[mashshare]

Brendan Cole, MS, is currently the Start Coach for the United States Bobsled and Skeleton Federation. In 2018, he was part of the training staff that coached the United States Two-Woman team to an Olympic Silver medal. Cole is an accomplished hurdler and represented his home country of Australia at the 2012 Summer Olympics in Rio. He was also part of the Australian 4 x 400 relay team that won the gold medal at the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi. In addition to his role at USA Bobsled, he serves as a head coach, performance therapist, and sprint coach for ALTIS Australia.

Freelap USA: Remote coaching is a difficult part of high performance, especially with Olympic sport. What are some thoughts and considerations that may help all sports become better at managing athletes from afar?

Brendan Cole: Coaching is easy. Coaching well is really hard. Coaching an athlete toward the upper limits of their possible genetic and environmental capacity, at a specified time and place, is one of the most difficult scientific endeavors we face in elite performance.

I have the pleasure of working with three different sports over two different seasons: sliding sports bobsled and skeleton in winter, and track and field in the summer. What is not so pleasurable is the consistent time I spend away from athletes. The winter sports take me around the world for six months of the year, and then I don’t see those athletes, for the most part, until late fall. The opposite happens for the track guys and girls. Not ideal.

While coaching remotely will never replace being physically present, you can make it work more effectively with a few tools and principles, says @Brendan_Cole. Share on XCoaches who can’t be in the same place as the athletes they work with are forced to coach remotely. This can sometimes feel like trying to drive a car while sitting in the backseat, blindfolded. And sometimes even locked in the trunk. It is a challenge, but you can make things easier in a few ways.

Remote coaching removes some of the key aspects of good coaching:

- Real-time feedback to athletes.

- Developing a “coach’s eye” within a 3D context.

- Consistent conversations with athletes, in person, watching for important information from body language and nonverbal communication.

What you are left with is a most challenging task, indeed. Remote coaching at any level encounters the same problems. When I was working at ALTIS, I learned to watch for the enormous amount of information we absorb when present during, and on both ends of, training sessions. Things like athlete posture, interactions with other athletes, movement patterns in warm-up, vocalization of mood, and even practices of hydration and nutrition are all part of the athlete’s web of determinants on any given day.

But for some of us, coaching remotely is still the best option for an athlete. It will never replace being physically present when coaching, but you can make it work more effectively with a few tools and principles.

Freelap USA: You talk about the need for building a foundation through education. Can you explain this process in more detail? It sounds very effective for any level of athlete.

Brendan Cole: Education and understanding are paramount when starting off with a new athlete. Every coach has their own philosophy and coaching methodology, so having the athlete understand those driving forces in a program will set the landscape for development.

I highly recommend having at least 1-2 training blocks with the athlete in person when starting off. You can get a lot done in three weeks. It can save months of time trying to go back and forth with movement literacy and basic pattern establishment.

It is critical to know what windows you will create to see into the athlete’s training and response to load, says @Brendan_Cole. Share on X

Secondly, create a system of feedback. The importance of determining how the athlete will communicate cannot be emphasized enough.

- Spend time with the athlete in the beginning (if at all humanly possible).

- Establish a communication system.

- Educate athletes on your philosophy and methodology.

It is so critical to know what windows you will create to see into the athlete’s training and response to load. I like to write objectives for each block and share them with the athlete. Knowing the training goals for the sessions and what they can expect goes a long way in their understanding of your “why.”

Freelap USA: Can you share how you find strategies around shortcomings with travel and heavy volume during a season? Monitoring and constant communication seem like the name of the game with athletes who travel internationally.

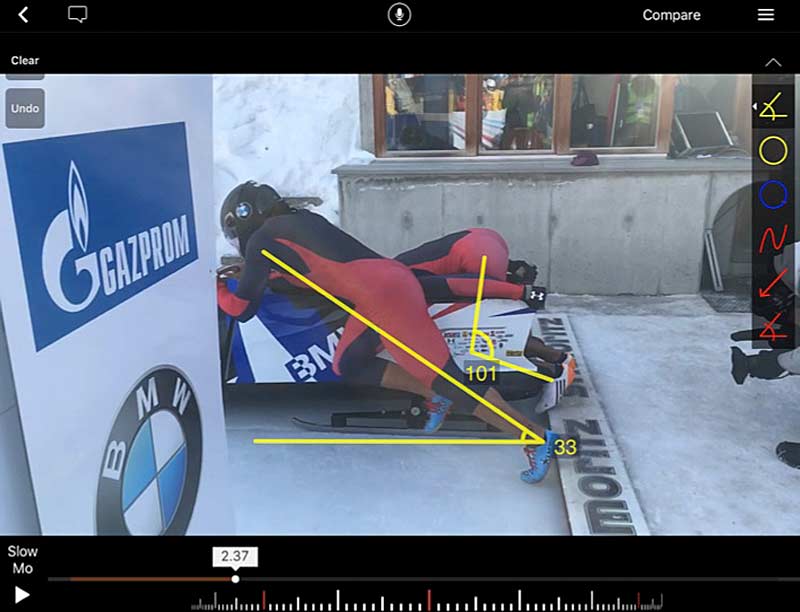

Brendan Cole: Losing the ability to be physically present as a coach requires some creative solutions to make up for the lack of interaction. Using film and monitoring data will help with this. I use video feedback, and it has been invaluable. The athletes can use the app to record and then just “tag” me in the video to send it through. I can then record voice over the video during playback, incorporate basic tools of kinematic analysis as feedback, then send it back. It is obviously not “real time,” but it is really helpful for getting information back to the athletes.

- Find a good system for feedback and monitoring.

- Communicate whenever possible.

- Pay attention to what you have.

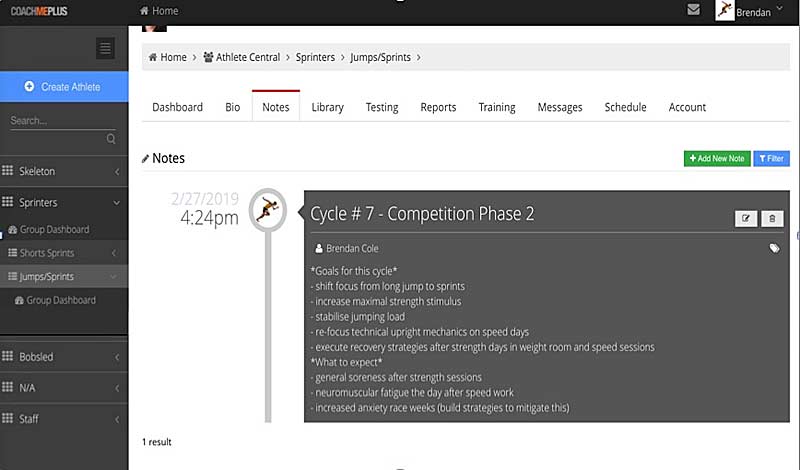

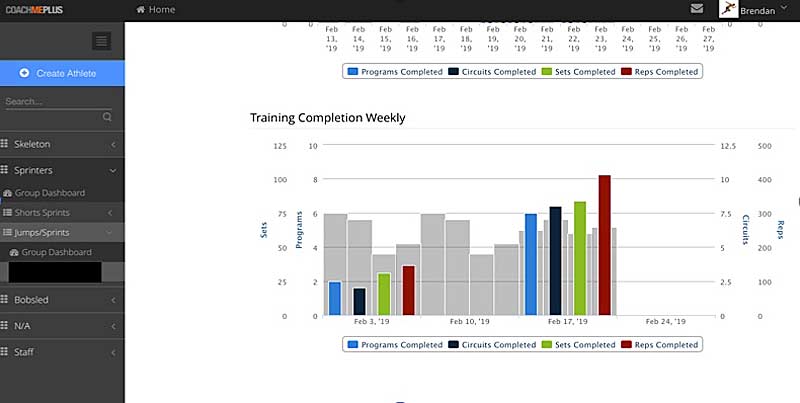

On the monitoring and communication side, I started using the CoachMePlus app to program, monitor, and communicate with the athlete. This has been a game changer for me, with all features in one app. I set up a version of the Hooper Mackinnon Questionnaire (1991), and it gives me consistent insight into the athlete’s well-being and training. It also maps things out for me with projected volume of training to help with periodizing and long-term planning.

There are many systems and programs that are able to do this, and I previously just used a Google doc or Excel spreadsheet. Compliance is always the issue with this, as well as time spent on such a project. I have been really happy with the app so far, and the athletes I work with have given great feedback on its usability. It has saved time and increased compliance.

As with all monitoring, it is useless unless you are paying attention. Sometimes the numbers show hidden insights that are not perceivable to the athlete, or even to a coach who is present. The more consistent you are with monitoring and trying to find relationships between variables and performance, and the longer you do it for, the better you can coach. Other lifestyle factors such as study, work, and personal relationships can show up in an athlete’s mood changes and readiness to train. These are underestimated variables in the athlete’s progress and adaptation.

Freelap USA: Having a plan is everything, but the ability to adjust is important. Can you share with coaches how you balance having a road map with knowing when to take a different path? Perhaps getting into Dan Pfaff’s three-day rollover concept?

Brendan Cole: Moving from a professional track athlete into working with winter sports has given me a great appreciation for the amount of work that goes into sports like bobsled and skeleton. On tour, the athletes have to prepare sleds, move their own equipment, help others do the same when they are not sliding, sleep in small dorms with other athletes, train in frigid cold garages and parking lots, and move a completely mobile garage—every week. On top of this, the athletes often don’t know if they are competing on the weekend until only days before. If I had not seen all this and the impact on the athletes in person, I am sure that I would do a horrible job at programming for them. Having a plan is necessary, but being able to change from week to week is a key adaptation for training programs.

- Understand the athlete’s environment.

- Set boundaries for adapting programs.

I use Dan Pfaff’s “3-Day Rollover” structure for this. It is a simple strategy of identifying the key sessions that need to be completed, and then plugging them into the week when you can. For your athlete’s three sessions, you might be able to complete them twice in a week (if everything is going perfectly). If travel, fatigue, illness, or lack of training facilities heavily impact the athlete, you may need two, or even three weeks to get through the three sessions of quality work.

Dan often tells the story of Olympic champion Greg Rutherford doing one high-quality speed workout every three weeks. That took a lot of trial and error, and a very good coach to recognize this, but the result was a very injury-prone athlete reaching the pinnacle of his career at the right time.

Freelap USA: Building a network or team around an athlete seems like a real challenge, even today with so many resources. Can you outline the steps of building a high-performance team?

Brendan Cole: Most importantly:

- Find appropriate sports medicine support.

- Understand the “threats” of training alone.

The benefits of the support team around an athlete cannot be underestimated. I will talk a lot about physical therapy (massage, chiro, physio etc.), but the team around an athlete can include anyone from a psychiatrist to a nutritionist. Even within the well-funded high-performance institutes where I have worked, the engagement of these support staff directly affects the outcome of your programming and the success of the athlete. Just having access is often not enough. I have seen athletes getting physio treatment multiple times a day with very little change in the direction of treatments and, consequently, very little change in the outcome. A lazy practitioner is about as effective as a warm shower, and this is why your athletes need to find the right people.

The benefits of the support team around an athlete cannot be underestimated, says @Brendan_Cole. Share on XA mentor of mine, and training theory wizard—Dan Pfaff—often breaks down injuries (and lack of performance) into four different categories.

- Programming

- Lifestyle

- Biomechanics

- Therapy

As a remote coach, programming is all you. You will probably have less impact on lifestyle and biomechanics (if you are not attending all sessions), but for the most part, therapy is out of your control. This puts a large weight on communication with those in the network, and on the quality of the therapy. Finding great therapists is not easy and does require some work. Sometimes the athlete will already have a great therapist they work with, which will help you out a lot.

Here are some important questions that relate to the three aspects of a good therapist: engagement, knowledge, and skill.

- How well does the therapist communicate what they are doing, and why?

- Is the therapist willing to have consistent communication with you when they see the athlete? What is their notation system, and will they share their treatments with you?

- Do they work with other athletes? Which ones?

- What are their philosophies on other modalities/ideas?

- Can you get feedback from other athletes on their experience?

These are just some ideas. But if you ask good, probing questions, you should soon find out at least how appropriate a therapist could be. You will not be able to determine their skill level over the phone, but their willingness to help, engagement in the goals of the athlete, and knowledge will guide you.

Other examples inside a support team are:

- Sport psychologist

- Nutritionist

- Mentor (in life or in sport)

- Strength and conditioning specialist

- Physiologist

- Psychiatrist

- Training partners

- Parents/family/partners

I have talked mostly about therapy here, as I see it as highest in priority. But knowing as much as you can about the “threats” to success for an athlete will guide you in putting together a winning team. This awareness will come from your own analysis of what has worked in the past, what has not, and, most importantly, feedback from the athlete.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]