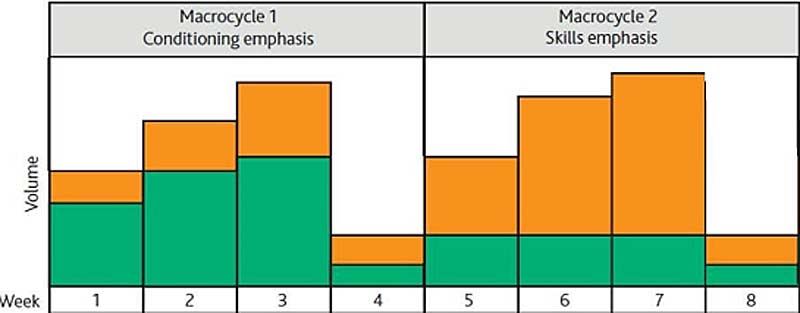

Our Block 3 athletes shift to yet another form of primary progressive overload. While we still use intensity increases to force adaptation, we now also use an undulating wave volume system as our primary path of progression.

We progress with a slow increase in volume of 10% (all reps over 50% for squats, cleans, snatches, RDL, presses, and pulls constitute the total volume) every four weeks. During this phase we use ranges of relative intensity for each major movement. Every four weeks the RI of each movement also increases 2% total for each movement. Our goal is to do 750–850 total countable reps with the vast majority in the 70–85% range by the final two phases.

While we still use intensity increases to force adaptation with Block 3 athletes, we also use an undulating wave volume system as our primary path of progression, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XWithin the four-week phase, we have one session that includes a plus set exactly as we do with our Block 2 group. This allows us to give a mid-term-like exam to our athletes at least twice between testing phases. In addition to this, we use our athlete monitoring system to initiate a conversation with any athlete who seems to be at a high level of readiness about possibly adding weight to set. At the same time, it can also lead to a conversation about lowering weight if the athlete’s readiness is not in a good place. This is where the art of coaching comes in. Know your athletes and use your coach’s eye to make every attempt to give them what they need when they need it.

Block 4 Elite Athletes

Not every athlete will make it to our Block 4 Elite program. In general, only my year-round, over a long period of time athletes reach this level. For that reason, a large number of football players (I see them 235 sessions a year!) and a smaller number of other athletes are in this group. The differences between Block 3 and Block 4 are not great. For the most part, it’s two major changes.

One is the use of velocity-based training and the bodyweight ratio for each individual athlete (also described in an earlier article). For our major movements, the main mode of overload is a combination of volume and speed. Relative intensity guides our load but the athlete’s bar velocity on a day-by-day basis dictates it.

The second difference is that these athletes have earned my trust to be able to adjust the weight using their perceived readiness in combination with meters per second. Here is an example of an initial back squat workout with our elite athlete block and VBT. This time the plus set is the athlete going until there is a 10% drop in average velocity and then adjust for set 5.

We allow the Block 4 athlete to choose what the adjustment set will be based on how they feel for that set, as long as they stay at or below the recommendation. In this case, the athlete could have added up to 10 pounds but chose just a 5-pound adjustment. Our online programming platform will note this adjustment and adjust this athlete’s predicted 1RM as well. Using VBT allows us to correctly adjust load for the specific adaptation we seek each and every session.

As you can see, the most basic and simple aspect of strength and conditioning can be used in multiple ways to force specific adaptations in your athletes. While the advice given to me as a young athlete about just adding a little weight each time is, without a doubt, progressive overload in its most pure form, it’s not the only road to take. When making decisions to allow your athletes to load the bar, remember that while overload is simple, your decisions should not be.

Give the athlete what they need, when they need it. Too many coaches pride themselves on “I can make them strong” egotistical chest-thumping and not enough on precision in programming. Making an athlete strong isn’t an achievement of great thinking and skill. That’s literally the easiest part of our job. The tough part is mastering the art of making athletes the best version of themselves they can possibly be.

Unless you only coach powerlifters, powerlifting protocols won’t transfer well to sport. Until they decide the winner of two teams tied at the end of a game by breaking out a bench and bar, stay focused on evidence-based practices designed to maximize your athlete’s ability to thrive in the arena they choose to compete in.

A presentation of this article is available at PLAE Academy, where you can collaborate with the author and earn a certificate of completion to apply toward CEUs.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF