There are countless ways to perform movements, many philosophies that make sense, and innumerable methods of programming, so it would be absurd to claim that my way is the only way. I often stumble across something online that differs considerably with an approach of mine but doesn’t necessarily contradict it. There are, however, a lot of practices or opinions that I feel could use some help and a short list of concepts or setups that I feel are simply wrong or misunderstood.

Based simply on my own experience and a long time trying to rationalize certain craziness, this article contains 21 tips to potentially help change the way people view certain concepts or techniques. The idea came to me recently when a memory popped up on some social media platform of me and Jeremy Frisch authoring an article for T-Nation about 14 years ago titled “50 Tips for Serious Athletes.” It was a pretty fun and simple article that got a lot of love. I think people appreciate concise actionable tips that they can implement at the drop of a hat, and I hope to do the original some justice.

It’s never a bad time to challenge your own beliefs, says @ExceedSPF. Share on XI categorize the list into three parts. First are simple setup, organization, and technique missteps. From equipment setups to body positions, there are a few repeat offenders that I want to discuss first. Second, I highlight thought-process or concept-related elements. Occasionally, I’ll read something that changes my view on a topic, while at other times practical experience wins out, but it’s never a bad time to challenge your own beliefs. Last, I lay out some programming and training plan considerations that may or may not get me assassinated by the Armchair Warrior’s Guild.

First up…

Common Setup Flaws, Organizational Ideas, and Technique Errors

1. Lasers: Type, Setup, and Data Collection

The first issue I see fairly often is not placing the start laser in the correct place. There are a few potential “correct” ways to time sprints. Most “dash” timing involves first movement starts or off a “gun,” but none, in my opinion, should allow large magnitude displacement before the clock starts.

This is exactly what “two-point, front foot laser starts” result in, and it’s why that method is completely inaccurate. Obvious to many, by the time the front foot lifts and the laser is tripped, the athlete has established well over 1 yard of displacement and gained that much more momentum. Using this method, it’s not uncommon to see 10-yard times in the 1.2’s for faster athletes. That time should trigger a warning, and anyone understanding speed would step back and consider the issue at hand.

The first movement must start the clock. If for some reason you must only time two-point stance sprints, try setting up the laser on the back foot. It definitely creates more of a logistics nightmare having to move it for each individual stance, but at least you’re approaching what is standard. In almost all sprint timing, the clock starts on first movement. Be safe and use a three-point front hand laser position.

The second is laser height on subsequent gates. Mid-shin or knee-high beams don’t make much sense to me at all. Universally timed near the hip or waist, it’s almost certainly inaccurate to time a sprint with the shin or knee. The shin will be ahead of the hip by however long your femur is.

Lastly, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the double-beam versus single-beam argument. Single-beam lasers fail in terms of accuracy. Anything that trips the laser will stop the clock. An arm or hand, knee or rogue bird could maybe stop the timer. A double-beam laser will differentiate between an early trip when a second trip (arm then torso) is in close proximity. Whenever possible, go with a double beam.

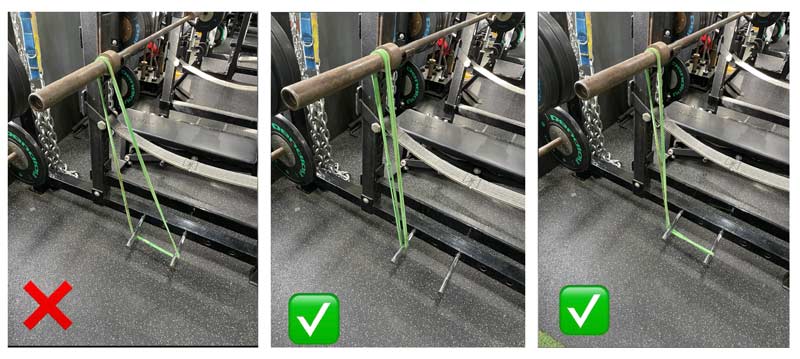

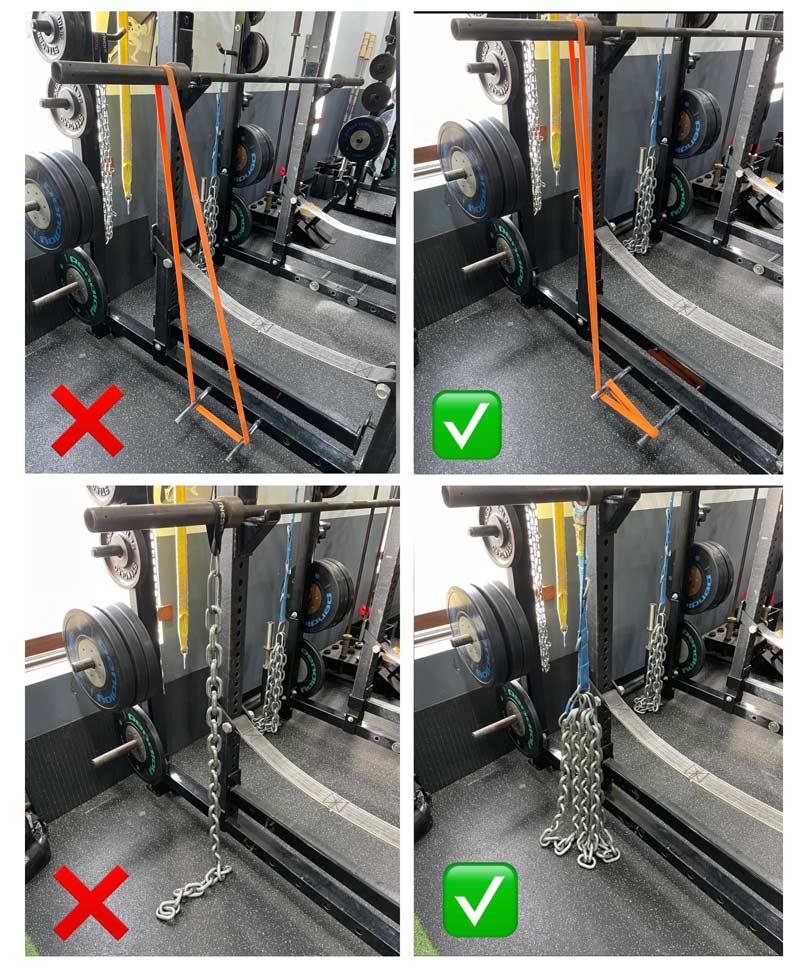

2. Bands & Chains: Height, Tension, and Repeatability

I’ve seen a lot of band setups that leave much to be desired. I don’t want 12 pounds of variable resistance. The strength curve for any athlete using this tool should require a much larger gap between the top and bottom of the movement. That’s why setting up your bands to have adequate tension at both end ranges is important.

Chains are the same. One long chain attached to the bar sleeve will provide very little variance in the load. At the top there might be 40 pounds of added chains and at the bottom 28 pounds. That is barely variable resistance if you’re squatting any appreciable load. Use a chain loader to get enough weight to create a significant increase in load and earn the nomenclature of variable or accommodating resistance.

3. Push-Up: Scap Movement > Humeral Movement

Moving mainly through the humerus (flexion/extension) rather than scapular retraction during a push-up is a mistake I see most athletes making when they first step into the gym. Somewhere along the line they learned this pattern. Since the “closer elbow” trend started, people took this to the extreme and brought their elbows all the way to their ribs. This position doesn’t allow the scapula to move on the ribs, and all you’re left with is extension of the humerus.

The eye test alone should deter this erroneous pattern. I suggest about 45 degrees of abduction (give or take) to allow retraction, which will aid in shoulder health and provide a better overall pushing position.

4. Utilize Wall Space to Save Time and Help Instruct

The use of conversion charts, information posters, and wall templates is a surefire way to increase efficiency in your training space. I wrote an entire article on this topic, so I’ll save time and space and just link to it here.

5. Bench Press Setup Is More Than Just Hand Width

Every exercise has a novella’s worth of cues, tips, and instructions that will make or break the lift. There are tons of setups, foot positions, hand positions, and so on that are semantics across different individuals, but there are a few basic tips that can drastically improve a bench press’s functionality, safety, and execution that I don’t see in the “athletic” population. Most powerlifters have all of these down, and I’m sure they would roll their eyes at this post, but many people in collegiate, high school, and private S&C facilities are missing a chunk of these tips that I will list below.

There are a few basic tips that can drastically improve a bench press’s functionality, safety, and execution that I don’t see in the “athletic” population, says @ExceedSPF. Share on X

-

- Hand width: Unless you are doing a special grip, I suggest finding a grip that gives you the best leverage over the bar. Most of the time, I like the fist to be above the elbows at the bottom of the press and the forearms mainly perpendicular to the floor. As a side note, the name “close grip” should be changed to “closer grip.” A slightly narrower grip is enough to create the change in emphasis and not enough to wreak havoc on the wrists and elbows.

-

- Scap position: The scapula should be retracted and typically depressed quite a bit. The idea is to pin the scap to the bench and get the shoulders in a stable position using your upper back and lats.

-

- Back arch: Yes, you should arch. How much you should arch depends on quite a few variables, but lying flat puts your shoulders in a disadvantageous position, requires more range of motion and extension of the humerus, and ruins the bar path for optimal pressing.

-

- Foot position: There are debates and rule differences regarding heels flat or not, but your feet should be closer to your head than your knees. Get them far enough back to be able to press your feet into the ground, create tension through your hips and legs, and not allow your butt to lift during the concentric portion. This is tricky for people at first, but the worst thing you can do is allow your feet to be soft on the ground and in front of your knees (feet should not be farther from your head than your knees).

-

- Eccentric: I like to cue an active pulling during the eccentric portion, rather than simply passively allowing the bar to fall. Keep lats on, guiding your elbows down (not out) and the bar just below the sternum.

- Concentric: Think about pushing yourself through the bench. The cue “drive the bar up and slightly toward the rack” works best for most people.

Whether or not you use any or all of those suggestions, I think focusing on the scap and foot positions could be an instant game changer for most people.

Thought Process and Concepts

6. Range of Motion Is Not the End-All, Be-All

This is the first of three controversial range of motion points I will make in this section. Yes, when you have control over a range of motion, by all means, train it. The more and more I watch people squat and hinge, the less I am concerned with the arbitrary standard “full range.” Depending on body proportions, bone structures, injury history, and a slew of other factors, sometimes depth is unattainable. The options are to train around it or get the ROM through ill-advised mandates. Excluding powerlifters, where squat depth is not a suggestion but a mandatory marker for a successful lift, I don’t care if an athlete can do a full ass-to-grass squat with load. I care that they use the range of motion they currently possess.

I don’t care if an athlete can do a full ass-to-grass squat with load. I care that they use the range of motion they currently possess, says @ExceedSPF. Share on X7. Use Technology to Determine Appropriate Range of Motion

My second point will elaborate on the previous point. Barbell tracking technology—for example, GymAware or Vmaxpro—can provide you with an objective range of motion as you use your eye to verbally cue the pattern. For example, have your athlete squat with moderate weight to a comfortable depth, for you and the athlete, where they have control over their spine and maintain a good position. The technology will display the range of motion, and the remaining sets can be compared to the initial/optimal findings.

8. Stop Demonizing the Partial Squat…or Partial Anything

My final point on range of motion seems to really bother people. We use partial squats. We do partial speed squats and partial maximal or supramaximal squats as well. I will stick to a single exercise—in this case, the squat, for brevity’s sake—but we use partial movements in a number of exercises.

Tell me why the RDL (single or double leg) and trap bar deadlift, both partial range of motion exercises, are beloved by many while the partial squat is vilified and demonized by the masses. Even the Bulgarian split squat is often done with less range of motion than a true 90-degree squat.

Watch sporting movements, jumps, sprints, and everything else on the field, court, or ice. They are often done in a partial range of motion demanding high magnitudes of force or velocity. Why would we not want to emphasize this in training from time to time? In fact, we find partial speed squats and partial heavy squats translate just as well, if not better, to sprint and jump performances when compared to the traditional “full range of motion.”

The one argument I can understand is for injury prevention or tissue integrity at end ranges. This doesn’t affect my opinion, however, as we train full ranges of motion in a multitude of other movements more suitable for pushing the end range a bit more.

9. Use Technology to Verify a Program’s Efficacy…or Lack Thereof

Jump mats, force plates, timing lasers, barbell tracking tech—whatever you can get your hands on can be an effective way of keeping you honest. I hope everyone believes in their programs, but how many people test them? Using 1RM testing can provide some context but often that is just a small piece of the puzzle.

![]()

When dealing with generalists (anyone not competing in weightlifting or powerlifting), the important stuff is how the strength work applies to the sport. I still believe getting stronger should be a priority for most programs; however, speed, power, endurance, and a few hundred other qualities might be of more value than a 1RM bench test for a soccer player.

10. Progressions: Not Just for Lifts

Conditioning could be the most overgeneralized term in the industry but having the ability to repeat efforts for an entire game can separate the good from the great. Designing effective, challenging, and progressive energy system programs is the key.

The design shouldn’t be to crush everyone and let them slowly get more tolerant of the same dose over an extended time. That’s not how you design strength programs, and it’s not how you should design conditioning either. For example, two 300-yard shuttles are brutal on Day 1 of the off-season but on the easier side come the end.

For years, we have utilized a progressive system for all of our energy system development and testing protocols. We start out using shorter duration running with similar work:rest ratios and slowly progress the work distances, maintaining a very similar total distance and work:rest ratio. We do this with shuttles, longer tests (2-mile, Cooper), and general conditioning, like cardiac power intervals or aerobic density work on the bike, as well.

We’ve created a few templates that allow the athlete to visualize each phase of the program and see how it progresses and where they are at any given point in the off-season.

11. Stop Teaching Everyone to Land Soft

As with most “rules” or concepts, there are exceptions. Teaching certain people (young, old, novice, injured, early off-season) how to land soft and absorb force quietly can be of use. However, sport is not soft, and it’s not quiet—it’s filled with violent collisions both body-to-body and body-to-ground, and if you constantly do light and quiet single leg hops over 6-inch hurdles, you do your athletes a disservice when it comes time to cut and sprint in the game.

Box jumps and low-amplitude hopping has its place. But incorporating pogo jumps, drop jumps, multi-rebound jumps, weighted jumps, Russian and Polish plyos focusing on stiffness, and many other exercises will turn your athletes into better performing mutants come game day.

12. Body Weight Is Not Enough

Certain patterns are categorized as “body weight only.” To me, that misses a huge opportunity. You can manipulate single-leg squats, push-ups, glute extensions, and more exactly like any other lift. Strong people can add considerable load in any of the previously mentioned movements to target better adaptation.

If strength is the goal, 20 push-ups might be far from appropriate. Try adding some considerable weight to your back and pushing in the 5-8 rep range occasionally. Many athletes despise single-leg squats. If you prescribe eight reps, many will stop at eight reps regardless of how many reps they have in reserve. Encouraging the use of additional load to make the prescription challenging is the only thing that makes sense. And for people who use 5- to 10-pound plates in their hands…yes, that counts, but we all know that actually makes them easier due to the counterweight.

13. The Bulgarian Split Squat Has Its Own Risk/Reward to Consider… (*cough* and It’s Not Single-Leg)

We use Bulgarian split squats all the time. It’s just not a true single-leg movement pattern. If you’ve ever done them with considerable weight, you’d probably agree. My real argument here is that they do not magically eliminate all risk just because of less axial loading. Asymmetrical loading on the pelvis can play an integral role in changing the position of the spine. The rear foot height can alter the pelvis and hip significantly as well. The stride length can put more weight either on the front leg or the back hip and even the front foot position can stress the knee, hip, or back, depending on its position.

My real argument here is that Bulgarian split squats do not magically eliminate all risk just because of less axial loading, says @ExceedSPF. Share on XNext time someone tells you no one should squat, ask them to consider the implications of other movements before they spout off claims from the heavens.

14. It’s Called Velocity-Based Training, Not Max-Velocity Training

The response “Well, if we want to train velocity, we’ll just sprint, cause it’s faster than lifting” is just a strange way of saying you don’t understand VBT in the slightest. My contention is that its efficacy is only ever diminished to save the objector from having to purchase the tools to experience VBT.

Velocity-based training is decision-making. It’s goal or target setting, and it’s highly effective. If you want outcome X, stay in velocity range Y. Maximal efforts with mean velocity .19 m/s will by no means elicit the same adaptation and response as multiple sets of .79 m/s. When we have a tool as simple as some of the VBT systems are, it seems crazy not to use them.

Besides the more accurate targeting of motor abilities, giving athletes visual and objective feedback on their effort is invaluable. Hook up a transducer to a bar and have an athlete squat or jump or bench or whatever. I guarantee a noticeable change in the effort displayed from set 1. Cost aside, if you can get your hands on a VBT system, experiment and look into the actual application a bit before using the excuse I mentioned above.

When we have a tool as simple as some of the VBT systems are, it seems crazy not to use them, says @ExceedSPF. Share on XProgramming Errors and Considerations

15. Pairing Everything and Anything

I’m just not a fan of pairing main movements that are not intended to potentiate or benefit one another. I understand time restraints can play a huge role in how college strength coaches program and lay out their lifts, but when time is less of a concern, let rest aid in the efforts.

Main lifts don’t need an ab and mobility exercise paired with them, especially if there is any cross-contamination, so to speak. I don’t want my upper back and core fatigued going into a heavy front squat. To me, this adds unnecessary risk all in the name of squeezing things in.

16. Pairing Considerations: More Than the Agonist

To expound a little on my previous point regarding pairing movements, I will discuss four items I think should get more consideration when pairing.

- The first is grip-intensive pairing. Grip is a determining factor in many lifts. Yet many programs disregard it, at least in terms of considering its overuse. Let me explain through a hypothetical.It wouldn’t be uncommon to see a Bulgarian split squat using DBs at the side on a number of programs across many facilities and institutions. Some of those programs will undoubtedly be total body lifts and many might include chin-ups, RDLs, cleans, and/or rows. Most of those seem to be fairly different categorically. However, imagine completing 80-100 reps of those previously mentioned exercises and having to hold a pair of dumbbells. At the very least, you’ll be more inclined to grab a lighter weight, otherwise you might have trouble holding your steering wheel on the drive home. The agonists or main point of the lifts all differ greatly, but what might go unnoticed is how much demand they put on the hands and forearms.

- My second pairing no-no is brief but important to mention: core-involved overlap. Not every lift involves a high degree of core stability, so using low-taxing movements when pairing with high-taxing movements can benefit the athlete greatly. A quick example is pairing core patterns with push-ups, mostly seen in circuit-style programming. Maybe using supine or standing triceps patterns would be more beneficial when pairing with a challenging core pattern. My next point will involve the core pairing a bit more but from a slightly different position—pun intended.

- Third are positional-redundancy pairing issues. When pairing two seemingly unrelated movements, you should consider what they will require. For example, hamstring + rowing patterns. We already discussed grip and core, so let’s tie those into this point as well.The Nordic hamstring curl has no grip but a lot of core requirements. What row can we pair with it? The bent-over row has core, grip, and hamstring involvement, so maybe that’s a bad choice. Maybe inverted row is another bad choice because if you’ve ever tried to hold a bridge in the inverted row right after a challenging set of hamstring work, you might recall the cramp/fatigue that can pop up after a couple sets. My argument is that a chest-supported DB row might be the perfect complement to Nordic hamstring curls, and while the agonist mid/upper back was the only target for your program, the outside factors could make or break how it is applied.

- Last is more of a generalization on biomotor abilities pairing. At certain times, it’s important to just get a bunch of stuff done. Other times in the most conjugate of conjugate programs, everything is all mixed in and it works. But I would argue that having more biomotor ability-focused programs can be very beneficial in how your athletes adapt.I think most people tend to agree that pairing like qualities—speed and power, for example—complement each other a lot better than, say, speed and glycolytic work. That’s why you will often see separate sessions for acceleration and lactic work, but it is much more common to see poorly paired lifting plans. I’m not sure why it’s not looked at in the same manner.

If you are on a mainly “power” focused strength day, exercise selection may include Olympic work, speed/heavy squats, throws, sprints, and jumps. They all seem to coexist well, and might all be perfectly laid out, but if your rep ranges are going from 3’s to 20’s and in a circuit-style complex, I doubt you’ll achieve the desired effect. In summary, although power cleans are considered “explosive” or “power” exercises, nothing done for 15 reps per set is considered “power.”

The overall theme here is to consider the goal, take in non-agonist considerations, and remind yourself of the main objective for each lift and the lift as a whole before choosing exercises arbitrarily based on their globally intended use.

17. Believe It or Not, the Goblet Position Isn’t Always Best

I probably could have squeezed this in the previous point regarding pairing, but sometimes front loading someone in the goblet position isn’t the best approach. Yes, it is often a good choice for beginners to teach organizing themselves under a small load, but it has its own limitations. Spine flexion intolerance, anterior shoulder concerns, pairing with pressing patterns, and anterior-dominant young athletes are just a few of the reasons it could possibly be a poor choice for any athlete.

In terms of more advanced athletes, the position itself is somewhat problematic for a heavy loading option. It is not the same as the “front squat” position, and although it doesn’t axially load the spine the same, it most certainly brings along some shearing forces and flexion concerns because of the arm and upper back position. You can’t extend the thoracic spine well when your elbows are down and together. It’s just not manageable. So, although biasing toward a flexed thoracic spine won’t kill anyone, it could very well aggravate some people.

At some point you have to consider the following: Am I more concerned with challenging my athlete’s position and arms, or am I trying to develop leg strength and power, says @ExceedSPF. Share on XAnd, at the very least, holding a 200-pound DB like a goblet is absurdly challenging for a lot of people. But how many strong people have trouble squatting 200 pounds? The answer is not many. At some point you have to consider the following: Am I more concerned with challenging my athlete’s position and arms, or am I trying to develop leg strength and power?

18. Cookie Cutter Programming Can Be Eliminated with a Little Planning

Giving everyone on the team the same program might be the only option for some coaches. Limited space, low coach-to-athlete ratios, and a host of other issues make it challenging to individualize, but planning eliminates this challenge. Take some time to create some templates that consider movement restrictions, equipment sharing limitations, athlete ability differences, and needs analysis considerations, and even consider the different training schedules across athletes and across seasons. Ability/genetic makeup and schedule considerations are the two main factors we consider regarding program differences in our population.

A lot of our athletes, more now than ever, have to do a jump/force/velocity type of assessment to get the program that fits best with their needs. It doesn’t mean their whole plan is different than their teammate’s, but maybe the emphasis on some patterns will differ slightly. We designed a quadrant system to categorize these athletes, and although it takes me a little more time programming, these programs have worked better, and we will use them later for other athletes. Improving the product and the athlete are primary objectives.

My suggestion for coaches with lots of constraints would be to slowly lay out your template system, figure out how to assess and categorize as efficiently as possible, and then work in the nuances slowly over time. For example, your average high school football team might have 5-6 freaks who jump through the roof and 5-6 kids who are all kinds of destroyed. Maybe you have three programs: Regular, Freaks, and Wrecked. (Just don’t label the plans that way, as you might get some backlash.)

Schedule tendencies, mainly infrequency, is one of the biggest factors for us in terms of programming and how we lay out our field work and programming. Many of our athletes train 4-6 days per week, and this is the easy stuff. With 4-6 days, you have enough time and space to include a lot of movement patterns and target a few biomotor abilities. There are a decent number of clients who can only train 2-3 days per week and seem to be consistent on which days those are. This makes sense, because they are most likely bound by other obligations.

We have designed many different options for our strength programming, and we have changed up how we lay out our warm-up, preparation, and field work to account for this. We rotate through our warm-up protocols incongruently to the days of the week, so that people get enough consistency to learn and improve and enough variation to “touch it all” (so to speak), and we won’t do the same thing every Monday and Wednesday if they are consistent on their training days.

We do something similar with field work. We may keep Monday as an acceleration day and just change up the focus (heavy resisted accels, longer accels or RSA work, start-based technique), or we might rotate what category we do on Monday altogether and do a deceleration session on alternate weeks. Regardless of what we are doing, by mid-week we start to separate athletes into “what have you done this week” groups. From Wednesday through Saturday, we might have a couple different things going on during the field work. First day-ers might be doing starts while Third day-ers might be on a regen tempo day.

However we lay it out, we always try to consider the athletes and be flexible. The worst offender is the inflexible private facility. The one that only does X on Monday and Y on Tuesday and so on. It’s very likely you will have kids who never show up on Monday because of schedule issues…do they just never train the X variable?

Make some templates to allow for subtle nuances to improve your product and your athletes’ experiences and results.

19. Demographical Nuances: Age, Training Age, Sex/Gender

All of these nuances are simple to grasp. People who have less time under their training belt, less testosterone, and/or less strength and muscle can afford to use shorter rests and shorter overall lifting sessions. A very strong college athlete might take eight sets just to reach their first working set, whereas a younger novice athlete might get four sets of the same exercise done in six minutes. The general rules for rest do not apply because the loads are proportional but not high enough, in absolute terms, to require the same amount of time and preparation. An elite athlete might spend 3-4 hours total in a training session. If your 12-year-old is spending more than 60-90 minutes in the weight room, you are missing the boat.

20. Give More Freedom on the Least Important Stuff

Some will argue that biceps curls and ab work are vital to any good beach season or upcoming game. Look good, feel good. However, I am slightly less concerned with the volumes, rests, and exercise choices here than with the big stuff. Allow athletes who have some time with you to make choices on their “extra work.”

Allow athletes who have some time with you to make choices on their “extra work,” says @ExceedSPF. Share on XWe use “extra work” or “fun & guns” constantly. It makes for a better environment and gives the kids a little say in what they do. Sometimes we give a little more direction like “anterior core choice,” and sometimes we leave it completely open for interpretation. They appreciate it, and it saves me time trying to come up with the 28th bicep movement of the month.

21. Balancing “Push vs. Pull” Is Not Just Sets and Reps

There is a lot more to consider when dealing with balancing your push versus pull or posterior versus anterior. I think it’s much more important to consider the total tonnage and understand the imbalance most people have between the two opposites. For example, if you can bench 400 pounds and do 5×5 at 335, you would need 40+ reps using 100-pound DBs in a row pattern to simply match the tonnage. If you did 5×5 to even things out, or even 3×10, you probably wouldn’t do it justice. I tend to program more reps—significantly so—for pulling patterns to account for the discrepancy in pressing dominance for most people.

Nothing’s Written in Stone

This has been a blueprint of my views on training, and how we at Exceed Sports Performance & Fitness go about our day-to-day. I don’t assume everyone’s situation is the same as mine, so it is unlikely that we will all agree on each point, but I think there is something in here for everyone. There’s a chance some of my assertions will change over time, but I feel fairly confident that almost all of what I wrote will not.

As always, I am up for a chat or a comment to help me reconsider anything I write or believe, so reach out if you are inclined. A few of the points probably deserve a little more depth and time, so I’m hoping I can elaborate more on them in 2021, and maybe you can help reshape how I think of them. Happy New Year!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF