[mashshare]

Athletes who are bigger, stronger, and faster have been the goal of athletic development for American football players for many years. Just north of the border, Canadian football also seeks players who are bigger, stronger, and faster. Due to differences in the sport, however, Canadian football teams cannot blindly copy the training programs from some of the most popular football programs in the United States, especially at the college level.

This is the first of two articles providing insight into the off-season athletic development program of a Canadian university football team.

Key Differences in Canadian and American Football

Much like American football, Canadian football is an intermittent collision sport where players require well-developed physical qualities such as strength, power, speed, agility, and anaerobic endurance. However, there are major differences between both sports that make Canadian football a very different game.

- The size of the field is longer (150 yards) and wider (65 yards) with end zones 20 yards deep and 110 yards separating both end zones.

- Canadian football is a 3-down game while American football is 4, which puts more emphasis on the Canadian passing game.

- All offensive backfield players except the quarterback may move in any direction to confuse the defense as long as they are behind the line of scrimmage at the snap.

- One yard separates the offensive and defensive line before the snap of the ball, which provides more opportunities for coaches to implement stunts and various movements on the defensive side of the ball. This creates additional requirements for change of direction and agility.

- While special team players often run the most during NFL games, Canadian special team players are required to run even more at both the college and professional levels.

| U Sports 2017 Football season | |

| Game #1 | 38 |

| Game #2 | 42 |

| Game #3 | 37 |

| Game #4 | 34 |

| Game #5 | 37 |

| Game #6 | 46 |

| Game #7 | 39 |

| Game #8 | 45 |

| Game #9 | 34 |

| Average number of ST plays per game | 39 |

| Total number of ST plays during the season | 352 |

It’s also worth mentioning that, because the goal posts are placed directly above the end zones, a missed field goal may give the special teams an opportunity to take the ball and return it for a touchdown. This can’t happen in American football because the goal posts stand at the back of the end zones. Here is an example of a 129-yard missed field goal return touchdown.

Different rules and play increase the running demands of #CanadianFootball compared to the US game, says @xrperformance. Share on XThese differences in rules and play increase the running demands in Canadian football, and we need to take them into account when planning the off-season program. One research study, for example, found the total distance traveled during a game by non-linemen (WR, DB, LB) was about 4,141.3 meters.4 For pre-season practices, however, another study reported distances of only 2,573 ± 489 meters for these positions.2 We did our own research using GPS during eight games in the 2016 season and nine games in the 2017 season and found the WR and RB covered total distances of 6,321± 917 meters and 6,155 ± 509 meters, respectively.

With a better understanding of the demands of these positions, we had to adjust our training program so we could better prepare our student-athletes to meet the game’s requirements.

Preparing During the Winter Semester: Focusing on the Weight Room

The off-season program usually starts the first week of January when the players get back on campus. At this time of the year, there are about 90-100 players on the team. The first week has very few training activities scheduled since players meet with their coaches for team meetings and attend class. For some recruits, the first week can be a little stressful as they transition from CEGEP to university. From an athletic development perspective, it’s a perfect opportunity to introduce the philosophy and goals of the training program and perform any movement screening. Training usually resumes during the second week of January.

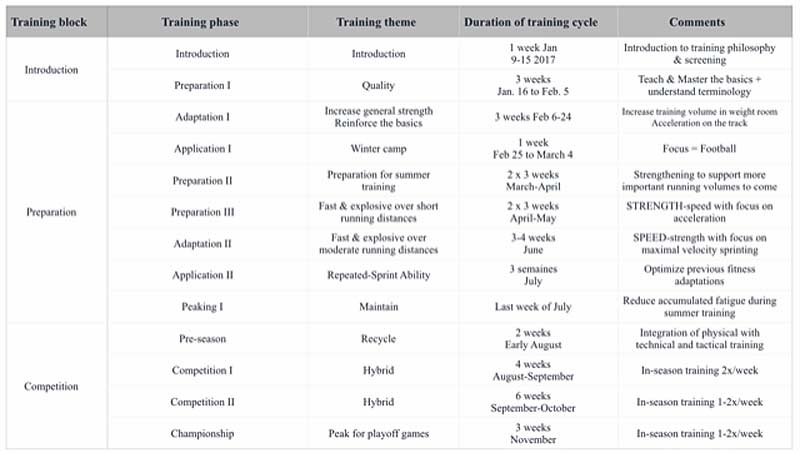

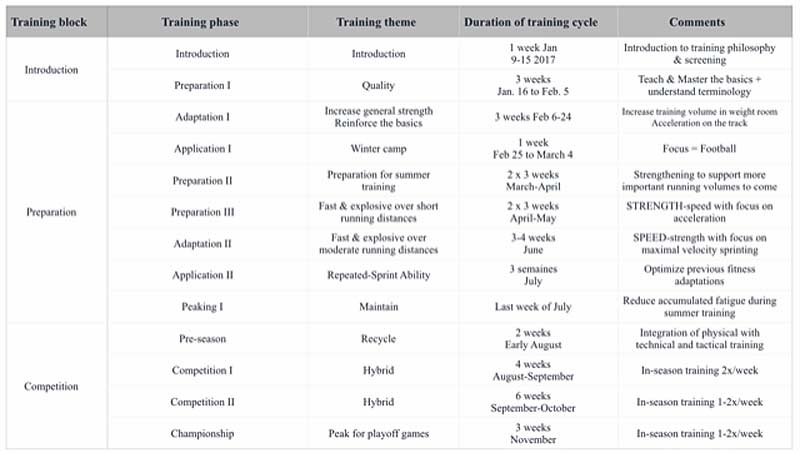

While I was Head Strength & Conditioning coach for a Canadian university football team, we divided winter training into four 3-week cycles. The first two 3-week cycles introduced the student-athletes to the philosophy behind the athletic development program and the different exercises they would perform. We also made sure that they executed the exercises properly.

The main training themes for the winter semester, right before the training camp, were:

- Teaching and mastering the basic movements and understanding the terminology used

- Progressively increasing training volume in the weight room

On the track, we began by focusing on proper running mechanics and postures and working on starts and accelerations using a short-to-long approach. Training was also needed to prepare the athletes for the increased demands of the winter training camp, which usually took place only weeks later during March break.

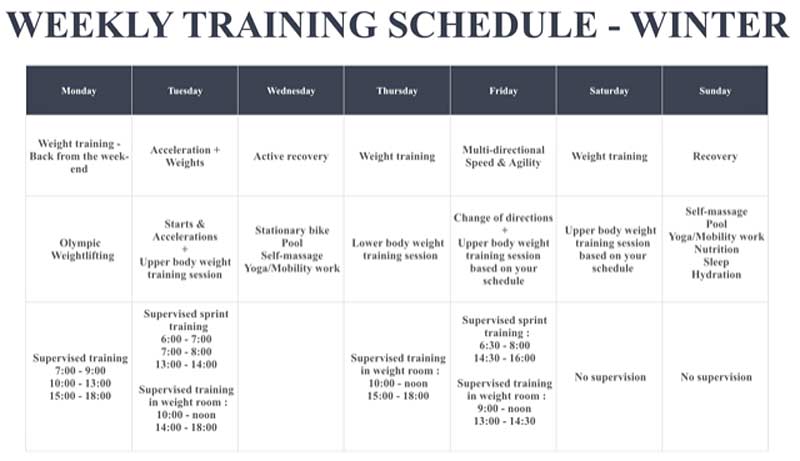

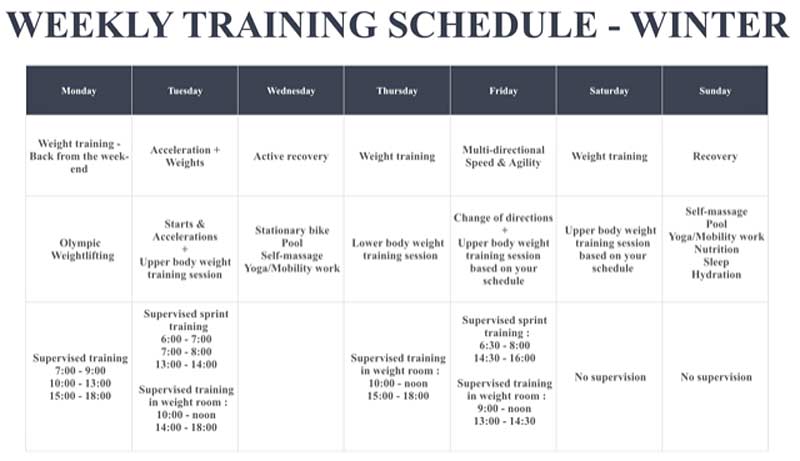

A training week during the winter semester was divided into four weight training sessions and two running sessions on the track. Student-athletes trained in the weight room on Monday. On Tuesday, they had two training sessions, one on the track and another in the weight room. They got Wednesday off to perform technical work with their position coach or participated in active recovery (stretching, pool, stationary bike). We repeated the same pattern for Thursday and Friday, with the athletes having the option to perform the last weight training session on Friday or Saturday.

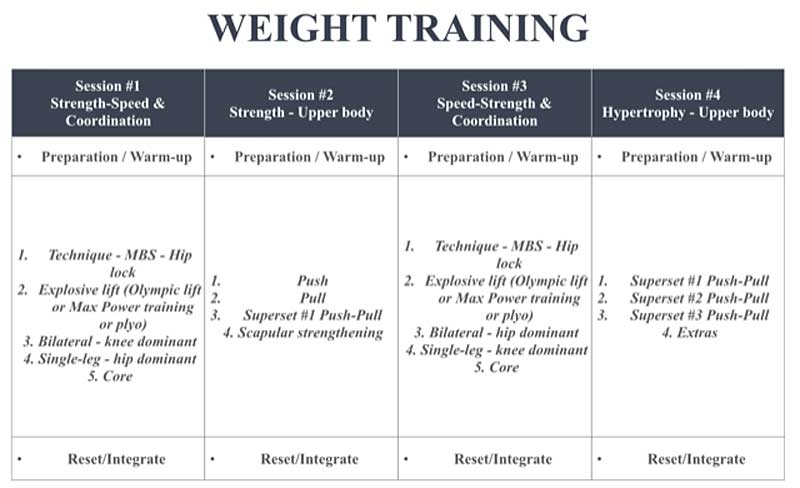

This last training session mostly focused on upper body muscle hypertrophy because college football rules involve more collisions than professional Canadian football teams; professional teams are contractually obliged to minimize the amount of contact per training week thus restricting practices to helmets only.

After the winter training camp, the team benefited from a week off before resuming the last two 3-week cycles, which would lead them to the start of winter semester exams. The training themes during this time built on the previous training phases and prepared the players for the increased sprinting and running demands associated with summer training. Despite the need to prepare for these increased demands, the volume of sprinting on the track varied little, and overall volumes were kept quite low.

One of the challenges in Canadian university football during the winter is that we never know when we’ll have access to the outdoor football field because of the snow and cold temperatures. Also, increasing the sprinting distances and volumes on the track can lead to a lot of sore ankles, sore knees, and shin splints. During the exam period, we reduced the number of training activities so they could focus on school work.

Individualization for 100+ Athletes

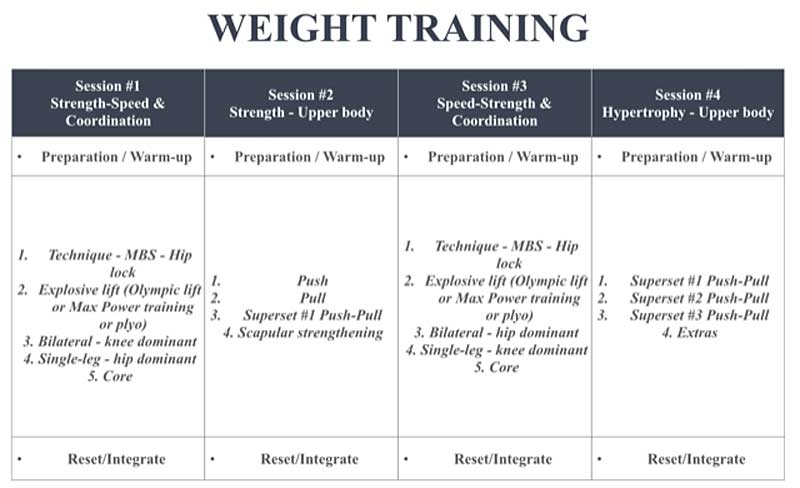

At this point, training was in full swing with large groups of athletes training at the same time. Athletes performed various movements found in most athletic development programs for football, namely variations of the Olympic lifts like cleans and snatches, squats, lunges, presses, pulls, and various exercises targeting the core musculature.

Even though individualizing the training program to fit the needs of each athlete is an important principle, it’s virtually impossible to individualize the training for over 100 student-athletes when they do most activities in small groups. An interesting way to program training at this point is to use general exercise categories and allow the athlete and the strength and conditioning coach to choose exercises based on the athlete’s needs. Examples include:

- Movement-based strength exercises like various progressions of the hip lock using only body weight, elastic bands, or weight plates

- Explosive lifts (classical Olympic lifts or variations like dumbbell or barbell jump shrug), jump squat, dumbbell snatches, and plyometrics

- Bilateral exercises such as squats and deadlifts and variations including the Hex bar deadlift, barbell front squats, kettlebell squats, and Romanian deadlift

- Single-leg lower body exercises like lunges, step-ups, single-leg squats, and single-leg deadlifts

- Pushing exercises, including bench press, overhead press, and push-ups

- Pulling exercises like chin-ups, inverted rows, and dumbbell rows

- Core exercises such as various planks, Pallof press variations, landmine work, and medicine ball work

We chose exercises that best fit the goals of the session based on:

- The athlete’s needs, training experience, position, and injury history

- The theme of the current session

- The requirements of that athlete’s position

- What the athlete would do on the track the following day—exercise selection would be different if the focus of the running session was going to be on acceleration or change of direction

A Few Words on Sprinting and Change of Direction

As mentioned previously, most of the training on the track during the winter semester focused on starts and accelerations. On Tuesday, we focused on linear starts and acceleration work. On Friday, the focus was on starts and acceleration again but from a multidirectional perspective. Rarely would we run sprints above 20 or 30 meters because of the indoor track.

Here is an example of a training session focused on linear acceleration during the 3-week cycle preceding winter training camp.

- Exercise 1. Technique/Arm action—Big to small arm swings x 1-2 sets

- Exercise 2. Technique/Posture—Marching A’s 1 x 2-4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 3. Technique/Posture—Skipping A’s 1 x 4 x 20 meters

- Exercise Technique/Posture—High knees 1 x 4 x 20 meters

- Exercise 5. Acceleration 0-10 meters—Push-up starts 1 x 4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 6. Acceleration 0-10 meters—Half-kneeling starts 1 x 4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 7. Acceleration 0-20 meters—3-point starts 1 x 3 x 20 meters

When we felt the need to break the routine and provide a bit of novelty to the training, we booked the dancing studio where we could roll out the gymnastic mats. During those sessions, we performed various movements such as stick mobility exercises, a modified version of Josh Hingst’s barefoot jump rope routine, various plyometrics, and tumbling movements. We finished the training session with a “Competitive Coordination Game” à la Bill Knowles. We had these training sessions about once a month during the winter semester.

Conclusion

This article provides a glimpse of a Canadian university football team’s off-season training program. There are major differences between Canadian and American college football programs that we need to address when examining a Canadian team’s training program. We also have to design a program around the different activities that make up the life of a student-athlete including the specific demands of the sport, human and financial resources, academic environment, and weather.

In Part 2, we’ll look at the summer training we performed to better prepare the athletes for the increased running and conditioning demands of Canadian football.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Camiré, M., & Trudel, P. (2013). Using High School Football to promote Life Skills and Student Engagement: Perspectives from Canadian Coaches and Students. World Journal of Education, 3(3), 40‑ http://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v3n3p40.

- DeMartini, J., Martschinske, J., Casa, D., Lopez, R., Ganio, M., Walz, S., & Coris, E. (2011). Physical demands of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football players during preseason training in the heat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,25(11), 2935‑doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231a643.

- Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (2014). Rapport annuel 2013-2014. Consulté à l’adresse http://rseq.ca/lerseq/rseqrapportsannuels/.

- Wellman, A. D., Coad, S. C., Goulet, G. C., & McLellan, C. P. (2016). Quantification of Competitive Game Demands of NCAA Division I College Football Players Using Global Positioning Systems. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(1), 11-19. http://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001206.

How to Plan the Off-Season in Canadian University Football Part 1: Winter Training

[mashshare]

Athletes who are bigger, stronger, and faster have been the goal of athletic development for American football players for many years. Just north of the border, Canadian football also seeks players who are bigger, stronger, and faster. Due to differences in the sport, however, Canadian football teams cannot blindly copy the training programs from some of the most popular football programs in the United States, especially at the college level.

This is the first of two articles providing insight into the off-season athletic development program of a Canadian university football team.

Key Differences in Canadian and American Football

Much like American football, Canadian football is an intermittent collision sport where players require well-developed physical qualities such as strength, power, speed, agility, and anaerobic endurance. However, there are major differences between both sports that make Canadian football a very different game.

- The size of the field is longer (150 yards) and wider (65 yards) with end zones 20 yards deep and 110 yards separating both end zones.

- Canadian football is a 3-down game while American football is 4, which puts more emphasis on the Canadian passing game.

- All offensive backfield players except the quarterback may move in any direction to confuse the defense as long as they are behind the line of scrimmage at the snap.

- One yard separates the offensive and defensive line before the snap of the ball, which provides more opportunities for coaches to implement stunts and various movements on the defensive side of the ball. This creates additional requirements for change of direction and agility.

- While special team players often run the most during NFL games, Canadian special team players are required to run even more at both the college and professional levels.

| U Sports 2017 Football season | |

| Game #1 | 38 |

| Game #2 | 42 |

| Game #3 | 37 |

| Game #4 | 34 |

| Game #5 | 37 |

| Game #6 | 46 |

| Game #7 | 39 |

| Game #8 | 45 |

| Game #9 | 34 |

| Average number of ST plays per game | 39 |

| Total number of ST plays during the season | 352 |

It’s also worth mentioning that, because the goal posts are placed directly above the end zones, a missed field goal may give the special teams an opportunity to take the ball and return it for a touchdown. This can’t happen in American football because the goal posts stand at the back of the end zones. Here is an example of a 129-yard missed field goal return touchdown.

Different rules and play increase the running demands of #CanadianFootball compared to the US game, says @xrperformance. Share on XThese differences in rules and play increase the running demands in Canadian football, and we need to take them into account when planning the off-season program. One research study, for example, found the total distance traveled during a game by non-linemen (WR, DB, LB) was about 4,141.3 meters.4 For pre-season practices, however, another study reported distances of only 2,573 ± 489 meters for these positions.2 We did our own research using GPS during eight games in the 2016 season and nine games in the 2017 season and found the WR and RB covered total distances of 6,321± 917 meters and 6,155 ± 509 meters, respectively.

With a better understanding of the demands of these positions, we had to adjust our training program so we could better prepare our student-athletes to meet the game’s requirements.

Preparing During the Winter Semester: Focusing on the Weight Room

The off-season program usually starts the first week of January when the players get back on campus. At this time of the year, there are about 90-100 players on the team. The first week has very few training activities scheduled since players meet with their coaches for team meetings and attend class. For some recruits, the first week can be a little stressful as they transition from CEGEP to university. From an athletic development perspective, it’s a perfect opportunity to introduce the philosophy and goals of the training program and perform any movement screening. Training usually resumes during the second week of January.

While I was Head Strength & Conditioning coach for a Canadian university football team, we divided winter training into four 3-week cycles. The first two 3-week cycles introduced the student-athletes to the philosophy behind the athletic development program and the different exercises they would perform. We also made sure that they executed the exercises properly.

The main training themes for the winter semester, right before the training camp, were:

- Teaching and mastering the basic movements and understanding the terminology used

- Progressively increasing training volume in the weight room

On the track, we began by focusing on proper running mechanics and postures and working on starts and accelerations using a short-to-long approach. Training was also needed to prepare the athletes for the increased demands of the winter training camp, which usually took place only weeks later during March break.

A training week during the winter semester was divided into four weight training sessions and two running sessions on the track. Student-athletes trained in the weight room on Monday. On Tuesday, they had two training sessions, one on the track and another in the weight room. They got Wednesday off to perform technical work with their position coach or participated in active recovery (stretching, pool, stationary bike). We repeated the same pattern for Thursday and Friday, with the athletes having the option to perform the last weight training session on Friday or Saturday.

This last training session mostly focused on upper body muscle hypertrophy because college football rules involve more collisions than professional Canadian football teams; professional teams are contractually obliged to minimize the amount of contact per training week thus restricting practices to helmets only.

After the winter training camp, the team benefited from a week off before resuming the last two 3-week cycles, which would lead them to the start of winter semester exams. The training themes during this time built on the previous training phases and prepared the players for the increased sprinting and running demands associated with summer training. Despite the need to prepare for these increased demands, the volume of sprinting on the track varied little, and overall volumes were kept quite low.

One of the challenges in Canadian university football during the winter is that we never know when we’ll have access to the outdoor football field because of the snow and cold temperatures. Also, increasing the sprinting distances and volumes on the track can lead to a lot of sore ankles, sore knees, and shin splints. During the exam period, we reduced the number of training activities so they could focus on school work.

Individualization for 100+ Athletes

At this point, training was in full swing with large groups of athletes training at the same time. Athletes performed various movements found in most athletic development programs for football, namely variations of the Olympic lifts like cleans and snatches, squats, lunges, presses, pulls, and various exercises targeting the core musculature.

Even though individualizing the training program to fit the needs of each athlete is an important principle, it’s virtually impossible to individualize the training for over 100 student-athletes when they do most activities in small groups. An interesting way to program training at this point is to use general exercise categories and allow the athlete and the strength and conditioning coach to choose exercises based on the athlete’s needs. Examples include:

- Movement-based strength exercises like various progressions of the hip lock using only body weight, elastic bands, or weight plates

- Explosive lifts (classical Olympic lifts or variations like dumbbell or barbell jump shrug), jump squat, dumbbell snatches, and plyometrics

- Bilateral exercises such as squats and deadlifts and variations including the Hex bar deadlift, barbell front squats, kettlebell squats, and Romanian deadlift

- Single-leg lower body exercises like lunges, step-ups, single-leg squats, and single-leg deadlifts

- Pushing exercises, including bench press, overhead press, and push-ups

- Pulling exercises like chin-ups, inverted rows, and dumbbell rows

- Core exercises such as various planks, Pallof press variations, landmine work, and medicine ball work

We chose exercises that best fit the goals of the session based on:

- The athlete’s needs, training experience, position, and injury history

- The theme of the current session

- The requirements of that athlete’s position

- What the athlete would do on the track the following day—exercise selection would be different if the focus of the running session was going to be on acceleration or change of direction

A Few Words on Sprinting and Change of Direction

As mentioned previously, most of the training on the track during the winter semester focused on starts and accelerations. On Tuesday, we focused on linear starts and acceleration work. On Friday, the focus was on starts and acceleration again but from a multidirectional perspective. Rarely would we run sprints above 20 or 30 meters because of the indoor track.

Here is an example of a training session focused on linear acceleration during the 3-week cycle preceding winter training camp.

- Exercise 1. Technique/Arm action—Big to small arm swings x 1-2 sets

- Exercise 2. Technique/Posture—Marching A’s 1 x 2-4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 3. Technique/Posture—Skipping A’s 1 x 4 x 20 meters

- Exercise Technique/Posture—High knees 1 x 4 x 20 meters

- Exercise 5. Acceleration 0-10 meters—Push-up starts 1 x 4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 6. Acceleration 0-10 meters—Half-kneeling starts 1 x 4 x 10 meters

- Exercise 7. Acceleration 0-20 meters—3-point starts 1 x 3 x 20 meters

When we felt the need to break the routine and provide a bit of novelty to the training, we booked the dancing studio where we could roll out the gymnastic mats. During those sessions, we performed various movements such as stick mobility exercises, a modified version of Josh Hingst’s barefoot jump rope routine, various plyometrics, and tumbling movements. We finished the training session with a “Competitive Coordination Game” à la Bill Knowles. We had these training sessions about once a month during the winter semester.

Conclusion

This article provides a glimpse of a Canadian university football team’s off-season training program. There are major differences between Canadian and American college football programs that we need to address when examining a Canadian team’s training program. We also have to design a program around the different activities that make up the life of a student-athlete including the specific demands of the sport, human and financial resources, academic environment, and weather.

In Part 2, we’ll look at the summer training we performed to better prepare the athletes for the increased running and conditioning demands of Canadian football.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Camiré, M., & Trudel, P. (2013). Using High School Football to promote Life Skills and Student Engagement: Perspectives from Canadian Coaches and Students. World Journal of Education, 3(3), 40‑ http://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v3n3p40.

- DeMartini, J., Martschinske, J., Casa, D., Lopez, R., Ganio, M., Walz, S., & Coris, E. (2011). Physical demands of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I football players during preseason training in the heat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,25(11), 2935‑doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231a643.

- Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (2014). Rapport annuel 2013-2014. Consulté à l’adresse http://rseq.ca/lerseq/rseqrapportsannuels/.

- Wellman, A. D., Coad, S. C., Goulet, G. C., & McLellan, C. P. (2016). Quantification of Competitive Game Demands of NCAA Division I College Football Players Using Global Positioning Systems. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(1), 11-19. http://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001206.

Leave the first comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.