Most Strength and Conditioning (S&C) coaches primarily aim to design gym programmes which yield positive results and transfer to improved sport performance. In many cases, improved multidirectional speed is a key performance indicator for a successful S&C programme.

Within my role, I work as a private S&C coach with a variety of individual athletes, teams and coaches on athletics, soccer, tennis, netball and field hockey. My job is to identify potential limiting factors which may aid or hinder speed performance, work out how to measure these, and ultimately select the most optimal way to improve them.

From data I’ve collected over the past five years with a variety of athletes, I haven’t found a metric which correlates with speed performance measures more strongly than the countermovement jump (CMJ), says @tommymunday1. Share on XThe Vertical Jump and It’s Link with Speed

Cue the vertical jump. With performance determined by rapid and forceful hip and knee extension, it is clear to see some performance factors which overlap and aid with multidirectional speed.

Jump height is determined by the amount of impulse and force an athlete is able to generate when the only resistance is their own bodyweight.

Rapid and forceful hip and knee extension has some crossover with accelerating, decelerating, and even top speed qualities.

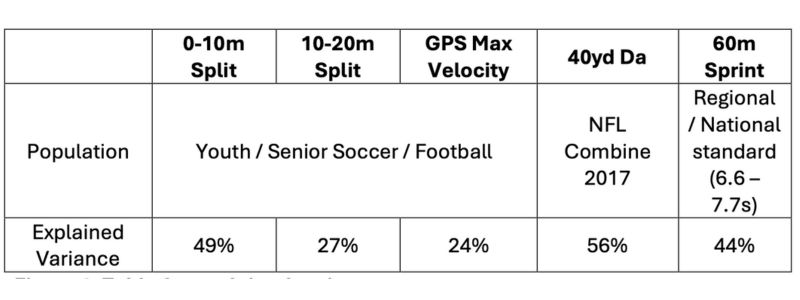

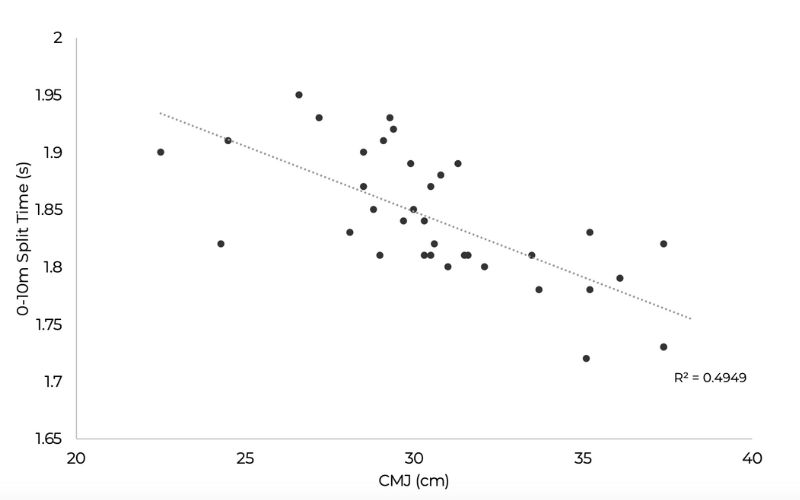

As part of training and testing, I measure speed using timing gates and StatSports GPS technology, and use Output Sports or OptoJump data for measuring jump height or reactive strength. From data I’ve collected over the past five years with a variety of athletes, I haven’t found a metric which correlates with speed performance measures more strongly than the countermovement jump (CMJ). Depending on the test, distance, and population, explained variance is typically moderate to very strong, with jump height being a good predictor of an athlete’s capacity to be quick.

The table below summarises various bits of open-source data and numbers I’ve collected or found from a variety of populations.

Within soccer, acceleration and speed in the first 3-5 steps are crucial to create or deny space within time constraints, so a link between CMJ height and 0-10m speed is useful information when a coach wants to increase the chance of developing this quality.

When we look at the data within the same population (youth soccer), we can see that as distance increases, the strength of the association decreases. Logically, this makes sense—as distance increases, ground contact times become shorter, a focus shifts from muscular “pushing” to tendon “bouncing” and qualities which support a higher vertical jump seem to become less relevant, but still explain some relatively high variation of performance.

A Damien Harper study from 2020 finds that athletes who can jump higher also have better deceleration performances and qualities than their lower-jumping counterparts. For the most part, we can be reasonably confident that training which moves the needle on an athlete’s jump height will improve qualities which can also contribute to development of speed in multiple directions.

What Kind of Training Does an Athlete Need to Improve Their Jump Height?

My preference is to start by measuring an athlete’s countermovement jump with the hands on their hips. I’ll then get a score, but without context this isn’t much use to me.

The next job is to repeat the test with different task constraints, to work out why they are jumping the height they are, and to infer how to best improve this.

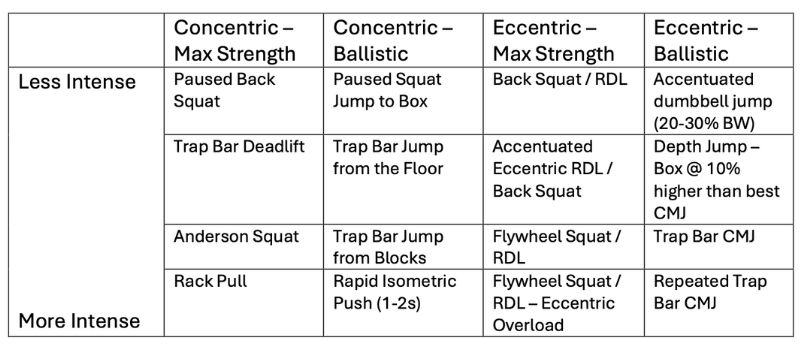

For the most part, we can be reasonably confident that training which moves the needle on an athlete’s jump height will improve qualities which can also contribute to development of speed in multiple directions, says @tommymunday1. Share on XDepending on the athlete, selected development exercises can either focus on maximum strength or more ballistic-focused rate of force development (RFD) work. This will usually follow a more concentric or eccentric theme to further challenge qualities which contribute to development of the jump—and in turn contribute to multidirectional speed.

Heavier resistance work such as squats or deadlifts may be appropriate, equally alongside loaded ballistic work such as power cleans and loaded jumps, or bodyweight jumps often using boxes in various formats. The detail is in selecting the appropriate exercise, intensity and volume to ensure continual progress is made.

Eccentric or Concentric? Paused Squat Jump—Eccentric Utilisation

After the initial CMJ, the next assessment is to repeat the test with a three-second pause at the bottom of the jump, followed by a rapid acceleration out of the hole. This variation relies much more heavily on rapid concentric force production, recruiting motor units rapidly without a prior alert from the CNS, created from the eccentric stretch-reflex.

Video 1. CMJ Testing.

Video 2. Paused Squat Jump Testing.

The difference between the paused squat jump and the countermovement jump can be quite useful info. This is often referred to as the “eccentric utilisation ratio,” as it indicates how effectively an athlete has loaded up when descending and how effectively their body has used the benefit of the eccentric phase to generate a more forceful propulsion back out.

This ratio can be calculated from:

-

(CMJ – SJ) / CMJ

Athletes with large differences between the two jumps (>15%) often appear to be very elastic in their nature, often taking some time and using lots of range to wind up and power out of the jump.

Athletes with small differences (<10%) often appear to be quite explosive and potentially don’t use lots of range or speed during their eccentric phase of the jump. Athletes who are eccentrically weaker or slower may have little difference and not benefit much from the eccentric phase of the jump.

Athletes with large differences between the two jumps (>15%) often appear to be very elastic in their nature, often taking some time and using lots of range to wind up and power out of the jump, says @tommymunday1. Share on XIt should be noted that there is no research linking EUR performance and sport performance. For that reason, a high or low EUR wouldn’t mean an athlete is automatically fast or slow. I’m, therefore, not too concerned about comparing EURs between athletes, but it can be very useful when comparing an athlete against themself to help identify what we will specifically work on to target their CMJ.

My preference is to prescribe more eccentrically-themed gym work for athletes in the second category, and more concentrically- or isometrically-themed gym work for athletes in the first.

For athletes between the two, they’ll tend to do a bit of both, depending on what the programme allows and can cater to.

EUR – General rule of thumb

- <10% – Eccentric-themed gym work

- >10% – Concentric-themed gym work

Once we’ve identified a more appropriate contraction type for a programme, the next job is to work out whether a programme should prioritise developing the magnitude or rate of force development more.

Establishing a Loaded Jump Profile—Does the Athlete Need to Work on Max Strength or RFD?

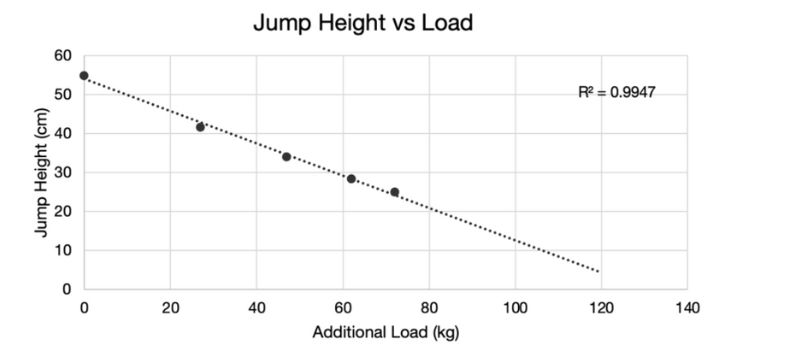

After the hands-on-hips CMJ, we can again change the task’s constraints by adding additional load in the form of the trap bar jump. This is biomechanically very similar, and for this reason we see strong linear trends when plotting height against additional load.

I’ll typically get an athlete to perform sets of one to three trap bar jumps with increasing loads for between four and seven sets, aiming for an R2 value of 0.97 or higher within a trendline.

Video 3. Creating a loaded jump profile with the Bosco Index.

I’ll tend to keep loading an athlete up by 5-20kg at a time and keep doing sets until they are jumping less than 50% of their original unloaded CMJ.

As load increases, an athlete is afforded more time and mass to generate higher forces over extended time frames, provided they have the maximum strength qualities to do so.

Due to a lack of maximum strength, athletes with steep trendlines will have their jump heights drop off very quickly under increased additional load.

Performance improvements are often fairly predictable and can be normally attributed to a key exercise which has been used, says @tommymunday1. Share on XAthletes with a shallower trendline will have their jump height drop off more gradually. With longer contraction times afforded, they are able to generate higher forces and impulses to move themselves plus heavier additional loads with some decent momentum. However, when only their own bodyweight (and less time) is available as resistance, they may lack the RFD qualities to recruit motor units rapidly and demonstrate their strength in an unloaded vertical jump.

Athletes in the second category should prioritise exercises which encourage and allow them to generate the high forces they are capable of in reduced time frames.

Athletes in the first category, however, should prioritise max strength training, and lift the lid on the amount of force they are able to generate through motor unit recruitment and, in some cases, muscular size.

The Bosco Index

We can quantify the steepness of the trendline using the Bosco Index. When an athlete first comes in, we’ll take their body mass. Let’s say it’s 80kg. We’ll then use the load vs. jump height trendline to forecast what they would jump with 1 x their body mass, or 80kg additional load. This is then divided by their CMJ.

Bosco’s Index for this loaded jump is recommended to sit at 0.33, or one-third of their CMJ. That is, an athlete jumping 45cm should jump at least 15cm with 1x their body mass as additional load.

If they can, this removes the doubt that maximum strength is a limiting factor to their jump performance. If they can’t, they can most likely still benefit from getting stronger.

Even though this research was published in the early 90s, it’s stood the test of time. From the hundreds of profiles I’ve collected over the past few years, the mean, median and mode average value for the Bosco Index sits at 33%.

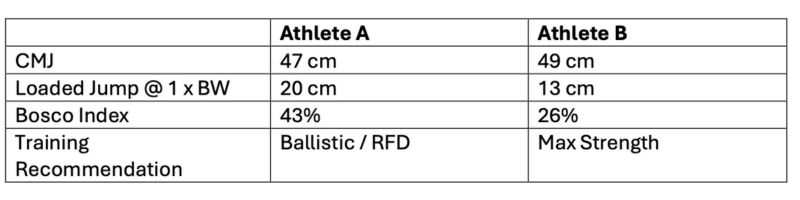

An interesting case study which brings this data to life is two U18 sprinters who performed these tests.

Athlete A had a very shallow trend line, and was relatively not affected too much by additional load.

Athlete B, however, was very affected by additional load, dropping off rapidly. We can infer that Athlete B can jump high because they’re able to access a lot of the force they can generate quickly, unlike athlete A, who is able to generate high forces but was lacking the ability to recruit and access this quickly.

Bosco Index – general rule of thumb

- < 0.33 – Prioritise max strength

- >0.33 – Prioritise ballistic work / RFD

Putting It Together

Exercise categories can form a quadrant, adopting both themes to address an athlete’s development area for a higher vertical jump and improved qualities to contribute to speed development.

I’ll typically run with an exercise as a key lift for a session 1-3 x per week for four weeks, then repeat the tests.

Case Study — What Does this Look Like in Practice?

Testing on an appropriate day allows the coach to track change and adaptation with an athlete.

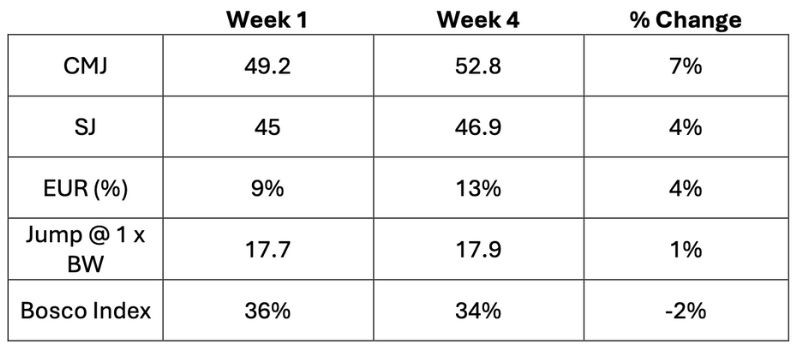

An example case study would be some recent work with a senior professional soccer goalkeeper with a good training age and extensive background for S&C. Below you can see the initial testing results, programme, and outcome. The athlete’s results were as follows:

- CMJ – 49.2cm

- SJ – 45cm

- EUR – 9%

- Jump @ 1 x BW – 17.7

- Bosco Index – 36%

- Outcome for training theme – Eccentric – Ballistic

Two key exercises were a depth jump from a 50-60cm box and a Trap Bar CMJ at a load which yielded the most impulse. The aim was to improve the rate of eccentric force production—with the athlete loading more forcefully and more quickly.

After four weeks of eccentric themed training with a ballistic emphasis, significant improvements were made in the CMJ and SJ, although we can see that they were more pronounced in the CMJ, with the athlete now using the benefit of the eccentric phase more effectively.

The next phase would focus on concentric-ballistic work, based off the athlete’s new profile.

For the past 2-3 years, I’ve been using this programming method with a number of athletes to make consistent, long-term improvements with the CMJ. Manipulations in volume and intensity are made around key competitions, but periodisation around training themes is largely unplanned and follows the profiling and testing data.

Performance improvements are often fairly predictable and can be normally attributed to a key exercise which has been used. For example, after a block of max strength work, there will be greater improvements in loaded jump performance than there will in the CMJ. After a block of ballistic work, the loaded jump tends to maintain or very often there will be a slight drop in performance, representing a slight reduction in max strength. However, this allows the coach to reintroduce this as a stimulus and keep making consistent improvements with the athlete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Bosco, C. (1999). Strength Assessment With the Bosco’s Test. Italian Society of Sport Science. https://www.scribd.com/document/215051255/Bosco-Strength-Assessment-1999

Harper DJ, Cohen DD, Carling C, Kiely J. Can Countermovement Jump Neuromuscular Performance Qualities Differentiate Maximal Horizontal Deceleration Ability in Team Sport Athletes? Sports. 2020; 8(6):76.

NFL Combine Data: www.profootballreference.com.