Can I ask you a question, Coach? she asked.

Of course, fire away.

Are we ever going to do any actual conditioning?

If I were prone to conspiracy theories, I’d swear the kid was a plant—this conversation popped up after one of my June practices, just as online disputes were coming to a boil regarding Tony Holler and Brad Dixon’s Sprint-Based Football clinic, which set about challenging traditional views on conditioning and weekly training volumes for high school football.

This player, an incoming freshman, had just joined my multisport soccer team and with new players, the most common question I get is “why do we always jump so much?” The answer to that I have down: “To help you girls get faster, more explosive, and build resilience in a sport where a lot of kids your age get injured. And since no one’s ever taught most of you how to jump, if you leave my team able to hop, jump, backpedal, skip, and sprint, whatever else happens, that’s a win.”

The conditioning question, though, was a first because…my practices aren’t a walk in the park. But, like many teen soccer players, she was accustomed to finishing practices either spread out on a line and running gassers or knocking out laps around the pitch.

You’re not tired, I asked?

No, I’m pretty pooped, she said.

What did we do that made you tired, do you think?

Well, there were the sprints and jumps at the start and the passy-thingy and then the transition game was pretty tiring.

Right, I said. That’s the conditioning.

No, she said. But I mean conditioning-conditioning, like running after practice. Do we ever do that?

Conditioned to Conditioning

A few years ago, I interviewed Darcy Norman, Performance Coach with the US Men’s National Soccer Team, and he defined conditioning simply as: the ability to endure the demands of what is put in front of you. For many youth soccer players, what is regularly put in front of them are:

- Jogging laps before and/or after practice.

- Repeat “sprints” box to box or corner flag to corner flag.

- Line drills, gassers, suicides (whatever clever and catchy name you prefer to call COD sprints to failure).

- Sets of burpees or push-ups, either as punishments for failing to execute a technical, tactical, physical, or mental skill in the course of practice or just because burpees are hard.

Most 12-16 year-oIds do not have the natural ability to endure repeat sets of 20 burpees or 100-yard gassers or 20-30-40-50-yard repeat sprints. Soccer is a hard sport and running 100-yard gassers is hard and youth soccer coaches assume that if they can get their players conditioned for that second hard thing it will, by some clear-cut application of the transitive property, prepare their athletes for the first hard thing. And if those demands are put in front of the players practice after practice, over time, they will become conditioned to endure those practice conditions.

Soccer IS hard and running gassers IS hard & youth soccer coaches assume that if they can get their players conditioned for that 2nd hard thing it will, via the transitive property, prepare their athletes for the 1st hard thing. Share on XVideo 1. Here’s a routine attacking moment from one of my teams (high school freshmen and sophomores competing at a regional club level), selected not for anything noteworthy but instead because it’s a routine, recurring game action for this age level (mostly players who will be on their high school’s JV teams).

In that game moment, you see:

- A couple of 2-3 yard bursts.

- Backpedaling, quick/coordinated turns, and moving efficiently at various angles oriented to the ball or to teammates/opponents or to a gap in open space.

- An 8-10 yard burst into open space by the #11 (right wing) to receive a pass.

- The #10 (center-mid) makes a 30-yard run (accelerating ~8-10 yards at ~80-85% of her sprint speed) which is a result of her physical, technical, tactical, and mental abilities.

- (What you don’t see because it’s boring: after the ball ends up out of play, it takes 15-20 seconds to restart from a goal kick).

In that game moment—or, for that matter, anywhere in the entire 80-minute game—you ALSO don’t see:

- Anything that resembles players jogging a lap around the goal posts or much that immediately relates to steady-state running.

- Anything that resembles players running back-and-forth until their legs/bodies are at the point of giving out.

Those absent game moments were also what my baffled new player was missing—and, what she had been conditioned to: running for the purpose of achieving exhaustion/fatigue to finish a training session. She’s not alone—this is what a large percentage of youth athletes associate conditioning with and, if you ever take a fundamental NFHS coaching course, many of their warnings and “teachable moments” on the topic address the institutional pervasiveness of this type of conditioning.

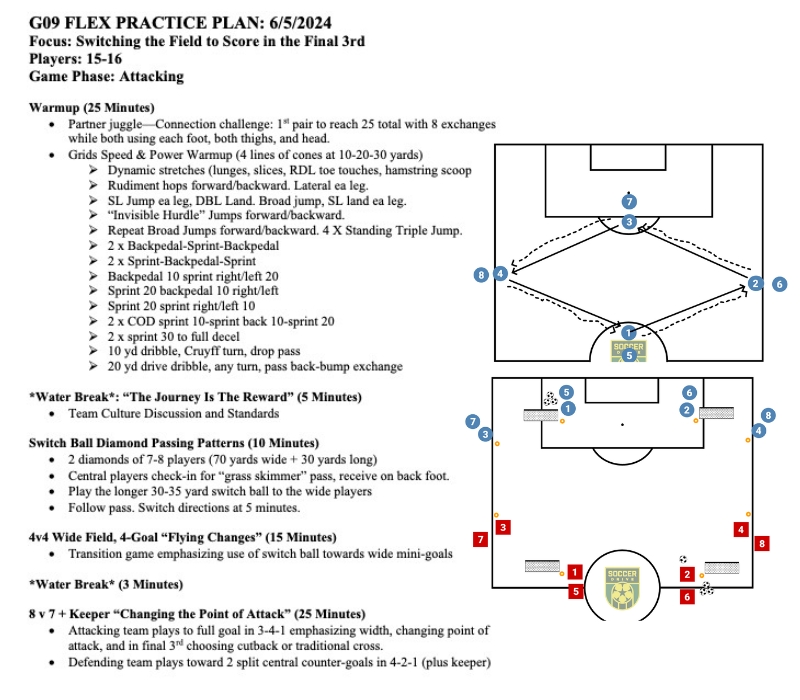

Here’s our practice plan from that June day that “appeared” to lack a dedicated conditioning element:

The demands placed in front of the players across the 90 minutes in this session are not easy to endure physically, mentally, technically, or tactically—the training session was meant to be fast-paced and challenging. And, it was meant to prepare players for the game moments they would not just need to endure, but those they would need to excel in over time.

In addition to game-relevant movements, as a matter of planned volume accumulation, the diamond passing pattern includes 4 x 35-yard self-paced jogs each rotation. 5 rotations each direction covers ~1400 yards and in 10 minutes of working on the day’s game-relevant focus skill, the players also accumulate ¾ of a mile of autoregulated running volume (Does this produce the same aerobic adaptations/cardiac benefits as steady-state jogging? No, I know it does not. More on that later).

What Is Speed In Soccer?

Whatever their current level, most youth soccer players have an opportunity at some point to also “play up” a level: an ECRL player guesting with an ECNL team, a G2010 player guesting with a G09 team, a JV player getting called up to Varsity for a game, etc. Upon returning to their normal team, inevitably, the first thing that player will remark upon is how much faster everything was at that next level of play.

What makes each next level faster? Well, first, faster players.

In addition to physically faster players, what makes THE GAME faster at the next level are that the technical, tactical, and mental skills are also a full click more advanced. Take the routine game moment shown earlier and instead envision an equivalent moment played out by my club’s G09 ECNL (national level) team or the Varsity teams at these players’ high schools.

What would be different outside of pure physical speed?

- Technical: Cleaner 1st touches in the initial transition moment—this would force the defensive side out of their compact shape and compel them to cover more ground at pace due to the ball moving more decisively (better possession also leads to the ball spending more time on the pitch and less time out of bounds, which leads to more total player actions and a “faster” feel to the game because of fewer stops/restarts).

- Tactical: A greater emphasis on closing space defensively—with more practice pressing and closing down balls, defenders at a higher level do so with greater intensity and purpose, which limits time/space for offensive players to make decisions. And attackers learn to create space with multiple types of runs to disorganize the defense—so rather than drifting toward a possible pass/cross, there would be more incisive and purposeful runs into gaps, forcing the defenders to react accordingly.

- Mental: More players “switched-on”—at every moment in the clip, 2-3 players are moving to be available for a pass, whereas with another year of development (and at the next higher level) 7-8 players should be moving to be active participants in the attack, and that anticipation/movement combines to create an elevated pace/electricity.

