I took a road less traveled to get to where I am today in my career: my degree is in an unrelated discipline, I never had an internship in the field, and I didn’t really find a mentor until 4-5 years into my career. The closest thing I had to an internship was back in 2008 when I decided to become a paying client at Mike Robertson’s gym, largely to observe how they trained, and also because I liked to read his online articles back then.

Long story short, it worked out. My unique journey has been almost a decade long, so I’m starting not to feel so new to the industry anymore. With that feeling comes reflection, and one thing I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is the importance of internships in our field. Although I personally never had one, I now own a facility and try to give our interns the type of experience I look back and wish I would have had.

Although I personally never had an internship, I now own a facility and try to give our interns the type of experience I look back and wish I would have had, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XEvery spring, decision-makers in our field tend to be inundated with applications, resumes, and emails that begin Dear Mr. [Insert Last Name] and make you feel way older than you actually are. Internships have a way of filling up quickly, so I wanted to put out this resource to help prospective coaches and interns in a way that can have a positive impact on their career.

Also, my hope is that the current hiring professionals on the lookout for interns or staff can benefit by exposure to the multiple perspectives of people who have been in their shoes. I reached out to a few professionals, both inside and outside the industry, to get their perspective on internships. Here are some great insights from people who have been interns, hired interns, and/or developed internship curriculums, providing actionable advice whether you’re hiring or applying for your next internship position.

Should Internships Be Mandatory?

We should first address the elephant in the room, so for the roundtable this was the ice-breaking question: “Should an internship be mandatory in our field?” The response from Joel Sanders, EXOS Performance Specialist, was firm and immediate:

“Yes.”

Elaborating, Sanders went on to say: “Yes [internships should be mandatory]. What other time in your life will you get four months where you can work your craft and just LEARN? I went to Georgia Southern, and we actually had the option to do another semester of courses or go do an internship. I thought that was the biggest no-brainer of my university career.”

Scott Charland, a former D1 S&C coach and currently the Manager of Human Performance of Parkview Health, agreed with Sanders, adding “I feel that an internship should absolutely be a requirement for the field. I actually think students should have to complete two internships (one junior year, one senior year) at different facilities. Nothing you learn in the classroom can take the place of hands-on experience. It also helps the student develop a network that will help them land a job upon graduation.”

Professionals in the trenches day in and day out highly value an internship as a pivotal learning experience—even taking the alternate route I took, I would have to agree with them. I benefited from there being no such requirement, but I definitely wish I would have gained that experience.

To play devil’s advocate, however, making internships mandatory would first require our field to make an Exercise Science degree (or related field) mandatory as well. That’s when the water gets murky. Coaches often complain about the current state of the industry and mention the low barrier of entry as a main reason for some of the flaws. The barrier isn’t just low, it doesn’t exist. A low barrier of entry would be something like a dental hygienist or X-ray technician. There are two-year programs that will fast-track you to those careers, and earn you a solid salary, and they are extremely important and respected jobs.

To play devil’s advocate, making internships mandatory would first require our field to make an Exercise Science degree (or related field) mandatory as well, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XTo be a trainer, the only requirement right now is to simply say “I am a trainer.” Make up some job title like Certified Functional Kinetic Mechanic, toss it on your Instagram bio, and you are officially in the industry. Now, of course, you wouldn’t have a shot at landing a high-level collegiate job, but you could work for yourself and nobody would blink an eye.

With that being said, a degree in a related field is becoming a more common requirement for many jobs. So, if universities push internships to be mandatory, that could potentially be killing two birds with one stone. Any graduate of the program will have the internship experience plus the degree, ideally satisfying the requirements of whatever job they apply for.

Coaches in strength and conditioning all have a responsibility to enhance this career so that it flourishes and becomes something that kids grow up wanting to pursue. This makes it an attractive college major, by which time internship and degree requirements may be in place to ensure a more prepared and educated young professional. At the end of the day, it’s not a method of weeding people out; it’s more of a method to make sure we prepare prospective coaches so that they make a great impact on the industry.

How Can Candidates Find the Right Internship?

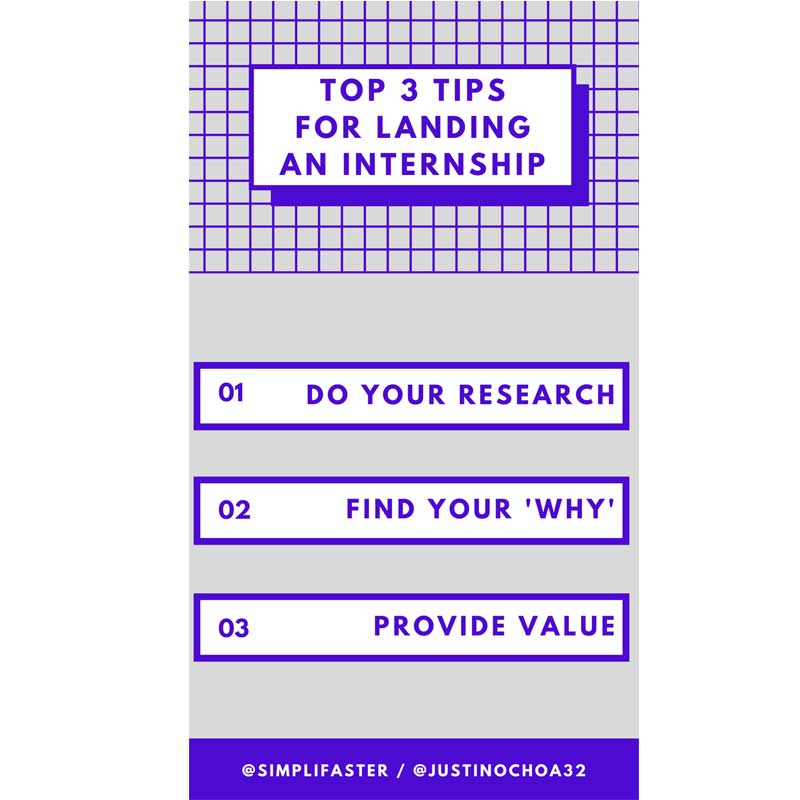

Having established a need for impactful internships, let’s develop ways to help prospects find those positions. There were three common denominators in the answers from every person I talked to on this subject.

- Do your research

- Establish your “why”

- Provide value

Let’s dive into those three things and how you can use them to find the best position for you.

Do Your Research

In todays’ world, information is accessible literally anywhere, anytime, and in a matter of seconds. The #1 thing you can do to make a great first impression on a job interview is to have an understanding of where you are, who you’re talking to, what they believe in, and how they get things done. There’s really no excuse not to.

For example, talking to Joel Sanders, I learned that he interned at EXOS before getting his full-time position with the organization. Prior to his internship, he read a book written by their founder and implemented its teachings into his own training to have a better understanding on the finer details of their training process.

That goes above and beyond, but there are even simpler ways you can do your research when applying for openings.

You can use the business or university website to familiarize yourself with the staff. You can review methodologies on social media outlets like Instagram, Twitter, or YouTube. You can listen to podcasts or read articles by the people at the business or university. All of this research will help you learn more about where you want to work and help you feel more comfortable during the interview process.

When choosing places to apply, I would suggest looking into places that are doing something that you could see yourself doing as a career, but that also make you uncomfortable at the same time. So, instead of your local university, maybe try one across the country. Instead of a private facility where you know the owners, try one where you know no one.

When choosing where to apply, I suggest looking at places doing something you could see yourself doing as a career, but that also makes you uncomfortable at the same time. Share on XGet out of your comfort zone as much as you can. Remember, this is a learning tool. Learning is greatly enhanced without the presence of comfort and complacency.

Start with ‘Why’

I totally just stole the title for Simon Sinek’s book with that subheader, but it’s that good. I would suggest every single human on the planet read the book. As a potential intern or as someone who is even just considering this field, it will help you find your core values and purpose while establishing career and life goals.

Establishing your “why” will help you develop a clear vision of how you want to approach your career, regardless of the field you choose. Your “why” may change and evolve over the years, but ultimately it all works together toward that same original vision.

As coaches, we get far too anchored to our niche elements. Scanning outside of our industry and learning from the perspectives of other professions is one of the best ways to enhance your coaching skill set. When I reached out to Taylor Tannebaum, an NBC Sports anchor and reporter, she added, “A great goal for an intern to have would be to try to learn enough about the profession to decide if this is truly a potential career path they want to choose.”

The beauty of internships is that they’re often a part of the educational model, so you could totally try something, hate it, and decide it doesn’t align with your “why.” Or, you could try something, love it, and confirm that you’re on the right path.

Provide Value

Offering his input on providing value, Old Dominion University’s Director of Sports Performance, Eric Potter, suggested, “Work as hard as possible, learn as much as you can, and be the ultimate assistant for the coaches and the athletes. Provide value to the department. Athletes are always the number one priority.”

As an intern, you’re there to learn, so your directors won’t expect you to immediately know every single thing. Some things you do have absolute control over are your work ethic, your attitude, and the way you treat others. If you can use those things to make yourself valuable, that will help you stand out and make an impact.

Providing value doesn’t have to be measured by the number of tiny tasks you complete or the minimum hours of sleep on which you can complete a 12-hour day. It can simply be measured by the impact of your efforts and the way you do things, rather than what you do. Try to find an internship that will allow you to use the unique skills that you possess, not just scrub toilets every week.

How Can Coaches Find the Right Interns?

As a coach, how do you go about finding, vetting, hiring, and ultimately teaching an intern? I asked a number of my colleagues the same question—What characteristics do you value most in potential interns?—and here is a “roundtable” of their insights and advice.

Missy Mitchell-McBeth (Head Strength & Conditioning Coach at Byron Nelson High School): “Initiative. At one time, my largest group of athletes was 14. I didn’t need much help, so I didn’t ask for it. My thought was, if I had to ask an intern to assist with the program, I probably had someone on my hands who would be more work for me than help. I’m not a very good hand holder, so I want people around me who can see a need and fill it. Several interns over the years took initiative and asked if they could be a part of the process. They were each an outstanding addition to my program.”

Scott Charland: “The characteristics I value most in potential interns are energy, enthusiasm, inquisitiveness, and consistency. When I was going through my hiring process to become an assistant strength and conditioning coach at Ohio State University, my boss, Anthony Glass, told me: I don’t care what you know, I’ll teach you everything you need to know. I just need to know if I can get along with you. This is how I feel about interns. I’m not looking for them to bring a bunch of new ideas or shift our entire training philosophy, I’ll teach them what I need them to know. I just need to be sure they can get along with myself and my staff.”

Taylor Tannebaum: “I value their willingness to help with anything—literally anything—not just the big, cool, exciting stuff. That’s critical. I also value their ability to pick things up quickly and figure things out. While I’m there to teach interns, I also don’t have time to be a babysitter. I value an intern who can pick up the task quickly, as it’s taught, and learn on the fly. A problem-solver, if you will.”

You want to find your next great intern? Look for a problem-solving attitude, leadership qualities, enthusiasm, sharpness, and most of all—Can you survive 12-15 hours a day with that person?

To find your next great intern, look for a problem-solving attitude, leadership qualities, enthusiasm, sharpness, and most of all—whether you can survive 12-15 hours a day with that person. Share on XHow do you find them? Just like attracting athletes to your school or business, your two best tools are:

- Word of mouth

- Marketing

Having a track record of interns enjoying their experience and moving on to earning full-time roles in-house or elsewhere does amazing things for your internship search. Not only will they tell their peers, but people in their network will already know about some of their moves based on social media and other outlets. Some of the best ways to ensure a great intern experience include:

Tannebaum: “I try to make their experience as similar to my day-to-day duties as possible. That way they truly know what it’s like. I know when I was an intern, I hated sitting there doing nothing. So, I give them even small tasks—like transcribing my interviews or logging big plays in a game that I may use in highlights later. I also let them be hands-on. I want them to shoot highlights with the camera; I have them do stand-ups and anchor a mock newscast. I also make sure to ask what it is they want out of the internship. If it’s something specific, I try to do more of that for them.”

Mitchell-McBeth: “[At TCU] we had a 12-week curriculum which included topics like program design, speed development, nutrition, etc. Additionally, we conducted ‘mock’ interviews during their final week where we, as staff, acted as a hiring panel interviewing potential candidates. I will tell you that prior to being hired on full-time at TCU, I was an intern there, and the mock interview is the most terrifying thing I’ve ever been through. Someone interviewing you in front of people you know is far more challenging than interviewing with strangers. I will say, having been through that experience, I now have ice water in my veins during real interviews!”

Charland: “There are several things my staff does to make sure our interns get a great experience. We spend A LOT of time going over exercises with our interns and putting them through these exercises. We have noticed that most interns coming to us have no practical experience with performing, let alone coaching, numerous weightlifting exercises, or sprinting, jumping, and agility drills and exercises. I tell every intern, this is a ‘doing’ internship, not an ‘observing’ internship. We also have weekly internship education meetings where we discuss the ‘why’ components of the program.”

Making the Internship Experience Work

Aside from being hands-on and realistic with your internship experience, I think it’s also extremely important to get personal and communicate well. Get to know your interns on a personal level, just like you would with an athlete. This will help you understand where they’re at, where they want to be, and how you can potentially help them get there. Treating every single staff member like they are the most important person on your staff lets them know you care about the person they are, not just the work they do.

From a marketing perspective, there’s the obvious platforms like social media and job boards. Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn seem to be the best three social platforms for listing jobs and getting good engagement. Other job boards such as the SimpliFaster job board or Indeed have great listings as well.

Aside from those, a very underrated form of marketing is a campus visit. You go to them. Set up visits to high schools or local colleges to get in front of their athletes and/or strength and conditioning classes. Plant those seeds. They may not apply now or next year, but maybe within the next 4-8 years you have a chance to mentor and work with that person in an internship setting because you went out and showed them what your world is all about.

Letting young adults know about our profession is how we can help continue to grow the field and set up the future generations to have a lot of the things we’re fighting for today, such as increased pay, improved benefits, larger staffs, and more time spent with loved ones.

Learn from Our Mistakes

To wrap up the roundtable, we can look at hard lessons learned from former interns who are now pros in their field. I’ll start with my take:

Make sure you try everything you can to get an internship, for all of the reasons stated throughout this article. I can’t stress enough how much I feel like not having an internship set me back early in my career. I definitely could have benefitted from the educational piece, but most of all, I never got the networking piece. You can self-teach anything you want if you learn from the right sources, but building your professional network early is something that can never be duplicated.

You can self-teach anything you want with the right sources, but building your professional network early is something that you can never duplicate, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XMitchell-McBeth: “I could have done a much better job building a relationship with the head strength coach. While it can be intimidating at times, remember that often this field is about who you know, and who is willing to help you find a position afterward. The strength coaches you are working around already have positions. They don’t need you. You should take the initiative as an intern to build this relationship and learn from them. It would have gone a long way for me to have simply asked to sit down with the head coach and talk about his program and why he does things a certain way.”

Charland: “As an intern, I could have shown more ownership. A big part of the intern’s job is to make the job of the full-time staff members easier. Our full-time staff members put a lot of time into training our interns. I’ve challenged our interns to ask my staff, when they first arrive for the day, what can I do to help you? I’m not sure I did this well enough when I was an intern. If an intern has to be constantly told what to do, that’s not a good thing.”

Tannebaum: “I could have been more assertive, asking to do more and not just waiting for tasks to come to me. I also could have taken it more seriously in the sense that it’s bigger than just college credit. It truly is an opportunity to learn, make connections, and get ahead for a future career. I remember in college sometimes I’d just be at my internship because I felt like I had to be. Taking it more seriously is something I could’ve been better at.”

I think the strength and conditioning field should look to maximizing the role of internships and how we use them to hire, connect, and educate, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XWith all of these things considered, I think the strength and conditioning field should look to maximizing the role of internships and how we use them to hire, connect, and educate. We’ve heard from professionals in the private and team settings, a hospital-based setting, and high school, college and pro settings, and even opinions from other fields.

If you’re someone looking into this space as a potential career, I hope you decide to jump in head first. If you’re looking to hire a candidate like that, hopefully this article gives you a nice broad stroke of refreshing info to use in your own hiring process. Like I said before, aside from performance goals, our current generation of coaches should put some emphasis on developing and building the industry. Internships seem like a no-brainer to accomplish this.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF