If you have been in the strength and conditioning profession for at least a minute, you’ve most likely heard arguments for and against Cleans, Hang Power Cleans, and other Olympic weightlifting movements and their derivatives. You will hear how good they are for Rate of Force Development, how good they are at helping athletes receive force, and how fun they are to teach and perform. Equally, however, you will also hear how they are hard to teach, dangerous, and not as effective as loaded jumps.

So….pick your side of the fence.

Additionally, if you scroll S&C social media for 45 seconds, you will most likely see at least a dozen videos of Olympic lifting being done—some good reps and some bad ones. But whether it is a CrossFit athlete, an Olympian, or a high-school football team, everyone is doing cleans and showing off their stuff. People know the benefits, how the lifts correlate well to sprinting speed, skating speed, and jump performance. Everyone loves them, everyone seems to do them, and sometimes my athletes do as well (which, then, probably has you confused as to the title of this article).

Do No Harm: Limiting Factors with Oly Lifts

Our Men’s and Women’s Volleyball athletes do a heavy dose of Olympic weightlifting movements all year long. They love it and do the lifts very well. I’ve actually written an article on how I program our Olympic movements with our “Rep-Drop Method” (you can read that article here).

I’ve also started using that method with our Track & Field groups, with a lot of success over this past season. BUT…almost no other team I coach does them. Now, with so many benefits that I would want our athletes to have (RFD, speed, power, etc.) why not just get everyone to Olympic lift? (Especially considering that I was a competitive Olympic weightlifter for 5 years, so I know all the movements and how to coach them.)

My opinion is simple—I just don’t think the juice is worth the squeeze for most of our in-season athletes. You see, Olympic lifts—cleans in particular—require a high level of mobility, technique, and power to execute well and get a benefit. Many of the athletes we see simply do not have the requisite mobility to be able to perform these movements safely. Whether it is from previous wrist injuries or having long forearms, they are just not able to get into the “catch” position for a clean safely.

But, for whatever reason, we have found that almost all of our volleyball players and a large majority of track athletes can get into the positions we need. Could be because volleyball needs really good shoulder and t-spine mobility, so they have that inherently to make them good at their sport? Could be that track doesn’t use their arms as much, so they haven’t been damaged from contact or bracing falls? Honestly, I am not totally sure the reasons, but it is a trend I have seen in our athlete population.

Olympic lifts require a high level of mobility, technique, and power to execute well and get a benefit. Athletes we see simply do not have the requisite mobility to be able to perform these movements safely, says @chergott94. Share on XIn the past, I’ve done tons of mobility drills and stretches, trying to get my athletes into these positions safely—but nothing seemed to work. Then, after examining their anthropometrics (limb lengths), I realized that those who have long forearms simply can’t get into the right position without the bar crushing their windpipe. While my examination works, I should have seen it earlier when I saw these same athletes doing Front Squats in a cross-arm pattern, not a front rack. After all, if you can’t hold a front rack in a squat, chances are you won’t be able to get into it in the blink of an eye to catch the bar in a clean.

Another issue stemming from this lack of mobility is the higher injury risk that comes with it. Whenever you try and fit a square peg into a round hole (i.e., force someone to catch a clean when they don’t have the movement pattern locked in), that greatly increases the risk of something going haywire and busting down the chain, like a wrist or shoulder. My number one job with my athletes is “Do no harm.” For most of our kids, I can get them to do a well-executed squat plus some jumps and sprints to cover what we need—such as rate of force development, fast-twitch muscle fiber usage, and force production in multiple planes of motion—with even less risk of injury.

If you can’t hold a front rack in a squat, chances are you won’t be able to get into it in the blink of an eye to catch the bar in a clean, says @chergott94. Share on XSprint, Jump, Throw

Now, many of you might be thinking why not just teach them how to do the lifts over the summer or off-season so they can do them in-season. Agreed. 100%. But the issue with our setting (and many university settings, especially in Canada) is that our kids go home for the summer—meaning, I would be programming cleans for them to try on their own in some big box gym somewhere and hoping that goes well. Yeah, not a great idea.

Which leads me to my latest craze in programming and the main point of this article: Sprint, Jump, Throw.

I know that didn’t just introduce you to any new concepts and this is something you are all doing in some capacity—but over the last year, these simple tools are something I’ve really doubled down on. Knowing that I needed to enhance the transfer of our weight room work, I started to play around with different set and rep schemes, as well as different exercises. Nothing was having the effect I wanted. Why not? Because sport isn’t squatting. It isn’t benching. It isn’t 3×5 or 2×10. It’s sprinting. It’s jumping. It’s throwing (or shooting).

So why not train those more?

Over the last year, I’ve decided to ramp up my focus in those areas. Whereas before I would maybe have sprint exercises 1-2x p/week, a couple jumps and maybe a throwing movement as well, for most of our teams I now program all three each day. We do a sprint, a jump, and a throw each session (2-4x p/week). This gives our athletes exposure to high velocity movements along with the higher force weight training we still do (surfing the force-velocity curve). I believe this approach greatly enhances the transfer of our sessions by getting the athletes to apply their strength and power in movements they actually need to perform in their sport (again, sprints, jumps, and throws).

We do a sprint, a jump, and a throw each session (2-4x p/week). This gives our athletes exposure to high velocity movements along with the higher force weight training we still do, says @chergott94. Share on XI do have some general classification systems for each of these, just to keep them sorted in my head. I’ve stolen a bunch of ideas from great people like Matt McInnes-Watson and his tier system for plyos, but basically this is how I structure things:

Sprints

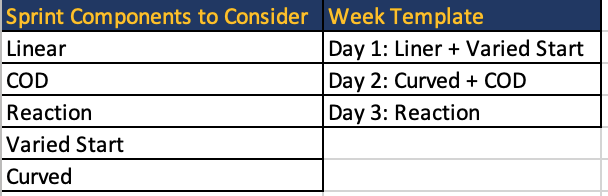

In a 3-day program, we will sprint each day right after our warm-up. We do this in our gymnasium, which is adjacent to our weight room, or outdoors (weather permitting). Day One is linear, but with a varied start so they get used to putting themselves in the right sprint position from different start positions. Sports are weird and have you in all sorts of positions, so I want our athletes to be able to “go” from anywhere their sport asks of them. These starts include starting on one knee, starting on your belly, or starts facing the opposite direction of the finish line. Day Two will have a change of direction component in the sprint: could be a simple 45 degree cut, a stop and comeback sprint, or a curved sprint.

Image 1. Reaction Balls.

My goal is to expose the athletes to speeds at various angles that sport demands and make sure they have the necessary movement capability—additionally, I want to expose their feet, ankles, knees, and hips to those game-relevant angles and forces (I steal lots of stuff from the 8-Vector System on this day). For our Day Three speed work, I’ve started to incorporate a reaction component. This includes tennis ball drops, sprinting on a “go” call, or actually using Reaction Balls (see image above). This day involves—by far—the most effort…and is also the most fun. This way, we get linear speed, change of direction, varied starts, and reaction work (plus effort and smiles) all in a single week of work, each and every week.

Figure 1: Sprint program ideas.

Jumps

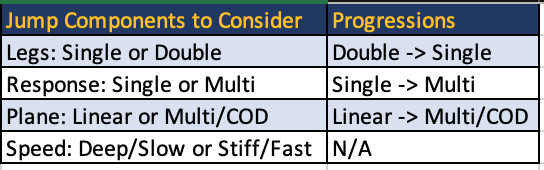

I won’t go into a deep dive into other people’s work here (i.e., Matt McInnes-Watson), as that is way beyond my brain power. But for me I try to categorize jumps into:

- Single Leg or Double Leg

- Single Effort (i.e., one broad Jump) or multi-response (i.e., double broad jump)

- Linear or Change of Direction (jumping in a straight line or jumping back and forth/in various directions)

-

Deep Tier/Slower or Stiff/Springy/Fast

- Deep Tier—Staying low and bouncing in and out of a low position (like the bottom half of a squat and pulsing up and down).

- Stiff—Staying tall and trying to have minimal knee/hip bend on each rep.

Within that, you could have a broad jump (double leg, single effort, deep) OR a single leg zig zag pogo (single leg, multi-response, change of direction, stiff). Lots of variety, lots of progressions, lots of fun. To give you a brief insight into our progression model, I always start our athletes with something that is the least complex, like a double leg pogo on a spot. Then, we progress throughout the season in one area. For example, we might move from double leg to single leg, or double leg but then we are moving laterally. Then, we just layer on top one area of complexity at a time as the athletes master the movement and get better at it. There is no sense rushing through progressions if they can’t do the previous ones well.

Figure 2. Jump programming ideas.

Throws

I don’t have as formal of a template for throws. I just try to get some rotation work like rotational tosses, some horizontal work (chest pass), and some vertical work (slams). I will play around with the foot positioning to get a varied effect, but these have the least structure to how I program them. Just grab a ball and let out some frustration!

Some of my favorites are:

- Med Ball Chest (horizontal upper body power).

- Med Ball Slam (vertical upper body power).

- Rotational Throw (rotational power).

[vimeo 1088826918 w=”800″]

Video 1. Med Ball Slams—cue for max intent, “break the floor.”

From these, we can then change up the leg position: for example, from two feet under hips to a staggered stance to taking a step into the throw as the athletes get more competent and are able to master the upper body movement coupled with leg action (which better mimics the coordination demands of sports). I always cue athletes to “break the wall/floor” as the only goal with throws/slams is to move balls as fast as possible. I recommend they use a med ball that feels sort of heavy, but they are still able to move it really fast. Always err on the side of too light rather than too heavy for this.

I always cue athletes to break the wall/floor as the goal with throws & slams is to move the balls as fast as possible. I recommend they use a med ball that feels sort of heavy, but they are still able move it really fast, says… Share on XWhile these med ball throws are pretty general, this system keeps it simple while making sure we aren’t just training the same thing over and over. Plus, over the last year this approach has yielded a ton of positive benefits, including:

- Better testing numbers.

- Reduction in injuries.

- A more positive reception of the programs overall.

Gone are the days of athletes asking “Can we do more plyo or speed work in our lift?”—because now they now get a heavier dose of these every time they walk in.

The last and biggest benefit from doing more Sprint, Jump, Throw work in place of Olympic lifts is that it doesn’t take 1-2 weeks to learn the movement, get better at it, get stronger, and then add some weight to get an actual benefit from it, like first time Olympic lifters do. The athletes can get a benefit immediately from sprinting, jumping, and throwing as it is all stuff they know how to do (and can do better than I can demo most of the time too).

Choosing the Right Exercise for the Right Result

While Olympic lifting is a fine way to get faster, gain explosiveness, and learn to receive force, I can get the same adaptation from a method that is simpler and easier to learn. Which, at the end of the day, is what my job is—deliver results/get adaptations. It doesn’t matter what exercise I use, I just need to deliver the goods. Again, this doesn’t mean we don’t clean or snatch, but just that over the last year I’ve shifted away from them more and more, as I have had success with the Sprint, Jump, Throw approach.

While Olympic lifting is a fine way to get faster, gain explosiveness, and learn to receive force, I can get the same adaptation from a method that is simpler and easier to learn., says @chergott94. Share on XSo, if you use cleans and I use sprints, jumps, and throws and both of use get our athletes better…then who cares? As much as I love a good online debate, to me, as long as you are doing your best to serve the people you work with and get them results, you are doing your job. So use cleans, or don’t. Just make your athletes better.

Peace. Gains.