Being fit enough to endure a 40-minute half doesn’t matter if a player can’t play fast enough to get into the game for 10 minutes. So, how do you teach youth soccer players to play faster? Well, first you have to teach them to do the thing—they can’t do faster what they can’t do period. They can’t learn a faster/more efficient first touch if they can’t take a considered first touch unopposed, they can’t learn to make varied runs if they don’t know why to be a willing runner and where to make those runs, and… it’s hard to learn the difference between a game with everyone on the pitch switched-on and engaged unless they progressively gain more experience and learn to feel the difference.

From a developmental perspective—and youth soccer is developmental—being able to endure the demands put in front of them is not a useful skill until they are able to execute the demands being put in front of them.

From a developmental perspective, being able to ENDURE the demands put in front of them is not a useful skill until they are able to EXECUTE the demands being put in front of them, says @CoachsVision. Share on XFast AND Fit

My favorite pro soccer players are the most well-conditioned. Not the most technically-gifted, not the flashiest, not the biggest goal-scorers—I like to watch the ones who cover the most territory with the most competitive fire. Achraf Hakimi and Theo Hernandez on the men’s side, prime Kelly O’Hara and now Trinity Rodman on the women’s side.

In the 2024 Champions League semifinals, one of the most electrifying in-game battles was PSG’s Hakimi dueling with Borussia Dortmund’s Karim Adeyemi down the flank, attacking and defending each other from touchline to touchline with ludicrous pace and stamina. Though Adeyemi’s team came out ahead and advanced, Hakimi won the individual duel—each game in the home-away set, there was a definable “throw the damn towel” moment around the 70th minute where Adeyemi’s legs went rubber and he looked one firm nudge or stumble from going down for the count. He would be subbed off shortly after, looking relieved, having put in a truly heroic effort.

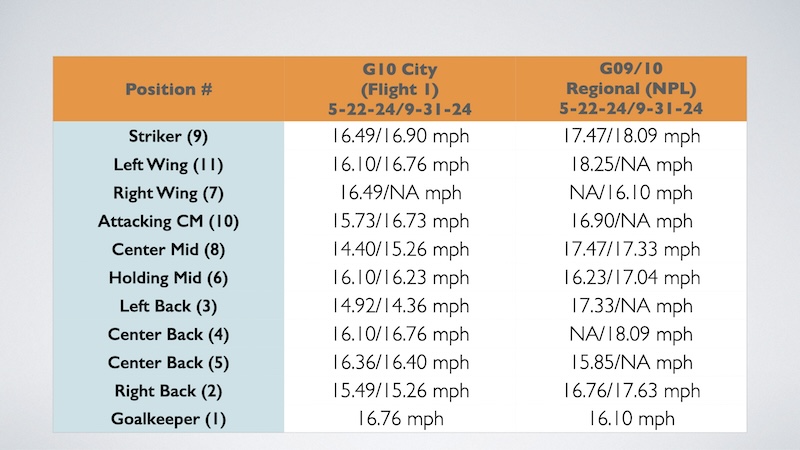

Hakimi has regularly been tracked at 22-23 mph in game actions and covers 8-9 miles in a 90 minute game (Theo Hernandez, meanwhile, averaged just over 10km p/match in the 2024 Euros). Let’s be very clear—when we talk about conditioning for youth or high school soccer players, we are not talking about the same thing as conditioning for an elite international player. When Darcy Norman and I have a conversation about the demands on our players, those demands bear very little resemblance to each other.

Any time online debates about conditioning become heated, most of those who criticize “conditioning” are specifically targeting old-school, Junction Boys-inspired conditioning to collapse—sets of 12 x 100s, line drills on a whistle, repeat suicides (again, the common practices that players expect and that the NFHS needs to continually warn coaches against in their educational materials).

Meanwhile, those arguing most passionately in support of conditioning tend to be advocating for soundly-progressed and carefully-monitored conditioning practices that are research-and physiology-based. Like elite international soccer vs. youth soccer, the practices being denounced and those being promoted… do not bear any substantive resemblance to each other.

For my own athletes, in previous articles and elsewhere, I have repeated my belief that any competitive athlete over the age of 10 should be able to roll out of bed in-season and run a 5k in 30-35 minutes without keeling over. Three miles is not far and a 10-12-minute mile is not fast (and yes, I get it, there are outliers in terms of lineman in football, bigs in basketball, and others for whom jogging 3 miles could be unwise due to body type, joint/tissue stress, other reasons).

How do youth athletes develop the capacity to endure a 1-3 mile jog? With limited practice time and the high cost to rent fields and pay for lights, jogging around the outside of that field for 25 minutes tends not to be the optimal use of time and money; but, that doesn’t mean you can’t put the demand in front of your athletes and provide the right encouragement.

If players live in California and attend a public middle or high school, they will need to run a mile in PE somewhat regularly. Encourage your players to run that mile with a competitive goal in mind vs. walking and talking with friends. If your team practices twice a week, encourage your players to use one of their off days to plan a 20-25 minute run someplace they find peaceful and enjoy running (a park, a trail, the beach, their neighborhood, wherever). Can’t run for 20 minutes? No problem. Run until they need to stop, walk for one minute, start running again…repeat as necessary for 20 minutes. Keep at it and keep trying to push the stopping point where they have to slow and walk until they can run a full 20 minutes.

A self-paced 2+ mile run has almost all upside: provides repetitive foot contacts that can improve general running form, develops the aerobic system to support all those other energy systems more frequently tapped into in soccer, enhances the parasympathetic nervous system’s ability to aid recovery, and improves overall cardiac health in ways that ideally become a lifelong habit for active kids to grow into healthy adults. All of these benefits will be more pronounced in a 20-25 minute autoregulated run than in 8-10 minutes of laps after a 90-minute practice.

What do MY Soccer Players Need to Be Conditioned to Endure? Common Factors that Impact Conditioning

One of the broader challenges with planning conditioning for youth soccer is that you cannot generally work backward from the game demands—those will vary wildly player-to-player and game-to-game, depending on:

- Speed and technical/tactical ability—Players who are faster, more confident, more technically-gifted, and more tactically aware will have more ability to impact the game and cover more ground in total than those who are slower and less impactful (and keep in mind, for those who appear slower and less dynamic, the issue is not that they are not FIT enough—it’s that they are not FAST enough).

- Position/Shape—Do you play a 4-3-3 or a 3-5-2 or a 4-4-2? A wide attacking player will have different responsibilities in different shapes…and even in the same shape, an outside back playing the #2 or #3 in a more conservative 4-3-3 system may cover less ground than a #2 or #3 in a more attack-minded one

- How long are the games and what are the substitution rules? A summer tournament game for 15-year-olds may be 2×30 minute halves and a fall regular season game could be 2×40 minute halves. Some leagues/showcases do not allow players who are subbed off to re-enter the game during the same half, while others do. Consequently, at a similar competitive level, some players need to be conditioned to play a full 40-minute half and others only need to be conditioned to play 20 minutes, rest 5 minutes, and then play 15 minutes.

- How big is the field? That same 15-year-old may play some games end-zone to end-zone on a full turf football field and others on a more compact 90 yard by 70 yard grass pitch. Turf plays faster than grass. Narrower fields have more balls out of bounds (down time). Fields rimmed by tracks have more out of bounds balls that then roll a distance (even more down time).

The biggest issues I see in youth soccer with coaches “conditioning” their players are that they are not working from the game in either direction. Instead:

- Volumes are fixed, excessive, and appear arbitrarily-chosen (12 sets of 100s!). The intensity is then not based on managing that volume, but is instead dictated by the coach shouting FASTER and PUSH like they are driving galley slaves to row harder.

- Conditioning is tacked on after practice with no connection to the volume and intensity of the preceding session…which may have already included a lot of high-intensity running volume.

- Outputs don’t resemble the sport in terms of speed, movement patterns, directionality, or duration.

- Lack of variation/fun—coaches have a lot of different names for suicides, but it’s all the same miserable line sprints.

Instead of working backwards, work forwards—develop players capable of executing your training session at pace. If they can’t? Here are a few things I like to mix in.

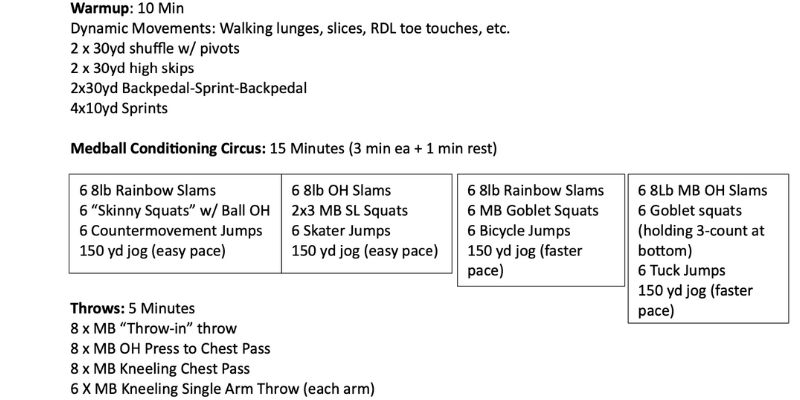

1. Off-Season/Early-Season Conditioning: Medball Conditioning Circus

Most youth athletes do not have an “off-season” where they drop everything and spend 3 months doing cannonballs at the pool, loitering around the mall, and playing video games.

But, if they’ve been traveling or there’s been a training gap of 2-4 weeks, general conditioning circuits are a very useful way to rebuild the stamina to endure the demands of their upcoming practices. I like these because for the athletes it feels more like skilled work towards a goal and less like a grind of mindless crushing labor.

2. Mid-Season: The World’s Greatest Sprinting Game

During our fall competitive season, there will inevitably come a dog-days of October stretch where we’re practicing twice a week and playing both Saturday and Sunday, the players are all getting slammed with other sports and activities, homework and tests, school dances and Friday night football games, all throughout one of the year’s longest unbroken strings of full academic weeks. Amid the all-of-thatness, I dial some things back to keep the athletes upbeat and engaged.

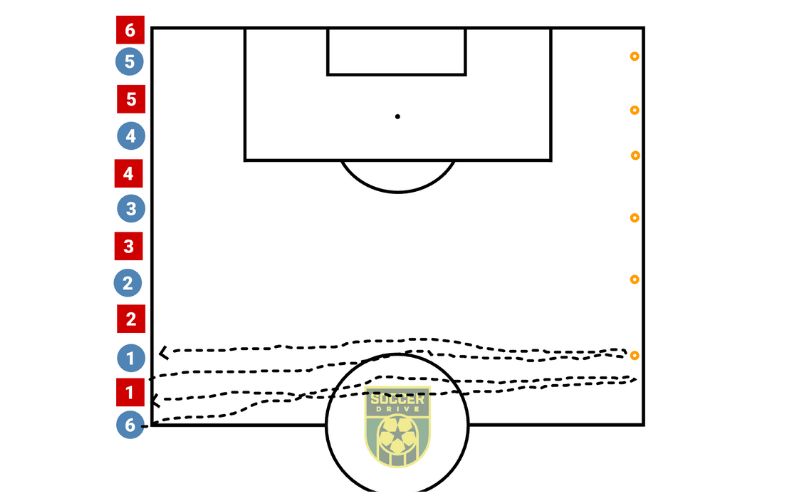

But, dialing back will, by definition, risk coming at the expense of being conditioned to endure the demands being put in front of them. At one time during this stretch, we’ll swing the opposite direction and wrap up an early-week training by playing “The World’s Greatest Sprinting Game.”

- Split into two teams of different colors and have the players alternate on one touch line. Set ½ as many cones as the total number players on an opposite touch line (50-60 yards depending on age/level).

- On “GO” players sprint across the field and try to retrieve an available cone. Every player must cross the opposite touch line whether they get a cone or not, and after crossing the line they immediately turn and sprint back.

- The first 3 players carrying a cone who finish across the original touch line score a point for their team. The last 3 players to cross the line lose a point for their team.

- Play 3 rounds with a rest period of approximately the time it takes you to re-set the cones.

Physical: Your fastest players will get the cones every round (I have never had a player finish in the top 3 but not have a cone), but getting back in the top three will vary round-by-round and the closing 10-15 yards will be very competitive among those players.

Mental: Your slowest players do not have to compete stride for stride over 100 yards with your fastest—their job is to push themselves to not be the weakest link, which is crucial in any “weak-link” sport. Not being in the last 3 is more a test of will than of speed or fitness and they’ll push themselves to do their role and not cost your fastest players the points they’ve earned.

Technical: Getting a step and running into the line of an opponent to beat them in space is a crucial soccer skill and also a key to success in being the players to get to the cones.

Tactical: Your fast and high Game IQ players will realize that winning all 3 races is unlikely…although this is a conditioning game, as a coach, it is gratifying to watch your fastest kids figure out how to WIN based on the established rules. The first round they may line up next to another fast player out of competition or next to a friend or at random, but in subsequent rounds they will purposefully line up in more tactical ways. They’ll start to talk strategy while you reset the cones—discussing with their teammates who should line up where, who should go all out for the point and who can save something in reserve for the next race while still not being anywhere near the bottom group.

At the end of three rounds, my girls will crash out on the field and look like Tony Holler’s 400m runners after a lactate workout…which tracks, since they will have just pushed to sprint all out for 360 yards in a matter of a few minutes. But, conspicuously, they end more on the giddy side of the exhausted spectrum than the broken side, still talking trash and knowing they’ve just competed through a hard thing. (Another conditioning game I started adding last year is the curved sprint variation of Drew Hill’s Infinity Tag from his Game On article—competitive, adds variety, self-regulating, and achieves a conditioning stimulus while similarly hitting positive instead of negative receptors).

3. Late Season: Beep-Test

Many high school athletes are anxious about conditioning tests, for all the reasons kids fear things: they don’t understand the way they will be conducted, they think it’s unfair to be tested on something that matters less than other important things, and if they fail they don’t want to be split off from the group and marked with that UNFIT scarlet letter.

Taking a judo approach to those fears, you can flip the Beep Test and use it as a conditioning means—for my club teams, I’ve done one during an early week practice at the tail end of the fall season, a couple weeks before the players have tryouts for the winter high school soccer season.

- Judo Move #1: Have the players all come check out the app or system you are using to run it. Kids like apps, as you may be aware. Explain the set-up and protocol very clearly so they understand they are not just there running blindly until they fall over.

- Judo Move #2: I have players from eight different high schools on my multisport team alone. So, I explain that WE are running it not as a test but as a confidence-builder and developmental tool just in case coaches at some of those eights high schools do use a version of the Beep Test in their tryouts or early season player assessments.

- Judo Move #3: Make this a team-driven activity and not an individual competition. They should all pace off each other, encourage each other, and once players begin dropping out, keep encouraging those still running. There is no consequence for dropping out and no threshold that MUST be reached.

It’s hard but not that hard—players who have been playing games every weekend and training regularly perform just fine and as a conditioning means, you can get a more upbeat and engaged 15-17 minutes of conditioning from running this one time than 15-17 minutes of just about any other form of running.

Okay, Coach, What Next?

Instead of working backward from the game, work backward from your understanding of conditioning. Does it come from an understanding of physiology and how to progressively develop energy systems to work in concert to meet a range of sport and lifestyle demands? Fantastic, carry on, you got this. Does it come from the old school WE WILL OUTWORK THE ENEMY coach you had back when you played in the 1980s & 90s who, in turn, adopted their approach from coaches they had in 1950s in an era when sport coaches were often WW II veterans who’d learned that boot camp methods could effectively turn unfit and unmotivated teenagers into an effective fighting unit (which, importantly, could reduce their chances of getting killed)?

Just like the demands of youth sports and the demands of elite sports don’t resemble each other, the demands of youth sports and the demands of close contact warfare don’t resemble each other either. Share on XJust like the demands of youth sports and the demands of elite sports don’t resemble each other, the demands of youth sports and the demands of close contact warfare don’t resemble each other either. In 10 years of coaching competitive soccer spanning 500+ games…I’ve never had a team that was physically, mentally, technically, and tactically superior but lost a game solely because our less-able opponent was better able to repeat their abilities over time while we could not endure the demands of the game.

My own understanding of conditioning falls into the dreaded it depends category because I fully agree with Darcy Norman, that conditioning is the ability to endure the demands of what is put in front of you and what is put in front of different players at different levels will be very, very different. One thing that is not different is that every soccer player trains to get better…and given that, by far the most simple and effective starting point I’ve found is Tony Holler’s imperative to “make practice the best part of a kid’s day.” Beginning there—with kids who want to show up and train with joy and purpose—over time, they will naturally become conditioned to what is being put in front of them.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF