Brazilian jiu jitsu (BJJ) is a grappling sport that was derived from Judo in the early 20th century. Long-time Judo practitioner Mitisuyo Maeda spent significant time traveling around the globe spreading knowledge and teaching Judo techniques to students in various countries. Eventually, he crossed paths with Brazilian natives Carlos and Helio Gracie, who took the techniques they learned from Maeda and adapted them to fit their physical capabilities more appropriately, which did not include size or strength.1 This is widely considered the birth of BJJ, which allows the smaller or less physically gifted individual to defeat a larger opponent through technique.

Since its inception, BJJ has grown in popularity, primarily due to its successful use in mixed martial arts (MMA) fights and self-defense situations.2,3 As BJJ has grown in popularity, so too has the research behind the physiological makeup of the BJJ athlete and effective training methods to develop strength, power, and endurance for grappling. Sound technical and tactical strategies will always remain the backbone of success in jiu jitsu; however, developing strength, power, and endurance are now a critical piece of the puzzle for hobbyists and elite practitioners who wish to maximize their potential. In order to improve said physiological qualities, one must first understand the demands of BJJ on the athlete and the appropriate training strategies to improve performance potential.

As Brazilian jiu jitsu has grown in popularity, so too has the research behind the physiological makeup of the BJJ athlete, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on X[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11130]

The Breakdown of BJJ

As previously mentioned, BJJ plays a major role in the overall arsenal of many MMA fighters, but it is a competitive sport in its own right, too. BJJ matches are classified as “Gi” or “No-gi,” where the athletes are either wearing a thick kimono (known as a gi) or tight compression apparel, respectively. Both styles of BJJ have their own technical nuances, but the overarching goal of both styles remains the same.

Every match begins with both athletes standing and attempting to either take their opponent down or pull-guard (attacking from the bottom position). The objective is to win by securing a chokehold or joint lock, which ultimately forces the opponent to submit or “tap” to avoid being strangled unconscious or suffering injury from joint manipulation. If neither grappler can submit the other, the grappler who accumulated the most points for dominant positions is awarded the win for the match.

Match length varies depending on one’s skill level and rank with the following times being most common:

- White belt: 5 minutes

- Blue belt: 6 minutes

- Purple belt 7 minutes

- Brown belt: 8 minutes

- Black belt: 10 minutes

Elite or professional jiu jitsu athletes may have only one match against a predetermined opponent as in MMA; however, the overwhelming majority of BJJ matches occur in tournament-style brackets, where an athlete may have 4-5+ matches in one day. This style of competition and the training itself place a huge demand on the athletes, requiring them to prepare with sound strength and conditioning methods for optimal performance outcomes.

Strength

While BJJ relies heavily on technical ability to defeat an opponent, strength underpins the ability of the athlete to express said abilities against another skilled opponent, making it an important attribution to the overall makeup of a BJJ athlete.4 Research by Andreato et al.5 has demonstrated that BJJ athletes possess excellent abdominal/upper body strength and endurance, as well as high levels of isometric low back strength. More specifically, grip strength, pulling motions (dynamic strength), resisting positional advances against an opponent (static strength), and holding an advantageous position all require high levels of strength from the BJJ athlete.1

BJJ athletes possess excellent abdominal/upper body strength and endurance, as well as high levels of isometric low back strength, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XThe degree to which strength ultimately determines success in a BJJ match is difficult to quantify due to the collective variables at play, including technique, experience, weight division, and fatigue. Regardless, with the findings from this research along with a biomechanical analysis of the sport, it could be argued that developing an adequate level of maximal strength and subsequent strength endurance, particularly through the upper body/trunk area, aids BJJ performance positively.5

Power

BJJ requires slow/static movements to control one’s opponent and apply force during submissions; however, several instances occur where these movements need to be executed in a rapid fashion. A match can end in a matter of seconds or grind for 10+ minutes (black belts). Research demonstrates that during the average competitive BJJ bout, each 117-second block of work contains four 3-5 second expressions of high intensity effort followed by 25 seconds of lower intensity work, bringing the “Hi:Low” work to rest ratio (HI:LO) to around 1:5.6,7,8 This indicates that the adenosine triphosphate phosphocreatine system (ATP-PC) is in fact an important part of the BJJ athlete’s performance make-up, as it is the primary fuel source for these high force expressions.8

The high force expressions include things such as takedowns, throws, positional/submission escapes, and certain submission applications. A high level of technical mastery is required to apply high force with a technique at a particular time to induce a successful outcome. It is particularly advantageous for a BJJ athlete to possess adequate rate of force development (RFD) ability relative to their body weight, as they compete against athletes that are the same size as they are more often than not.9

Endurance

A BJJ athlete requires both anaerobic endurance and aerobic capacity to be well suited for competition.10,11 The ability to withstand the acidosis produced from buffering hydrogen ions during a bout is key for the athlete’s ability to maintain grip controls, frame against their opponent, apply submission techniques, escape, and perform nearly all other continuous activities involved in the sport.5 However, when it comes to training, direct comparisons between methods of preparation for BJJ and other grappling sports (such as wrestling and Judo) have led to confusion.

A BJJ athlete requires both anaerobic endurance and aerobic capacity to be well suited for competition, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XJudo, for example, typically only contains 30-37 seconds of work followed by 10-15 seconds of rest, or a 3:1 work to rest (W:R) ratio, whereas BJJ contains around 117 seconds of work with a 20-second pause, or 6:1 W:R ratio.10,12 This paucity creates confusion amongst researchers and practitioners who may equate the conditioning needs of a BJJ athlete to that of other grappling sports when in fact it is quite different.10

Aerobic capacity contributes to the recoverability both within and between matches for the BJJ athlete. As matches get longer and closer to the 10+ minute mark seen at the black belt level, aerobic capacity becomes even more pertinent.1,8,11

Injuries and Mobility

One of the known dangers of competing and training in a grappling sport is the inherent risk of injury. BJJ athletes are attempting to manipulate one another’s joints to the point of damage prior to forced submission, which, when combined with chaotic scrambles for dominant positions or unpredictable counter movements from the opponent, can lead to an array of both acute and chronic injury accumulation over time. This is due to the compression, torque, and wear/tear on the body that occurs in training and/or competition. One research study by Scoggin et al. examined the prevalence of injury occurrence during BJJ competition and found an injury rate of 9.2 per 1000 exposures, 78% of which were orthopedic.13 The elbow joint was most injured due to the “arm bar” joint lock submission, occurring twice as often as knee injuries and three times as often as ankle/foot, hand, and shoulder injuries collectively.

Considering whether these types of injuries are preventable or not is an interesting concept. Competition is particularly chaotic and unpredictable, meaning that anything can happen. Interestingly, a vast majority of injures appear to occur during training, which is far more controllable, suggesting that coaches and athletes could more closely monitor training scenarios so that risk for injury is reduced.14 In addition, BJJ athletes can certainly make themselves more robust and resistant to injury by obtaining adequate mobility through the shoulders, hips, lumbar spine, and posterior chain so that they are more easily able to maintain position, recover guard, execute sweeps, and escape unfavorable positions.15

A major opportunity for further research would be to analyze common BJJ injury data and compare the training regimen, nutrition, medical history, recovery tactics, and lifestyle of the given athletes to better understand potential mechanisms of injury. Due to the nature of BJJ, injuries are always a possibility, meaning that athletes and coaches should aim to strengthen all areas of the body including the neck, shoulders, hips, knees, elbows, back, and ankle/foot to reduce the likelihood of injury occurring.

Due to the nature of BJJ, injuries are always a possibility, meaning that athletes and coaches should aim to strengthen all areas of the body, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XTraining

Devising a training plan that meets the demands of a BJJ athlete is a delicate blend of volume, intensity, frequency, and exercise selection. Performance training that detracts from or negatively impacts BJJ-specific training should be avoided. This becomes difficult from a recovery standpoint when a BJJ athlete trains 5-6 times a week for 1.5-2 hours at a time and perhaps competes dozens of times per year.

Outside of enhancing performance, several key considerations for a BJJ training program include the following:

- Most BJJ athletes compete in a specific weight class—therefore, excessive muscular hypertrophy should be avoided in most cases, unless the athlete wishes to compete at a higher weight class.

- High volume, high intensity BJJ skill sessions can put major stress on the joints and compression/torque on the neck/mid-low back. Consequently, exercises must be selected carefully so as not to further stress these areas.

- Scheduling workouts throughout the week must be done carefully to allow for enough recovery between sessions.

- Less can often be more. The overarching goal of strength and conditioning for BJJ is to provide the minimum effective dose for the desired adaptations and ultimately allow for more time to train BJJ, recover, or possibly cut weight if necessary.

Practical Application

There is no “one size fits all” programming style for the BJJ athlete due to factors such as skill level (elite vs. non-elite), age, training availability, experience, and injury history. While no two BJJ athletes’ schedules are alike, most serious competitors have their competition schedule laid out far in advance to allow for proper training camps and potential weight cutting. The examples provided below demonstrate snapshots of an eight-week periodized training cycle, which begins with strength endurance and ends with a focus on maximal strength and power.

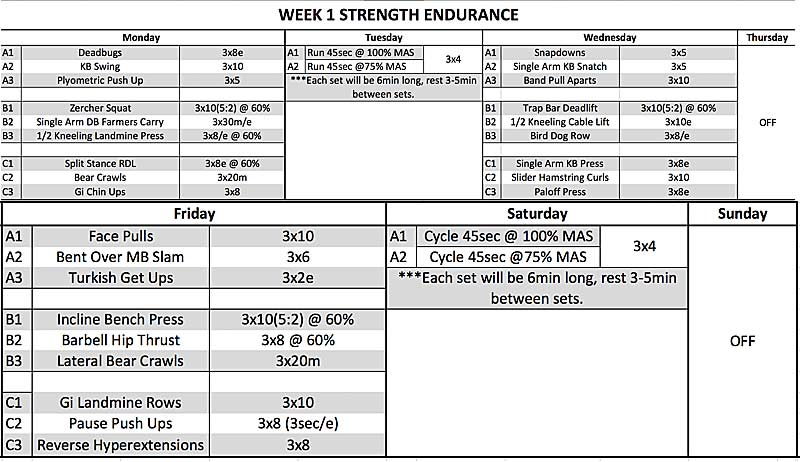

There is no “one size fits all” programming style for the BJJ athlete, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XThis would be ideal if a BJJ athlete has a break in their competition schedule or very few competitions of importance during the training period. The traditional “annual plan” where an athlete goes through extended offseason, preseason, and in season training periods does not apply to the BJJ athlete due to the fact that competitions can occur year-round and there are almost never extended periods of time where one stops training. Below is a further look at the first block of training focusing on strength endurance.

*(5:2) indicates cluster set: complete 5 reps, rest 10 seconds, and repeat until all fifteen are done.

This block is intended to build the athlete’s ability to withstand stress and workload accumulation for higher intensity training to come in later weeks. Several methods accomplish this, including cluster sets, which are a popular resistance training strategy using short periods of rest between single or groups of repetitions within a set.16 Cluster sets are used for key primary exercises such as the Zercher squat and trap bar deadlift to allow for both improved technical execution and the potential for greater load. Various exercises targeting the low back/posterior chain (reverse hyperextensions, split stance RDLs, etc.) and upper body (single-arm KB press, half kneeling landmine press, gi chin-ups, etc.) are used to address the specific needs of BJJ athletes as discussed earlier. Each session is considered a “full body session” so that volume is dispersed throughout the week, which helps reduce the likelihood of soreness and fatigue accumulation compared to an upper or lower body split routine.

Each session is considered a “full body session” so that volume is dispersed throughout the week, which helps reduce the likelihood of soreness and fatigue accumulation, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XOn Tuesdays and Saturdays, the conditioning is general and aimed at improving the athlete’s aerobic power through maximum aerobic speed training (MAS).9,17 In this example, running is used as the primary method on Tuesdays and rowing on Saturdays. While this W:R ratio is simply 1:1, it can be later adapted to meet the demands of BJJ more closely as discussed previously in the endurance section.

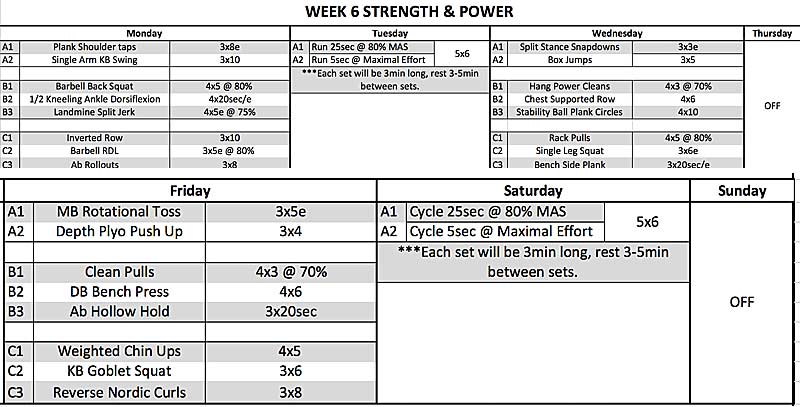

The next block highlighted below is from week 6 (of 8) in the program, where the primary emphasis has shifted towards developing strength and power.

*Mas = Maximum Aerobic Speed

*KB = Kettlebell, *DB = Dumbbell

In this block, the athlete’s volume has dropped significantly; however the intensity has also increased significantly. Exercises such as the barbell back squat and rack pull are used to initiate high force production from the athlete and are paired with contrasting high velocity movements such as box jumps and power cleans. Key areas of the body (e.g., low back, posterior chain, back, shoulders, etc.) are all still addressed as well; volume for these movements, however, is at a maintenance level in order to not overload the athlete and create undue fatigue.

The conditioning in this portion of the program is targeted at short bouts of high intensity exertions paired with intermediate bouts of moderate intensity exertion, as seen by the MAS workout on Tuesday. Saturday’s MAS workout is optional and can be replaced with a low intensity steady state session if BJJ sport training is becoming more pertinent and higher intensity.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9064]

Balance

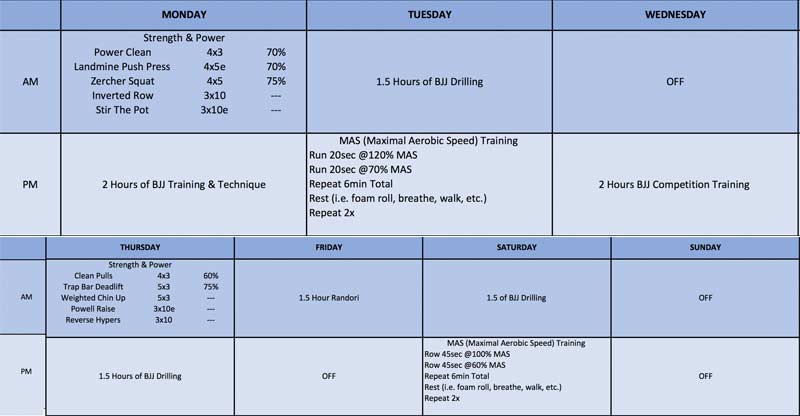

Balancing a weekly schedule in BJJ training is a difficult task, as previously mentioned. A fine line exists between overtraining and under-recovering—therefore, practitioners and coaches alike must be meticulous with the way they devise their weekly training routine. The previous two training examples gave insight into how one may train specifically in the gym to improve their BJJ performance, but the example below provides insight into how one may balance physical technical/tactical training throughout the week.

A fine line exists between overtraining and under-recovering—therefore, practitioners and coaches alike must be meticulous with the way they devise their weekly training routine. Share on X

Competitive BJJ athletes will likely do some form of technical/tactical training on a daily basis, therefore the key is to set up training such that it never detracts from that. Good strategies as depicted above are:

- Dividing physical and technical/tactical training into AM/PM sessions (ideally 4-6+ hours apart):

- Strength training in the AM if BJJ is to be done in the PM so that performance is not compromised in the gym.

- Conditioning in the PM if BJJ is to be done in the AM so that performance is not compromised in BJJ training.

- Allowing a minimum of one full day rest per week.

- Oscillating between higher and lower intensity/volume days throughout the week.

- Keeping volume during strength training to a “minimum effective dose.”

Final Takeaways

BJJ is a rapidly evolving sport that requires an array of physical and technical competencies to be successful. A delicate balance exists between performance training for BJJ and actual BJJ training in that the former must be careful not to detract from the latter, but instead serve as an enhancement. Keeping the BJJ athlete healthy and ready to compete are two of the most important aspects of a BJJ training program, followed by:

- Specific endurance.

- Strength.

- Power development.

Research analyzing the specific physiological profile of elite BJJ athletes and mechanisms of injury is continuously evolving with several informative pieces of literature being published in the past 5 years alone.4,5,9,12,18 In addition to this literature, a major opportunity exists for further research to take place in analyzing the aforementioned areas of performance and physiology in BJJ.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Jones NB and Ledford E. “Strength and conditioning for Brazilian jiu-jitsu.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2012;34:60-69.

2. Buse GJ. “No holds barred sport fighting: a 10 year review of mixed martial arts competition.” British journal of sports medicine. 2006;40:169-172.

3. Stellpflug SJ, Menton WH, and LeFevere RC. “Analysis of the fight-ending chokes in the history of the Ultimate Fighting Championship™ mixed martial arts promotion.” The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 2022;50:60-63.

4. Øvretveit K and Tøien T. “Maximal strength training improves strength performance in grapplers.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2018;32:3326-3332.

5. Andreato LV, Lara FJD, Andrade A, and Branco BHM. “Physical and physiological profiles of Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes: a systematic review.” Sports medicine-open. 2017;3:1-17.

6. Amtmann JA, Amtmann KA, and Spath WK. “Lactate and rate of perceived exertion responses of athletes training for and competing in a mixed martial arts event.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2008;22:645-647.

7. Andreato LV, Follmer B, Celidonio CL, and da Silva Honorato A. “Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu combat among different categories: time-motion and physiology. A systematic review.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2016;38:44-54.

8. James LP. “An Evidenced-Based Training Plan for Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2014;36:14-22.

9. Villar R, Gillis J, Santana G, Pinheiro DS, and Almeida AL. “Association between anaerobic metabolic demands during simulated Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu combat and specific Jiu-Jitsu anaerobic performance test.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2018;32:432-440.

10. Andreato LV, de Moraes SF, de Moraes Gomes TL, Esteves JDC, Andreato TV, and Franchini E. “Estimated aerobic power, muscular strength and flexibility in elite Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu athletes.” Science & Sports. 2011;26:329-337.

11. Junior JS, dos Santos RP, Kons R, Gillis J, Caputo F, and Detanico D. “Relationship between a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu specific test performance and physical capacities in experience athletes.” Science & Sports. 2022.

12. Tonani ECF, Fernandes EV, Dos Santos Junior RB, Weber MG, Andreato LV, Branco BHM, and De Paula Ramos S. “Association of heart rate and heart rate variability with an anaerobic performance test and recovery of Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes.” International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport. 2021;21:361-373.

13. Scoggin III JF, Brusovanik G, Izuka BH, Zandee van Rilland E, Geling O, and Tokumura S. “Assessment of injuries during Brazilian jiu-jitsu competition.” Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2014;2.

14. Petrisor BA, Del Fabbro G, Madden K, Khan M, Joslin J, and Bhandari M. “Injury in Brazilian jiu-jitsu training.” Sports Health. 2019;11:432-439.

15. Del Vecchio FB, Gondim DF, and Arruda ACP. “Functional movement screening performance of Brazilian jiu-jitsu athletes from Brazil: differences considering practice time and combat style.” Journal of strength and conditioning research. 2016;30:2341-2347.

16. Latella C, Teo W-P, Drinkwater EJ, Kendall K, and Haff GG. “The acute neuromuscular responses to cluster set resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Medicine. 2019;49:1861-1877.

17. Laursen P and Buchheit M. Science and application of high-intensity interval training. Human Kinetics. 2019.

18. Tota Ł, Pilch W, Piotrowska A, and Maciejczyk M. “The effects of conditioning training on body build, aerobic and anaerobic performance in elite mixed martial arts athletes.” Journal of human kinetics. 2019;70:223-231.