The reality in the world of high performance strength & conditioning is that athletes will face interruptions in their training at some point or another. In some cases, injuries occur. Some are very minor and training can resume as planned with some modifications. Other times, medical interventions are necessary followed by complete rest of varied durations.

It is also worth mentioning that athletes also voice their worries over losing their physiological adaptations when coaches employ periods of active rest or tapers. For both the strength & conditioning coach and the athlete, it is important to have a general understanding of what happens to an athlete’s ‘physiology’ during a short-term period of detraining. It is important to understand the potential effects and understand the mechanisms of any changes in physiological capacity.

This brief article categorizes ‘Detraining’ as part of the Principle of Reversibility. This principle is broadly defined by stopping or markedly reducing physical training leading to an induction and a partial or complete reversal of adaptations earned from training. As mentioned previously, interruptions in training could include illness, injury, active rest cycles or other reasons.

Detraining is defined as: “the partial or complete loss of training induced anatomical, physiological or performance adaptations as a consequence of training reduction or cessation” (80). Training cessation implies a “temporary discontinuation or complete abandonment of systematic programme of physical conditioning” (80).

A taper, on the other hand is “A progressive non-linear reduction of the training load during a variable period of time, in an attempt to reduce the physiological and psychological stress of daily training and to optimize (sports) performance” (80).

Timelines Defined

Losses of training-induced adaptations differ depending on the duration of the period of insufficient training stimulus (80). A 4–week block (short-term) is the reference point for this article.

Populations Examined

It is also critical to mention, “Some detraining ‘effects’ are not the same when we compare the elite athlete with several years of training history to the previously sedentary, recently trained person who engages in activity for health-related purposes versus performance purposes.”(Bott and Mujaika, 2016).

This article discusses the process of detraining, during a 4-week period (short-term), as it pertains to each system of the body. Within each system, the article attempts to compare the “endurance-trained athlete” to the “recently trained person” – two very different populations.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the endurance-trained athlete is defined not exclusively as an endurance athlete (marathoner, road cyclist etc), but rather an athlete who possesses a relatively high aerobic capacity. However, in the studies reviewed for this article, exact capacity values were not clearly defined.

Systems of the Body

1. The Cardiorespiratory System

Maximal Oxygen Uptake (81)

- Shown to decline with short term (<4 weeks) training cessation in highly trained individuals with large aerobic power scores.

- The % loss is somewhere between 4 and 14%.

- Essentially, some studies are showing the higher trained, the bigger the decline.

- Conversely, that of the recently trained has been shown to decline to a much lesser extent (3-6%).

Blood Volume (81)

- Total blood volume as well as plasma volume have been shown to decline by 5-12% in endurance-trained athletes. This essentially limits End-Diastolic Volume (the phase where the heart fills up with blood – large amounts are good) and consequently the End-systolic volume (the amount of blood left in the heart after it contracts to push the blood out – small amounts are good)

- Plasma volume can decline in the first 2 days of inactivity so this has implications for tapering.

- In recently trained individuals there is also reduce blood volume (red cell mass and plasma) so this effect is not limited to those more trained.

Heart Rate (81)

- As a result of the decrease in plasma volume, there is a relatively acute increase at submaximal and maximal workloads (5-10%). This is important if a coach is using heart rate as a means of monitoring intensity.

- However, this effect is reversed when plasma volume is expanded.

- Stabilizes after 2-3 weeks without training

- Resting heart rate unchanged in endurance-trained individuals

- In recently trained individuals: Resting Heart Rate and Maximum Heart Rate can revert quickly to pre-exercise levels but Submaximum HR is not affected.

Stroke Volume (81)

- Since blood and plasma volume decreases, stroke volume follows suit and is reduced.

- Reduction in maximal aerobic capacity shown by endurance-trained athletes.

- After 12 – 21 days of cessation, a reduction of 10-17% has been reported along with a corresponding 12% reduction in Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension.

- No observations have been summarized on recently trained persons.

Cardiac Output (81)

- The increased Heart Rate values resulting from detraining does not counterbalance the decrease in stroke volume in endurance-trained athletes.

- Thus, cardiac output is reduced substantially (8%) with 21 days without training in endurance-trained athletes.

Cardiac Dimensions and Blood Pressure (81)

- Some researchers observed no change in such a short time.

- Some observed a 25% decrease in Left Ventricular wall thickness and a 19.5% reduction in LV mass after only 3 weeks in endurance-trained athletes.

- A reduction in LV mass and a higher total peripheral resistance could lead to increases in mean arterial pressure during exercise when an individual becomes detrained.

- In recently trained individuals who trained for 8 weeks lost all positive effects on systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). They were completely reversed.

Ventilatory Function (82)

- A decline in maximum ventilatory volume is observed in highly trained individuals

- This often declines parallel to VO2 max (maximal oxygen consumption)

- There is no commentary on recently trained individuals on this characteristic

Endurance Performance (82)

- A loss in the characteristics of cardiorespiratory fitness lead to performance impairments in endurance-trained individuals

- Slower times to complete distances

- Shorter exercise times to exhaustion are performance indicators

- In recently trained individuals (6-12 weeks of training), 2 weeks of training cessation did not sufficiently reduce time to exhaustion.

2. The Metabolic System

Substrate Availability and Utilization (82)

- In endurance-trained athletes, the increase in the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) at both submaximal and maximal exercise intensities results in a higher reliance on carbohydrate metabolism

- Insulin sensitivity also decreases which is linked to decreased lipid mobilization during exercise

- There is an observable reduction in GLUT-4 transporter protein content – Skeletal muscle stores glucose as glycogen and oxidizes it to produce energy. The main glucose transporter protein that mediates this uptake is GLUT4, which plays a key role in regulating whole body glucose homeostasis.

- Also, a decrease in muscle protein lipoprotein lipase activity. Lipoprotein lipase breaks down fat in the form of triglycerides, which are carried from various organs to the blood by molecules called lipoproteins. This leads to a decrease in HDL cholesterol (the good guys) and increase in LDL cholesterol (the bad guys)

- With respect to individuals recently trained, all values of insulin, RER and GLUT-4 go back to initial levels (pre-training levels).

Blood Lactate Kinetics (82)

- Endurance-trained athletes have been shown to respond to a standardized submaximal swim with higher blood lactate levels after only a few days of training cessation.

- This is accompanied by a lowered Bicarbonate level

- LT occurs at a lower % of VO2 max

- *Muscle’s oxidative capacity may fall as much as 50% in one week.

- In recently-trained individuals, lactate levels did not change with cessation of exercise, even after 6 weeks of training. It is presumable that it takes several months, if not years to significantly improve lactate threshold in previously untrained individuals.

Muscle Glycogen Stores (83)

- Negatively affected by training cessation in as little as one week due to rapid decline in glucose to glycogen conversion and rapid decrease in glycogen synthase activity.

- No specifics on particular populations.

3. The Muscular System

Muscle Capillarization (83)

- Declines or doesn’t change in such a short amount of time

- In highly trained athletes, it still remains 50% higher versus sedentary controls

- With recently trained individuals, levels still remain higher than pre-training values after 4 weeks of inactivity

- This indicates the robustness of this adaptation.

Arterial-Venous Oxygen Difference (83)

- Data available is sparse

- Indicates no change in 21 days, lending support that the decline in VO2 max is likely due to central factors: decreased stroke volume.

Myoglobin Level (83)

- In both trained and recently trained individuals, cessation did not affect myoglobin levels in such a short period of detraining.

Enzymatic Activities (84)

- Citrate synthase (the enzyme in the first reaction of the Kreb’s cycle in aerobic metabolism) activity decreases between 25 and 45 % with short term training cessation in trained athletes.

- Decreased muscle oxidative capacity is reflected by significant (12-27%) reductions in enzymes that facilitate ATP production in aerobic pathways (beta-hydroxyacyl CoA-dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase and succinate dehydrogenase)

- Lipoprotein lipase activity in muscle tissue decreases, favoring storage of adipose tissue

- Glycolytic enzymes decreased only slightly with the exception of glycogen synthase which decreased 42% after only 5 days

- All of the above information pertains to trained athletes

- For those recently trained, mitochondrial enzyme activities have been shown to decline to pre-training levels.

Muscle Fiber Characteristics (84)

- Human skeletal muscle is highly plastic tissue and improvements in measurement techniques have allowed the human muscle to be studied in a more functional context (Harridge, 2007).

- It is the properties of muscle which are altered by changes in physical activity (Harridge, 2007).

- Harridge’s review discusses, specifically, the contractile machinery of the muscle and how it is sensitive to mechanical loading. Should those loads be removed for a period of time due to injury, specific fiber types will atrophy.

- Disuse, due to detraining, has the effect of causing slow to fast transformation of muscle fiber type expression. This may lead coaches to blindly conclude this as being an ideal adaptation for speed and power.

- What one must keep in mind is the atrophy that comes with disuse negates any benefits of slow-to-fast transition in terms of fiber function.

- Mean fiber cross-sectional area in Type 2 fibers, can decrease in 2 weeks

- Percentage distribution of fiber types were unaltered in recently trained individuals during 4 weeks of inactivity.

*The mechanisms of fiber transitions are beyond the scope of this article.

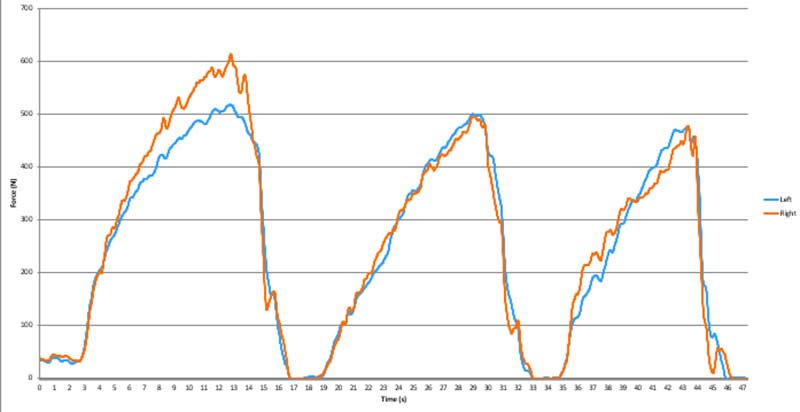

Strength Performance (84)

- Strength-trained athletes showed slight, but non-significant reductions in Bench Press, Squat and Vertica Jump after 2 weeks without training

- However, it is important to note that swimmers were not able to demonstrate same force to the water (power) after 4 weeks of inactivity.

- In recently trained individuals, after 4 weeks of inactivity, strength was still higher than pre-training values.

4. The Endocrine System (84)

- Decline in insulin sensitivity

- Unaltered catecholamine levels at rest and after submaximal exercise

- Glucagon, cortisol and Growth Hormone did not change with 5 days of inactivity in endurance athletes

- Strength trained athletes show positive anabolic hormone changes after 14 days of inactivity, with:

- Increased GH levels

- Increased Testosterone levels and T:C Ratio

- Decreased Cortisol levels

Short-term Detraining Re-Cap

- “The partial or complete loss of a training-induced adaptation in response to an insufficient training stimulus” (85).

- Short term is defined as less than 4 weeks of inactivity.

- Losses depend on the training status of the subject.

Conclusions and Implications for Tapering

- Rapid decline in VO2 max with highly trained athletes.

- Much less in recently trained individuals.

- Due to immediate reduction in blood volumes and reduction in stroke volume

- Thus, endurance performance declines rapidly in trained athletes.

- Higher reliance of CHO as a fuel source

- Decreased muscle lipoprotein lipase activity

- Lactate threshold lower at % of VO2 max

- Muscle glycogen levels rapidly decline

- Significant reduction in oxidative enzyme activities and thus reduced ATP production

- Non-systematic changes in Glycolytic enzyme activities

- Muscle fiber distribution remains unchanged

- Fiber cross sectional area declines (atrophy) in strength and sprint trained athletes.

- Strength can be maintained for up to 4 weeks of inactivity.

- However, sport-specific power of athletes may suffer declines

- Anabolic hormones may increase in strength-trained athletes

Works Cited

- Harridge, Stephen D. R. (2007). Plasticity of human skeletal muscle: gene expression to in vivo function. Experimental Physiology. 92.5 783-797.

- Mujika, I and Padilla, S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of training-induced Physiological and Performance Adaptations. Part 1. Short Term Insufficient Training Stimulus. Sports Medicine. 30 (2). 79-87.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF