Recently, I realized that I may have reached the halfway point of my coaching career. The thought made me sick to my stomach.

20 years I’ve been doing this—this amazing, heartbreaking, joyous, exhausting, energizing thing. But the track coach with 40 years of experience is rare, so I began to wonder: am I already coming into the second turn? I hope not, but nothing in the future is ever promised and fate or circumstance could take it all away from me whether I’m ready to let it go or not. The very idea of ever not being a track coach feels like a funeral.

Since that moment, I’ve been trying to put my thoughts together and reflect on what these 20 years have taught me. Every time I think about it, I get dizzy. I’m so often focusing on what’s next that it can be hard to think back on what’s already been. But I also get the sense that if the future is to yield meaningful significance, I’d better try to pin down what the past has meant. It’s awful hard to run the second half of a race harder than the first, but I’m sure going to try.

I’ve spent a lot of time making sense of the last two decades and I’ve arrived at two certainties:

- This sport has utterly changed my life.

- I never want people to stop calling me Coach.

How It Started

In the early 2000s, the phrase “mental health” wasn’t yet part of the American lexicon, so I didn’t know I was depressed. I played football and basketball, but by sophomore year the shifting of social circles and a unique brand of millennial-teen cruelty left me feeling unseen and alone. Then, someone encouraged me to join the track team. I know now what my coaches saw, because I’ve seen the same thing in the hallways at school: those tall, lanky kids who are already decently athletic football and basketball players are a no-brainer fit for giving track and field a try.

Mike Nesbitt is a Mighty Mouse of man who eats, sleeps, and breathes track and field. His dad and uncle were both track coaches. Mike was a D2 collegiate runner. At 15, I’d never met anyone who cared about running the way he did. I didn’t get it. I hadn’t had him as a teacher yet, but Coach Nesbitt approached me in the hallway and urged me to consider track and field. I’d never run before.

“It will help you stay in shape for football and basketball,” he said. “Who knows, you might just end up being a high jumper and a long jumper?”

I wasn’t sold at first, but Rich Syring—a gruff anomaly who was both my hard-nosed football coach and my kind, gentle creative writing teacher—was also on the coaching staff. Looking back, I wonder if Coach Syring saw an athletic kid with a case of the gloomies and thought physical activity in the spring would be better for me than going home and sitting idly for three months.

The storybook version would probably read that track and field suddenly became the passion I didn’t even know I had, that I became an all-state athlete, and that I beat my struggles with mental health. But, here’s the truth: track was good, I was average, and I’m still fighting. But track did change my life, even if only in the smallest of ways—I had never considered running track, and now I was on the team. It was the first domino. Funny how so often teachers and coaches are the people who nudge the first one over.

I stayed on the team for the rest of high school. By that time, enough successive dominoes had fallen that I knew I wanted to be a teacher and a coach, but I had no idea I’d get my first crack at coaching so soon. In the same way he invited me to join the team as a sophomore, Mike invited me to join the staff as a college student. I was going to school locally, and he needed help with hurdlers. I volunteered a couple times a week, coaching kids who had been my teammates the year before. I was 18. I’ve been coaching ever since.

Affecting Eternity

I think the reason I share this history is because I doubt Mike Nesbitt or Rich Syring knew they were altering the entire course of the rest of my life when they invited me out for the team; or, again when they offered me a place on the coaching staff. If you’re a teacher or a coach, there’s no telling how many people’s lives you’ve changed. Most will never tell you. Some don’t even know. But the reality is that in this role, we impact kids’ lives every single day. Hopefully, more often than not, it’s in a positive way.

If you’re a teacher or a coach, there’s no telling how many people’s lives you’ve changed. Most will never tell you. Some don’t even know. But the reality is that in this role, we impact kids’ lives every single day. Share on XThere’s a poster with an inspirational quote from Henry Adams that you’ve probably come across at some point in your life (or at least some paraphrased version of it).

