Have you been scrolling social media and trying to learn the basics of running a training program? Social media is full of strength and conditioning coaches trying to show off new and complicated training methods, arguing over the nuances of Nordic hamstring curls, or bashing non-strength coaches for flaws in their programming.

If you’re a sport coach trying to run a weight room or a young S&C coach just getting into the field, none of this is helpful. You need the basic principles of S&C laid out so you can run your training program safely and effectively. In this series of articles, my goal is to do just that: communicate the basics clearly and concisely.

- Showing how to run an effective training program that can be tailored to your situation.

- Laying out critical mistakes to avoid so your athletes don’t get injured.

- Painting a clear picture of how to approach strength & conditioning if you’re not an expert.

I am closing in on my 15th year as a strength coach. In that time, I have worked with athletes of all levels: Olympians, NFL players, 5-star collegiate athletes, middle school, high school, and elementary school. I’ve coached with all the resources that the University of Texas had to offer and I’ve had to fundraise to pay for enough barbells and plates to make a high school weight room functional. That experience has given me a full picture of the field of S&C and helped shape some foundational principles that will safely build athleticism at any level.

In the first article in this series on the foundations of S&C, we will be taking the view from 10,000 feet. In the next three articles, we will dig more into the specific details on programming, exercises, and conditioning—however, I believe it’s best to understand the whole picture before diving into the deep end.

Adaptations Are the Goal

When broken down to its most basic function, strength & conditioning is the art of creating adaptations within the human body. We apply a stimulus (lifting, running, jumping, etc.) and that stimulus applies stress. When the body encounters enough stress and is given adequate time to recover, it adapts to that stress and changes.

Apply heavy loads in the weight room and the body will build bigger, stronger muscles. Apply cardiovascular stress through conditioning and the lungs, heart, and tissues will adapt to allow better endurance. Apply neural stress through challenging movement drills and the brain will adapt new movement patterns.

Coaches need to understand this fundamental framework when designing a training program. Everything we do is designed to cause adaptations within the athlete—we are stress appliers. Apply too little and athletes don’t see change. Apply too much and athletes get injured. Apply the right amount and they are transformed.

Everything we do is designed to cause adaptations within the athlete—we are stress appliers. Apply too little and athletes don’t see change. Apply too much and athletes get injured. Apply the right amount and they are transformed. Share on X

This is where it’s important for me to mention the SAID principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands). This law states that the human body will adapt very specifically to whatever stress you put on it. Athletes who only perform long, slow conditioning runs will get really good at running slow for a long time. But they won’t get fast. Athletes who only ever lift 10-15 reps will get really good at muscular endurance. But they won’t get very strong.

Movement Patterns vs. Muscles

The first major pitfall non-strength coaches make is taking a bodybuilder’s mindset into an athlete’s weight room. Bodybuilding is highly effective at one thing: building muscle. When working with athletes, however, our goals are much broader. Sure, we want to build muscle. But we also want to build strength and power. And prevent injury. And build endurance. And train speed. Bodybuilding isn’t designed to touch any of those other qualities.

So, when choosing exercises for your program, you can’t use a bodybuilding lens. To be clear: this means you can’t design your program based on having chest day, leg day, back day, and arm day.

Instead, your lens should be one that focuses on movement patterns. Sprinting, cutting, jumping, and contact can all be broken down into common human movement patterns. If we strengthen these patterns in the weight room, the results will be positive on the field of play. There are 4 major pattern categories we start with when programing:

- Lower Body Push (Squat/Lunge)

- Lower Body Pull (Deadlift/RDL/Cleans)

- Upper Body Push (Bench/Incline/Overhead press)

- Upper Body Pull (Rows/Pull-up)

Your lens should be one that focuses on movement patterns. Sprinting, cutting, jumping, and contact can all be broken down into common human movement patterns, says @DNeill62. Share on X

In addition, some coaches will add Rotation as a pattern and give Olympic variations their own category. But, for simplicity, you should choose 3-4 compound exercises* in each pattern. Make these exercises the meat and potatoes of your program. The goal is to progressively overload each exercise to build strength and power over the course of a training cycle.

Planning a fairly-even balance between categories is also important. Too much pushing and not enough pulling can create imbalances in the shoulder that put athletes at risk for injury. Too much squatting and not enough posterior chain work limits overall lower body strength gains. You get the idea.

*Compound exercises are multi joint movements that use multiple muscle groups to accomplish general strength tasks. Think squat, bench, lunge, cleans vs biceps curls or leg extensions.

| Lower Body Push Exercises | Lower Body Pull Exercises |

|---|---|

|

|

| Upper Body Push Exercises | Upper Body Pull Exercises |

|

|

Table 1. Common, staple exercises coaches use for each category.

Don’t Make These Mistakes

We will dig into the details of programming in later articles, giving you tools to make competent decisions as you design your training plan. From the start, however, I want to identify the most common mistakes I see uninformed coaches make in their programs, as the following half-dozen mistakes will hurt your athletes.

1. Too Much, Too Fast

Want to get fired…and face multiple lawsuits on top of that? Give a bunch of kids Rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdo occurs when an athlete trains too intensely, too soon after a significant break. The muscles of the body accumulate more damage than the body can repair, flooding the blood stream with proteins and overwhelming the kidneys.

The muscle tissue swells up, CK* counts shoot through the roof, and the athlete will be hospitalized. In extreme cases, the athlete can die. Two weeks of acclimation training can prevent this. Spend the first two weeks of training with lowered volume and less running so that athletes’ bodies can adapt. No bootcamps, no hell weeks, no “setting the tone” workouts during this period. This also saves the more intense training stimulus for later in the program when it is needed for progression.

Spend the first two weeks of training with lowered volume and less running so that athletes’ bodies can adapt. No bootcamps, no hell weeks, no ‘setting the tone’ workouts during this period, says @DNeill62. Share on X

A couple of things to remember: the smaller muscles of the upper body—especially forearms and biceps—are the most susceptible to the damage that can lead to rhabdo. Keep the curl competitions out of the program in the first two weeks. Athletes who are previously well trained are also more susceptible. They have the mental and physical capability of training extremely hard, but their bodies can’t keep up until they acclimate.

After extended breaks, I like to implement a two-week block focused on rebuilding movement patterns with lighter loads. We will use tempo goblet squat, pushups, assisted rows, and RDLs. This prepares our patterns for the heavier lifting to come and prevents detrained athletes from overdoing it during this precarious period.

*Note: CK is short for Creatine Kinase, an enzyme found in skeletal & heart muscle. When levels are dangerously elevated from excessive muscle damage, kidney damage/failure can occur and even death in extreme cases.

2. All Conditioning, Zero Speed

The Old School approach is “we will get our guys in better shape than anyone else, at any cost.” As mentioned earlier, the problem is that when all you do is run long and slow…you get really good at running slow. There are, no doubt, benefits to building aerobic capacity and developing the energy systems athletes will use in sport. But to play fast, you have to train fast. A significant portion of your field training should be focused on acceleration, max velocity, sport specific agility, and timed sprint testing. If all of your outside work is 100s and gassers, you’re going to have a slow team.

To play fast, you have to train fast. A significant portion of your field training should be focused on acceleration, max velocity, sport specific agility, and timed sprint testing, says @DNeill62. Share on X

3. Impossible Percentages

Occasionally you will see a Twitter post with a whiteboard workout that goes something like this:

5×10 Back Squat @90%

5×10 Bench Press @90%

5×10 Deadlift @90%

Etc…

Not only is this a great way to get kids hurt, it’s also physically impossible. Years of research has shown that there are upper limits to what percentages an athlete can perform at given rep ranges. According to the NSCA,1 the absolute limits are:

1 Rep 100%

2 Reps 95%

3 Reps 93%

4 Reps 90%

5 Reps 87%

6 Reps 85%

7 Reps 83%

8 Reps 80%

9 Reps 77%

10 Reps 75%

Understand—these are the MAX repetitions at given percentages. This is all-out, empty-the-tank effort. This is the ceiling. Very rarely should you program these percentages at these rep ranges. Never program over these ranges, because it’s physically impossible. In general, you should be programming significantly lower than these for general working sets (in a later article, I will go into detail about how to program percentages).

4. Heavy Weight, Poor Technique

The goal of the weight room is to get stronger. But focus too much on weight at the expense of technique and you actually limit progress long term. And, get kids hurt. The only reps that should count are reps that are done with excellent technique. Develop technical standards that all of your coaches and athletes understand, then strictly adhere to them.

If you sacrifice technique on a lift in order to load more weight, the athlete is strengthening a poor movement pattern. Poor movement patterns are inferior to good movement patterns at building strength because they move the stress away from the target muscle groups. In the end, your athletes will hit walls that they can’t overcome without a significant regression to fix their technique.

Poor movement patterns are inferior to good movement patterns at building strength because they move the stress away from the target muscle groups, says @DNeill62. Share on X

5. Teaching Olympic Lifts with No Olympic Lifting Background

To Olympic lift, or not to Olympic lift? This seems to be a never-ending controversy in strength & conditioning. While I won’t comment on the benefits and drawbacks of the Olympics lifts, I will say that only coaches who know how to properly teach and perform them need to include them in their program.

Olympic lifts are among the most technically difficult movements you can perform in the weight room and require a trained eye to coach. Including them when you aren’t familiar is a recipe for disaster.

6. Exercise Order

A poor understanding of exercise order can ruin training effects. In general, you should start your training with the most technical lifts (like cleans) and finish with the most physically exhausting lifts. This is because fatigue from one exercise can decrease performance in another. So, if you have a heavy squat session before bench press, bench performance will suffer. However, since bench press isn’t as taxing on the whole body as the squat, heavy bench before squatting is unlikely to affect performance. Technical ability and focus both decrease through fatigue, so you shouldn’t program Olympics and other technical exercises late in a session.

Keep in mind how much soreness and CNS fatigue a session will create when planning your splits. If you lift heavy legs and do conditioning on Monday, you will risk poor output and injury with sprints on Tuesday, says @DNeill62. Share on X

Conditioning before lifting will also decrease your output, so save it until last when possible. If you run gassers before sprint work, then you won’t truly get high-output sprints. Also, keep in mind how much soreness and CNS fatigue a session will create when planning your splits. If you lift heavy legs and do conditioning on Monday, you will risk poor output and injury with sprints on Tuesday.

Fail to Plan, Plan to Fail

Having solid plan for your training cycle is of the utmost important if you are going to see the results you’re looking for with your athletes. We will do a much deeper dive into these areas in later articles, but here is a quick overview of a few key decisions a coach needs to make before a training cycle begins.

Training Splits

How many days are you going to train? What adaptations are you trying to achieve on each day? How can we avoid one day of training interfering with the next?

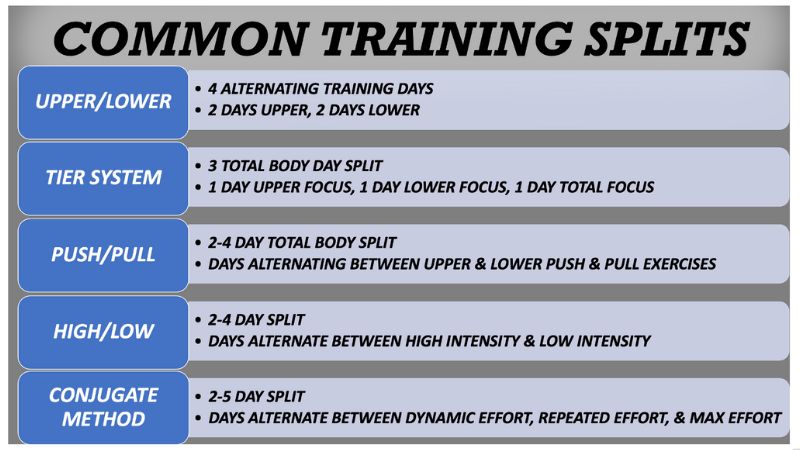

These are important questions when deciding on splits. Training splits answer these questions and determine how the weekly training plan looks. Common training splits are:

- Upper/Lower

- Tier System

- Conjugate Method

- Push/Pull

- High/Low training

I would avoid trying to program bodybuilding-style, body-part splits with athletes.

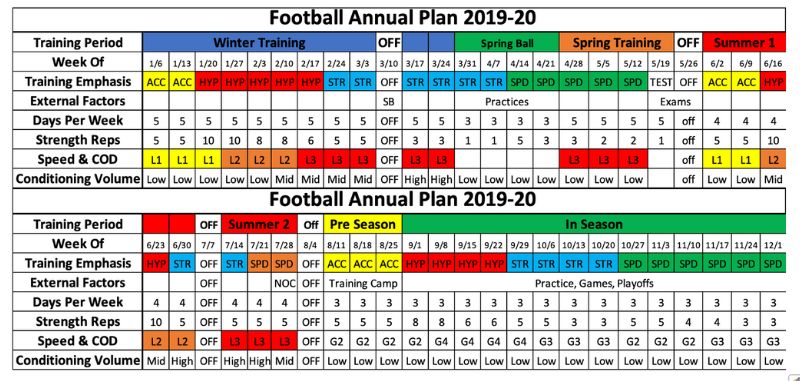

Periodization

In S&C, we operate in small 2-4 week blocks, or microcycles. These cycles allow us to focus on a specific quality as a priority for a period of time before changing up sets, reps, and volume with a new cycle and then chasing a different adaptation.

Often, these are blocked together in an order where one cycle supports the next. For instance, traditional periodization started with a hypertrophy phase to build muscle, then followed with a strength phase to make the new muscle stronger, then finished with a power phase to take that strength and make it explosive. Common periodization models are traditional linear, block periodization, and wave periodization.

Speed, Agility & Conditioning

You want to plan your speed, agility, and conditioning work to progress over time to promote continued adaptation. This might mean increasing conditioning volume, agility complexity, or sprint intensity as a cycle progresses. Always remember to have a goal you are trying to build to at the end of a cycle that supports what you are doing on the field. If you work with baseball players, it doesn’t make sense to build them up to 2–3 mile runs when those efforts look nothing like the energy system demands of the sport.

Preparing to Zoom in

Strength & conditioning is an amazing field; it can, however, have an overwhelming amount of information available on how to develop better athletes. But it doesn’t have to be complicated. A simple, well-designed program that is coached at a high level will transform your athletes.

You don’t need to be an expert to understand the foundational principles of this field, and following best practices will improve your teams while keeping them healthy. As we go through this series, my aim is to provide you with easy-to-understand, foundational concepts so that you can be your best and avoid the pitfalls that so many coaches fall into.