Performance attributes are measured in many ways. In every industry, key performance indicators (KPIs) are all the buzz.

In strength and conditioning (S&C), we commonly use KPIs from sprint times, shuttles, jumps, benches, squats, deadlifts, and other exercises. Are we missing the point of using highly skilled exercises to predict athlete performance?

Utilizing physics and Newton’s 2nd Law may be the simplest way to evaluate an athlete. According to Joel Jamieson, sports can be broken down into three main components:

- Performance

- Skill

- Tactical

Coaches need to start bridging the gap between performance and skill training components. S&C coaches spend most of their time facilitating performance components, while sports coaches primarily focus on skill and tactical components. For sports coaches, this includes the scheme and strategies they plan to use in competition.

In football, these elements are used to create an advantage or negate one, taking numbers, vectors, and relative space into consideration. An easy way to think about the modern game of football is that the offense’s goal is to create space, while the defense’s goal is to take away space. S&C coaches are tasked with increasing their athlete’s performance-related attributes, such as power.

An easy way to think about the modern game of football is that the offense’s goal is to create space, while the defense’s goal is to take away space, says @CoachBubsMartin. Share on XIn football, power wins—it is so highly regarded that at the core of the game is the run concept called “Power.” For that reason, I will break down key blocking responsibilities in that Power play later in the article. I will provide specific movement techniques and vectors as examples of how the three components of sports connect in training.

In physics, power (P) is the product of force and velocity or mass, acceleration, and velocity. Ultimately, we work to produce large amounts of force at a rapid rate and in the most efficient angle possible. At MVP Academy, we use the following terms:

- Force Production—High ground contact times

- Rate of Force Production—Low ground contact times

- Force Application Angles—Vectors

Force Production

Newton’s 2nd Law tells us that Force = Mass x Acceleration. In the weight room, we increase force production over time through one of two methods: increasing load (increase in mass) or increasing how fast we move a given load (increase in acceleration). This can be perceived as the “S” portion of the “S&C” in our field.

An absurd number of methodologies have proven to increase strength. I’d say that most S&C coaches are effective with this prescription. We will leave the “my kung fu is better than your kung fu” discussions for the bird app.

On the field, high-force production events are seen in high accelerations, decelerations, and impacts. These movements require longer contact times to produce these higher outputs of force. When training on the field, we simply “slow the athlete down” by adding some form of resistance or opposing motion. This may be in the form of sled towing, pushes, hills, bands, or various other methods. Intensive plyometrics, jumping for maximum height or distance, and resisted or loaded jumps are other prescription methods that help increase force production.

Rate of Force Production

To increase the rate at which force is produced, we aim to “speed the athlete up.” In the weight room, we can move a very light load faster—increasing the number of reps in a short, specific amount of time—or prescribe assisted movements with bands, etc. We want to prescribe movements requiring shorter ground contact times and minimize the time in which we produce a given force.

How hard we push is not the goal. We want to get the load away from our torso or get off the ground as fast as possible: the floor is lava. Extensive plyometrics and assisted jumps with bands are methods we can use to increase the rate at which athletes produce force.

On the field, there is no better way to train an athlete to increase their force production and stride frequency rate than maximum velocity training. The fastest a human can move their body is by sprinting and achieving maximum velocity. The best method to do that is with flying sprints.

We tell our athletes constantly, “Want to get fast? Run FAST! Want to stay fast? Run fast consistently!” Once our athletes have progressed to maximum velocity drills, we do at least three reps of flying 10s a week, with either a 20-yard or 30-yard build-up. We prefer to use a 30-yard build-up in our athletes because they just don’t yet have the acceleration capabilities to hit maximal speeds in 20 yards. These end up being full sprints for 30 yards, which defeats our intent of limiting load by doing minimal reps of flying 10s.

Force Application Angles

The closest distance between two points is a straight line. When athletes learn how to create good angles, they can efficiently use the forces they produce. An easy way to teach this is with vectors. At the NHSSCA National Conference in Nashville, Tennessee, Bobby Stroupe described how he teaches his vector system.

When athletes learn how to create good angles, they can efficiently use the forces they produce, says @CoachBubsMartin. Share on XThere are eight basic vectors. We can use the navigational directions as a guide; imagine facing north, going clockwise.

- North = 0°

- Northeast = 45° (right)

- East = 90° (right)

- Southeast = 135° (right)

- South = 180°

- Southwest = 135° (left)

- West = 90° (left)

- Northwest = 45° (left)

Movement Patterns on the Field of Play

Sport is played at a speed set by the athletes on the field. They must play at this speed to perform skill-related tasks during play. Increasing linear speed just for the sake of running a fast 40 or any other exercise-driven event misses the point. The goal is to be good at sports.

Becoming fast enables an athlete to play at game speed at a lower relative intensity. In the game of football, the idea is to get fast so we can play slow. An athlete needs to stay under control and move efficiently to get into the positions and postures to make plays.

Becoming fast enables an athlete to play at game speed at a lower relative intensity. In the game of football, the idea is to get fast so we can play slow, says @CoachBubsMartin. Share on XOn average, football is played between 12 mph and 16 mph, as noted by Tony Villani. This is clearly a submaximal velocity. One needs to be able to get to a spot in an effective position and posture to make a play. As a longtime sports coach, I genuinely feel S&C coaches can provide immeasurable value by bridging performance and skill through coaching movement patterns.

Lee Taft defines his 7 Fundamental Movement Patterns in Athletics as:

- Linear acceleration

- Linear max velocity

- Lateral shuffle

- Lateral run/Crossover

- Backpedal

- Jumping

- Hip turns/Flips (transitional)

We want to utilize slower movement patterns before we get into linear acceleration and, eventually, maximum velocity. Maximum velocity, by the way, is rarely reached in sports. Removing jumps and hip turns/flips, we can rank the movement patterns from slow to fast:

- Lateral shuffle

- Backpedal

- Lateral run/Crossover

- Linear acceleration

- Max velocity

The faster athletes move, the harder it is to change directions and transition between movement patterns. Transitions between movement patterns and changing directions must occur when an athlete’s foot is on the ground. This foot must produce force in the opposite direction of motion to decelerate, accelerate, and/or set up changes of direction. Teaching this fundamental concept helps train the athlete on foot placement and orientation.

Video 1. Each lineman can need to apply a different movement pattern when executing a given play.

TASKR

We currently use the acronym TASKR to deliver and teach our tactical scheme to the football athletes on our team. We define TASKR as:

-

T – Technique. How we perform a specific task.

A – Alignment. Where one lines up on the field of play.

S – Stance. Related to the positions and postures the athletes should be in when the ball is snapped.

K – Key. This is where an athlete’s eyes are. Typically, it’s the near hip of our target/assignment. This creates a high level of eye discipline. It helps us gather data before, during, and after each play, enabling informed decision-making as the game progresses.

R – Responsibility. This defines each individual’s task or job. Any given play’s call will dictate an athlete’s responsibility, which may revise their T-A-S-K above.

How do we connect the dots between performance, skill, and tactical strategies to help our athletes succeed on the field? Let’s break down the Power of an 11-personnel offense versus a 4–2 over front (Nickel) defense. This is an early install in nearly every modern offense’s offseason.

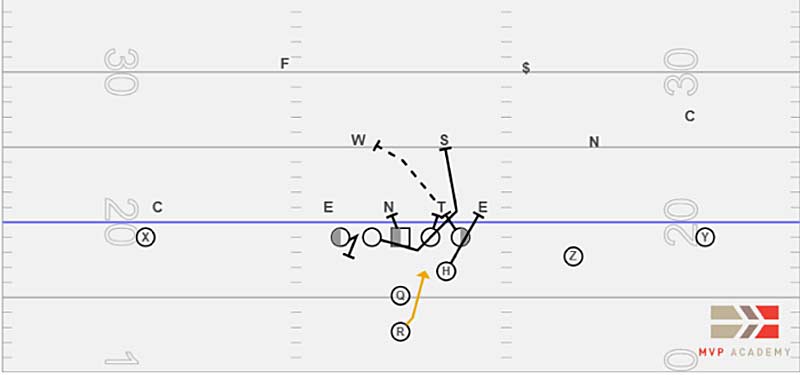

We only focus on the six blockers tasked to block the six defenders in what is called “the box.” The goal is to create space (another gap, C) between the playside defensive tackle (T on the right) and end (E on the right), so the backside (L) offensive guard can wrap to block the playside middle linebacker (S).

The ball carrier (R*) will follow this guard through that gap (C*) created. The center down/back blocks on the backside defensive tackle (N on the left), and the backside tackle performs a hinge technique to protect any penetration into the gap created by the vacating guard and then looks backside, which is detailed below. In summary, this is the tactical strategy of running the play known as Power.

Image 1. A breakdown highlighting roles and responsibilities in Wisconsin’s version of “Power” available here from Dustin Michelson of ChampionshipProductions.com.

Every player involved in this play requires the skill levels to perform the Technique (T) originating from their Alignment (A) and Stance (S) while maintaining eye discipline on their Key (K) to execute their given Responsibility (R*).

Kickout Technique: H-Back

The H-back, generally called a wing in this alignment, is typically lined up somewhere behind and between the playside guard and tackle. He is tasked to “Kick” block out the playside End (E). The goal is to create as much space as possible between himself and the offensive tackle.

From his alignment, he pushes off his inside foot (left) and heads at an angle to stay inside of the E. The E is taught to squeeze the down double-team block that the tackle is performing. He must aim somewhere right of the tackle’s outside hip. With his eyes on the inside edge (hip), he must attack his opponent with leverage and high force. We utilize an angled shuffle with the near (right) foot up to strike the inside (right) half of our opponent.

Hinge Technique: Backside Tackle (Left in Diagram Above)

The backside offensive tackle is tasked with performing what is commonly called a “Hinge” technique. Pre-snap, his eyes will be on the backside middle backer (W), looking for him to blitz. Out of his staggered stance—right foot forward in this example—he will perform a quick shuffle to his right by pushing off the inside of his left foot. If the W does NOT threaten him, he will perform a hip flip at approximately 45° to his left and transition into what’s most likely a shuffle to his left to block the backside end (E on left). This E will most likely be squeezing his left hip and attacking his left/outside edge because our tackle’s movement indicates a down block initially.

Wrap Technique: Backside Guard

The backside guard is tasked with performing what’s called a “Wrap” technique to the playside middle linebacker (S). There are multiple ways to perform this technique. We utilize a lateral POP start, push-open-push, into a crossover/lateral run.

The guard is taught to push with great force off his backside foot (left), which is outside and back in his staggered stance. Then he opens his front side with his foot pointed at an angle between 45° and 90° to the playside (right). Now he crosses over with his backside foot/left in the front to perform a lateral run/crossover while keeping his eyes on his target and chest square to the line of scrimmage. His goal is to clear the double-team block performed by his teammates on the playside guard and tackle with the least amount of space possible between them and himself. Once he clears, he climbs vertically to his target, S.

Down/Back Block Technique: Center

Penetration by the interior defensive lineman will destroy any run play, especially by the backside tackle versus Power. Any penetration risks the wrapping guard being disrupted on his path, which increases the chances of freeing up the playside middle linebacker. The center’s job is to eliminate penetration by cutting the defender’s path off. He must take an angle, sometimes lateral, by pushing off his playside foot.

Some centers prefer a lateral shuffle. Positioning on the defender is more important than “blowing the guy up,” in this case. The goal is to keep the defender on the backside of the center while preventing any upfield penetration.

Apex Double-Team, Post and Gallup Technique(s): Playside Guard & Tackle

“Power is not the guard wrapping to the front-side backer. It is our ability to create movement with our front side double team to the backside backer.” – Brennen Carvalho (Center), Kaua’i native and professional football athlete

The apex double-team block on the playside of Power is the play’s most critical component. The offense’s playside guard and tackle must work in unison to move the three-technique off his spot. Ideally, they want to move him onto the lap of the backside middle linebacker.

The playside guard is commonly referred to as “the postman.” His initial assignment is similar to the center’s but on the playside. The guard must prevent any upfield penetration by the three-technique by beating him to the “spot.” The guard will push off his backside foot and attack his man by aiming to get his playside foot into the crotch of the defender.

Meanwhile, his partner, the tackle, will perform a gallop technique. Essentially, this is an angled shuffle. The tackle aims his gallop (angle shuffle) with the goal of getting the playside foot into the crotch of the defender and violently banging his hip. We want to drive through the hip of the defender to move him to the backside of the guard. The guard will take over the block by positioning himself on the playside of the three-technique, freeing up the tackle to go and block the backside middle linebacker. Ideally, the tackle wants to stay on the playside of the backside middle linebacker.

Reverse Engineering

There’s an advantage in having the ability to reverse-engineer strategies, plays, or schemes and then implement drills to build skills and the physical performance attributes needed, says @CoachBubsMartin. Share on XThe intent of this article is to share how bridging the gap between performance, skill, and tactical strategy benefits athletics. For any team, there’s an advantage in having the ability to reverse-engineer strategies, plays, or schemes and then implement drills to build skills and the physical performance attributes needed to execute these skills and strategies. This integration enhances the value of coaches and the athletes involved.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF