Brandon Howard is starting his second season at Texas Tech as an associate strength and conditioning coach for the Red Raider football program. Howard previously served one season at Ole Miss and as an assistant strength and conditioning coach at Utah State from 2016–17. He worked as a graduate assistant for the Aggies during the 2007–08 seasons.

Howard was also the Director of Sports Performance at Southeastern Louisiana from 2012–16, where he worked with both the football and baseball programs. Southeastern claimed the Southland Conference football title and appeared in the FCS playoffs during the 2013 and 2014 seasons, while the baseball program claimed the Southland crown in both 2014 and 2015 en route to making two NCAA Regional trips.

Freelap USA: You are very proficient with the Olympic lifts, as your own abilities are excellent. Can you share a few points on teaching the lifts that are less commonly talked about? Perhaps about fixing errors such as the barbell path and not keeping the bar close to the body?

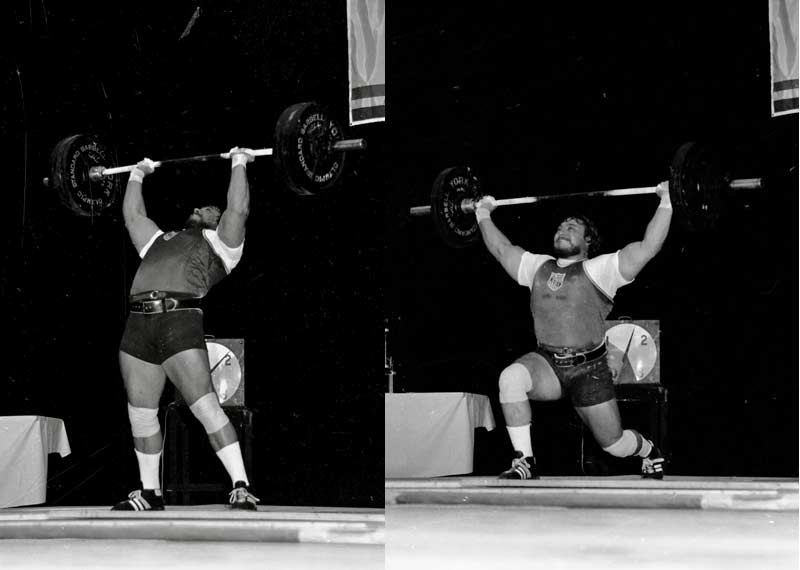

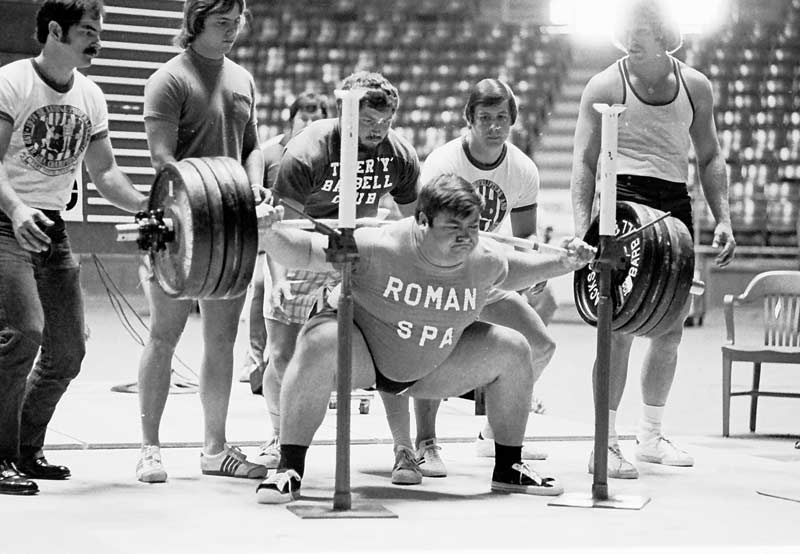

Brandon Howard: A big point of emphasis we use is the transition from Position 2 (Above Knee) to Position 1 (High Chest). We stress this transition to make sure that the bar stays close to the athlete, as well as to make sure that the torso is vertical for the shrug and the legs are loaded to provide sufficient power to move the bar into the receiving position.

Video 1. Weightlifting options are an opportunity for athletes to develop more than just power—they’re an opportunity to instill focus and concentration. Technical demands of the clean and snatch are excuses for underskilled coaches, not limitations of the exercise. You can teach the required technique for weightlifting with college football athletes without compromising other qualities.

One of the biggest cues that we tend to use with our athletes is “curl the wrists.” This helps the athlete and gives tactile feedback on keeping the bar close to the body during both pulls of the clean and snatch.

Freelap USA: Speed is a valuable asset in modern football. Could you share some of the changes you made in your philosophy over the years? What things do you do now that you didn’t do years ago? What things do you no longer do or not employ as much now?

Brandon Howard: Over the years I have been exposed to a variety of different methods for developing speed for athletic performance. I have been lucky to have worked with some of the best in the business when it comes to building speed. I take a no-nonsense approach when it comes to linear speed work, and that is sprint and sprint often, but with smart progression in distance and intensity.

I take a non-nonsense approach when it comes to linear speed work, and that is sprint and sprint often, but with smart progression in distance and intensity. Share on XThis is important to allow the athletes to progress and build high speed distance without the fear of soft tissue injuries. There is little that I have changed as far as the drills that I use; it’s more about the protocol in which they are introduced and progressed over time.

Freelap USA: When team coaches ask about conditioning, how do you communicate to them about being ready for the end of the game? Do you test your athlete’s fitness, or do you observe practice loads and make educated guesses as to their capacity for the game?

Brandon Howard: The biggest thing that we try to communicate to our coaches is the importance of training the specific energy systems that are vital for success. To be honest, the best way to get prepared for the game is to practice, and we also try and put our players into situations at the end of practice to mimic the way their mind and body will feel in an end game situation.

No, we do not do a “fitness test,” per se. We have a minimum standard that athletes must meet at the beginning of a training block. We use a player monitoring system throughout the year to keep track of high speed distances and explosive efforts. We also keep track of player loads from an injury mitigation standpoint, but not for actual work capacity.

We also try and put our players into situations at the end of practice to mimic the way their mind and body will feel in an end game situation. Share on XFreelap USA: Injuries, specifically non-contact types, are common today due to the extreme outputs of players. Do you have any non-typical recommendations for reducing groin or hamstring injuries?

Brandon Howard: The biggest recommendation I can make for trying to mitigate soft tissue injuries is for you to make sure you have a great plan for progressing your athlete’s movement throughout the training block. Making sure to progress intensity, distance, and frequency. If you have a sound plan, your athletes should have developed enough resiliency to reduce these issues. Stressing proper recovery, sleep, and hydration strategies will be a big help as well.

Video 2. Football requires different demands than track and field. While it’s great to work on speed, the size of the athlete is part of development momentum, an important quality for collision sports. In addition to power, durability is essential for athletes who are multidirectional and involved in contact sports.

Freelap USA: Over the course of a year, you spend time reviewing your athlete’s training. How do you make changes with the training each season? What ways do you think can help other coaches reflect on their training with more wisdom, so they keep what works and know where to look for areas that need to change?

Brandon Howard: Season review for strength coaches is a valuable part of the job. We have two important components of review that we conduct each year. They are:

- Always look at the team you have, as each team is its own group. You may be required to focus your time on a different aspect of training each year.

- You need to perform needs analysis on a yearly, or even a per-semester, basis. I don’t think this is done enough.

As a staff, we always take/make notes about the session, week, and/or block that we have just completed. We see what we liked and what worked well, and we do what we can to continue those training stimuli. We also remove drills, lifts, or any other modalities that we feel are not beneficial for the current team.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF