Designing a well-structured training program is vital for coaching track and field, and a big dilemma for coaches is how to accomplish event work for athletes who compete in more than one discipline. This is especially true for combined-event athletes, but also for sprinters/hurdlers, hurdler/high jumpers, and pole vault/long jumpers on both the high school and collegiate levels.

There are many options for programming and sequencing event work. I don’t believe any single methodology of compatibility is unequivocally better than another, but I do believe every coach needs to understand the overlap, differences, and interplay among the various approaches.

In this article, I will discuss different methodologies to sequence and pair event-specific work, and I’ll provide recommendations for best practices in the scholastic setting.

The importance of speed and power development cannot be stressed enough. Optimum development occurs when these two qualities are trained concurrently. Speed and power training improves neuromuscular integration by accelerating speed, strength, and coordination acquisition. It also improves muscle fiber recruitment, rate coding capabilities, and motor unit synchronization. When we organize training by high neural demand, we elicit an optimal and specific adaptation at the cellular level.

Due to the varying technical and physical demands of training for multiple events, however, programming can present numerous challenges. For example, the excessive density of high neural demand days will compromise the athlete’s central nervous system (CNS). An insufficient number of high-intensity days, though, will not induce any positive adaptations.

A too-heavy focus on event-specific technique work will stump long terms gains. But athletes need to be technically proficient (or at least competent) in an event to capitalize on their talent. During the mesocycle before a competition, it’s recommended that athletes practice at high intensity for consecutive days. Alternating high and low-intensity days, however, allows the nervous system to recover while work is still accomplished on the low-intensity, general days.

The interplay of these considerations determines the program’s success.

What should athletes do, for example, on high jump days? They could pair high jump work with acceleration development because the two have similar time programs. They could high jump on days they do max velocity work because both employ vertical firing patterns. They could also high jump before a special endurance workout, modeling a decathlete who races the 400m after high jumping.

Background

First, it’s important to understand each event’s requirements through a simple needs analysis. Speed and power capabilities are the dominant determinants of success for sprinters, hurdlers, and jumpers (400m runners come with a bit of a caveat, but they’re still clearly speed and power athletes). Training for combined-event athletes should also center on developing speed and power. For decathletes, nine out of ten of their events qualify as speed or power. For heptathletes, 6.5 out of their 7 events qualify.

For combined-event athletes, work capacity capabilities are more important than aerobic “fitness.” Share on XThere is a misguided notion that combined-event athletes need an aerobic base to be “fit” enough to withstand the rigors of competition. Work capacity capabilities are more important than an aerobic base because combined-event athletes must perform speed and power events at full intensity on two consecutive days. Developing these qualities with sprints, hurdles, jumps, and throws should be a top priority for coaches and athletes.

Pairing Philosophies

Pair by Time Programs

It’s common to pair event work by exercises that have similar time programs. A time program is a movement-specific innervation pattern. It’s determined by the neuromuscular impulse sequence of muscle activation as well as the duration and behavior of bioelectrical activity.

The ground contact time of a drop jump, for example, is a time program; it’s a quantitative expression of the fundamental movement program. Structurally similar movements are steered by the same time program, and time programs of varying lengths must be distinguished.

We can consider time programs for track and field movements in terms of ground contact times. Generally, shorter ground contact times lead to a more effective time program. Think of an athlete’s dorsiflexed ankle while at top speed, pretensioning before ground contact. By pairing similar time programs, we can send direct and concise messages to the CNS and a transfer among structurally similar movements becomes possible1.

Why pay attention to ground contact time (GCT) at all? The key to jumping far or running fast is generating a high amount of ground reaction force within the very short time period the foot is on the ground.

Everything comes back to power, which has both force and velocity components. Exercises such as squats are great for developing the force component of power, but very high-speed movements (i.e., GCT < 200ms) are needed to develop power’s velocity component.

Stratifying by GCT can also help frame the session’s goal. In jumps training, there is explosive strength and elastic strength, with a GCT threshold of about 200ms serving as the dividing line.2 Exercises such as box jumps, jump squats, and the Olympic lifts train the former while exercises such as hurdle hops, sprinting, and bounding train the latter.

The table below shows observed ground contact times in various events:

| Event | LJ | TJ | HJ | PV | Sprint (0-50m) | Sprint (0-100m) |

| Ground Contact Time (sec) | 0.12-0.15 | 0.10-0.20 | 0.13-0.21 | 0.12-0.20 | <0.15 | <0.10 |

From this, we can draw a few observations about which events naturally pair well. If working on acceleration, it makes sense to also work on high jump takeoffs since they have similar time programs.

If working on max velocity or short speed endurance, it makes sense to work on long jump takeoffs. While there aren’t many pole vault triple-jump combo athletes, coaches could plan bounding work with pole vault sessions.

Pair by Time of Force Application

Pairing event work according to the duration of power output will overlap with time programs. The idea is to work on events that have a similar force application. Think of this as a subgroup created by separating neuromuscular demands. For example, performing between-the-legs forward medicine ball throws helps potentiate for block starts.

Performing between-the-legs forward medicine ball throws helps potentiate for block starts. Share on XIn fact, we can build from a time programming pairing and prescribe the session’s workout based on the time of force application. If max velocity is the stressed quality of the day, then the weight room exercises of that day should complement the max velocity work performed on the track. Since max velocity running emphasizes high vertical ground forces and low GCTs, a natural weight room exercise following that session would be assisted jumps. We prescribe the day’s plan using similarities in the duration of force application.

Coaches can prescribe a day’s plan using exercises with similar duration of force application. Share on XWithin the track session, the athlete may perform 3-6 reps sprinting through a 20m zone at max velocity. Let’s call that 6-8 ground contacts per repetition. Executing an exercise like 4 sets of 8 reps of assisted jumps gives a similar time of force application. Linking these two exercises through similar power output durations reinforces the goals of the day.

This philosophy also makes the coach more conscious of total power output duration. This is critical because extended times of high power activities need to be carefully monitored to avoid overtraining and increasing the likelihood of injury.

To allow for the compensatory effects of high demand days and to minimize neural fatigue, low power output days should be included in an appropriate ratio.

Pair by Metabolic Demands

Pairing by metabolic demands resembles the time of force applications groupings, such as max velocity sprinting and assisted jumps. However, the differences between these two philosophies lead to important dividing lines when programming. For example, even though acceleration and max velocity work have different times of force application, they have essentially the same metabolic demands.

Organizing sessions according to energy system demands partitions workouts into one of three areas: activities that draw upon the alactic, glycolytic, or aerobic energy systems.

The alactic anaerobic (i.e., phosphate) system is the first energy system we use. It’s the muscles’ dominant energy source for roughly the first 10 seconds of high-intensity exertion. Next, the glycolytic (i.e., lactic) energy system takes over. This contributes most of the energy for as long as 90 seconds of activity. After a sustained bout of high-intensity exercise beyond 1.5-2 minutes, the aerobic system contributes the most energy. I’ve listed below example workouts grouped by metabolic demands:

- Alactic: 3x3x30m starts (3’/8’) + heavy cleans and squats

- Glycolytic: 5×45” runs at 85% (4’) + a general bodyweight strength circuit (3:1 work:rest)

- Aerobic: 8x200m at 65% (2’) + a general bodyweight strength circuit (1:1 work:rest)

Pair by Technical Similarities

Organizing event work by technical similarities can be broken down into two important subgroups; we can pair exercises by the orientation of firing patterns (horizontal vs. vertical) or by rhythm. Each subgroup offers an approach we can use to link events.

Longer sprints (between 50m and 300m) feature high vertical ground forces and emphasize the elasticity of the athlete’s musculature and pairs naturally with high jump work. Building from that, the high jump and the javelin also have similar approach rhythms (similar penultimate steps and body posture).

A logical sequence of events for a session would be javelin work, followed by high jump work, followed by a speed endurance workout. Even though the high jump is paired with two different events for two different reasons, the sequence of these three provides a natural practice flow based on technical similarities.

Pair Using Meet Modeling

While it’s impossible to truly simulate meet conditions in practice, sequencing event work according to the meet schedule can pay dividends in an athlete’s preparedness to compete. In addition to the combined events, this practice can be useful for specific meets.

Sequencing event work according to the meet schedule can pay dividends in performance. Share on XAt a championship meet, for example, are the 110m high hurdles before or after the 400m intermediate hurdles? This helps dictate practice set-up. Likewise, many invitational meets will start field events one to two hours before track events. If the athlete might long jump before running the 60m dash, it makes sense to work long jump approaches before technical acceleration work.

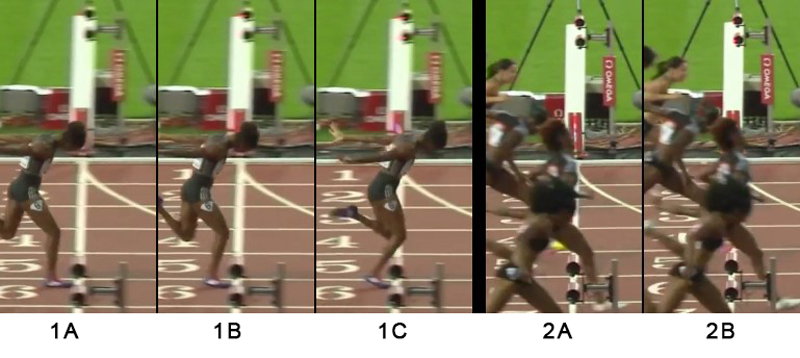

For the combined-event athlete, this is particularly important since every multi-meet will follow the same schedule. Heptathletes always hurdle in their first event and then high jump. Because we know this, it makes sense to practice hurdles followed by high jumps in the same practice session.

Also, since high jumps require a relatively long GCT for a jumping event, an athlete could practice hurdle starts (working on acceleration, which has a relatively long GCT compared to max velocity running or speed endurance work) and then work high jump takeoffs.

Decathletes always high jump first and then run the 400m. As discussed earlier, pairing high jump work with longer sprint work can be successful because the firing patterns are similar. In each of these cases, high jump is paired with another event according to the meet schedule.

This can create a logistical challenge when a team includes both males and females. Since decathletes high jump in their first event and heptathletes high jump in their second event, this can create an extremely long practice for the coach.

To combat this, the coach must pick and choose event pairings to fit logistics. In this example, if the coach is intent on having the decathletes simulate running a 400m after high jumping, the coach can change the heptathletes’ practice so they also high jump first followed by speed endurance. This specific example works out well because heptathletes will high jump and run a 200m dash on the same day. The coach will plan a meet-specific day for the heptathletes for another time.

When planning based on meet preparation, coaches should realize that a combined-event athlete specifically needs to practice execution on back-to-back high neural days. Although I usually like following high-intensity CNS days with low-intensity general days, it’s important to have subsequent high-intensity days to prepare athletes for their two-day competitions.

During the general prep and specific prep phases, I like to alternate high and low days. This takes advantage of an alternating system’s benefits to build the best athlete possible, in the purest sense of the word.

Next, it’s vital to include back-to-back high-intensity days in the pre-competition and competition phases to help transition the athlete into the best combined-event athlete possible.

For decathletes, this includes working long jump and max velocity on the first day and then hurdles and vault work on the second day. For heptathletes, this includes working hurdles and high jump together on one day, followed by javelin and aerobic power work the next day.

For all combined-event athletes, it’s important they practice a technical event (hurdles or vault for men, long jump or javelin for women) the day after finishing a practice with speed endurance work. The more acclimated they are to executing events with high technical, speed, and power demands under neural fatigue from the previous day, the better they will perform in the meet.

Additional Thoughts, Guidelines, and Recommendations

- During general and specific prep periods, begin sessions with technical work when the athlete is not fatigued. This is especially important for developing athletes. Regarding the microcycle, do more technical work at the beginning of the week when the athlete is fresher.

- Use lower intensity days to emphasize a lot of technical work.

- This provides the added benefit of increased motor unit recruitment and targets any residual muscle fibers not fully activated from the prior day’s session.

- As high-intensity days become more intense, the lower intensity days require a shift in focus from building work capacity to recovery.

- Complementary training can be used. The athlete, for example, would complete a hard long jump day on Monday followed by reinforcement through easy long jump drills on Tuesday, or javelin throws one day followed by javelin-specific medicine ball throws the next day.

- When using a high-low scheme, do accelerations on Monday (Day 1 of the microcycle) to potentiate for max velocity work on Wednesday (Day 3 of the microcycle).

- You don’t need to address every event every week, especially in the scholastic environment. Yes, in a professional environment, it’s common for decathletes to throw every day, but it’s not practical for students dealing with 15-18 credits and other extracurricular activities.

- Keep in mind that each athlete has his or her own strengths and weaknesses that need to be addressed at varying levels. Many younger college decathletes may need to spend more time pole vaulting since it’s a difficult event to practice in high school.

- You can use long jump approach work either as acceleration or max velocity fly work, depending on the length and rhythm of the athlete’s approach.

- It’s important to use all of the philosophies I’ve mentioned to develop a multilateral approach to training.

- Pair weight room exercises and plyometrics accordingly, not just event work. For example:

- Deep box squats and broad jumps on acceleration days (overcoming inertia).

- Clean-grip snatches and explosive hurdle hops on max velocity days (explosive lift with a large amplitude).

- Don’t forget the importance of general days.

Sample Programs

Here are two sample programs that employ these ideas. First is a brief, two-microcycle layout for a decathlete during his specific prep phase using a reverse step loading pattern:

| Monday (Acceleration theme) | Tuesday (General) | Wednesday (maxV) | Thursday (General) | Friday (Tech) | Saturday (Int. Tempo/Speed End) | Sunday | |

| Microcycle 1 | Hurdle starts (5x2H), High jump work (short approach jumps) | All on grass field: Long jump takeoff work over mini-hurdles, Extensive tempo (2,000m), Med ball circuit | 4x Sprint-Float-Sprint 90m (30-30-30) | Shot put technique work followed by a general strength bodyweight circuit | Hurdle technique work (1-step and 3-step drills, 80% drill (4x6H)) | Short approach vaults, followed by javelin work, and then speed endurance (4x120m @ 98%, 8-10′) | REST |

| Weight room: Power cleans (4×3 @ 85%), Heavy box squats, Incline bench press (4×3 @ 85%) | Weight room: Assisted jumps (4×8), Clean-grip snatches (4×3, light), Dynamic step-ups (3x6ea) | Weight room: Special exercises (1-leg cleans, Step-ups into a push press, etc.) | |||||

| Microcycle 2 | Hurdle starts (4x3H), Long jump (approaches with and without takeoff) | High jump work (curve running), javelin technique work, combination of extensive tempo (1600m) and bodyweight exercises | Pole vault full approaches, 4x flying 30s (30+30) | Discus technique work followed by an aerobic capacity workout in the pool | Hurdle technique work (1-step and 3-step drills), Shot put work (~15 total throws) | Javelin work, Speed endurance: 3x120m @ 98% (10′) | REST |

| Weight room: Power cleans (4×3 @ 80%), Heavy box squats, Incline bench press (4×3 @ 80%) | Weight room: Assisted jumps (3×8), Clean-grip snatches (3×3, light), Dynamic step-ups (3x6ea) | Weight room: Special exercises (1-leg cleans, Step-ups into a push press, etc.) |

As you can see, the event work is paired at various points according to time program, power output, metabolic demands, rhythm, and meet specificity.

In Week One, the athlete will high jump fresh on Day 1 and then work long jump takeoffs while sore on Day 2. In Week Two, he will long jump fresh on Day 1 and then work high jump while sore on Day 2. He gets practice pole vaulting while fatigued to simulate meet conditions (Week 1, Day 6). Day 3 of both weeks is a very high-intensity max velocity day on the track paired with assisted jumps and clean-grip snatches in the weight room. Each of these days is followed by a very easy general day to allow the athlete to recover.

Next, I’ve included a sample microcycle for a high school athlete in her pre-competition phase. She trains only four sessions per week and competes in the hurdles and long jump. She has very limited weightlifting experience, and in this case, the coach is using a forward step loading pattern:

| Monday (Acceleration theme) | Tuesday (General) | Wednesday | Thursday (maxV) | Friday | Saturday (Speed End) | Sunday | |

| Microcycle 1 | -Hurdle starts (5x2H, 4’) -LJ takeoff drills and short approach jumps -Bounding |

All on grass field: Extensive tempo (1,200m), Med ball or General strength circuit |

REST | -4 Full LJ approaches -LJ takeoff and/or landing drills -4x Flying 10’s |

REST | -Speed bounding -Speed end. HH workout/race modeling: 3xfull Hurdle race (H5-H7 pulled out; 10’) |

REST |

| Weight Training: -DB Front squat+push press combo (3×5) -DB Bench press (3×5) -DB RDL (3×6) |

Weight Training: -DB Jump squats (4×4) -DB Push press (4×4) -DB Bench press (4×4) |

||||||

| Microcycle 2 | -6 full approach LJ run-throughs -Hurdle starts (5x3H) |

On grass field: LJ takeoff work, Extensive tempo (1,600m), Med ball circuit |

REST | -4x6H (80% drill) -3×20-20-20 (Sprint-Float-Sprint, 5’) |

REST | -6x Short approach jumps -Speed endurance: 2x2x80m @ 98% (8’/12’) |

REST |

| Weight Training: -DB Front squat+push press combo (4×4) -DB Bench press (4×4) -DB RDL (4×6) |

Weight Training: -DB Jump squats (5×4) -DB Push press (5×4) -DB Bench press (5×4) |

I hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I did writing it and please leave any comments or questions you have below. Special thanks to Nick Newman for his immense support and guidance throughout the past few months and for the years to come.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

- Elliott, Bruce, and J. Mester, eds. Training in Sport: Applying Sport Science. Chichester: J. Wiley & Sons, 1998.

- Smith, Joel. “Why is Ground Contact Time Important in Plyometrics.” verticaljumping.com. 2014. Accessed July 12, 2016.

- Newman, Nick, and Dr. Phil Graham-Smith. “Beyond the Force Velocity Curve with Assisted Jumps Training.” SimpliFaster (blog). July 13, 2016. Accessed July 31, 2016.

- Lefever, Dan. “Considerations in Coaching the Combined Events.” U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association. Dec 19, 2012. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- Broadbent, Eric. “Multi-Events Training Part 1.” Speed Endurance. Jan 6, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- Broadbent, Eric. “Multi-Events Training Part 2.” Speed Endurance. Jan 14, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- Broadbent, Eric. “Multi-Events Training Part 3.” Speed Endurance. Jan 21, 2014. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- Rovelto, Cliff. “Three C’s of Combined Event Training.” USA Track & Field. July 1, 2016.

- “Report from the Combined-Events Committees (Decathalon & Heptathalon).” USTFCCA. USA Track & Field. Dec 13, 2006. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Hierholzer, Kyle W. “Coaching the Multi-event Athlete.” Colorado High School Coaches Association. Accessed July 12, 2016.

- Sunquist, Eli. “Combined Events Training for the High School Athlete.” Elite Track and Field Training. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Schexnayder, Boo. “Periodization Models for Speed Development Support.” National Strength and Conditioning Association. July 6, 2016. Accessed July 16, 2016.

- Burnett, Angus. “The Biomechanics of Jumping.” ELITETRACK Sport Training & Conditioning. Accessed July 1, 2016.

- Veney, Tony. “Sprints: Training the Energy Systems.” Coaches Education. Accessed July 24, 2016.