Remember when it was cool to insult CrossFit? Admittedly, I was a major perpetrator of crimes against the early incarnation of this fitness phenomenon.

Six or seven years ago, while training in Austin, Texas, for the summer as a mediocre and proud master’s sprinter, I would spot devotees from the CrossFit box down the street, heading to the track at Austin High to crush their WOD. I recall their workout often being a series of rounded-back tire flips, then a dodgy pull-up variation, followed by a few medium-paced 400s run with questionable posture and minimal rest.

Fast-forward to 2016, and CrossFit has come far from simply a military-influenced workout system populated exclusively by devotees who pepper their sentences with “bro” and “elite.”

The CrossFit phenomenon cuts across age and gender, and has adopted a more mature and inclusive philosophy over time. You’ve got to give credit where credit is due: In the general population fitness universe, CrossFit leaders correctly railed against the prevailing 45-minutes-on-the-treadmill-reading-InTouch-magazine crowd. They understood that the intensity of exercise trumps its duration. CrossFit put the “work” back in workout.

Kelly Starrett Emerges as a Posture-Improving, Self-Therapy Advocate

Still, the reality is that every maturing workout philosophy needs a thought leader to move it through early times. For CrossFit, Kelly Starrett emerged as that thought leader. His influence has spread far beyond the CrossFit universe.

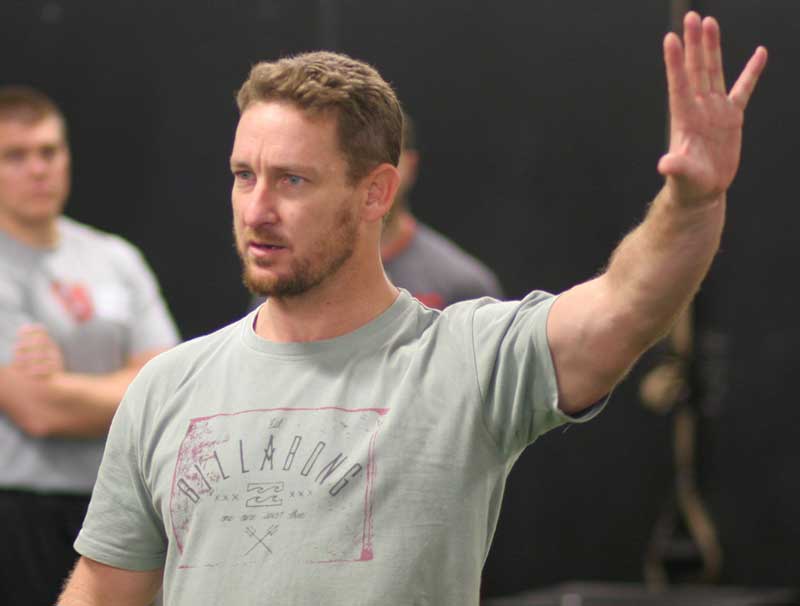

I met Starrett at ALTIS during their apprentice program in November 2014, and his surprise visit was met with respect and more than a little excitement. (Throws coach Nick Scheuerman might have even fanboyed a little.) I remember him calling me out on my crappy tall-guy posture within two minutes of arriving. Kelly Starrett is definitely a straight shooter.

A former member of the U.S. Canoe and Kayak team and a DPT by trade, Starrett is the owner of San Francisco CrossFit, one of the earliest franchises. He has become a one-man posture-improving, self-therapy, advocating machine.

He has written two bestselling books, Becoming a Supple Leopard and Ready to Run, and both are fantastic. In addition to their high quality artwork, they feature sound and incredibly creative approaches to mobility restoration and self-therapy that put control of one’s body firmly back in the hands of the athlete.

Many of the principles contained in Becoming a Supple Leopard were introduced to athletes in our winter Florida training camp last season. The effects were amazing, and literally transformed each athlete’s approach to self-care.

Sitting Is the New Smoking

Starrett’s new book takes his previous ideas a step further. In Deskbound: Standing Up to a Sitting World, he makes a convincing argument that the lowly chair is doing much more damage than the cigarette. In the book, he also asks a very important question: What are your athletes doing the other 23 hours per day when they aren’t training? For many of them, the answer is sitting—for up 14 hours.

In his new book, Starrett convincingly argues that sitting is worse for our health than smoking. Share on XTo combat this epidemic, Starrett creates simple prescriptions that, when followed, aspire to improve virtually any athlete’s postural competence.

I “sat down” with Kelly Starrett via Skype (or, more accurately, he squatted and I sat cross-legged with my core properly braced), and we dove deep into a number of topics surrounding our current “sitting culture.” This was in anticipation of his truly entertaining presentation for World Speed Summit, the upcoming free online speed and power conference.

The Four Key Prescriptions to Counteract Postural Damage Caused by Sitting

We delved into the four key prescriptions of Deskbound, and it was fascinating for me to have a window into the mind of a thought leader in the human performance world.

1. Reduce Optional Sitting in Your Life

When you show up to practice after a night of Netflix ’n chill, it is basically the postural equivalent to showing up to train in jeans and flip-flops.

When athletes treat non-training time as something separate and disconnected from their workouts, Starrett asserts that they are basically showing up totally unprepared to train. “One of the problems is, in that short chunk of training time, we have a lot to get done. We have to warm up and cool down and talk about skills and get you more explosive, improve your athleticism, and redress your dysfunction.” Reducing optional sitting and holding the athlete accountable for their posture in everyday life allows them to train at a higher level.

2. For Every 30 Minutes You Are Deskbound, Move for Two Minutes

If you happen to be in a situation where you’re forced to sit, make a conscious decision to move. In spite of all of the best efforts of some very influential people, “we have not budged the childhood obesity epidemic.” There is still a huge problem with caloric intake and the quality of food, but what is also clear is that kids are moving much less than in past generations.

While places like Oregon have compensated by increasing the amount of physical education in schools, Starrett argues that the exact same caloric burn could be achieved passively by simply changing the type of desks in classrooms. Starrett asserts, “You can meet all [those] activity goals with a standing desk.” Early evidence suggests a 25-30% increase in daily calorie burn when students work from a standing base.

3. Optimize Position and Mechanics Whenever You Can

People ignore the fact that posture is a skill that needs to be practiced. “Posture is just a Latin word for position. Can you imagine bragging about bad position, or bad biomechanics?” asks Starrett.

“Across socioeconomic groups, kids 8-18 are spending up to 7 1/2 hours per day on [a] screen. We’re making the physiology match the technology instead of having the technology match the physiology.” Athletes need to actively resist this march in the wrong direction.

4. Perform 10 to 15 Minutes of Daily Maintenance on Your Body

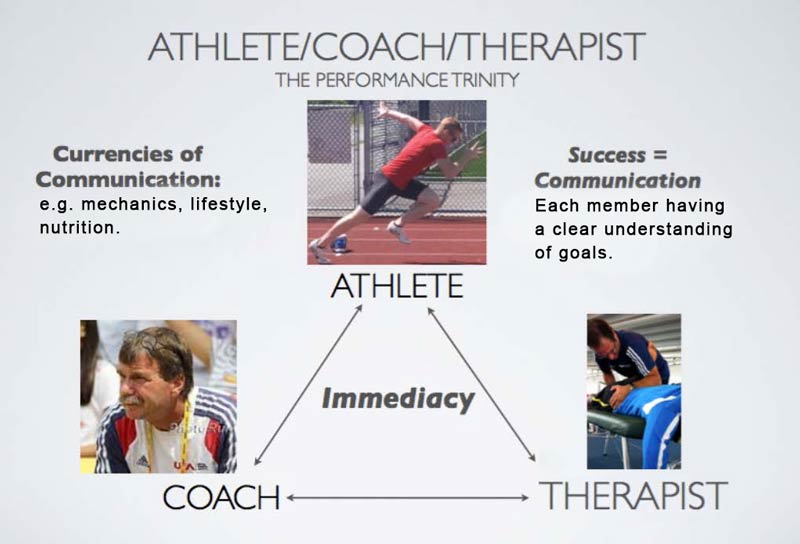

Over time, therapy has somehow become something that people think only a therapist can do. According to Starrett: “Dan Pfaff has been such an important piece of this conversation. Take the unskilled care and move it beyond the paywall of for-profit medicine. In the past 20 years, we’ve put it all on the other side and divorced it from the strength and conditioning process.” Athletes should be able to manage their own muscle tone, and a corresponding increase in mindfulness around their body status will be the norm, not the exception.

Watch Starrett’s Online Presentation at the World Speed Summit Next Week

There is, of course, far more to Kelly Starrett’s Deskbound than the four core principles above, and his World Speed Summit presentation delves into a variety of areas that are deeply connected to the training of speed athletes. There are a number of great takeaways—including a simple yet ingenious way of using the very controversial Training Mask!

Spending an hour listening to Starrett present allows a window into the mind of one of the most influential thinkers in human performance today. In addition to Starrett, they’ll be presentations from more than a dozen other experts. I hope you check it out: The World Speed Summit is FREE to watch at this link starting June 27th.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF