As a strength and conditioning coach, I am well aware of the value of recognizing those experts who not only help propel me forward in my field, but also help me to assist the coaches and athletes who I work with on a daily basis to surpass their personal conditioning goals. For years, SimpliFaster has been bookmarked in my browser.

I have read articles from many trainers that helped inspire me and caused me to feel that tug between what I think I already know and what I undoubtedly want to know more about because my curiosity has been aroused. I appreciate that SimpliFaster offers a repository of articles in a digital society where many people view blogs as an antiquated way to gather information.

SimpliFaster, in my eyes, is a hub for people in the sports medicine field to share their expertise, trials, and successes. The articles that I choose to read provide me with a sense of belonging in my field. I actually told myself last summer that I would aspire to write an article or two for SimpliFaster, and since I have been granted the opportunity to do so, I decided to share seven ways that SimpliFaster has helped me as a coach.

1. Providing Access to Other Coaches

There often seems to be a gap between colleagues and between their practices, so a bridge is needed to span this divide. SimpliFaster has given me personal access to coaches through the articles they have written. When you read about other coaches’ training methodologies and recognize similarities with your own, it adds needed confirmation that is sometimes forgotten during the training of others. Confirmation combats the occasional uncertainty of training.

These articles, backed by science, are relatable because of shared experiences and have helped me determine the most efficient way of training for my work at DeKalb High School. This is especially true for me when being charged with changing the athletic interface of a high school through strength and conditioning. Raising a family and training athletes are tasks that keeps me busy and apart from other coaches who are outside of my coach’s circle. SimpliFaster fills that void.

I follow quite a few coaches on Twitter whose articles I first read on SimpliFaster. To say that I have received encouragement through their posts and articles would be an understatement. Iron sharpens iron. A friend sharpens a friend. These are two statements in which I have always believed.

Publications on the SimpliFaster blog keep me sharp by reminding me to adjust training habits and remain current with data, says @__JoshuaCollins. Share on XPublications on the SimpliFaster blog keep me sharp by reminding me to adjust training habits and remain current with data. Being able to access articles from high school strength and conditioning coaches helps me analyze parallels and differences. After reading his interview, I reached out to Scott Meier, a physical education teacher and strength and conditioning coach at Farmington High School, with questions about testing metrics in his strength and conditioning classes. He was very accessible and answered every question thoroughly.

If you want answers, there are coaches willing to share information and provide research to back up the data. I may not agree with everything, but it is not about my compliance—it is about forming the relationships to have conversations that lead to practical information for the people you train. I use some of the same principles in strength and conditioning training that I learned from other experts in the field. Learn things that are foreign to you to add stimuli and have high intent when trying to help others execute.

2. Supporting Athletics Without the Kill Intent

SimpliFaster has opened the door for trainers to collaborate with each other. In a field that is overshadowed by mainstream glitz and glamour, I found out there are more people in my shoes than not. Many strength coaches who use various social media platforms are linked to SimpliFaster. They are also approachable.

I came across the Twitter page of Mike Whiteman at Hounds Speed. I appreciated his post about the science of movement and how he actually demonstrated what he speaks about throughout the exercise. He used the Probotics Just Jump System, which I own, and made workout videos in his garage similar to what I have done. I directly messaged him to ask where he got his bumper plates and barbells, and those questions later turned into me wanting to learn more about his speed-driven workouts.

In addition, his age is somewhat similar to mine (36), yet he still moves with a high force rate. Usually on breaks from work I arrange times to shadow some coaches, but since COVID-19 happened during my spring break, I thought I would virtually reach out to Mike with additional questions.

Communicating with Mike Whiteman on programming and being “twitchy” has revealed to me the personal passiveness in my workouts. I have been doing a program of his for five weeks now, and I feel great. A fair question here would be, “If things are great, what’s the issue?” The issue is that my intent was not as high as it should have been, and I had been satisfied with just doing the movements. I acknowledge that it is great in terms of the recognition that I completed a workout, but that is only the surface level for force development. My aim would be more efficient with a focus on adaptation through dynamic movement. Intent is a linchpin for adaptation, and I was lacking it.

Whiteman’s program that I have been doing is a five-day split with three intense days. This program, along with the expertise he shared with me, has enabled me to shadow him virtually. Throughout these five weeks, it dawned on me that I would never have realized that my intent was low, and that stress should be bleeding out through these violent movements. Intent can make an objective clear-cut, whereas I might have missed the objective due to my passivity.

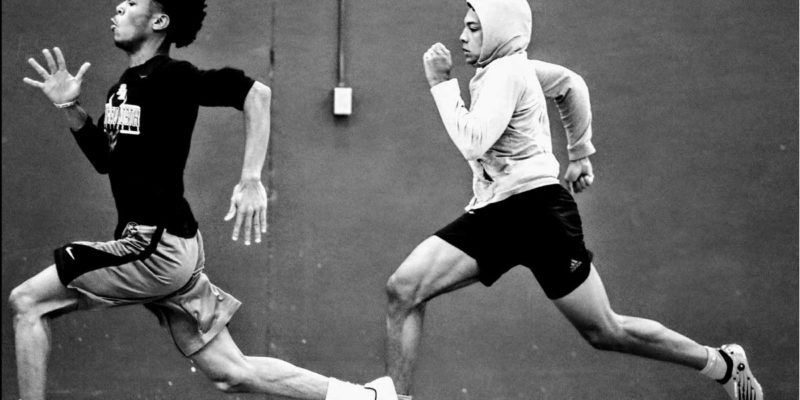

Recording workouts has been a way for me to communicate and tweet videos to show others. As I edited my recordings, I watched natural strength with a passive mentality. I sent my rate of force development and ground time for the 4-jump to Mike. He showed me his video of 4-jumps, and his numbers blew mine out of the water. I was not even close. My numbers were rather pitiful in comparison.

In his video, I could see that he was violent during the 4-jump. He was in attack mode; it was the same effort you see in a wild animal chasing its prey. Mike’s arms were in sync with his legs, and his legs were stiff like a jackhammer smashing concrete as he jumped with so much force. Mike is three years older than me, too! As I sulked, two feelings hit me in the gut: I was fired up with competitiveness and wanted to beat Mike (with the utmost respect, of course), and I was also filled with motivation.

I thought back to the first time I spoke to Mike—prolonging Father Time was the topic. People like Justin Gatlin, Lebron James, and Allyson Felix are all professional athletes above 30 years of age who are still able to produce at the elite level. Allyson Felix had a child and still competed eight months later. Those “old athletes,” by society’s standards, are pushing forward whether or not fans notice. The evolution of the athlete is now.

I can tell by Mike’s 4-jumps that he believes he can preserve and maximize what’s left in his athletic tank. As my reflection of that conversation came to an end, I expressed gratitude to Mike and committed myself to continue to reach my personal goals as I work out. I will follow suit by having strong intentions.

3. Embedding in Me the Knowledge of Training

I am doing really well as a trainer at DeKalb High School. I give everything I can to both myself and my athletes each year. Different training programs and protocols have given me a better understanding of when to use different approaches with athletes. I have improved and become a better trainer, and I have seen results, whether in the reduction of injuries or in increased athleticism. SimpliFaster has helped me attain these results.

I have improved and become a better trainer, and I have seen results, whether in the reduction of injuries or in increased athleticism. SimpliFaster has helped me attain these results. Share on XAthletes fill up my strength and conditioning classes throughout the day. Teams fill the weight room to maximum capacity after school. The community is getting used to my face, and the coaches are starting to trust me. I seem to be doing well but know that at times I can do better. There are training concepts that I still want to learn so I can teach them to my athletes and coaches so that we, in turn, can all become the best competitors in our respective sports.

People in the industry like Max Schmarzo of Strong by Science and Jake Tuura of Youngstown University convinced me to learn more and to spread knowledge widely. I thought I was giving everything I had to DeKalb High School but actually realized I was nowhere near giving them my full potential. I had so much more I could improve upon and share: programming, learning basic physics for data reading, and more.

I have made connections with the athletes, but I want better for them. No—I want the best for them. I understand that not every high school has a strength and conditioning coach. A lot of coaches do not have one either. This realization has made me want to dig deeper and provide more for everyone.

I am excited knowing that there is no cap on what I can learn. There will always be more for me to learn and teach. This ignites my passion even more and causes me to go to SimpliFaster to read more books, talk to more coaches, and reach out to experts in their fields to continue my personal education.

I started becoming smarter by listening to what my colleagues have to say, by watching what they do, and by recognizing what they have their athletes do and why. The “why” is the most important part of doing something; it shows intent of an action. If intent falters, you learn from it versus just having athletes sweat and do a workout because it seems cool. I must admit I have done that before, but I wanted to drift away from the practice because it’s morally wrong in my eyes. If my expectations are to have athletes train wholeheartedly, then my program and instruction must also be up to par for them and at an elevated standard.

I started becoming smarter by listening to what my colleagues have to say, by watching what they do, and by recognizing what they have their athletes do and why, says @__JoshuaCollins. Share on X4. Sponsoring the Just Fly Performance Podcast

With podcasts being the prevalent go-to for information of personal interest, the Just Fly Performance podcast has been nothing short of essential for me. Host Joel Smith interviews an array of people who have accomplished amazing feats under the strength and conditioning umbrella. I have done case studies from claims by some of his guests, like Keith Barr, Ph.D.; Ebonie Rio, Ph.D.; and many others.

The podcast is great because I can play it through my headphones when I work out and still stimulate my mind with information when I am not able to read. Dr. Keith Barr’s interview about tendon health helped me to understand how tendon tightness is dependent on collagen and that tendon tightness aids in athletic movements. If you’re loading with good nutrition, you will have a high turnover rate and will see the dynamics and functionality of the tendon. I must have listened to that particular interview 50 times. Each time I listen to it, I learn something new, and I am led to research new concepts to try on myself and on the teams that I train.

Hearing theories from the podcast and reading articles about the experiences grew my excitement while challenging me to read. I may not be an athlete anymore, but I use the same competitive qualities to get better at my job. My intention is to level up through training and teaching my classes. I love training athletes and monitoring their adaptations. It has bred a passion to read current research and given me the ability to cite credible sources. SimpliFaster has been a part of that.

As a kid, I despised reading; as an adult, I love it. It is easy to read up on certain topics, and it helps when they are applicable to my job. I’m blessed to be working in a field that I love, and because of that, I have learned to appreciate reading. The podcast is nice and all, but SimpliFaster puts all the content in one hub so that all I have to do is pick a topic of interest to read. The sources are credible because I have read older articles from years ago that are current today. So, for that, I am greatly appreciative of having content in one place that I can rely on for learning.

5. Teaching Me How to Program

Being a student of the game, or in this case, strength and conditioning, has led to other areas in the training paradigm. SimpliFaster publications humbled me. When science can prove that what you’re doing is not as efficient as it should be, something must change. When I began in this field, my programming focused on the exercise and the uniqueness of how it looked. That may be okay for likes on social media, but just because it looks cool does not mean it transfers to athletic development.

SimpliFaster publications humbled me. When science can prove that what you’re doing is not as efficient as it should be, something must change, says @__JoshuaCollins. Share on XThrough reading and listening to others in my field, I have gained an understanding of training concepts and isolated exercises. Training concepts organize training principles into a program that most athletes need and appreciate. Concepts also provide further knowledge on the why and how of movement goals as opposed to just being familiar with how to perform an exercise.

Knowing concepts allows you to determine what exercises to use at a given time. Just knowing an exercise when you work with teams does not determine when you should do it or why. It may look cool, but when you understand concepts, you have the clue to understanding what exercises to use. You can build a program around concepts but not around one exercise movement. As a high school strength and conditioning coach, it is imperative that I program in this conceptual manner to have a better grasp on large groups of different teams.

6. Introducing Technology for Sport

Early in my career, before I became a high school strength and conditioning coach, I was a sports performance coach and I had the opportunity to use the Freelap Timing System. I had heard of it from my frequent visits to SimpliFaster.com and from trying to win a Freelap Timing System on Twitter. As most coaches recognize, the handheld timer is the highest level of technology. Let’s be real, though. A stopwatch is the cream of the crop of timing systems only when it is the only option. It is the “old reliable” way that is not so reliable.

When my place of employment bought four Freelap Timing Systems to train athletes, I was excited to use such elite technology for better accuracy during sprint sessions. It is so simple to use that even someone who is not tech-savvy can learn to use it. It is accurate, and the athletes love it because it is not archaic.

There is something to be said about developing a skill to push a button to start the timer on a stopwatch the moment an athlete moves from a sprint position. I have been around more coaches who missed the button without noticing they were not timing the athlete until the sprint was over. Athletes’ time and energy are then wasted while possibly placing exasperation in their minds because they cannot trust the timing system.

Freelap allows coaches to observe and examine athletes instead of using a handheld stopwatch, says @__JoshuaCollins. Share on XWith the Freelap Timing System, I have never worried about that. There are multiple ways to time someone. Freelap allows coaches to observe and examine athletes instead of using a handheld stopwatch. Athletes can use a start button or sprint through a cone transmitter that connects the analysis of the movement to the free downloadable app. Its simplicity of use makes it a beneficial tool for all parties involved.

I recommend the Freelap Pro Coach BLE 112 to all high school and sports performance coaches. SimpliFaster provided me with the edge I am looking for at this point in my seven-year career. It is a one-stop shop. Whatever you need, the answers always seem to be there.

7. Positively Influencing My Daughter

My last reason for using SimpliFaster is that it has helped me introduce training to my daughter. I was blessed that my daughter developed an interest on her own by watching me train female athletes. There were times when she accompanied me to work, and from the corner of my eye, I watched her mimic movements on her own. Someone once said to me, “Copy the wise and become wise. Keep company with fools, and you will be ruined.” My daughter copied wise movement patterns, and I could not be happier.

I have seen training habits harm kids, especially young ladies who are more susceptible to injuries such as knee ruptures. I am not saying that I am this almighty trainer, but through reading article after article and via the experiences that I have had, I want to make sure that any person who trains with me can transfer force to their sport or wherever they need force to be applied contextually. There are no gimmicks this way. I teach fundamentals and build principles from there. Everything complex derives from basic principles.

As the father of this very active, little 4-year-old girl, it is difficult not to ponder how I would like my daughter to be coached and trained if she decides to participate in sports. Females tend to get the short end of the stick when it comes to sports and force development training. During my tenure in sports performance, I have seen that coaches tend to give up on or show partiality when it comes to women’s sports. In my experience with training female athletes, I may have seen the highest levels of improvement when it came to force development. I had the pleasure of seeing monster numbers in the weight room along with increased athleticism.

My daughter has learned fundamental motor skills like getting into an athletic position, jumping, landing, throwing, sprinting, and more. These motor skills will give her an advantage in functionality and build up her confidence. As parents, we should give youth better opportunities and pass down tools they can use. I view athletic training in that same way.

Being able to teach a 4-year-old has helped me teach those who are older. Once you can understand anything that is newly learned and try to explain its complexities in a simple manner to a child, you find out if you absolutely comprehend it yourself. With all that SimpliFaster has helped me to attain, one of the most important things to me personally is being able to train female athletes and being able to show my daughter that she can train like an athlete.

SimpliFaster Is One of My Guides

SimpliFaster is a comprehensive tool for any coach at any level. To sum up, the lessons SimpliFaster has taught me are that the weight room is a lab, and we as strength and conditioning coaches are the mad scientists. We calculate physical data and control velocity through programming. We are more than motivators; we are more than people making others sweat by doing random movements. We are passionate about the sweet science of force production that gives each and every individual a winning edge to compete at the highest applicable level.

To sum up, the lessons SimpliFaster has taught me are that the weight room is a lab, and we as strength and conditioning coaches are the mad scientists, says @__JoshuaCollins. Share on XThe untrained coach’s eye will miss those things and try to imitate without understanding. SimpliFaster is a staple to give reasoning and to guide coaches to better efficiency. Thus, SimpliFaster will always be my personal go-to for everything under the training sun.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF