In the short hurdle events, all athletes perform a similar step pattern. The athlete who covers these steps the quickest will always win. Oversimplified, yes, but this concept reinforces the need for technical proficiency and proper race modeling. Along with quick coverage of the predetermined step patterns, accomplished hurdlers minimize airtime to the lowest acceptable duration for efficient hurdle clearance.

As I progressed in coaching and researching the short hurdles, a short list of “must-haves” quickly surfaced that allowed the best chance of a successful hurdle race. Note that these are not my own findings—I made this list from the wealth of existing hurdle research and based it off the work of great coaches and athletes, both past and present.

As I progressed in coaching and researching the short hurdles, a short list of “must-haves” quickly surfaced that allowed the best chance of a successful hurdle race, says @ChrisParno. Share on XMy five must-haves in building the technical model for short hurdlers are:

- Proper accelerative rhythm to manage step pattern to the first hurdle.

- Achievement of intended take-off (TO) distance from the first hurdle (and all subsequent hurdles).

- Displacement of the hips at takeoff to set up the ideal parabolic path over the hurdle.

- Active technique over the top of the hurdle (imposing back to the track).

- Upright body position/front-side stride movement.

The must-haves making up the technical model are only a piece of the puzzle to becoming a successful hurdler. I’d be remiss if I didn’t include the need for psychological/competitive drive, proper training/strength levels, and balanced biomotor abilities. I will break down the must-haves for a technical model throughout the article and the subsequent drilling options needed to achieve these desired traits.

Breaking Down the Hurdle Must-Haves

The concept of “hurdle drills” looks different depending on who is asked. The need for a common definition will help frame the future points of this article. A drill is an exercise or planned movement with the desired goal of improving any single aspect of the hurdle movement for the betterment of the technical model. This doesn’t mean that all athletes hurdle the same or need the same drills—there will always be individualization.

Ultimately, the hurdle coach must have a large toolbox and an understanding of the goal of each drill in order to address any issue within their athlete. Each coach will have their own “everyday” drill sequence within the warm-up and, hopefully, another set to help diagnose and fix issues as they arise.

Proper Accelerative Rhythm

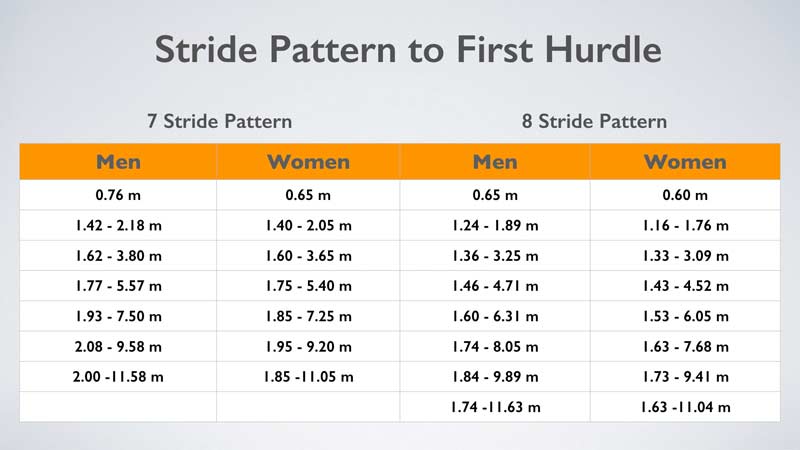

The hurdle start covers a predetermined number of steps at high velocity striving for a proper takeoff into hurdle 1. This must be talked about, rehearsed, and stabilized over time. Most male hurdlers at the high school and college levels take eight steps to the first hurdle. When the velocity being created overcomes the ability to productively use an eight-step approach, the athlete may move to a seven-step approach.

Seven steps affords more space to create (push) the highest velocity possible, although the rhythm will change drastically. Taller athletes, or athletes with a longer trochanter length (TL), may also find the seven-step approach more beneficial. No matter the selected starting step pattern, athletes and coaches need to rehearse both the seven- and eight-step approach patterns and observe which one allows for the highest velocity and optimal takeoff at hurdle 1.

Women generally utilize an eight-step approach, with a very limited group of elite female athletes working to successfully manage seven steps. These patterns within the female population may vary, with shorter or less-proficient athletes taking nine steps. A premium must be put on a rhythm pattern that allows the highest velocity and optimal take-off distance from the hurdle regardless of the number of steps an athlete uses.

A premium must be put on a rhythm pattern that allows the highest velocity and optimal take-off distance from the hurdle regardless of the number of steps an athlete uses, says @ChrisParno. Share on XThe concept of rhythm within the short hurdle races was brought to my attention by Marc Mangiacotti of Harvard Track and Field. He presented charts mapping out per step distances to the first hurdle takeoff. These numbers created a visual roadmap for the athletes and coaches to manage throughout the start.

Generally, by the fourth step of an eight-step pattern, both male and female athletes will be somewhere between 4.52 and 4.71 meters from the start line. If the athlete can reach these four-step checkmarks, the likelihood of proper takeoff (distance) into the hurdle increases. These charts gave me an understanding that the hurdle start is not just mindless pushing (although that may work for some), but similar to a jumper’s approach with the goal of hitting a predetermined mark.

Races can be won and lost at the first hurdle; the foundation of a successful hurdle race is an explosive but calculated start that allows for proper positions for an aggressive takeoff.

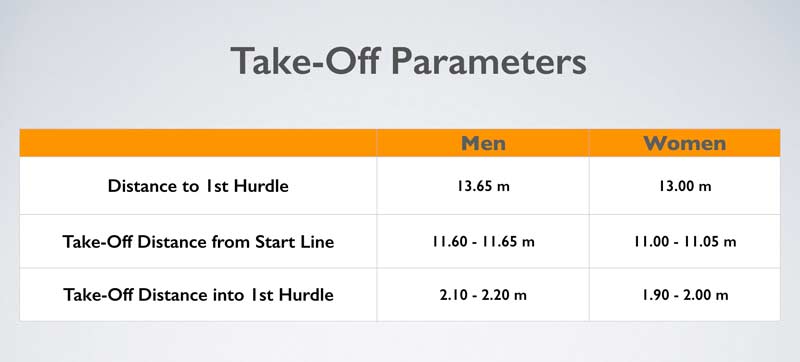

Proper Take-Off Distance from the First Hurdle

During hurdle races, the correct TO distance will allow for successful hurdle clearance and lay the foundation for all further rhythms and hurdle clearances. Not reaching the proper take-off mark may cause stuttering at the first hurdle, jumping airborne to clear the hurdle, lead leg mix-ups, etc. These athletes likely will not recover and will rarely be in the race after these anomalies occur. The first hurdle TO is as important as the takeoff in horizontal jumps, a strong plant in pole vault, and proper release in throwing events. The chance of a successful performance in any of these events without adequate completion of sequenced technical components is small.

The first hurdle takeoff is as important as the takeoff in horizontal jumps, a strong plant in pole vault, and proper release in throwing events, says @ChrisParno. Share on XGrounding the last step slightly in front of the center of mass (COM) at TO allows for stabilization. This stabilization allows for hip displacement as the COM (hips) passes over the grounded step toward the hurdle. Accurate displacements allow for the desired parabolic curve of the COM and the best chance to spend as little time airborne as possible. If this step casts out in front of COM, vertical forces will take the athlete off the ground at too high of an angle/parabolic curve. If this step is directly underneath (or slightly in front of) the COM, the likelihood of hurdle contact or low projection angles increases.

The first 6-7 steps are tied directly to the success of the last step taking off into the hurdle. A coach must often observe how the athletes manage these steps and if these athletes attain proper TO position (bandwidth for individuality). Conversely, great reaction to the gun, powerful block clearance, and/or ferocity of the first 3-4 steps won’t matter if they botch the TO (i.e., reaching, excessive vertical force, etc.).

Specific drills allow athletes to rehearse desired TO positions. Once they learn and stabilize these TO movements, the TO at higher velocities should be more consistently correct.

Displacement at Takeoff

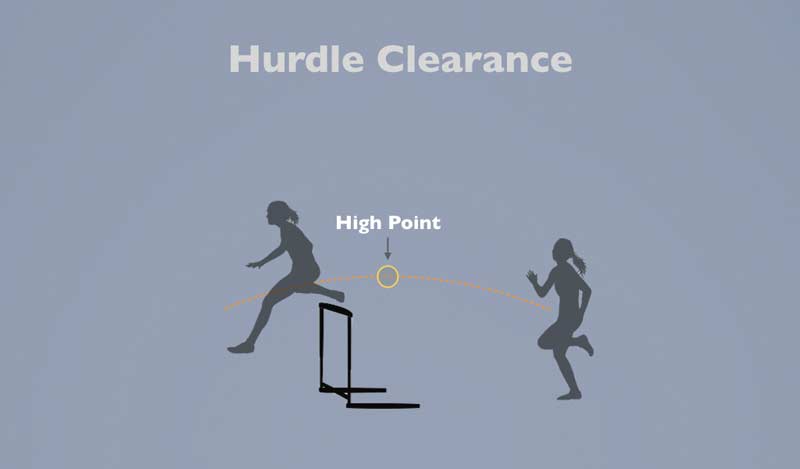

When the TO step is grounded, the hips will move past the foot toward the hurdles, and the athlete with “feel the foot behind them.” Based on the height of the hurdle (dependent on gender and TL), the hips will create a parabolic curve over the hurdle. Vertical force at takeoff will cause a high parabolic curve; conversely, a low parabola at takeoff could be a byproduct of too much horizontal force or taking off behind the desired TO mark. Proper TO positioning and hip displacement will set up an optimal parabola.

Any time the athlete leaves the ground, there will be some type of displacement in the hip, setting up a subsequent parabolic path back down to the ground. We look for the displaced parabola to hit the apex just before the top of the hurdle (displayed below), allowing the athlete to get back to the ground as fast as possible (barring outside technical influence).

Along with proper parabolic creation, proper displacement allows the muscles within the hip flexors and groin to stretch, resulting in a stretch reflex that helps the athlete actively pull the trail leg through after toe-off.

Active Technique over the Hurdle

Humans can’t get faster in the air (without outside influence). If hurdlers take the same (or similar) number of steps over the duration of the race, then logic will point to maneuvering these steps the quickest to get the best results. If hurdlers take off, displace the hips, then hold the hurdle position (trail leg straight out to the side) until making contact back to the track, they will most likely overshoot their touchdown (TD) and delay the reacceleration into the next hurdle.

At toe-off, hurdlers should be cued to actively pull (snap) their lead leg down once the ankle has cleared the hurdle and use the stretch reflex in the hip flexors to accelerate the trail leg up and through. This active movement coupled with proper timing/sequencing will allow for a quick and efficient clearance. Coaches should cue “active hurdling” or “active trail” to prevent stalling or hanging in the air. This active understanding is also tied to correct sequencing of previous acceleration patterns, proper TO, and displacement.

Coaches can break the drill into partial hurdle movements. During these “half hurdling” drills, a premium will be put on active movement of individual limbs through snapping hurdle movements.

Body Position and Front-Side Mechanics

All previous must-have movements lead into upright positions between hurdles and front-side mechanics. Hips that sink into TO will likely cause sunken hips at TD off the hurdle. The resulting sunken position will lower the hips (COM) and force the athlete to “over push” and use backside accelerative mechanics to get to the next hurdle.

Conversely, seamless TO with tall hips, correct displacement, and active clearance will allow the athlete to manage the distance between the hurdles upright while attacking with front-side mechanics. This is especially true in above-average and elite men, for whom there is a need to manage (shorten) three high-velocity strides between 9.14 meters (including take-off and touchdown distance).

Adding Meaning to Drills

The must-haves will provide structure and meaning to all “drills” selected. Coaches need to understand the parameters and elements that bring about success within the hurdle events and ensure selected drills continually develop these proficiencies. There will always be blanket warm-up-style drills that prepare the athlete for practice, but as coaches learn deficiencies within their athletes, specific drills will allow for rehearsal and an environment of learning to better future movement.

Coaches need to understand the parameters and elements that bring about success within the hurdle events and ensure selected drills continually develop these proficiencies, says @ChrisParno. Share on XThe bandwidth of drills can stretch from something as rudimentary as a lead leg wall drill to understand the attack sequence to more-advanced three-step drills at reduced spacing to quicken inter-hurdle turnover. The following five drills encompass the ideals of the five must-haves. I break each one of these drills into a beginner and advanced subcategory to help provide clarity on the depth of each drill depending on ability level.

1. Guided Trail Slides

All large lower-body movements within hurdling work proximal to distal, meaning the movements originate in the hip and work down toward the foot. The path of the trail leg (initiated directly after toe-off) starts when external rotation and flexion of the hip joint begin. This movement assists the knee up toward the elbow of the lead arm as the athlete maneuvers the hurdle. Keeping this relationship in mind, the knee stays higher than the ankle to allow the entire trail leg to come up and through before attacking back to the ground.

If the ankle is higher than the knee during hurdle clearance, there will be an outward “whiplash” motion in the trail leg, causing other rotations and imbalance while maneuvering the hurdle. Poor hip displacement at takeoff resulting in a vertical “jumping” hurdle motion, impatience in allowing the ankle to fully clear the hurdle before finishing the movement, and the athlete not fully understanding the feeling of the correct positions are all potential causes of this improper trail leg sequence.

Beginners: The goal of this drill is to slide the inside of the ankle along the hurdle plank to feel external rotation of the hip (after toe-off). The athlete will also feel the path of the knee as the hip joint flexes, bringing the knee to the elbow of the lead arm. If done correctly, the knee stays above the ankle the entire movement. Beginning athletes can slide the ankle back and forth on both sides as they learn coordination of the hurdle movement.

Advanced: This drill is more beginner in nature, but advanced athletes can place the trail hurdle further back and do quick slide-throughs, bringing the trail leg all the way through and back down to the track. The athlete will then reset, slide through, and attack the ground again. You can utilize this in the beginning of a hurdle warm-up as the advanced hurdler progresses into later drills.

Video 1. Guided trail slides.

2. Wall Attacks

Wall attacks are a stationary drill for athletes to feel hip displacement at takeoff in a controlled environment. As discussed, hip displacement sets up proper parabolic paths over the hurdles and, once slowed down in a controlled environment, can be practiced multiple times in succession.

Beginner: Athlete uses a 1- to 2-step approach as they initiate body lean toward the wall. The COM passes over the grounded take-off foot, and the hips begin to move forward. As the hands of the athlete contact the padded wall or post, the lead leg knee is parallel to the ground as if the athlete were attacking a hurdle.

Advanced: Athlete begins with take-off foot (right foot of this example) staggered in front, 10-12 feet back from the wall. As the athlete proceeds toward the wall, they step down the left (to mimic the lead leg coming off the hurdle) and then step R-L-R, with the last right being the takeoff into the wall attack. This version is more specific to the hurdle rhythm and can gradually increase speed over time.

Video 2. Wall attack drills.

3. Trail Chase

At takeoff, hurdlers initiate a stretch reflex within the hip flexor/groin as their hips are displaced. This elastic energy within the muscle assists the leg as it initiates the trail leg pull-through. Hurdlers should actively work to pull the trail leg through after takeoff. Without this active pull-through of the trail leg, the motion will be delayed and could cause future issues coming off the hurdle and will also increase time spent in the air.

Conversely, pulling through too quickly will disrupt the sequenced rhythm of the hurdle clearance. These movements must be rehearsed in a drill environment to increase the likelihood of success when velocity is added.

Beginner: Starting with the hurdle at 28 inches or lower, the athlete sets up by stepping their lead leg over the hurdle and hanging it with 90-degree angles in both the hip and the knee. Once balanced, the athlete jumps off the grounded leg and cycles that leg (trail leg) around the hurdle. The landing will be nearly synchronized, with both feet stepping back down to the ground after hurdle clearance.

Advanced: This drill will morph into what is called the “drop and pop” drill. The athlete starts on a 6- to 12-inch box and steps off directly into the last two steps before the hurdle (cut step/take-off step). Limbs are kept tight and quick as the athlete hurdles and lands, similar to the synchronized landing in the beginner example.

Video 3. Trail chase.

In both versions of the drill, you can use lower hurdle heights and even scissor hurdles, as the intent is to work a quick trail leg cycle.

4. One-Step Drill

The one-step drill addresses both the take-off and touchdown rhythms, the coordinative needs within hurdle technique, and the relationship of varying forces (both horizontal and vertical) based on spacing. This drill tends to be for a more advanced hurdler, but you can make modifications to allow any hurdler to gain proficiencies. You can split this drill into “half hurdle” leads and trails to adjust to the one-step rhythm, and the spacing can stretch anywhere from 5-10 steps from the front of one hurdle to the back of the next hurdle.

Beginner: The rhythmic pattern is the main emphasis of the one-step drill, but coaches can ease the difficulty of the drill by lowering heights and discounting spacing. The TO and TD rhythm (ba-dum, ba-dum, both in and off hurdle) is the goal, with the addition of efficient and tight hurdle technique. With this in mind, athletes can start with wicket or scissor hurdles to take out the height component and focus solely on the rhythmic pattern. Athletes should aim for an optimal airtime to effectively clear the hurdle but not spend excess time in the air. Starting with lowered heights (discounted spacing) begins to engrain the pattern that hurdlers seek to achieve both on and off the hurdle.

Advanced: The spacing and the height of the hurdles dictate how advanced this drill can become. It’s important to diagnose issues that your hurdler needs to address in both their technique and race model. Early in the fall general prep, 5-7 steps (from front of hurdle to back of next hurdle) allows for a comfortable distance for athletes to TO, land, and push to the next TO. The horizontal velocity needed to effectively execute this drill at 5- to 7-step spacing isn’t extensive, so the focus can be on the technical model.

Advancing with 7- to 10-step spacing (front of the hurdle to the back of the next hurdle), will require more horizontal velocity and force the athlete to displace the hips at a higher amplitude into the next hurdle. After athletes initially understand the rhythm of the drill at closer spacing, you can stretch the hurdles to a longer spacing. This way they will need to bring more intent to the drill to accomplish the same efficient and tight hurdle positions throughout. You can raise the height of the hurdle as athletes gain proficiency, but the height should never detract from proper hurdle mechanics.

Video 4. One-Step drill.

5. Three-Step Drill

The three-step drill emphasizes the TO and TD requirements of the one-step drill and incorporates the inner hurdle three-step rhythm. Spacing, height, and velocity dictate how advanced this drill will become, based on the needs of the individual hurdler. The general setup will have hurdles distanced from 12-28 steps (a wider range based on the needs of the hurdlers), and the athlete can split this into “half hurdling” that can isolate one side of the hurdle motion. Repeated takeoffs as well as the three-step inner hurdle rhythm will provide the athlete with many reps to lock in the rhythm of the hurdle race while focusing on the technical hurdle model.

Beginner: Similar to the one-step pattern, closer spacing and lowered hurdle heights allow beginners to start understanding and improving the efficiency of their inner hurdle rhythm. These discounted distances and heights allow the athlete to focus solely on the rhythm and clearance of the hurdles and not fear potential contact with the hurdles. Twelve to 15-step spacing (from the front of one hurdle to the back of the next) and lowered hurdle heights (12-24 inches), paired with the overall lowered velocities of the compressed spacing, allow a beginner hurdler to work on technical proficiency.

Advanced: As horizontal velocity is increased and the spacing of hurdles is extended closer to the actual race distance, the hurdler’s level of proficiency needs to increase. An upright body position and front-side mechanics are a necessity, especially at higher velocities, as the max stride lengths of hurdlers are shorter than the top-end stride lengths of a sprinter. This means the hurdler must “shuffle” or “dribble” to manage the inner hurdle SL patterns at high intensities/speeds. Advanced hurdlers can use 18- to 25-step spacing, which requires higher horizontal velocity. These higher velocities allow for rehearsal of the “shuffle/dribble” front-side bias that all advanced hurdlers will possess.

Video 5. Three-Step drill.

A Helpful Ingredient for Success

Any coach worth their salt, whether they identify as no-drill or driller, will diagnose issues within their athletes and utilize movement patterns that allow for repeated rehearsal of the desired movement. In any event or sport, the movements that most mimic the actual event will almost always be the best way to improve. Hurdlers should hurdle and sprinters should sprint, but at times these movements will need to be broken down with the goal of gaining proficiency.

If a hurdler has an issue with casting out and braking at takeoff, instead of mindlessly hurdling over and over, cueing to cut the last step, a better solution may be allowing rehearsal in a controlled environment with a movement pattern that addresses the diagnosed issue. This will, at worst, allow a reference point for the athlete to bring to the full-movement pattern of the event.

The word “drill” falls under a large umbrella of intent and purpose. Purpose-driven coaches will become great at diagnosing issues and assigning subsequent drill sequences, says @ChrisParno. Share on XThe word “drill” falls under a large umbrella of intent and purpose. Purpose-driven coaches will become great at diagnosing issues and assigning subsequent drill sequences. Drills won’t replace the importance of the full hurdle motion, but think of them as ingredients to a PR hurdle race.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Mangiacotti, M. (2014). “Rhythmic Hurdling: The Search for the Holy Grail.”

Lindeman, R. (2015). “100 / 110m HURDLE TRAINING with respect to the Contemporary Technical Model.”

Wonderful.

Loved the drills! Thank you this is really helpful

Obsessed! I love the dissection and the examples! Thank you for a great article!