“You’ve been brought up a certain way since high school. It’s ingrained in you. I had a wife. I had a family. A business I was starting. But I kept hearing those little things in the back of my mind: you’re letting your team down.”

Joe Jacoby, a former All-Pro and three-time Super Bowl champion, anchored the Washington Redskins’ infamous “Hogs” offensive line through a tremendous 13-year career in the ’80s and ’90s. In the latter stretch of his career, while brushing his teeth one morning, the offensive tackle collapsed on his bathroom floor with debilitating back pain. Widely regarded as one of the tougher guys ever to play the game, Jacoby would be in the lineup that same week for the Redskins, despite his crippling physical state and the obvious risk it would pose.

The result?

He was hospitalized for three days after that game. Shot up with cortisone and painkillers, discharged, and then—you guessed it—back on the field with his teammates for practice within another day or so.

The toughness of professional athletes is unmistakable, and perhaps this is most glorified in the NFL, where a penchant for unrelenting aggression and channeled violence are all but a prerequisite for professional football players. Truth be told, the story of Joe Jacoby—his toughness, durability, and borderline-reckless willingness to sacrifice “for the team”—is hardly uncommon among NFL players. Bear in mind, these earlier years of professional football, in particular, had a much different brutality to them, as player safety and sustainability weren’t exactly priority items.

Take Jim Otto, who, now at 85 years old, may be the figurehead of “football toughness.” A Hall of Fame center who played 15 seasons for the Raiders, Otto was a pioneer in that early, brutal era of the NFL. Famously, Jim Otto has had upwards of 75 surgeries to amend the injuries he sustained throughout his career.4 This includes 28 knee operations, an unknown number of concussions, and three life-threatening infections, culminating with having his lower right leg amputated in 2007 due to complications from previous surgeries.1 And knowing what he knows now, after suffering through so many injuries and surgeries, would he do anything differently if he could go back and do it all again? “Absolutely not; pain and injuries are a part of what I signed up for.”

The average NFL career lasts a mere 3–4 years, but that brevity doesn’t prevent these athletes from suffering the long-term consequences of their careers, says @d@danny_ruderock. Share on XBecoming a professional athlete is the fairytale dream for millions of kids around the world, and one that very rarely materializes into a reality—only about ~0.0075% of high school athletes reach professional levels.2 In other words, statistically speaking, an individual has about the same odds of being struck by lightning twice as they do of becoming a professional athlete. There is an incomprehensible amount of work, talent, timing, and opportunity needed to reach the pros. But for all that goes into getting there, holding on to it proves even more fleeting for the majority of NFL athletes, as the average career lasts a mere 3–4 years. Despite this reality, you would be hard-pressed to find any current player who feels they won’t defy those statistics.

That brevity doesn’t prevent these athletes from suffering the long-term consequences of their careers. This is something I’ve continued to learn vicariously through my time working with Brett Bech, a 51-year-old former NFL wide receiver. Brett has spent an extensive amount of time at the NFL level and is one of few to do so as both a player (five years) and strength and conditioning coach (13 years). This has also allowed him to see and experience the game through multiple lenses.

Brett sustained a relatively “standard” five to six significant injuries throughout his career that, in some capacity, have caused him pain or limited function (of note: his golf game!). As he has described it to me, the pain is just “something you deal with.” Like most, he adheres to the unwritten standard of the NFL world: never show weakness and never complain.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) and Orthopedic Injuries

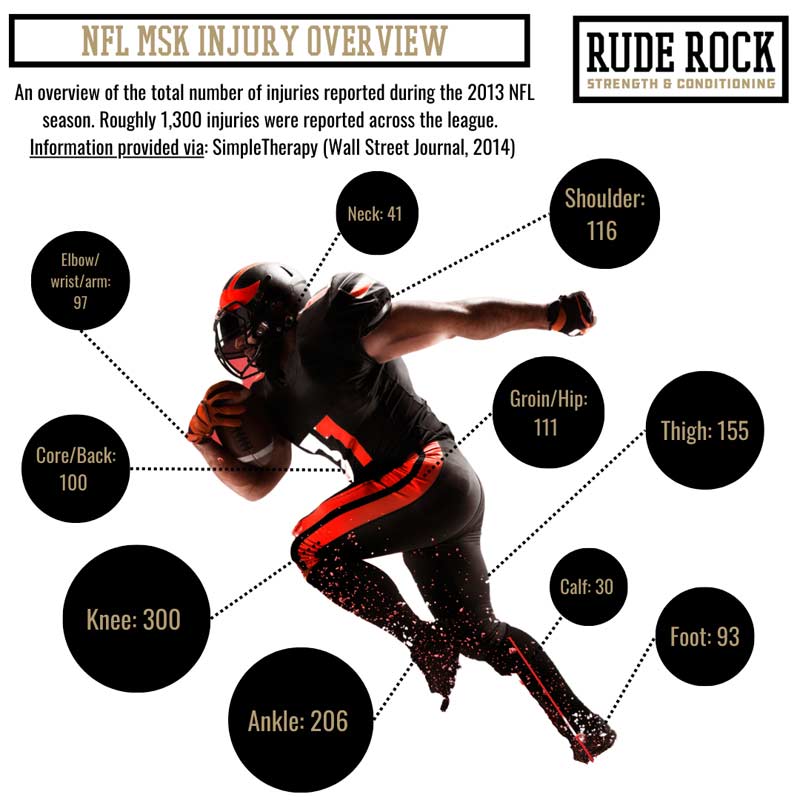

The NFL’s injury rates and types are wide-reaching but have some patterns and commonalities. It is important to consider how injury data has shaped and shifted throughout the evolutions of the game. Since the forming of the “modern” NFL, when the league merged with the AFL in 1966, a lot has transpired to bring the league to where it is today. The rules and structure of the game, dimensions of the field, player size/speed/skill, and emphasis placed on protecting the athletes have all evolved in their own ways. This helps us understand the context of injuries and also allows us to appreciate the efforts that have been put in place.

Not all that has evolved has been for the better, however, as some of the outcomes of evolution have led to questionable decision-making by league officials. The increased volume of play, greater travel demands, and bias of revenue over player may all be factors in how some injuries have occurred in the modern era. Nevertheless, the predominant orthopedic injuries among NFL athletes include shoulder, spine, ankle/foot, and, most prominently, knee injuries.

The increased volume of play, greater travel demands, and bias of revenue over player may all be factors in how some injuries have occurred in the modern era, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XWhile acute orthopedic injuries don’t occur often, they are invariably severe when they do (i.e., leg fracture, shoulder subluxation). Chronic conditions like arthritis, on the other hand, are more common, as they develop from microtrauma over time. The most common soft tissue injuries generally include rotator cuff, Achilles, and hamstring injuries. Soft tissue injuries are a combination of severe/acute injuries (i.e., ACL, Achilles rupture) and chronic deterioration, such as tendonitis and myofascial pain syndrome.

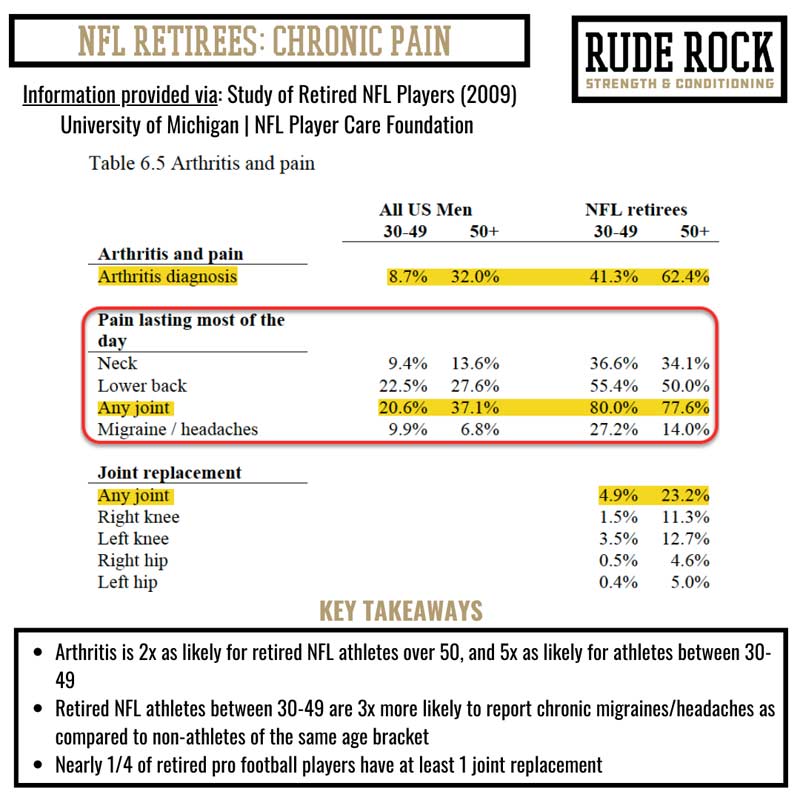

While a select handful of professional football players do walk away relatively unscathed, the vast majority of NFL retirees report struggling with pain and consequential outcomes from injuries/surgeries sustained throughout their careers. Additionally, while a few players are afforded the ability to walk away on their own terms, countless others are ultimately forced out due to overwhelming pain and injuries.

While some pro football players walk away relatively unscathed, a majority of NFL retirees report struggling with pain & consequential outcomes from injuries/surgeries sustained during their careers. Share on XAccording to the University of Michigan 2009 study analyzing retired NFL athletes, 80% of NFL retirees aged 30–49 and 77.6% aged 50 and older reported having daily joint pain. Comparing these percentages to the average U.S. male, whose values are substantially lower—20.6% less than 50 years old and 37% over 50—really puts things into perspective. Based on this data, NFL retirees under 50 are nearly four times more likely to report chronic pain. As we could assume, NFL retirees also report having an arthritis diagnosis at a staggering rate. More than 60% of NFL retirees over 50 and 41% under 50 indicated having at least one arthritic joint.4

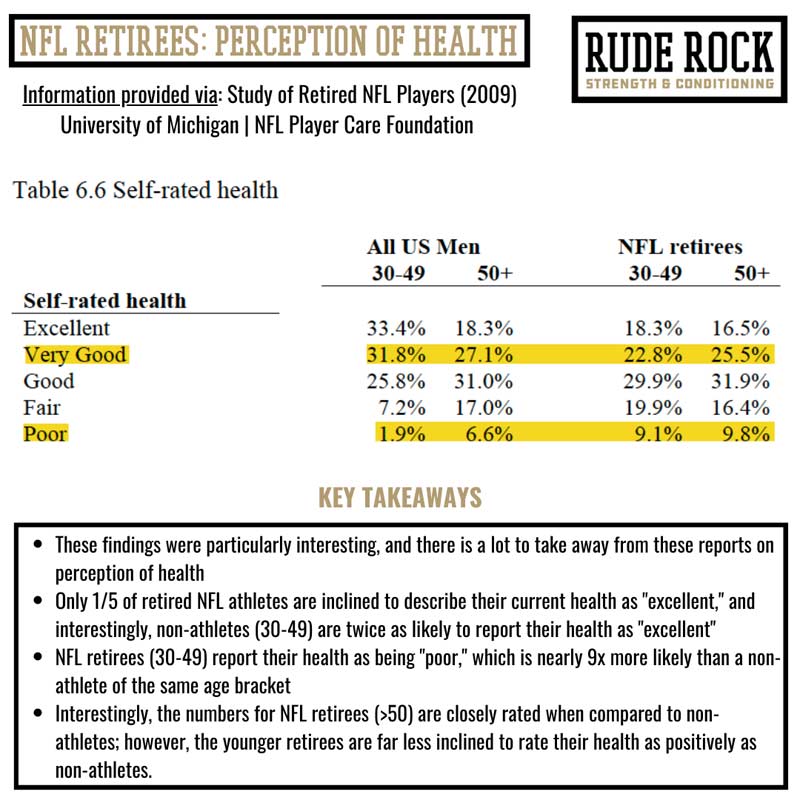

I alluded above to how the presence of pain and injury can adversely affect an individual’s state of anxiety and depression, and this is not something to overlook. Whether transient or symptomatic, states of depression and anxiety have indirect influences elsewhere on the body (e.g., the immune system) and can also be damaging to perception, confidence, and even self-worth. When size, strength, skill, and function begin to deteriorate, it is often a sobering reality for individuals who were once world-class athletes.

As demonstrated in the graphic below,4 NFL retirees appear to have consistently lower ratings of personal health compared to the average adult male. While there is a relativity to this that needs to be recognized, this survey indicates that most retired NFL players, both under and over 50 years old, perceive their health as being either good, fair, or poor, as opposed to very good or excellent. This was slightly more pronounced in the under-50 group, as 58% of respondents collectively reported good or worse.

Head and Brain Injuries

Beyond the musculoskeletal and orthopedic injuries—and perhaps even more significant—is the rate of head injuries and long-term effects on the brain. The violent nature of football makes the potential for head injury unavoidable, no matter the extent to which we try to modify the game and protect the players. There has been a meteoric rise in data surrounding concussions and brain injuries, particularly regarding NFL athletes.

The discussion around head injuries in pro athletes is elusive and often muddled with bureaucracy and litigious debates; consequently, we ignore the human element, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XHowever, the discussion around head injuries in pro athletes is elusive and often muddled with bureaucracy and litigious debates; consequently, we ignore the human element of this discussion. Nevertheless, all concussions are not created equal and, like most injuries, affect people differently. This includes the long-term effects of concussions, which are highly variable as well.

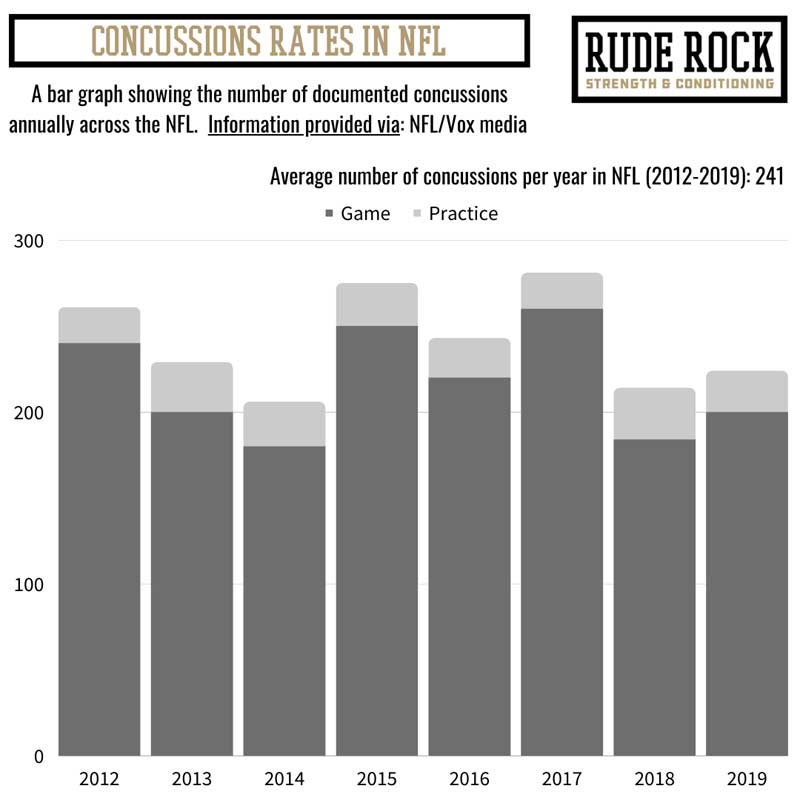

As such, an eight-year data set (2012–2019) shows roughly 240 documented concussions throughout an NFL season, correlating to about 10% of all NFL players.5 As evidenced in the graphic below, the majority of concussions occur during game play, as opposed to practice. This may seem logical, but it is an important indicator of how improving player care and safety has benefited athletes. The average NFL practice in the Jim Otto and Joe Jacoby days was typically much more contact-intensive.

A concussion rate of 10% may not seem staggering, but there’s a lot to unpack here. First, 10% of all active players on each roster may not accurately reflect the risk, as at least half of an active roster doesn’t see much playing time. Then we have the efficacy of reporting, both from the player and the team; despite recent improvements, this has been questionable, at best, for decades. This data also does not represent what the long-term consequences may include, which can be debilitating.

Along with concussions, we also have CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a severe condition that causes rapid degeneration of brain tissue. Although this has been a contentious and wildly publicized discourse, over the last 10 years, we have seen a rise in CTE studies and findings that, quite frankly, have almost unanimously produced harrowing results. For instance, Boston University’s CTE Center reported that this number might be as high as 90%–95% of all former players.6 Additionally, NFL retirees are at a much higher risk for cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer’s, dementia, ALS, and chronic progressive memory loss and cognition4 than the average adult male.

Underlying Health and Wellness

The final element to consider here is the effects on cardiovascular and metabolic health, which may be the “sleeper cell” of the group. The musculoskeletal injuries and, to an even greater extent, the head injuries are very visible outcomes of professional sports. What’s less observable, at least in most cases, is the adverse health effects plaguing former professional athletes.

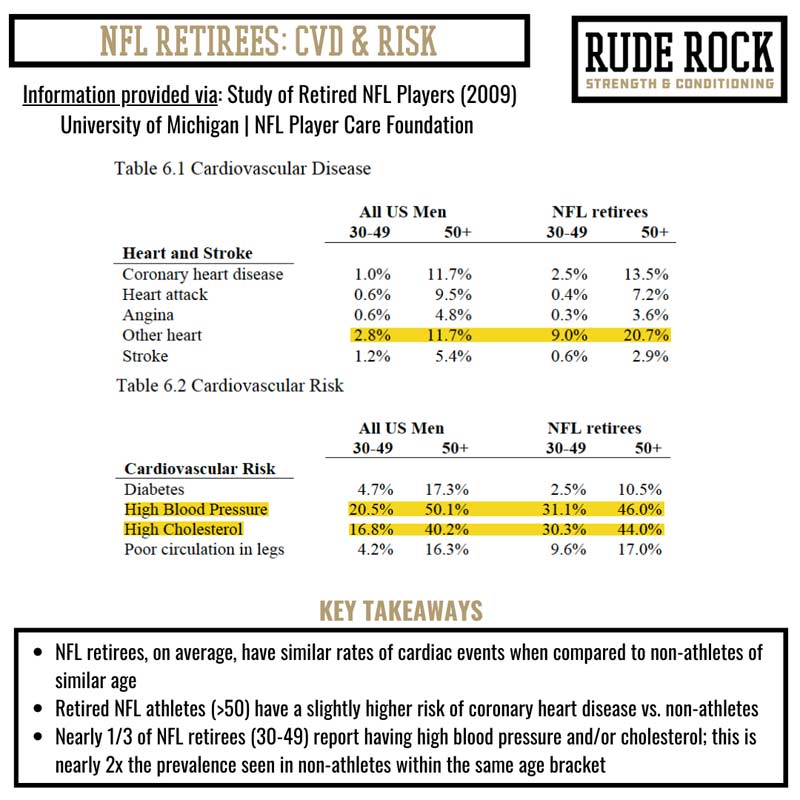

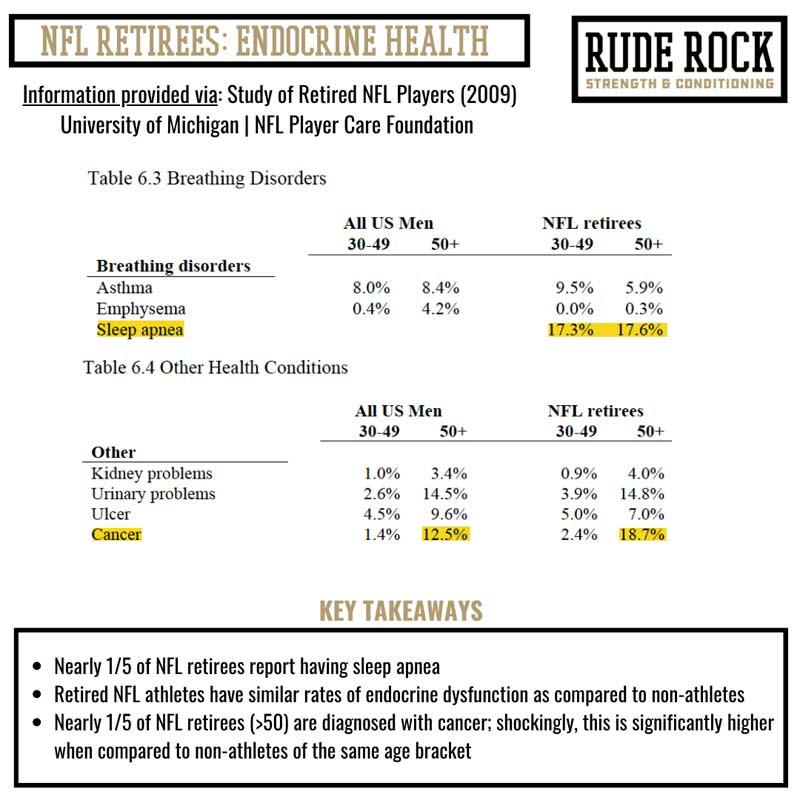

As evidenced by the graphic below, cardiovascular disease, metabolic impairments, and endocrine irregularities are considerable consequences for NFL retirees, affecting nearly half of the athletes surveyed in this study. What is particularly concerning about these data points is the rates at which we see things like heart complications or high BP/cholesterol for NFL retirees under 50 compared to the average American adult.

A common sentiment among former NFL athletes is that they feel like they “live in a body that they don’t even recognize,” often reporting that their body feels much older than their biological age should suggest. This corresponds to the points above on the perception of health. While physical trauma and mechanical damage certainly play a prominent role in this, the general health, wellness, and stress management maintained throughout a player’s career are likely far more impactful on their overall physical state post-career.

For some NFL retirees, the cardiac, endocrine, and nervous systems (among others) may warrant equal or greater attention than mechanical ailments, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XThe accumulative outcome of the unforgiving physical demands of the game, poor lifestyle/health habits, and immeasurable stress and pressures ultimately take a toll on the internal systems. For some NFL retirees, the cardiac, endocrine, and nervous systems (among others) may warrant equal or greater attention than mechanical ailments.

Long-Term Help for Players

The enduring path of a professional football athlete is something few will ever know. Despite millions of fans worldwide tuning in every Sunday to witness the brutality and risk, almost none will understand what it took for those athletes to get there or the arduous route many must take on the other side. The data underscores what we all witness: the compounding effects of decades of training, practice, and competition have consequences on the body—an “orthopedic cost” of sorts.

While the league (NFL/NFLPA) has improved the resources and efforts for assisting its players in their transitional process, it wouldn’t be a reach to say it has put long-term player health on the back burner for far too long. It remains evident that there is a tremendous void of services and organizations designed to help this community of players.

There has always been an immense amount of time, money, and resources funneled into player scouting, development, and maintenance. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for players on their way out of the league, despite approaching an impending lifetime of hurt. Much like we have seen with military veterans over the years, when you can provide value, you’re treated with the utmost priority. But once that value has diminished or become vacant, you’re expeditiously shown the door so that room can be made for the next person up. That needs to change.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

3. Holstein, JA. Jones, RS. Koonce Jr., GE. 2015. Is there life after football? Surviving the NFL. New York, NY. New York University Press.

4. National Football League Player Foundation Care: Study of Retired NFL Players (2009) via the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.