The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is one of the most important systems in the human body for health and well being. Its processes have vast effects on your internal systems and can affect general health both short term and long term. On top of general health, the ANS is linked more closely with performance than I previously imagined. Let’s look at the ANS and how it influences performance both chronically and acutely. If you’re anything like me, you’ve completely underestimated how important it is and how to influence it.

What is the Autonomic Nervous System Exactly?

The ANS is not to be confused with the Central Nervous System (CNS). The CNS is responsible for all movement and function from an active/conscious standpoint. The CNS activates when you want to accomplish certain tasks and have a certain amount of conscious control. The CNS is responsible for activating motor units and creating muscle action.

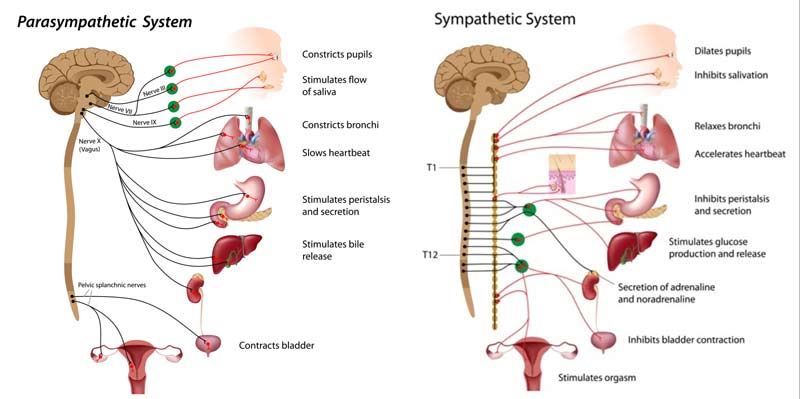

The ANS, on the other hand, is responsible for autonomic processes in the human body that require no conscious control–things like breathing, heartbeat, and digestion (as well as countless others). You don’t have to tell yourself to do these things, they happen whether you’re thinking about them or not. Of course with breathing, you can choose to alter how you breathe, but regardless, your body will get oxygen without your thought. We’ll get more into breathing later on. The ANS also has two branches: Sympathetic Nervous System and Parasympathetic Nervous System.

The sympathetic state is our stress response, which most people refer to as “fight or flight.” The stress response is meant to prioritize short-term survival by making energy more readily available, increasing blood pressure, heart rate, adrenaline, etc.

The parasympathetic state is our relaxed state, which most people refer to as “rest and digest.” This state is intent on long-term survival and prioritizes recovery, digestion, and relaxation.

As a coach, I used to understand very little about how the ANS affected my athletes, so there may be other coaches out there who would benefit from a greater understanding. Let’s get into what these states mean from an acute and chronic perspective and the myriad ways we can influence them.

Chronic Stress and the Autonomic System

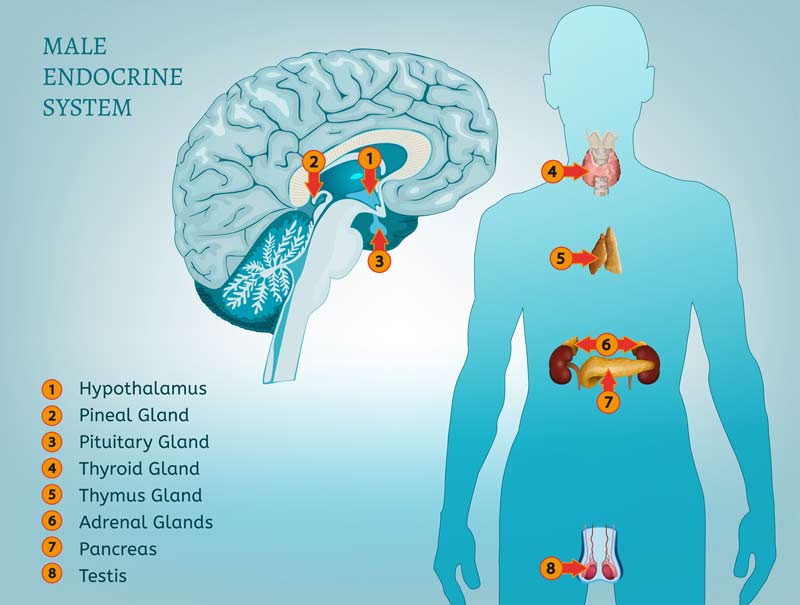

What’s remarkable about the ANS is that its activation has long-standing effects on our overall health and well being. When you’re stressed, the sympathetic system kicks on and creates a cascade of stress responses like raised blood pressure and heart rate, reduced saliva, increased adrenaline, and a slew of other processes. Your body senses something difficult or stressful and piles on the effects to help you combat them. From an evolutionary perspective, this would mean the risk of danger or death. It’s what makes the sympathetic system interesting.

In How Children Succeed by Paul Tough, the author uncovers a correlation between many chronic diseases and a person’s history of stressful events. Someone who has activated their sympathetic system for a long time develops chronic diseases from the repeated stress response during that time. What’s most interesting is how the body responds to varying levels of stress and danger in virtually the same way.

In his book, Paul borrows from Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert Sapolsky and likens the response to a fire department. The fire department sends out trucks for any call, not just deadly fires. They sound the alarm and mobilize the trucks for a dumpster fire because that’s their response, they don’t choose to send one firefighter on a bicycle in that scenario, they send the whole fleet.

The body does something similar; there’s very little context for the stress response. If something causes stress, physically or mentally, the body always responds the same way. Spending a lifetime in the sympathetic state is a dangerous place to be. It will hinder recovery and lead to a shorter lifespan. And yet we wouldn’t want to turn off the mechanism. The stress response influences the body for short-term performance and survival. So how do we balance the body?

Even though the stress response is autonomic, we still influence its action. As athletes, we’re are open to the same life stressors as anyone else plus the sympathetic reaction to intense training and competition. If you’ve never realized it, intense training is a major stress to the body.

We should be open to activating the sympathetic nervous system acutely to increase performance for competition. We can do this many ways, including listening to intense music, doing a competitive warm up, or even mental imagery. In this study, mental imagery activated the sympathetic state in a way similar to doing the activity. Coaches should keep this in mind when they need their athletes activated because some of them may have a hard time getting up for competition.

It’s a difficult task–how do we influence the body’s ANS to aid us both in short-term performance and long-term health.

Athletes need to stimulate the #parasympathetic response to drive recovery, says @kennedyk24. Share on XThe more information I collect on the ANS, the more I realize how important it is for athletes to stimulate the parasympathetic response and drive recovery. This can occur after exercise–or during if it’s a longer activity. The parasympathetic system prioritizes long-term health and shifts focus to recovery and relaxation. Things that get turned off to focus on survival (sympathetic) reactivate when we focus on relaxation (parasympathetic). If you’re familiar with Wim Hof, much of what he does involves tapping into and influencing the ANS for amazing feats.

So what does this mean for our athletes in the short term and the long term?

Chronic Considerations of Parasympathetic Activation

Although it’s possible to become overly parasympathetic (ask Dr. Mike Nelson), I don’t think our readers and clients will have this issue. For the most part, we lack chronic activation of the parasympathetic system. As athletes, we constantly put our bodies into a stressful state. For this reason, it’s more important to educate our athletes about the mechanisms necessary for parasympathetic activation. For those who need tools to activate the parasympathetic system, I offer some strategies toward the end of this article.

Even though it is autonomic, there are many ways we can influence the parasympathetic state. Too often, I hear people discussing stress in a general sense, and I’m frustrated by how misleading the conversations are. Most people believe stress and relaxation are out of their control, or the things they believe to be stress relievers actually are not.

Yes, stress happens, but if you want to relax, then you should actively try to put your body in a relaxed state. Research has shown that there are several ways to influence the ANS. As an example, this study shows how stretching after exercise can drive parasympathetic activity. Without stretching, sympathetic activity would be elevated at this point.

These are the small interventions we can pass on to our athletes without altering anything in our training program. In a sense, the ANS is very much like the CNS: for performance, we want to become efficient at activating the system. However, we’d be hardpressed to find a coach who wants their athlete to continue taxing the CNS outside of training and competition.

Likewise, driving a sympathetic response in training and competition is beneficial, but an extended sympathetic state could have negative effects over the long term. A light switch is a perfect analogy. When we need light, we want it to be efficient and effective (acute), but it’s wasteful to leave it on all the time (chronic). Learning how to turn it on (sympathetic) and off (parasympathetic) could play a significant role in athletic development.

As a coach, I look for ways to reduce the amount of stress/load/activity on my athletes away from training so that, when we choose to activate/overload them, we get the performance we want. If you haven’t yet considered the “state” your athletes are in away from training, you may want to begin investigating.

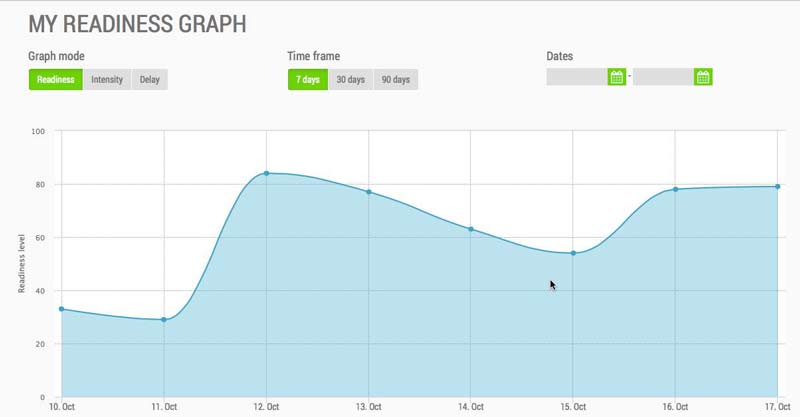

From a long-term perspective, this probably means monitoring HRV and using daily readiness questionnaires to see trends in their answers. These tell us how they are responding to their training and lifestyle. The information is especially valuable both for long-term health and performance results. How does their body respond to this day, week, and block of training? How do they respond to various types of training? These are very important factors to be sure and have been discussed in other HRV articles; consider reading more on that topic.

What’s been interesting to me lately is how we can influence or use the autonomic state for performance and, specifically, acute responses. What sort of interventions can we use to create a desirable response in our athletes?

Acute ANS Repsonses

Will the current state of my athlete dictate their performance in any way?

Is there anything I can do to influence their body through their warm up or competition prep?

It would be very easy to look past these questions and only consider the biomechanical and physiological components of preparing the athlete for competition–like priming the CNS and prepping movement patterns or tissues. At the least, it’s worthwhile to ask yourself if your athlete is ready or “activated.”

Some of the elite coaches I’ve talked to have a definite grasp of the interventions affecting the autonomic state, although sometimes they don’t refer to it this way.

The #sympathetic state allows for increases in short-term performance, says @kennedyk24. Share on XIf we look a little more closely at competition, we see other factors at play that can affect outcomes. The sympathetic state allows for increases in short-term performance. The purpose of the fight or flight response is to increase our abilities in a situation where our life might be at risk so we can succeed against our foe. This means that our body will do such things as:

- increase our sense perception

- mobilize energy for fast consumption

- increase blood pressure and heart rate to deliver energy

- inhibit pain response

With an acute threat, the body prioritizes necessary acute responses over long-term processes (increased blood flow for delivery of nutrients and oxygen over digestion). It’s safe to say that elite competition occurs in a sympathetic state.

Elite competition occurs in a sympathetic state, though athletes transition at different rates. Share on XWhile looking for more answers about how the ANS affects performance, I contacted Steve Fudge, Sprints Coach with British Athletics, to learn about his experiences. I had heard that Steve collected saliva samples from his athletes and gathered data. He observed that his athletes had differences in how quickly and efficiently they transitioned in and out of the sympathetic state. This fact should push coaches to try and identify their athletes’ transition rates.

In an ideal world, we’d flash into the sympathetic state to use its performance-enhancing processes and then go back to parasympathetic quickly to allow for recovery and lessen the damage of the long-term stress response (zebras and ulcers). Especially considering that some athletes take up to 24 hours to recover completely from a workout or practice, as shown in this study on HRV in sport.

The challenge is that athletes might need to be classified and treated differently in this regard. Steve used the terms warrior and worrier (which he may have borrowed from Henk Kraijenhoff), and it gave me a bit of an Aha! Moment, if I’m honest. I’ve observed this with athletes, and I know other coaches who have dealt with this, but in hindsight.

The warrior is someone who doesn’t turn on the sympathetic state easily. This athlete is pretty chilled out most of the time. On the flipside, the worrier is often sympathetic and is generally stressed out about many things. Plugging your athlete into one of these categories can really help you customize their competition preparation.

The warrior needs to be activated. This athlete needs a more rigorous and competitive warm up to enter the sympathetic state and achieve the stress response we want. The worrier may become too agitated and active. Remember, we only want to activate for competition or the repeated stress response could be detrimental to health and performance. This athlete should probably be controlled more throughout their pre-competition routines. One group of athletes needs a push, and one needs a pull.

- Did your athlete burnout too soon?

- Did they fail to rise up and hit training PRs/projections?

These are the potential outcomes from never looking at, or considering, your athletes’ hormonal status.

Luckily we have coaches like Steve, who has the budget and foresight to do hormonal testing and provide us with data; I’d never be able to do that. What I can do, though, is be an observant coach through training and competition. When looking at performance outcomes, in both training and competition, it’s important to note an athlete’s external factors:

- How do they train when they’re going through stressful times?

- How easily do they get activated in training?

- Do they overachieve in competition or underachieve?

If you’ve never considered these questions, it’s time you started to think about them. Luckily, providing your athlete with tools to aid their recovery is one of the easiest things you can do.

Coaching Methods to Maniplulate the ANS

Instead of simply sharing my observations, I think it’s important to have actionable items to impact an athlete’s sympathetic state. Here are some common ways to influence and activate the ANS. These are a list of popular parasympathetic interventions to help your athletes relax and recover.

Deep Breathing

One of the simplest and most common solutions is deep diaphragmatic breathing. Slow deep breaths into your diaphragm signals to your body that you’re in a relatively safe space and helps kick on the parasympathetic system. Deep breathing also gets the diaphragm working. Consider implementing deep breathing a few times a day to calm nerves and aid recovery. If you fit one in early in the day, your diaphragm should be humming along nicely. I mention deep breathing first because it’s part of many of the other parasympathetic interventions.

Meditation

Meditation has slowly become more common with both athletes and non-athletes. Practicing meditation no longer holds the stigma of being a hippie; now it’s associated with mindfulness and self-reflection. Spending some quiet time alone trying to be mindful really can help relax the body. Deep diaphragmatic breathing is often used during this practice, so the parasympathetic response will be there. If you’re into flow, this could be a great way to get into it.

Stretching

Although some people are in the habit of stretching post workout, there are still may who gloss over it. This study suggests that static stretching after workouts can induce a parasympathetic response. If you take your time while stretching, you can also tie in meditation and deep breathing. I’ll include Yoga in this category, although it’s a unique blend of stretching, breathing, and meditation.

Float Tanks

Float tanks have been gaining popularity lately. The concept is simple–a tank is filled with close to 1000lb of Epsom salts and closed off from sight and sound. The salt and water temperature make the body feel weightless and also eliminate feeling on the skin. The sensory deprivation helps keep the nervous system from being active. The only way to stop yourself from processing information is to stop the information from coming in.

When I asked Steve about float tanks, he said this was possibly the most effective parasympathetic intervention. One of the many reasons is probably because Epsom salts are magnesium, and magnesium is important for many processes:

“Thus, one should keep in mind that ATP metabolism, muscle contraction and relaxation, normal neurological function and release of neurotransmitters are all magnesium dependent. It is also important to note that magnesium contributes to the regulation of vascular tone, heart rhythm, platelet-activated thrombosis and bone formation,” as explained in this paper.

On a related note, this study suggested that float tanks may be an effective treatment for anxiety, which makes sense based on our discussion about the stress response.

Music Therapy

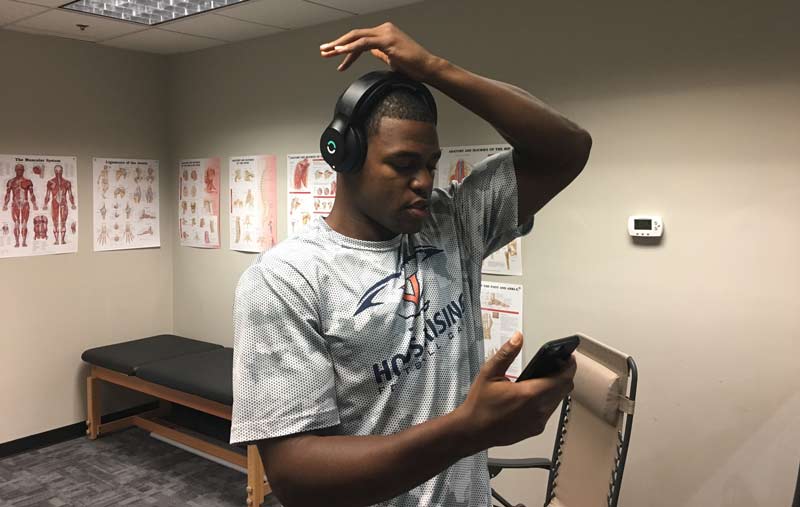

If you’re into music, this study showed a parasympathetic response to music. Consider spending some time relaxing with your favorite music or playing it while you nap. Perhaps incorporate deep breathing, meditation, and stretching to give yourself some real recovery time.

Power Napping

Napping is one of the most underrated interventions. Napping can help both the ANS and CNS to recuperate. Considering many athletes don’t get enough sleep at night, this could be a great place to start. Practice working your way into your nap with some guided breathing to maximize relaxation.

There are other ways to deal with stress and drive recovery. This list includes strategies I’ve heard from other coaches, witnessed myself, or found in the research.

Closing Thoughts on the Autonomic Nervous Systems

Creating a sympathetic environment should be fairly easy and straightforward, but if you feel like your athlete isn’t getting competition ready, there are a couple of things you could try. Many coaches like using a competitive warm up to stimulate a stress response. This study showed that mental imagery stimulated the sympathetic system similar to the actual competition. If all else fails, have your athletes picture the zombie apocalypse, and that should lead to lifetime PRs.

I am by no means an expert on the ANS or preparing your athletes for competition. I would love to hear other coaches’ feedback on systems that work for them or observations that they’ve made. This topic isn’t even on the radar for a lot of new coaches. Hopefully this opens up the dialogue and leads us to better results!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF