[mashshare]

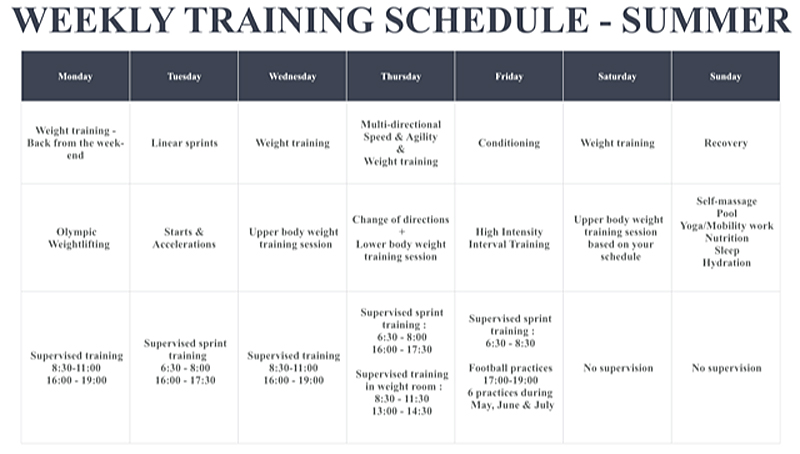

During the winter months, most off-season training activities for the athletic development program of a Canadian university football team are performed indoors either in the weight room or on the track. These first 12-15 weeks of the annual training program serve both as an introduction and a foundation. With summer just around the corner and no more snow on the turf, football programs transition to more sport-specific athletic development activities. This second of two articles provides insight into the summer running program and in-season training program of a Canadian university football team.

Summer Preparation

Canadian football rules create additional requirements for running, change of direction and agility, and overall conditioning, as explained in Part 1 of this series, which we need to consider during summer training.

Weight Training

Our first training session of the week continued to focus on variations of the Olympic weightlifting movements as well as bilateral exercises like squats, hex bar deadlifts, and lunges. At this point, however, we introduced methods such as clusters, rest-pause, or contrast training (alternating between a heavy and low-velocity movement followed by a light and high-velocity movement) and progressed our athletes over the course of the summer.

Sprints, Starts, and Accelerations

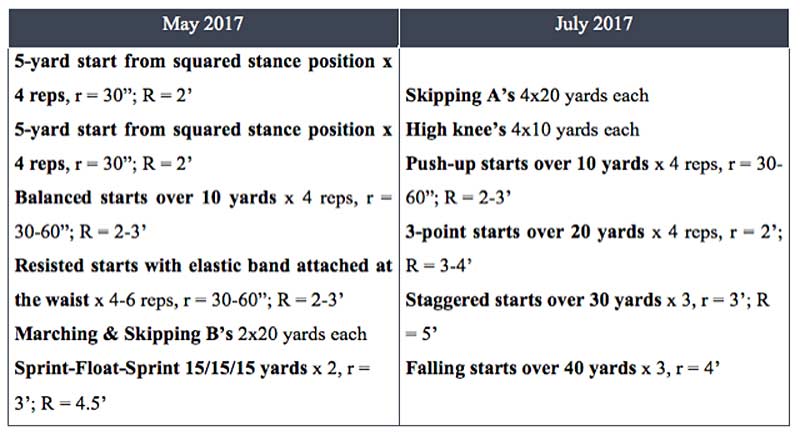

On Tuesdays, we still focused on linear accelerations and sprint work from different starting positions but increased the overall distance of the repetitions. Most summer drills were simply progressions of those performed during the winter. For example, while the winter distances were under 20 meters indoor because of the track surface, in the summer we wanted to cover distances of 30-40 yards on the turf regularly for most positions except maybe the offensive linemen.

We exposed the skill positions—wide receivers, running backs, defensive backs, and linebackers—to more maximal velocity sprints instead of only focusing on short accelerations. As suggested by many coaches, the emphasis for this training session was on quality rather than quantity, so the overall running distances were kept between 300-450 total yards with longer rest intervals between repetitions.

As you can see, we had limited access to training tools such as sleds and technology that could provide resistance or assistance during sprinting. When we wanted to provide a little bit of overload, we added resistance bands, found a shallow hill around campus, or simply manipulated the starting positions.

Change of Direction and Agility

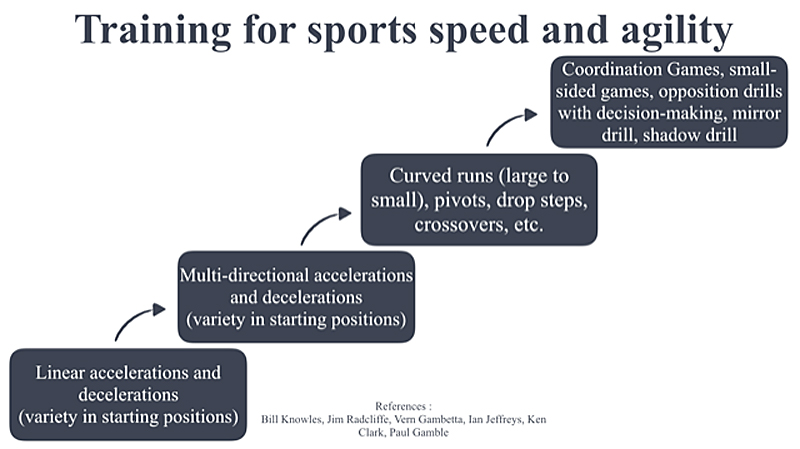

Thursdays targeted change of direction and agility. While agility is defined as the “skills and abilities needed to change direction, velocity, or mode in response to a stimulus,”3 there is a place for some pre-planned movements to teach acceleration, deceleration, and proper body positioning. These include power cuts, speed cuts, Pro-Agility, and 3-cone drills. We, therefore, introduced a wider variety of movements and exercises during these training sessions and progressed from closed or pre-planned drills to situations where the players had to react to a stimulus.

Examples of movements and drills performed include:

- different types of plyometrics—pogo jumps, lateral bounds

- posture drills—Sway drill

- directional acceleration drills—side step to sprint, side shuffle to sprint, etc.

- classic change of direction drills—Pro-Agility, 3-cone drills

- reactive agility—partner chase, mirror drill, etc.

We included pre-planned exercises for out-of-town players who might not be able to train in small groups and thus be exposed to reactive agility drills. It was not the ideal scenario but was a good alternative for these kids. Following this training session, we completed a lower body training session focusing on speed-strength through movements such as snatches, ballistic jumps, plyometrics, and core work for 2-3 sets only.

Conditioning

On Fridays, we had a third training session on the turf focused on conditioning. We set up the sessions to be performed with no equipment, except for cones and a stopwatch. For the first 3-week mesocycle, the session consisted of tempo runs. Nothing too fancy: run the length of the field (110 yards) in about 22-23 seconds and walk the width of the field. Repeat that for a total of 18-24 reps. We modified the length of the runs based on the different playing positions with linemen running only 55 yards. This tempo work provided a good and smooth introduction to the high-intensity interval training (HIIT) that followed.

#Tempo work provides a smooth transition to high-intensity interval training, says @xrperformance. Share on XFor the rest of the summer, the Friday conditioning session centered on HIIT with 10 seconds of work and 10 seconds of rest (10”/10”). We started with 3 sets of 10 reps with 3-5 minutes of passive rest between sets and progressed to 6 sets of 10 reps near the end of July, based on the number of plays during a Canadian university football game.

It’s possible to prescribe accurate running distances if you test at the beginning of the summer using Martin Buchheit’s 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test, for example. In our case, we told athletes that they should be able to complete the same running distances from the first to the last repetition of a set. We also varied the running over the course of the summer to include linear, shuttle, zigzag, or runs with a 45° or 90° change of direction to provide different training stimulus.

Team Practices

We also scheduled six team practices over the course of the summer. The practices were a good opportunity to complete more technical and tactical work with the football coaches and also were important to get the players ready for the season. We simply could not afford to lose 6 conditioning sessions over the course of 12 weeks. So we looked at “competition modeling” to replicate and adapt what happens during a game in the practice setting.

We looked at the work of Plisk & Gambetta4 and some in-house statistics to come up with work:rest ratios as well as sets and reps that replicated game situations. For example, we divided practice 1 into 3 quarters of 3 sets of 4 plays (total of 36 plays) with 40 seconds of rest between each play and 4 minutes between every quarter for a 1:8 work:rest ratio.

We then manipulated these parameters over the six practices to match game demands. For example, the last practice consisted of 4 quarters of 4 sets of 5 plays with 25 seconds of rest between each play and 3 minutes between each quarter. The football coaches designed the different drills according to position and coached the technical demands associated with each drill.

Training During the Competitive Season

During the competition season, the priority shifted from athletic development to technical and tactical mastery of the game. We also prioritized the recovery process following the game. It’s important, however, to maintain some sort of athletic development work over the course of the competition season.

Weight Training

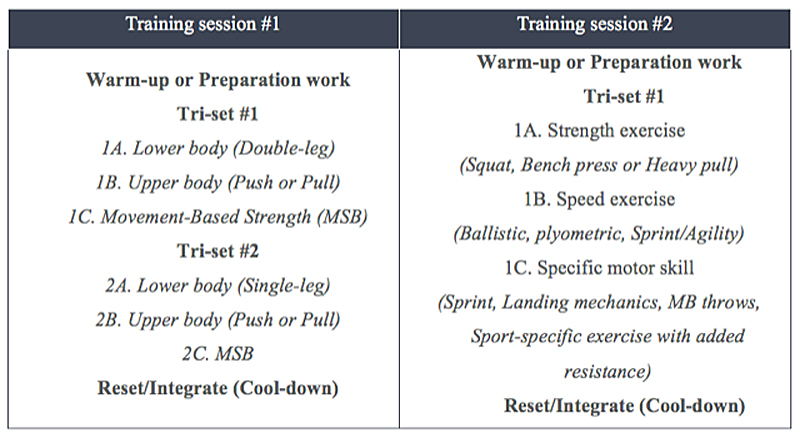

In our case, we divided the competition season into three smaller training blocks of two weekly training sessions. Using the same terminology proposed by Stuart Yule,5 we labeled the first training block Prepare and started with training camp. Because of the demands of training camp, we decreased the intensity of the work performed in the weight room and used 6-10 reps for the main exercises of session 1.1

The second training block, Advance, reduced the number of repetitions (3-5 reps) performed during the first training session to focus a bit more on maximal strength qualities. Conquer, the last training block, focused on maximal power using different variations of loaded jumps—barbell jump squats, Hex bar jumps, kettlebell jump squats. The exercise selection of these weekly training sessions was very similar to limit unnecessary muscle soreness related to the novelty of an exercise.

Below is an example of exercises we used for training session 1 of the first in-season training block. Players usually performed this training session Tuesday for 2 sets with 15-30 seconds intra-set recovery and 1-2 minutes of inter-set recovery.

Session 1 of the First In-Season Training Block

- Tri-set 1A: barbell jump shrug or barbell front squat or Hex bar deadlift

- Tri-set 1B: 1-arm low incline dumbbell bench press or 1-arm dumbbell row

- Tri-set 1C: hip lock variation using body weight or light resistance

- Tri-set 2A: dumbbell lunges or dumbbell step-ups

- Tri-set 2B: half-kneeling 1-arm overhead press or chin-ups

- Tri-set 2C: medicine ball core rotations

Approximately 24-48 hours before the next match, players again performed a short 30-minute resistance training session. It was very important to educate and remind the athletes of the session’s main objective.

Reflections on the Off-Season Preparation

As I mentioned in my article on reflective coaching practices, “it is the capacity of coaches to practice, reflect and then learn from their experience that is central to developing coaching effectiveness.”2 After implementing the off-season program, we noticed increases in lifts, including 1RM chin-ups, bench presses, and 30-15 IFTs.

After the off-season program, we saw increases in lifts: 1RM chin-ups, bench presses, & 30-15 IFTs, says @xrperformance. Share on XLike most football programs, we experienced a few injuries over the course of the preparation period, and I should have done a better job on timing the introduction of some of the drills we did. For example, we had a few players complain of back irritation during the winter. Like many coaches, I like to implement different variations of the squat at least once a week in my programming.

But due to the requirements of winter training camp, I tended to rush the progression of the movement’s relationship with performance in short sprints which characterizes the game of football. I must learn to be more patient to allow the body the opportunity to adapt to the exercise and the load.

I also need to better communicate to players the importance of setting a proper movement foundation before looking at more advanced training methods. As soon as we started implementing curved runs in our change of direction sessions, players—especially linemen—started complaining of ankle discomfort and pain. Again, I need to provide better progressions and options to the players based on each individual’s needs and position not only for physical preparation but also for competition.

Performance is also about what happens on the football field. While the team struggled this past season, it remained somewhat healthy. On offense, for example, the offensive coordinator commented a few times over the course of the season that he had never seen so few injuries in his 20-year career at this level. On the offensive line, all five starters played all nine games of the season. Let’s also give credit to the offensive line coach who managed the content of his training sessions very well, though he did not foresee having all offensive line starters available every week.

Overall, it’s not about how much you lift, how big you are, or how fast you run, but rather how you contribute to the team’s success on a daily basis. Both the off-season and in-season training programs we implemented met this criterion.

Conclusion

It’s quite challenging to provide a detailed and comprehensive look at the different components of such a program from lifting to sprinting to conditioning, as all these components should be integrated. It’s also very important to understand the context in which you will implement such a program because this will certainly drive many choices that you’ll make in your planning and programming. I hope that these two articles provide a better understanding of Canadian football, particularly at the university level.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Allerheiligen, B. (2003). In-Season Strength Training for Power Athletes. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 25(3), 23‑28.

2. Knowles, Z., Borrie, A., & Telfer, H. (2005). Towards the reflective sports coach : issues of context, education and application. Ergonomics, 48(November), 1711‑1720.

3. Nimphius, S., Callaghan, S. J., Bezodis, N. E., & Lockie, R. G. (2018). Change of Direction and Agility Tests : Challenging Our Current Measures of Performance. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 40(1), 26-38.

4. Plisk, S. S., & Gambetta, V. (1997). Tactical Metabolic Training: Part 1. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 19(2), 44‑53.

5. Yule, S. (2014). Maintaining an In-Season Conditioning Edge. Dan Lewindon & David Joyce (Éd.), High-Performance Training for Sports(p. 301‑318). Windsor, Ontario: Human Kinetics.