I don’t know if Adams ever ran the quarter, but his insight applies to coaches, too. Because Mike Nesbitt was my coach, I became a coach. Because I became a coach, the things I’ve learned from him have been passed on to hundreds of other kids. If any of those kids improved as athletes or grew as people from the workouts I wrote or the lessons they learned, it came from Mike too. And if they pass those methods and values on….well, you get the idea. The same is true of every mentor I’ve ever had. I wonder who their mentors were, who else they were coached by, how far back eternity goes. And with an eye on the horizon, I can’t help but wonder if any of the kids I’ve worked with in the last 20 years might one day join the coaching ranks. Coaches affect eternity.

With an eye on the horizon, I can’t help but wonder if any of the kids I’ve worked with in the last 20 years might one day join the coaching ranks. Coaches affect eternity, says @TrackCoachTG. Share on XLessons Learned

When I first started helping out at Bay City Western, I remember feeling privileged to coach at my alma mater. I had proudly worn the brown and gold as an athlete, and since I never became a UPS driver, those years coaching with Mike and Rich would be the last time I donned those colors. There, I learned the importance of building a program kids want to be part of.

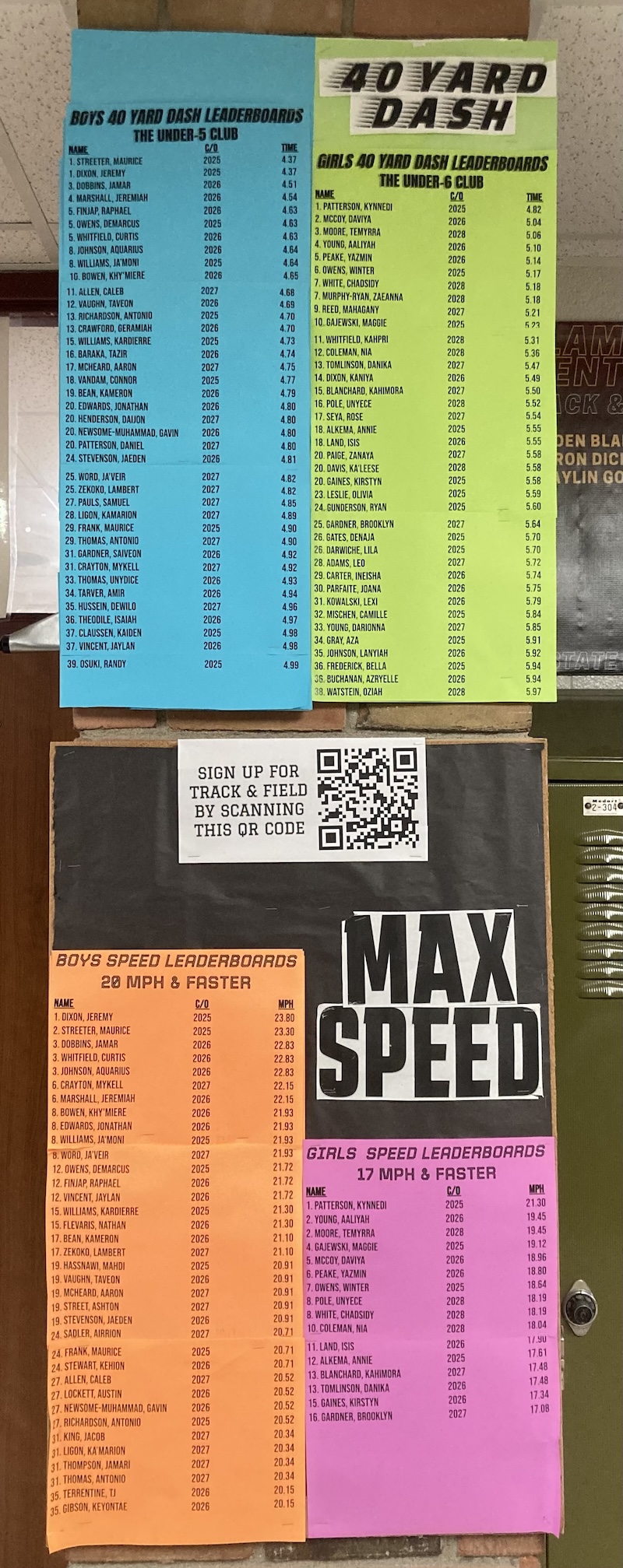

We designed workouts that were challenging but fun, a concept that was novel to me at the time. I don’t think I’d ever equated “hard work” with “enjoyment” before, but a seed had been planted that I now recognize in my current coaching: the ideal of gamifying training. Many of my favorite coaches today—people like Tony Holler, for example—are ones who have found a way to make practice the best part of a kid’s day. Kids want to be challenged, and if we can do that in meaningful ways while measuring what matters, it follows that kids will have fun. If you don’t believe me, try timing sprints in practice and creating a sprint leaderboard. Your kids will literally beg you to let them keep trying to beat their best time.

Try timing sprints in practice and creating a sprint leaderboard. Your kids will literally beg you to let them keep trying to beat their best time, says @TrackCoachTG. Share on X

In those first years of coaching, I also learned (though maybe not at the time) how important it is to have the right people on your coaching staff. Sometimes, it doesn’t matter what expertise someone has; if they’re not the right person for the kids, or they don’t jive with the rest of the staff, or their vibes aren’t right for the culture you’re hoping to build in your program, it’s not likely to work in the long run. On the flip side, I would gladly take a coach on my staff whose track and field knowledge is limited, as long as they are willing to learn and are a source of positivity and encouragement for our athletes. Every good program starts with good people.

Everywhere I’ve ever coached, I’ve learned something new.

After college, I took my first full-time teaching job in Benton Harbor, Michigan—for the first time in my life, I saw firsthand the struggles that face inner-city schools. It was eye-opening, both from the perspective of a teacher and also as a coach. With limited resources, we made the most of what we had, but many of our athletes lacked the appropriate clothes, shoes, equipment, nutrition, support, or transportation to train and compete consistently.

This was also my first time working inside a sprint-heavy program, and I had a chance to work with tremendously-gifted athletes. I coached two hurdlers—a boy and a girl—who qualified for state finals in the 300 meter hurdles. The young man ended up finishing fourth. Throughout the course of that season, I remember feeling frustrated: I had an idea of the training I wanted our athletes to do and how hard I wanted them to work, but neither one of those athletes ever made it to a full week of practice. Looking back, I think this may have actually been a good thing: I was almost certainly planning to overtrain them.

We will not be outworked, I thought.

But their inconsistent attendance meant that they were rested, recovered, and able to perform their best at the end of the season. Now, 14 years later, I can see I had cats. I definitely wasn’t feeding them, but they also weren’t letting me drown them in a sack.

At my next stop, in Monticello, Illinois, I worked with an IHSA Hall of Fame football coach named Cully Welter. Despite our vastly different demeanors—Cully is a no-nonsense, year-round-shorts-wearing, detail-obsessed grinder—I loved working with him and consider him a friend and mentor to this day. There was a business-like culture on the team where the kids knew they were there to do a job and do it well. At meets, we would bring a shovel painted with our school’s logo and the all-caps phrase “DO WORK.” That mentality started at the top, was part of everything we did, and had clearly been established over years of consistent expectations.

I also learned about thematic programming. It was the first time I can remember hearing the terms “max speed” and “speed endurance” and learned the importance of being intentional with the organization of both sprint training and strength training, day to day, week to week, and over the course of a season to allow athletes to peak at the right time. Before then, I always had a training plan, but it was haphazard, without rhyme or reason. Honestly, just a list of workouts that seemed hard enough to get kids in shape. This intentionality was novel to me, and though my training plans today look a lot different than in 2015, my workouts are grouped thematically, spaced appropriately, and geared toward championship-season success.

My last year in Illinois, as the girls’ head coach at a school of just over 500 students, we won both a conference and sectional championship as the smallest school in the field. The excitement of that sectional meet, where we qualified for state finals in nine different events, was like nothing I’d ever experienced before and a day I’ll never forget.

The list goes on, and I keep learning.

As coaches we’re faced with new challenges all the time. It’s probably fair to say that for many coaches, no greater challenge has come our way in recent years than the Covid-19 pandemic. And while that time-warp era was unequivocally horrible and difficult for countless reasons, a funny thing happened: in isolation, my circle of influences grew larger.

If I reach a point where I feel like I’ve got nothing left to learn, I hope I’m wise enough to hang up my stopwatch, says @TrackCoachTG. Share on XThrough social media, virtual clinics, the growing popularity of podcasts, and the magic of Zoom, I connected with coaches all over the world in ways I never thought possible. I’ve made friends I’ve never met in person and learned things I’m not sure I would have learned otherwise. I’m a better coach now because of it. I don’t know what other challenges I’ll face for the rest of my coaching career, but I know I’m committed to continuing to learn, forever chasing the ideal of being a better coach this season than I was the year before. If I reach a point where I feel like I’ve got nothing left to learn, I hope I’m wise enough to hang up my stopwatch.

As American author William S. Burroughs puts it, “When you stop growing you start dying.” I want to live forever.

The Moments We Live For

To a non-sports person, it can sometimes be hard to understand why we, as coaches, pour so much time and energy into something like this. At the end of the day, as important as the sport of track and field is to me (and probably to many of you reading this) it’s still a game. It doesn’t determine anyone’s value as a person, and the results are far from life or death. When you add up the hours spent planning, making meet entries, doing administrative work, and attending meets, and then throw in the money we spend out of our own pockets and compare it with the paycheck, it’s not a financially sound pursuit.

But anyone who has ever coached, especially at the high school level, knows that it’s never about the paycheck. It’s about moments.

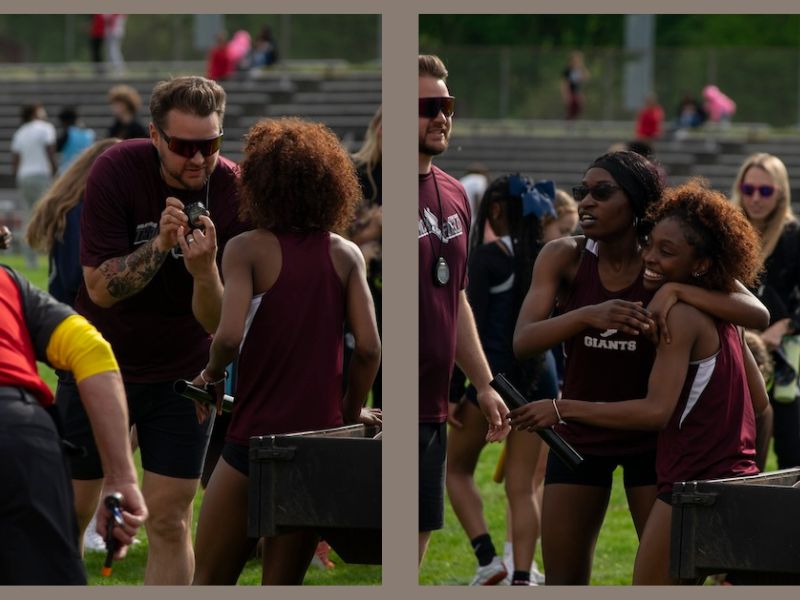

I can remember the first time I had a hurdler qualify for state finals: the elation in her face as she jumped up and down across the infield before leaping into my arms for a tearful hug. I can remember the spontaneous singing and dancing in the Wendy’s lobby on the way home from an invitational. I can remember consoling tearful young men who had learned of the unexpected passing of a close friend from another school. The pride I felt when an athlete fell on a hurdle at a big meet, only to pick herself up and finish the race. The disappointment of dropping a baton in the 4×200 at state finals, followed by the excitement of bouncing back less than an hour later to medal in the 4×100 with a school-record-breaking performance. The joy of winning our first state championship. The conversations with other coaches. The bus rides. The overwhelming feeling that the whole of what we do is so much greater than the sum of its parts.

Anyone who has ever coached, especially at the high school level, knows that it’s never about the paycheck. It’s about moments, says @TrackCoachTG. Share on XThese are the moments we live for as coaches. And, if we’re viewing this thing through the appropriate lens, we begin to see clearly that we’re in the business of creating moments. Athletes remember the experiences they have in sports, good and bad. They might not remember the outcome of a specific race or who they faced at a dual meet in April, but they’ll remember the feeling of being part of something. They will learn—knowingly or not—that sports are often an avenue for the lessons that serve us in life: lessons about dedicating yourself to something, about working hard to improve, about being a teammate, about resilience. They’ll learn about the joy of victory and the frustration of defeat, and how to deal with both.

My wife, who is one of those non-sports persons, has stood next to me at our home invitational and watched high school kids—who look like grown adults—run over to me with the enthusiasm of a six-year-old wanting to show off the spaceship they just built out of Legos. “Did you see me!?”

Each practice, each meet, each race is a chance for a kid to feel seen. It’s something so many kids need. It’s something I needed. Even a non-sports person can find the value in that. I think a lot about a simple statement she has made to me on a handful of occasions: “What you’re doing is good.”

When I think about *good,* I think about the noun, not the adjective. Sure, we do good things. But more importantly, we *do good,* says @TrackCoachTG. Share on XWhen I think about good, I think about the noun, not the adjective. Sure, we do good things. But more importantly, we do good. If we take this responsibility seriously, we strive to do good in the world, to embody good, and to teach our athletes to focus on the good around them. I think this mindset is crucial for this generation of kids, and I hope they carry it with them beyond the walls of this school. There’s an awful lot in this world that isn’t very good. It can be easy to dwell on the negative. But good is everywhere if we are willing to look for it—and if and when we find it, we celebrate like hell.

New Year, Same Mission

So here I am, in the spring of 2025. With the same cyclical certainty of the moon phases or the spring equinox, on the second Monday of March, I’ll start another track season, just like I have every year since I was 15. This new season will be my 21st as a coach.

The anticipation and uncertainty that precedes a new season is wild. I know what we have on our team, but it’s a long road to June and so much can happen between now and then. So little is in our control. For the next 83 days, I’ll be reminding myself as much as I remind my kids: show up, be present, stay the course, control what we can, let go of the rest. And—most importantly—enjoy the ride. The days are long, but the years are short, and this season will be over in the blink of an eye. Sadly, so will their high school athletic careers. I know it’s true, because I blinked and now I’m almost 40-years-old. And if I blink again, I’ll be retired. There’s a lot I hope to do before then.

I believe every kid deserves to have a great coach, and I want the ones in our school to have the opportunity to be a part of something exceptional says @TrackCoachTG. Share on XI believe every kid deserves to have a great coach, and I want the ones in our school to have the opportunity to be a part of something exceptional. There will be wins and losses, championship celebrations, and, almost certainly, there will be hardships and heartache. Our legacy is defined by what we leave behind for others, and I hope I can leave this program better than I found it—and, then, hand it off to someone who will make it better still.

But more than anything, in the chaotic whirlwind of struggle and joy, I hope that the kids I’m working with today will have moments and memories they can hang on to forever. I’ve collected quite a few of those treasures over the years and I know my collection will keep growing. When I cross the finish line, this collection will be all that remains. I hope it will be enough. It’s true that someday I won’t be coaching. Neither will you. But even after our final seasons end, I have to wonder: will we ever stop being “Coach”?