After the huge success and popularity of the first “Jumps Roundtable” series of articles, SimpliFaster asked Coach Nick Newman to trade his usual answers for questions. Nick interviewed eight accomplished jumps coaches for the second edition of this excellent six-part series.

We will publish one question from the “Jumps Roundtable Edition #2” per day over the next six days. The fourth question deals with the reduction and management of injuries. Please enjoy, and please share.

The Coaches

Bob Myers: Bob Myers is currently retired, but served as Associate Head Coach at Arizona and was a college dean and athletic director over the past 40 years. He has an M.S. in Kinesiology, specializing in Biomechanics, and a doctorate in education with his dissertation on “A Comparison of Elite Jumps Education Programs of Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom Leading to a Level III Jumps Education Program in the United States.” Bob was inducted into five Halls of Fame as an athlete, coach, and athletic director. He has published 31 articles in professional journals around the world and has lectured at over 50 locations throughout the world.

In his 13 years coaching at Arizona, Bob coached four national record holders, five collegiate record holders, and 27 All-Americans in the high jump, triple jump, long jump, javelin, and heptathlon. He is perhaps best known for coaching the University of Arizona women high jumpers to a 1-2-3 finish in the 1985 NCAA Outdoor Championship, where all three jumped over 6’3” (1.91m for second and third, and 1.93m for first) even though two were heptathletes. He also coached Jan Wohlschlag, who was ranked No. 2 in the world in 1989, won four USATF National Championships, and was the World Grand Prix Champion.

Todd Lane: Todd Lane entered his 10th season as a member of LSU’s coaching staff in 2017. The Tigers and Lady Tigers have flourished in eight seasons under Lane’s direction—he has coached 11 NCAA scorers to 35 scoring All-America honors in four different jumping events since joining the LSU coaching staff right before the 2008 season. His student-athletes have also captured six SEC championships and 36 All-SEC honors over the last eight seasons.

Nelio Moura: Nelio Alfano Moura has been a member of national coaching staffs in Brazil since 1990, participating in five Olympic Games, five Pan-American Games, and 17 World Championships (Indoor and Outdoor). Nelio has developed, in partnership with his wife, Tania Fernandes de Paula Moura, more than 60 athletes who qualified to national teams, and he coordinates a talent development program successfully maintained by the São Paulo state government. He is Horizontal Jumps Coach at Esporte Clube Pinheiros, and has a master’s degree in Human Performance from UNIMEP – Piracicaba. At least one of Nelio’s athletes has qualified to each iteration of the Olympic Games since 1988, and he guided two of them to gold medals in Beijing 2008.

Dusty Jonas: Former high jump Olympian, Dusty Jonas, was named a full-time assistant coach on the Nebraska track and field staff on July 12, 2017, after eight years as a volunteer assistant for the Huskers men’s and women’s high jump. Since joining the Huskers program as a volunteer coach in 2010, Dusty has coached nine Big Ten high jump champions and 10 first-team All-Americans. Twelve Huskers have cracked all-time Top 10 high jump charts in his eight seasons. In the 2015 indoor season, Dusty helped then-sprints coach Billy Maxwell coach the Huskers men’s sprints, hurdles, and relays, and that group went on to combine for 46 of the team’s title-winning 127 points at the Big Ten Indoor Championships.

Neil Cornelius: After a torn ankle ligament at 19, Neil started coaching in his free time at the age of 20. One year later, he coached his first National Junior champion in the triple jump (Boipelo Motlhatlhego, 16.07m). By 2011, he had his first 8m jumper (Mpho Maphutha, the youngest South African and the first South African high school athlete to jump over 8m at the age of 18 years). By 2013, Neil has his first national colors by representing South Africa as a team coach for the African Junior Champs. There, his athletes received three medals (long jump: Gold; triple jump: Gold (15.98 CR) and Silver). In 2016, Neil coached Luvo Manyonga to an Olympic Long Jump silver medal (8.37m) and in 2017 to a World Championship Gold (8.48m) and an African/Commonwealth Record (8.65m).

Since Neil first started coaching, his training group has amassed 88 medals (16 medals at various international championships and 72 medals at national championships). He’s currently the head Long Jump/Triple Jump coach for the Tuks Athletic Club (University of Pretoria), as well as the head jumps coach for the Tuks HPC and the Tuks Sport High School.

Kyle Hierholzer: Kyle Hierholzer has most recently worked as the 2017 Lead Jumps/Multis coach and education manager for ALTIS in Phoenix, AZ. During the 2015 and 2016 seasons, he was the co-coach of Jumps/Multis with Dan Pfaff. Over the course of Kyle’s tenure, the group produced podium finishers at the U.S. Indoor Championships, World Indoor Championships, World Outdoor Championships, and Olympic Games, and also a Diamond League Champion. Before joining ALTIS in fall 2014, Kyle worked eight years at Kansas State University. Kyle primarily assisted head coach Cliff Rovelto in the sprints, jumps, and combined events. He also served as the primary coach for the K-State pole vaulters.

Stacey Taurima: Coach Taurima has been the Head of Athletics of the University of Queensland for almost five years, where he has coached senior and collegiate athletes to finals in World Youth, World U20 Championships, Commonwealth Games, and World University Games. He has coached national medalists in both senior men’s and women’s sprints events, and in 2017 coached Liam Adcock and Shemaiah James to Silver and Bronze in the Open Australian Championships, along with Taylor Burns and Daniel Mowen to Gold in the 4x400m. Stacey has coached 16 national champions and 19 international athletes in a five-year period and many professional sporting teams utilize him for his expertise in speed-based programs.

Alex Jebb: Alex Jebb is the Combined Events and Jumps coach for John Hopkins University. In his first two years of coaching there, his athletes have earned six All-American honors, five Academic All-American honors, 15 school records, four championship meet records, and two NCAA Division 3 All-Time Top 10 marks. Alex was honored as the USTFCCCA NCAA Division III Mideast Region Men’s Assistant Coach of the Year for the 2017 indoor season. He graduated from John Hopkins with a Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering and Applied Mathematics, and from Duke University with a master’s degree in Engineering Management. He is an engineer by day and coach later in the day.

The Question

Nick Newman: Injuries are often a necessary evil of elite performance. How do you prevent, manage, and alter your training around specific injuries? What important tips or information can you provide for coaches who have athletes that are often unable to tolerate the “ideal” training plan and always require alterations?

Bob Myers: Listen to the athlete, observe fatigue indicators, and keep an eye on total stress (school, emotional, social, etc.). Try to instill a daily working relationship between your medical staff, individual athletes, and the coach. Proper training and technical progressions are also critical in preventing injuries (such as developing a good background of plyometic work before moving to high-intensity plyometrics).

Regularly communicate off the track to keep your finger on the pulse of the athlete and make sure you are both on the same page. Every training plan is a road map; however, plans can change depending on injury, competition schedules, stress levels, etc. A great coach is one that can identify these issues (as early as possible) and adapt the training program to accommodate the athlete, while still following the overall intent of the program.

When athletes return from an injury, the training load must be adjusted downward. If possible, the coach should not skip ahead in the training program, but revert back in the training phase so the athlete has time to get back up to speed, or another injury is likely. For athletes who have a hard time following an “ideal” training plan (due to injury or other issues that may arise), keep in mind there is no “cookie cutter” training plan for each athlete. Plans should be individualized as much as possible, with as much data as the coach can obtain based on training age, medical assessments, and technical, physical, and psychological backgrounds.

Again, this is where the art or craft of coaching comes into play. No one program is the best for everyone and it is the experience of the coach, their communication with the athlete, and the rest of the staff (AT, PT, psychologist, nutritionist, etc.) that enable the great coaches to modify any plan when it is in the best interest of long-term athlete development.

Todd Lane: Certainly, sound training methodology would be the biggest goal, but when training groups, individualization is required. For me, variance in training is one of the keys in trying to alleviate injury possibilities. It’s easy to get locked into certain exercises and intensities. Varying these helps keep the body moving forward.

Variance in training is one of the keys in trying to alleviate injury possibilities. Share on XCommunication between the coach and athlete on a daily basis is key to the athlete’s health status and general overall feeling is HUGE. Tightness, aches, pains, etc., need to be discussed and evaluated. Training plans for the day should be altered if that’s what’s called for based on the athlete’s health. Often, it is the alteration of a single session and the athlete is fine.

If available, soft tissue work is the most desirable thing.

Every athlete brings some type of injury history to the table. If they get the same injury year after year, something needs to be figured out. Training needs to be set up to not only avoid the same injury, but also address and attempt to remedy the injury.

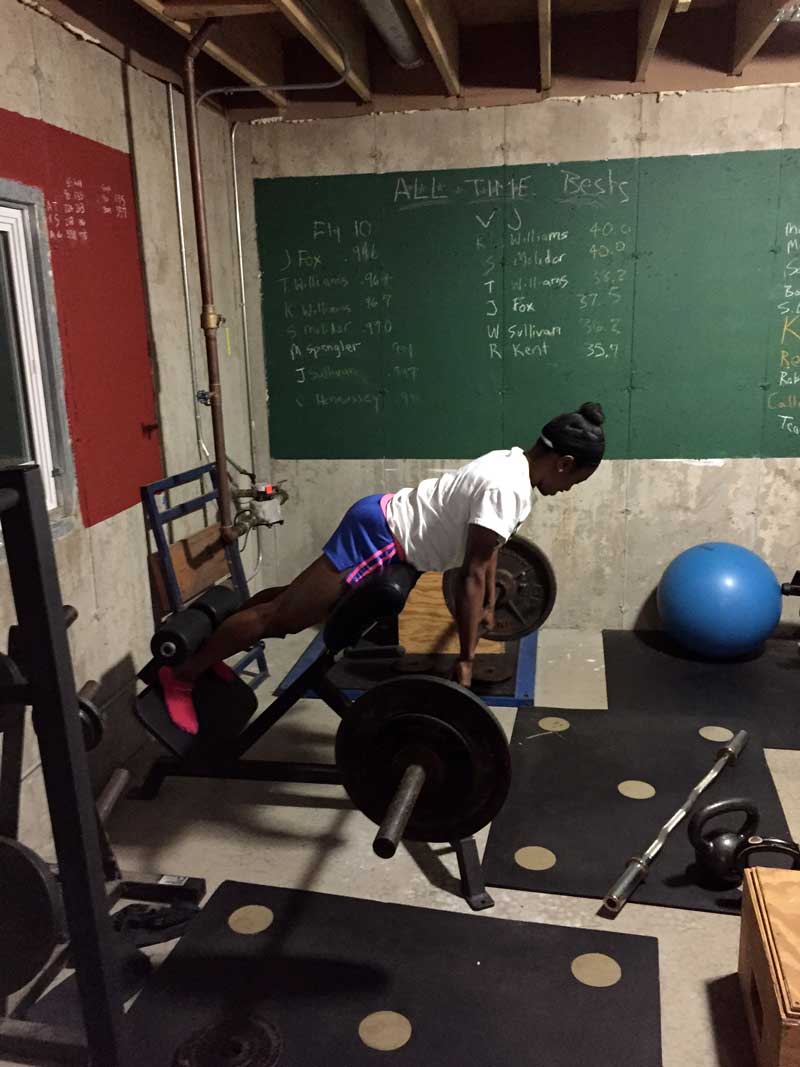

You go to Plan B, C, D, etc. I look at alternate training plans as to “what can I do to continue to feed the animal in a different way,” with the animal being the speed/power nervous system. Maybe it’s more time between the speed/power days to allow greater recovery. I can work through some injuries just by limiting the range of motion of certain exercises in the weight room or on the track. For example, cleans from the thigh instead of the floor, or bounding with limited flexion.

The coach needs to be constantly involved in rehabilitation programs performed by medical personnel. These programs often tend to be rooted in more endurance-type training and are far removed from the “feeding the animal” that I referred to earlier. I think a good rehab program has some aggressiveness in it and sometimes that means the coach needs to step in and employ training. I want the athlete back as soon as possible, even doing remedial work.

Nelio Moura: Injuries are really always part of the equation, unfortunately. This is particularly true when the athletes reach a level where they are able to express to the maximum their capacity to generate explosive strength. So, I am always trying to find a way to prevent injuries, with different degrees of success. I have noticed the best measures are the simplest: training in a smart way (paying attention to the ratio of acute to chronic load and avoiding load monotony, for example), good nutrition (real food is far more important than supplements, even though some supplemental strategies can be very helpful when guided by a sports nutritionist), and sleeping… two additional hours of sleep per day can make a huge difference!

I believe there is no “ideal” plan. Planning helps to organize the general actions taken, but changes should be made every day, considering the state of the athletes and the responses that they present. Systems of health and training load monitoring help me to implement those adjustments (the system that I use is AthleteMonitoring), but the coach must always pay attention to the athletes’ behaviors during practice, and we have to be open to listening to them.

Dusty Jonas: In a perfect world, no athlete would ever get injured; but in the real world of athletics, this is rarely the case. I think the best way to go about preventing injuries is with a well-designed training program that caters to an athlete’s strengths and improves upon their weaknesses. The first step in the process would be to identify an athlete’s deficiencies, injury history, strength levels, and movement patterns.

In the jumps, I commonly see tibial stress syndrome (shin splints), stress fractures of the foot bones, ankle sprains, patellar tendinitis (jumper’s knee), and the rare back or hamstring injury. Many of these are overuse injuries and can be avoided. Eventually, you start to get an idea about volumes and intensities that each athlete can handle without developing pain. Once armed with this knowledge, it makes planning for training much easier. Over time, you hope that athletes’ bodies adapt to training so that more volume or intensity can be added if necessary.

Some athletes will never be able to train in an “ideal” training program. You can design a program on paper with all of the best intentions, but in practice certain athletes always require alterations. What is considered “ideal” is relative to the athlete. Every one of them is an incredibly complex organism and all have different needs to develop.

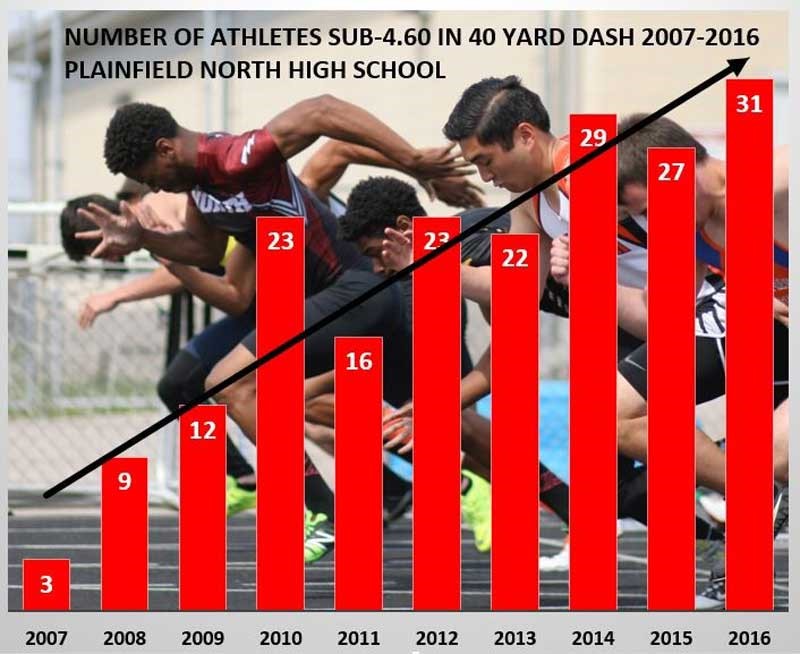

Some athletes will never be able to train in an ‘ideal’ training program—‘ideal’ is all relative. Share on XEarly in my coaching career, I assigned volumes based on what I had done or others had done in the past. I discovered very quickly that when I did this, many athletes ended up torn to shreds. Eventually, I learned that “ideal” is different for everyone and knowing what exercises, volumes, and intensities each athlete responds to best has helped me to develop much more specific training programs that have resulted in fewer injuries and more consistent performances.

Inevitably during an athletic career, however, an athlete will have an injury of some degree. The degree and type of injury will have a lot to do with how a management plan is designed.

If an athlete is able to train at some level, which is common with shin splints, adjustments to the training plan are made. Using shin splints as an example, rest generally resolves the issue. During this time, rehab exercises are done in the training room until the issue subsides. I typically prescribe limited weight-bearing exercises that mirror the theme of the day. Biking can be a useful option for running days as you can prescribe different tempos, speeds, and rest intervals. Doing running or plyometric exercises in the pool is also a great option and allows for better posture during a movement than a stationary bike.

If an athlete’s injury renders them unable to train whatsoever (hamstring tears or ruptured tendons, etc.), the management plan falls to the athlete’s training staff and their doctors/surgeons, if applicable. During this time, I find that communication is incredibly important between the athletic training staff, strength and conditioning staff, and sport coaches. I’ve seen and heard of numerous examples of athletes that got lost in the shuffle when it came to injuries in this regard. Having a return-to-play plan that involves all three parties allows for a better outcome for the injured athlete.

If an injury prevents an athlete from training like they normally would or removes them from training altogether, it can be a crushing blow to their psyche. I find that having a clear plan to move forward can help in this regard, as many athletes are process-driven creatures. Giving them small goals to achieve over a period of time can be a great way to drive the sometimes monotonous nature of rehab. I also think that having them involved with the team during training times makes them feel like they have not been forgotten and gives them a chance to look at the event from the outside, which can be a fantastic learning tool.

Neil Cornelius: Every athlete is unique and they will all need adjustments at some time or another, but keeping an athlete healthy requires a competent team. My success in 2017 would have been nothing without the physio, the psychologist, and the biomechanist being there. Having a team keeping the athlete healthy and conditioned allows me to do the necessary and important work on the track that is required.

If there are athletes always struggling with issues, it’s best to identify what those issues are (the majority of the time the cause of the long-term struggler’s injuries are away from the area of trouble), identify the source of the injury, and go out and address it. Whether that is changing your training program completely or getting outside help (another coach, physio, etc.), you do whatever you have to do. Adapting the training program to that individual is a must. Just remember that there are no quick fixes or results in athletics, and such a fix may take a lot more time than you or the athlete would like (a month, a year, two years, etc.).

Kyle Hierholzer: Injury management and prevention is the second biggest separator in high performance coaching behind mental resilience qualities. There are some common denominators among coaches who have historically performed very well in regard to this topic.

These qualities consist of, but are not limited to:

- Effective and consistent athlete debriefing (banging the drum here).

- Operating in an appropriate manner with support teams.

- Utilizing sound technical models.

- Designing programs with appropriate volume, intensity, and density ranges.

- Demanding high accountability in all areas.

- Making wise decisions in the moment regarding training adjustments.

- Maintaining an athlete-centered approach in all situations.

- Having multiple options for each training day… Plan A, B, C, D, etc.

Let’s spend some time looking a little closer at a few of these topics. The second quality on the list, “operating in an appropriate manner with support teams,” can be the most challenging component of managing athlete health. As coaches, we need the expertise of professionals across many fields if we truly want to give our athletes the best opportunity for success. These fields include: soft tissue therapists, athletic trainers, chiropractors, doctors, nutritionists, psychologists, life coaches, strength coaches, etc.

In many cases, the quality of care your athletes receive will be directly related to the quality of your relationships with these individuals. I recommend striving to create an environment where everyone in that circle feels safe to express their opinion, and feels that the opinion they have matters. You don’t want to have a critical piece of information left unsaid. This doesn’t mean that you must act on every piece of information received, but you don’t want anyone in the circle under-reporting.

We often see situations where each field creates their own silo, and then fights at all costs to protect their silo. This creates infighting, jealousy, “white knight” syndrome, poor communication, resentment, and frustration, and it is overall not a fun place to be. As coaches, we cannot blame anyone in that circle if we have not taken the time to educate them on what our expectations are for performance and professionalism. We must know a little bit about each component, and each component must know a little bit about what we are doing.

Dan Pfaff and Dr. Gerry Ramogida refer to this concept as “performance therapy.” The effectiveness of this concept is only as good as the quality of the relationships within the circle. As coaches, we cannot expect those relationships to simply happen because we happen to be in the circle. They must be developed, with safety, trust, and empathy as the hallmarks. If those qualities exist, then the team involved will work tirelessly to help athletes achieve success.

Coaches can lead on this. Be a leader. For more on leadership, I’ve recently become a big fan of Simon Sinek’s work. Check out “Leaders Eat Last” and “Find Your Why” if you are interested in some non-sport reading (which you should be).

The second of these qualities I will dive deeper into is “using a sound technical model.” This should seem like common sense, but unfortunately, it is not always employed. One of the biggest temptations we can have as coaches is to study and emulate the model of the world record holder, or the most recent world or Olympic champion. This can be very dangerous, as it can lead to a departure from a sound model.

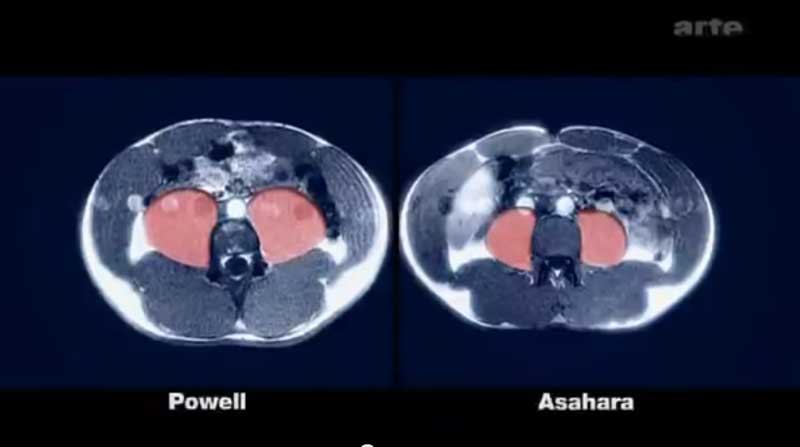

Many times, these athletes are outliers. There is literally nobody else who could or should use the unique model that they used. Also, we often don’t know the price those athletes paid for using these models. Athletics coaches have a professional responsibility to understand kinesiology, biomechanics, anatomy, etc. The more rules we break in relation to those topics, the higher the probability that injury will occur.

Will you coach outlier athletes who break those rules? Yes, if you coach long enough. Should everyone use the same model that your outlier did? No. How do we make decisions on when to allow athletes to break from sound technical models? When do we decide to change aberrant technique?

Try using the following questions as starting points before changing an athlete’s technical model.

- How long has the athlete been executing in this fashion?

- How proficient is the athlete at making change?

- Does the athlete understand the risks/rewards of changing?

- What is the quality of the therapy team’s ability to manage injuries?

- Is there something else we should change farther up the chain?

- Is the athlete physically capable of doing what we might ask them to do?

Finally, let’s discuss the last part of the original question regarding “ideal” training plans and alterations. I don’t think there is such a thing as the perfect training plan. If we think our training plan is flawless, then the only thing we can do is blame the athlete for not being able to execute it. This will create a toxic environment.

As coaches, we can individualize or “fine tune” our training plans in both the writing phase and during the implementation phase. In situations where an athlete is unable to handle the training as it’s written, that indicates to me that one of two things is probably going on. Either the coach and medical team are doing a poor job of adjusting training for that athlete on the day, or the athlete is doing a poor job reporting to the coach how they are feeling. Or both. Either way, it is the coach’s responsibility to address the situation.

Coaches should work to create environments where athletes feel safe reporting honestly. To do this, athletes need to believe that if they report a symptom, they will not be immediately shut down and sent to the trainers. This is where “decision making in the moment,” and “having a Plan A, B, C, etc.” come into play. We always try to find the closest thing to Plan A that an athlete can do before we remove them from the practice environment or intervene with a therapy modality. Over time, this creates trust and gives the coach more insight into how to properly prescribe training for that athlete.

We might be surprised at just how well some athletes can compete while doing what we consider to be Plan B training. Try using your workout plan more as a blueprint to drive big picture things you want to accomplish on the day or in a cycle. The correct implementation of that blueprint will be unique to your environment, style, athlete population, etc.

Stacey Taurima: Before we structure injury prevention programs, we need to know what we are preventing. Therefore, having a good understanding of the event requirements not only allows coaches to structure training programs to accommodate the event demands, but can also assist in mitigating possible injury risk.

Having a good understanding of event requirements can help coaches mitigate possible injury risk. Share on XModifying training programs to accommodate injuries can be challenging in the horizontal jumps events, depending on injury type. Creative programming and the establishment of solid medical/therapy networks both need to be implemented in the best interest of the athlete. Communication is paramount between all involved.

In my experience, horizontal jump athletes tend to express similar injury patterns to other speed/power ground impact sports such as basketball and volleyball, so, again, monitoring training load is vital in injury management and prevention protocols.

In the case of injury, we tend to do our best to remain as close as possible to the current program. We make modifications where necessary, but I like to keep the athlete close to the actual session plan if the athlete isn’t injured.

Again, depending on the injury type, we can duplicate training responses with other modalities such as bike or pool sessions.

Alex Jebb: For us, open lines of communication are the biggest factors in injury prevention. This goes beyond just asking the athletes how they feel before practice each day, as they warm up, and throughout the session. The athletes at Johns Hopkins are under incredible academic stress, and high performers will always put more stress on themselves as well. Since my main job is to develop them as people and aid in their preparation for careers and lives after college, we work around these stressors first and foremost.

It is normal for me to go around the room of athletes and ask how much each person slept the previous night. When I get answers such as “uhh…a couple hours” or “I promise to sleep tonight,” we make modifications to their workouts, such as swapping out a high-intensity day for a general recovery day. I can (and do) repeatedly stress the importance of sleep and nutrition, but I’m not naïve and I don’t necessarily disagree with them either—they’re at Johns Hopkins to prepare for medical school, PhD programs, Wall Street, or whatever passion they’re going to follow for the next 40 years of their lives. While they are incredibly passionate about their athletics, exams, papers, and internships are more important.

Keeping things in perspective and being realistic about college will minimize injuries due to lifestyle choices, as opposed to burying my head in the sand and treating the team as if it were a professional training group. I think this applies to all coaching situations as well—the balance of life on and off the track can’t be understated.

All coaching situations need to balance the athlete’s life on and off the track or field. Share on XIn terms of managing injuries and altering training, this situation again touches on communication. Luckily, we have amazing athletic trainers at Hopkins who are on the same page as to when to push things and when to hold back, and always keeping the larger picture in perspective. When an athlete is injured, we try to keep him or her active and fit by any means necessary without aggravating the injury. Most of the time, this contingency plan involves transferring sprint workouts to a stationary bike or pool and modifying the lifts to try to maintain as many of the benefits as possible.

For athletes who seem unable to tolerate the “ideal” training plan, I think it’s important to keep things in perspective. Taking a patient approach to training loads will alleviate a number of problems, as the gradual increases in loads over time accumulate to a well-developed training base. I’m actually going through this right now with one of my athletes—it’s a constant push-pull of having to corral the athlete with a history of injuries who is so eager to train.

This challenge is much better than the opposite scenario of an unmotivated athlete, but it is a struggle to drill the fact that consistently completing 80-90% of the written training is much preferable to alternating periods of 100% completion with periods of 0-20% completion. Keeping the end goal in mind and being patient when it comes to progressing towards that goal is, in my mind, the best way to handle alterations to training plans. The best ability is availability!

Tomorrow, we’ll feature the next installment of this Jumps Roundtable Edition #2 series: “Building a Technical Model.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF