Every year, training facilities review the best options for preparing athletes, and often consider investing in a treadmill or fleet of treadmills. The market exploded a few years ago with numerous options to train and rehabilitate athletes, and the birth of new systems has made what was once a simple process into one that requires a lot of research.

In this buyer’s guide, we list all types of treadmills, but only include those that are appropriate at the professional level, not consumer products or models that have no purpose beyond casual fitness needs. All products here are designed for athletes looking to maximize performance or fully restore their abilities after injury. We have included leading brands and example models that coaches and sports medicine professionals can choose from.

How Treadmills Are Designed and What Is Important

A treadmill is more than a revolving belt that you run on, and it’s dangerous to simplify the system this way, especially the higher-end instrumentation treadmills. Treadmill manufacturers have the challenge of creating a landing environment that is safe and effective to sprint and run on, and each model has benefits and compromises. When investing in a treadmill, it is wise to determine your training goals and then select the models that can fulfill those needs.

Judge a treadmill on its ability to interact with the user in a way that achieves training goals. Share on XPeople often base their investments on trends, which is fine for fitness facilities that cater to general populations, but that line of thinking is inappropriate for performance centers. Besides price and common purchasing decisions like warranty and durability, what matters is the design quality and the ability to create an interaction with the user that accomplishes the goals of training. Some treadmills are designed for rehabilitation, some for recovery, and some for sprint training. Each design has benefits and limitations, but when shopping for the right design, using the treadmill will likely be the final stroke before purchase.

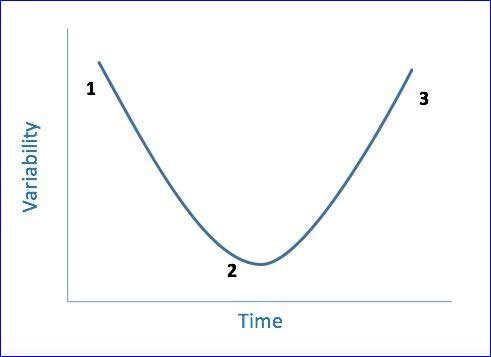

Four driving forces influence the selection of the right treadmill: the type of tread, its platform shape, whether it is motorized, and whether it is instrumented in some way. Nearly every treadmill has the ability to collect and share data, and most of the treadmills have a way to display the user’s output, even if it’s human-powered. The three major design factors are:

Human or Motor Powered: The most obvious difference between human-powered treadmills and motorized treadmills is whether the tread revolves from active contribution of the user or passive contribution from the motor and settings. Powered options are about delivering a constant and even velocity and human powered treadmills require very specific friction treads and designs to function. Motorized are sometimes more expensive, but a fluid motion without a motor mechanism isn’t significantly different in price.

Contact Shape and Slope: Treadmills currently have either a flat or a curved contact surface, creating a kinetic and kinematic motion unique to each model and user. Contour surfaces also help create horizontal friction, but these changes are still under investigation so the way they influence an overall training program is unknown. Additionally, the incline or decline qualities of a treadmill are common enough to consider when making a purchase.

Instrumentation Options: Often, treadmills with instrumentation use force plates for research or heart rates for fitness. Some instrumentation options use pressure profiles, and nearly all research options include camera additions for gait analysis or estimations in limb motion. Some treadmills have no direct instrumentation, but are designed to work in conjunction with external systems, especially with cardiac rehab and screening.

When reviewing systems, the quality of the design and manufacturing will obviously drive your final decision, but the priority should be on matching your intended training goal with the treadmill that delivers that benefit.

Training Effect of Treadmills

Treadmills are now considered both conditioning tools and speed development tools. In the past, most treadmill workouts were alternatives to running outside, but over the last few decades maximal speed and even acceleration have become mainstream approaches. Additionally, various forms of unloading, including underwater treadmills and suspension-type systems, have increased in use as the technology and awareness have grown. When investing in treadmills, those involved should decide the primary purpose of the treadmill and not expect it to be able to solve multiple functions beyond a few needs. While the velocity and incline are adjustable, most systems are designed for either continuous running or very short sprint intervals.

Conditioning, whether slow endurance type or longer intervals, is the primary reason that coaches and sports medicine professionals buy treadmills. Due to the convenience of observing athletes running in place and because they use small spaces, treadmills offer special advantages. Treadmills are also highly measurable, complete with onboard feedback of speed, grade, and duration.

Because return-to-play programs still have grandfathered protocols with treadmills, most institutions will buy treadmills to fulfill standard training programs. Cardiac rehabilitation and other medical needs rely on low-level conditioning with treadmills, but athletes in recovery perform simple walking sessions, especially combined with weighted vests and incline protocols.

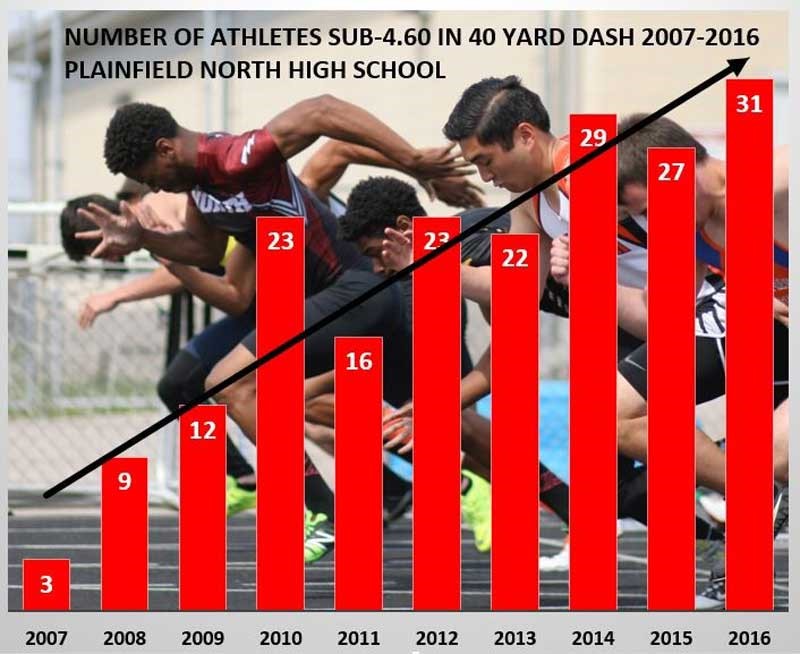

Speed training, whether maximal speed or short acceleration sessions, is the fastest-growing use of treadmills today. High-intensity interval training, or HIIT for short, is a sprint approach to conditioning and speed development. Due to the fact acceleration requires a rapid change in velocity, most HIIT programs don’t use motorized propulsion treadmills. Users can do intervals with steady speed systems by manual approaches that require them to literally jump into the sprint, but those approaches are often risky and are not typical outside of research or aggressive training sessions.

Speed training is the fastest-growing use of treadmills today. Share on XRehabilitation or similar needs like recovery can sometimes incorporate one or a combination of the above methods in training after an injury. Due to the controlled environment, treadmills are popular with rehabilitation, but multidirectional needs must be done on the ground. Aquatic and unloading options have become the new standard in rehabilitation, but conventional treadmills are more than relevant because they promote more natural running.

What the Science Says About Treadmills

Most of the concerns over treadmills is that the training on them will not transfer to the ground or that they will teach the body a movement strategy that will increase the risk of injury from a compromised motor pattern. Such fears are understandable for coaches and rehabilitation, but the research doesn’t demonstrate that anything significant can occur from temporary or partial involvement with treadmills. In general, training on a treadmill is a safe and effective way to improve both the performance and return-to-play abilities of athletes.

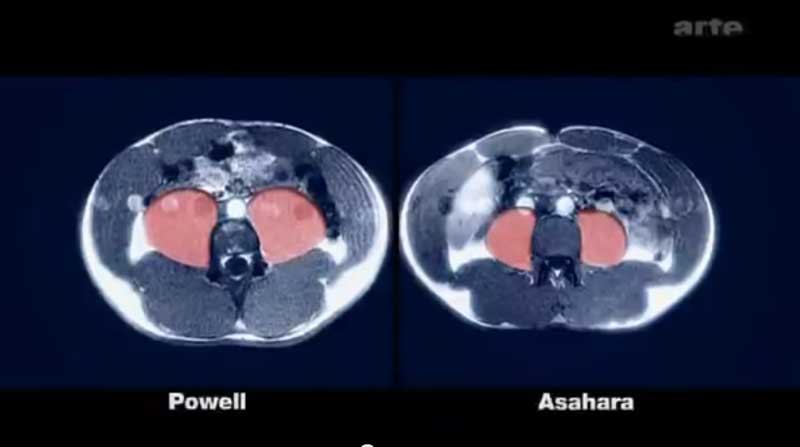

Kinetics: The most common request for instrumentation is force analysis, and nearly all research treadmills include a force plate. Based on the research, running on a traditional treadmill has very similar kinetic forces. While horizontal forces can be collected with treadmills, the issue is that a gradual postural rise does not exactly replicate what is done in sport. Note that acceleration kinetics have overlap, but they are not the same.

Kinematics: The movement on a treadmill during steady state conditioning running is nearly the same as on the ground running. While some differences exist, no research has indicated long-term adaptations that are unfavorable to normal ground running. In fact, most gait retraining programs have shown success in improving running mechanics.

Stride Parameters: Some changes in stride parameters exist, usually because the ground surface has a different elastic response than a treadmill. The differences are enough to note, but like the kinetics and kinematics, the significance is not a major impact for most programs that combine both land and treadmill running.

Energy Cost: Environmental factors, such as temperature and wind, cause outdoor running to have a higher cost than indoor treadmill running, but all being equal, the difference is not enough to make a major advantage or disadvantage. The pacing of treadmills has been a primary factor in the reason some athletes use them in training, including very contemporary programs such as triathlons.

Most of the differences in treadmills are in acceleration, and enough similarities exist to attain an assessment of the athlete’s overall ability and receive the benefits of HIIT. Clearly, treadmills are linear speed and linear conditioning options, so the limitations in agility and some sport needs are points to consider when deciding how to integrate them into a full program. It’s safe to conclude that treadmills are close enough to linear running to expect no worries in their value, but realistically they cannot do everything that ground-based activities provide.

Types of Instrumentation and Common Options

The acquisition of treadmill data, specifically training and recovery data, is a standard need for professionals in sport. It is the new normal, and users expect treadmills to offer instant feedback on speed and other variables. After exploring the right treadmill for training or rehabilitation, it’s then appropriate to get data beyond standard feedback information. Three key data types exist, and they all have specific roles in training and rehabilitation.

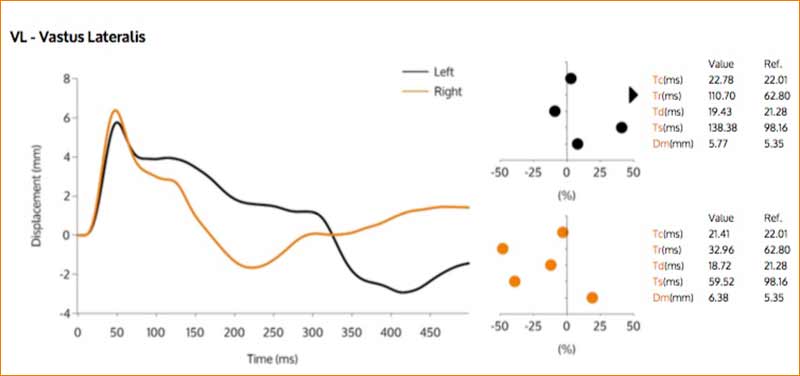

Force Analysis: Research and applied clinical settings use force analysis to detect dysfunction or study how forces interact in performance. Some veterinary settings have treadmills, as human performance is not alone in needing them. In addition to basic force analysis, in-shoe pressure and other sensors like EMG are usually added to reveal more information on the swing phase and how footwear interacts with the ground.

Conditioning and Aerobic Testing: Treadmill testing is common in exercise physiology labs and hospitals for everything from testing stress to assessing V02 max scores. Conditioning tests are usually sub-maximal, meaning they are done to a level that is fast or hard enough to extrapolate, but not so fast or hard that it causes complete exhaustion or failure. Blood testing and gas exchange measurements are very common, and simple heart rate tests are also used frequently. Finally, EKG and other advanced heart analysis uses treadmills to create repeatable assessments.

Gait Analysis: Most gait labs use a combination of video and motion capture to understand the motions of running rather than forces, unless it’s a serious research facility. Gait analysis is used to help retraining, be it a stroke or other injury. Some gait analysis can be done on a treadmill, but those are only walking, running, or jogging.

Beyond these three data types, not much else needs to be covered. External systems are available to acquire motion and aerobic profiling, but those systems are usually sold in bundled packages by distributors or sold together with company partnerships. Generally, force analysis is sold as one inclusive system, as the demands of post-production integration are too cumbersome and potentially dangerous to apply.

Leaders in the Sports Training Treadmill Market

More than 50 treadmill companies exist in the general fitness and consumer world, but sports performance and sports medicine are more demanding markets. About a half dozen leaders exist, all specializing in delivering a unique benefit to teams, colleges, clinics, and private facilities.

Motekforce link: A great example of a small company that specializes in instrumentation treadmills, Motekforce link is the Dutch option for those looking for a lot of data and extreme treadmills. Similar to other brands, they offer skating versions of their equipment. The company uses dual belts and customized software to provide a rehabilitation experience that is perfect for hospitals and clinics. While not a large brand, Motekforce link represents how options outside the box can succeed even in a crowded market.

WOODWAY: This giant in treadmills has two primary lines, the conventional sport option and the new “CURVE” solution. WOODWAY is a serious commercial player in the fitness space, and their larger robust options have been in professional sports for decades. WOODWAY offers hockey-specific versions of its treadmill, and the contour system it provides has taken off in elite sport training as a vertical running alternative to tempo running. WOODWAY brought a lawsuit against Samsara Fitness over their TrueForm Runner treadmill, and it looks like the CURVE will remain a unique feature over the next few years. WOODWAY also has a relationship with the WattBike, and can provide clients with sales and support with that indoor cycling option.

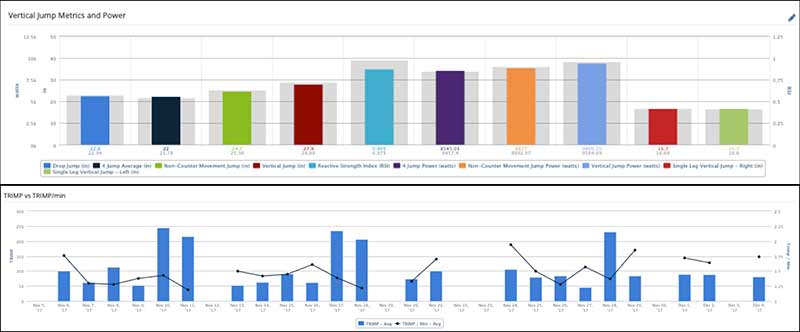

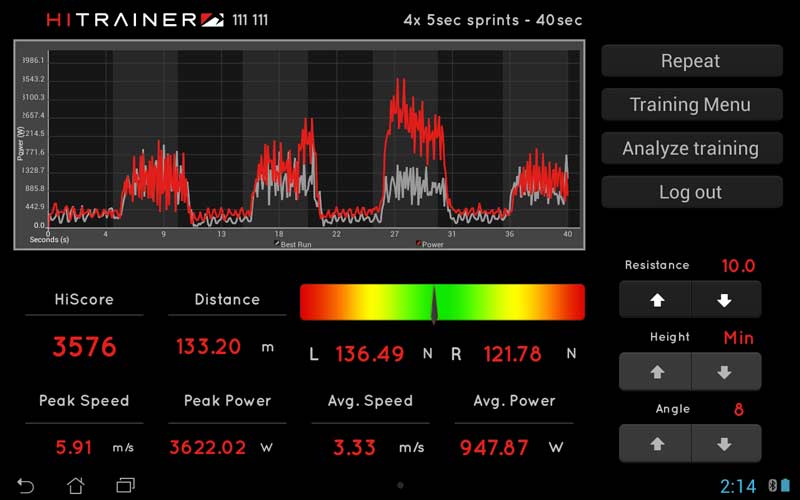

HiTrainer: The Canadian company has been a leading pioneer in treadmill metrics since 2008. Its self-propelled trainer can collect an athlete’s speed, power, balance, and even profile fatigue data. While they help athletes in elite performance, such as the NHL and NBA, you can now see HiTrainers in local gyms for the benefits of interval training. The source of its conditioning power comes from positioning the user in a full-time acceleration posture in order to engage the maximum amount of force production while running with variable resistance.

The HiTrainer is often used with HIIT training, one of the most efficient tools to peak your metabolism by stimulating mitochondrial adaptations and neuromuscular power. The capability of observing their power in watts gives users immediate and quantifiable feedback on the intensity of their workout. Finally, the HiTrainer belt offers very little momentum, enabling safe introduction to all clientele, including children and rehab patients.

Technogym: Technogym introduced a high-intensity option called SKILLMILL, and its position is that it provides multi-directional speed and power. One of the key issues with treadmills is they are walking or running devices, but the Italian company added rotational and backwards pulling motions to the product. In addition to the alternative forms of training, Technogym has a front mount that allows for a deep pushing angle for high-intensity work. In business since 1983, Technogym has sponsored multiple Olympic Games and was involved with Formula 1. It has a rich background in the consumer market as well.

AlterG: A major advancement with teams, the AlterG is a harness and unloading system that is extremely popular with rehabilitation due to the fact it can adjust impact forces. Using an air system that resembles an inner tube, the AlterG treadmill can help with rehabilitation and recovery by increasing or decreasing the involvement of an athlete’s body weight. A key issue with AlterG is its price point, but after a few years on the market, the system is more affordable and you can see specialized oversized versions of the machine in the NBA. The AlterG is now entering wider markets, such as senior care and hospitals.

Precor: The rise of CrossFit and Rogue Fitness created enough room for Precor to come in and sell a high-intensity training option treadmill. While the AirRunner Assault product is known as a simple solution for fitness, it’s common in CrossFit boxes internationally as well as other gyms. Similar to the AirBike Assault, the popularity of the treadmill is based on the raw design that requires nothing but a user to get on it and go. The system does have a wireless connection option as well as LCD display, but for the most part it’s a stripped-down treadmill ready to help drive fitness in the high-intensity crowd.

HydroWorx: This last treadmill is an underwater option designed to unload joints and mimic enough of the running motion to encourage similar adaptations. Known internationally for rehabilitation, the water treadmill is a common tool for easier workouts for distance runners, and is also important for return-to-play protocols. Underwater treadmills are popular for post-surgery, as they have unique benefits beyond the unloading of the eccentric forces, such as changes in muscle contraction and hydrostatic benefits for lymph movement. HydroWorx is a leader in sports aquatic recovery, and the underwater treadmill option is mainly for elite facilities, not very small facilities.

Each year, new treadmill players come onto the market, but with the limitations of design, we have seen challenges with IP and maintaining market share. Focusing on new advancements and how older models perform year after year is a great approach to balance innovation with the need for sustainability.

Investing in Treadmills – Where to Start

Nearly any major facility or team will eventually need to decide on a treadmill purchase, and these guidelines and list of leading brands are enough to help you make an informed decision. Coaches and sports medicine professionals who focus on the training response, key features, and data needed have the right decision points to move forward. It is perfectly acceptable to use different systems if needed, provided the staff or users commit to knowing how to operate and sometimes interpret data from sports treadmills.

The profession will decide whether desired training data will come from wearables or treadmills. Share on XIn the future, more and more data will be expected from training sessions, and the profession will decide if the information will come from the wearable market or by more instrumentation in the treadmill space.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF