At the bottom of the ocean, 12,500 feet down off the southeast coast of Newfoundland, lies what remains of the Titanic. In 1912, the deepest an underwater diver could go without catastrophic disaster—aka death—was 60 feet. At that time, experts claimed a human would NEVER be able to go deeper than 400 feet, even in a submarine, due to the immense pressures of the dark ocean. In 1986, however, Robert Ballard operated the first expedition down to the once-lost Titanic.

Since then, divers have taken scuba gear as deep as 1,090 feet and survived to tell the tale. The trick to them getting out of these depths is how well these professionals manage their approach in and out of the water. A first-time snorkeler would be a fool to think they can immediately try a deep dive without proper acclimation and training. Due to the bends (a decompression sickness), the deepest scuba dive took only 15 minutes to reach the bottom but 13 careful hours to return to the top. Unfortunately, implosion and disaster can occur when details are missed, as with the Titan submersible.

As strength coaches, we find ourselves in a different “depth” debacle.

The History of Motion (Not in the Ocean)

Do you remember the early 2000s, when squatting below parallel was a cardinal sin? Physical therapists and your local high school football coach had one thing in common—they believed deep squats were bad for your knees. After a 2003 study showed that deep dorsiflexed squats put larger stress on the knee, weight rooms across America saw a transformation.1

An unintended consequence of limited ROM squats was that coaches could slap even more weight on the bar. Instead of a safer weight room, you’d find dozens of teenagers quarter-squatting with their lives on the line and “mysterious” knee pain to follow. But if you look at many college and professional weight rooms today, you’ll see slant boards and nothing but bottomed-out squats—so, what happened?

Researchers re-evaluated the data and made an unfortunate discovery. Our limited range of motion in the weight room did not positively impact the overall health of the knee on the field. For example, rates of ACL tears went from 8.1 out of 1,000 players in 1995 to 11.1 out of 1,000 players in 2012.2,3

Was something we were doing in the weight room not transferring to the field? As injury rates continued to climb, the infamous study on dorsiflexed squats being bad was challenged, and we found ourselves trying to squat deep again. Eventually, powerlifting depth became the standard, and a lot of ego lifters started hearing “not low enough” from their coaches. Big weights were still moved, but there was a standard that had to be met for a lift to “count.”

However, like all things, this also had its flaws. There were many coaches who believed that “deep” wasn’t “deep enough.” Thus, we entered the EXTREME depth era. Hitting these extreme depths could only be possible by acclimating to the dangers of deeper waters. As squat maxes in the 2010s looked more like bench press maxes in the 1990s, coaches found themselves lacking the “intensity” that came from big weights and camaraderie.

And yet, after 30 years of the squat evolution, we still debate how athletes should perform the double knee bend. Like political parties, we have professionals squaring off on social media platforms and swearing their allegiance to the “one true way” to train while demonizing the other party. But the point of growing the body of research and learning better ways to train was never to adopt dogma and tribalism but rather incorporate everything that did work into a more ideal, holistic training system. The question is not what range of motion (ROM) to train athletes in, but rather, how we should train in ALL OF THESE ranges of motion.

The question is not what range of motion (ROM) to train athletes in, but rather, how we should train in ALL OF THESE ranges of motion, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XMany coaches already dabble in many different depths and positions, but for the rest of this article, I want to express how OUR PROGRAM uses the entire ROM to create better and healthier athletes.

1. The Elastic/Power ROM

(Initial quarter of a movement—higher speed and mostly fascial movements)

The next time you watch a sporting event, I want you to look at the depth of each athlete’s movement in a typical play. No matter the event, you will find that the majority of time is spent at the top half of all ranges of motion. This includes explosive jumps, top-speed sprints, football tackles, soccer kicks, swinging a bat, and so much more. These positions encourage a more fascial-dominant movement style, which can be performed at higher speeds with less ground contact time. Pop Warner and tee-ball coaches refer to this range as the “ready position,” but for today’s purpose, we will refer to it as the Elastic ROM.

Many Broccoli Bros at the local gym will load a squat or bench as heavy as possible and then perform a “quarter” rep…and while many coaches demonize this behavior, is it really so bad? It depends on the desired goal. Just like a snorkel can serve a purpose in diving pursuits, so can a partial range of motion exercise. When it comes to the top of a partial range of motion, here are three examples of what I do to manage these components in my programming:

- Speed of movement – A greater rate of force development can be achieved in a more mechanically advantageous position. Because of this, more speed-intended concentric movements like loaded jumps or dynamic trap bar deadlifts should be performed in this ROM.

- Potentiating movements – Pairing like ROM movements with their athletic counterparts (for example, loaded jumps with sprints and isometrics with jumps) is a great way to improve performance without exacerbating fatigue. With adequate rest in between, hang power cleans are a great tool to potentiate jumps.

- Game-specific rapid eccentrics – Although slow eccentric movements are a growing trend among social media coaches, rapid eccentric training is a great way to improve sports performance in athletes.4 These can be loaded movements, like a dynamic speed squat, or unloaded plyometrics, like hurdle hops.

Training power-specific qualities requires a more detailed program since velocity is one of the first qualities to fatigue in a training session. The Power ROM is most effectively developed at the beginning of a session, with less total volume than some other components. Depending on the athlete’s work capacity, you can perform up to 10 reps in a set at this ROM at high speeds, or you can break it up over a few sets. Using the reference that most athletes peak at 30–45 effort jumps in a game, we should consider keeping the total reps in this range to encourage higher outputs. Accumulating too many bad reps due to fatigue could negate some of the positive training effects we are looking for.5

Another way to reduce fatigue and keep velocity high is by using equipment that naturally decreases the movement an athlete can go through—for example, high handles on a trap bar or resting a bar on the pins during a bench press. This is also a great time to quantify power by using devices that measure speed or watts produced. A lower-cost method to add speed and intent is by timing sets or racing reps between athletes—timing a set of five trap bar speed deadlifts or barbell sprinter squat jumps can increase the effort from athletes.

We can also pair overcoming isometric movements with like-skilled athletic movements to maximize plyometric training at the beginning of a session. Getting an athlete to a tetanic contraction during an isometric takes time, but it’s a great way to freely quantify effort. Unfortunately, fatigue is still the enemy, forcing our overcoming isometrics to be done for five seconds at most.

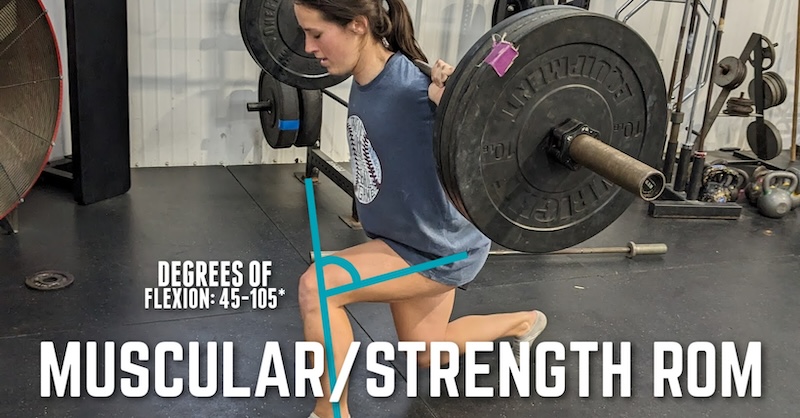

2. The Muscular/Strength ROM

(Muscular-dominant movements in sports)

Another layman’s term for this ROM would be “powerlifting range,” but it can apply to some of the full Olympic lifts and your typical hypertrophy-focused exercises. This range does a great job at hitting multiple training needs, as it allows for substantial load, can be done relatively explosively, and can introduce a lot of fatigue to an athlete.

For starters, let’s talk about putting some size on your thighs. There are many theories on how to maximally stimulate hypertrophy and neurological stimulation; a formula that some use is:

-

(weight lifted/intensity) x (reps x sets) x (range of motion)

The Strength ROM is a much greater range than the Power ROM, but it is not so extreme that it cannot be loaded maximally and done for several reps in a row relatively quickly. When you think of a squat (back/front/overhead), this ROM is below parallel (hip crease below top of knee) but not so deep that we lose the amortization phase of movement (isometric point between eccentric and concentric).

Like an exploratory submersible, athletes can spend a lot of time at this depth without running out of energy, allowing them to put in a lot of training volume. In current strength and conditioning, this is the most common ROM used, and if you post a video without hitting “depth,” the powerlift bros will let you know about it. Ideally, this ROM is used for:

- Ideal strength development ROM – Anecdotally, millions of powerlifters worldwide have shown that significant load can be lifted in this range. Likewise, we periodically see high-level athletes enter this ROM as they perform high-power movements during their sport. Typically, these higher-force movements include larger ground contact times and slower eccentric loading than the aforementioned fascial range. Athletes with concentric-dominant tendencies will do better in this ROM than their more eccentric counterparts. This ROM also greatly develops the amortization phase because the braking occurs in a less mechanically advantageous position (more muscular loading than ligament). This is why traditional power lifts like bench presses, squats, and deadlifts are great. Because we still see a large amount of high-force performance in this ROM, we want to train it effectively with relative load.

- Optimal hypertrophy stimulating ROM – Since putting on functional size is an important part of many sports—but introducing too much fatigue can result in impaired sports play—we want to spend the least amount of time necessary to encourage muscle protein synthesis. This ROM combines the degrees of movement and possible load lifted to encourage a greater mechanical stimulus for “growth.”

Fatigue is a crucial component to consider when building a training program. If we burn too much energy at the wrong time, we will inhibit the quality of work we can do throughout a session. Training the strength ROM is best done toward the middle or end of a session where speed is no longer the focus, but we have not over-exerted athletes beyond their ability to move heavier weights.

This looks like your more traditional strength training exercises, such as back squats, deadlifts from the bar or hex handles, or barbell or DB bench presses to the shirt. This can also include more power-specific drills like kneeling or half-kneeling medball throws. The overall volume needs to be dictated by the athlete’s max recoverable volume, but the sets will have reps of 1–10 with only a few working sets per day per exercise.

As much as some in the S&C community want to abandon the idea of lifting heavier loads in favor of higher speeds or alternative styles of training, there are arguments to keep bending bars and getting PRs. Neurological adaptations to heavier weights seem to be unique and valuable, and we should still include them in sports training, thus why I have called this the “Strength” ROM.6

As much as some in the S&C community want to abandon the idea of lifting heavier loads in favor of higher speeds or alternative training styles, there are arguments to keep bending bars & getting PRs. Share on X3. The Tissue Capacity ROM

(The extreme range of motion a tissue can currently support)

I would call this the “modern” ROM, but there have been guys like Charles Poliquin preaching the importance of this for years. This ROM laughs at the coaches and PTs from yore who claimed performing deeper squats would implode your knee like a mismanaged submarine on the ocean floor. Without proper acclimation and a great plan, these depths can mean disaster for the unwitting. Range of motion goes beyond “traditional” depths and focuses on the individual’s max capacity of a joint and its surrounding tissues. We can also call this the End Range of Motion (EROM), but most individuals will have a current capacity they are limited to and a true capacity they can work toward.

This end ROM is much harder to achieve any substantial load in and lacks the speed potential of other ROMS, but it plays a crucial role in preparing soft tissue for the EXTREMES of sports and life. Share on XAlthough this EROM is much harder to achieve any substantial load in and lacks the speed potential of other ROMS, it plays a crucial role in preparing soft tissue for the EXTREMES of what might happen in sports and life. When an athlete experiences tendonitis or even tears/trauma to connective tissue, it is always because the demands of the moment supersede the preparedness of the structure. Ideally, we would use this EROM for:

- Improving connective tissues’ durability – Large ranges of motion put greater stretch and load on connective tissues like tendons and ligaments. Many athletes struggle with bouts of tendonitis, and “prehab” should be considered for hotspot areas within specific sports. Large ROM training should be included as a holistic approach to improving the health of athletes.

- Enhancing proprioception at extreme ranges of motion – If you’ve never managed this challenging range, you won’t move efficiently in it. Like transitioning from a snorkel to a scuba tank, more details have to be managed in order to come out unscathed. We want athletes to have cognitively been in this range (even if at lower speeds and loads) to help them manage that situation better.

- Increasing overall “flexibility” – We are learning that flexibility is a very neurological response. An athlete’s nervous system will inhibit them from entering a space if it is deemed “unsafe.” By using load and frequency, we can encourage our nervous system to trust a range of motion without just putting the brakes on. Although our bodies are just trying to protect us, something as simple as reduced ankle dorsiflexion can increase the risk of an ACL tear.7

It wasn’t that long ago that doctors couldn’t confirm the ability of ligaments like the ACL to thicken/hypertrophy due to training. Traditional, partial ROM lower-load training did not seem to cause a positive change that could be recognized with any confidence. However, when researchers looked at athletes whose sport demanded maximum EROM-loaded movements, they were able to see significant ligament thickening.8

It would seem that the greater the ROM and stress placed on connective tissue is, the greater the adaptation and, thus, resilience. Large ROM movements can affect not only the structure but also the stability of the limbs they are associated with. Many cruciate ligaments have morphologically different sensory nerve endings, turning them into a large contributor to proprioception.9

This training range is unique because its application varies depending on the individual or training goal. It can be done at the beginning of a session with lighter loads and longer times under tension—almost as a warm-up—or at the end as a capstone to a tough session with more weight, faster speeds, or higher volumes. Just like an athlete’s ability to generate speed or power in the first ROM or the amount of weight they can lift in the strength ROM, the abilities of athletes to move in this ROM greatly vary. Because of this, it is important to mediate load, understand it’s more fatiguing for some than others, and possibly use devices like slant boards or assisted straps for larger movements at specific joints.

As with all movements, we want to stay within an athlete’s current capacity and expand that over time, but since this has the most degrees of movement, it is more likely to cause a problem if your athletes are moving “poorly.” A great way to teach movement quality in this space with VERY LOW risk or irritation is with yielding isometrics. By performing longer-duration active holds (30 seconds or greater), not only will athletes build confidence, but their connective tissues will also get a greater response to the stress.

If absolute strength in this ROM is the goal, performing submaximal and higher-rep movements at the end of the session can also be done. By finishing a session with controlled sets of 10 or working sets that last longer than 30 seconds, athletes can “restore” some movement qualities that might have been inhibited by faster or harder training. For many older athletes who have not engaged in this type of training from an earlier age, you will need to lower their movement expectations at first or provide them with assisted devices to create flexion in some of the joints.

Working at Depth

Not every coach is trying to discover treasure in the Titanic, but that doesn’t mean our athletes shouldn’t be prepared for the extremes that each depth can bring in sports. There isn’t always time or energy in every training session to develop each position properly, but any coach can program to include all of these ROMS over the course of a week with all of their athletes.

You wouldn’t send a scuba diver to the Mariana Trench in a 1912 suit, and you probably shouldn’t send someone to the pitch, field, or court without the proper preparation, either.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Fry AC, Smith JC, and Schilling BK. “Effect of knee position on hip and knee torques during the barbell squat.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2003 Nov;17(4):629–33. doi: 10.1519/15334287(2003)017<0629:eokpoh>2.0.co;2. PMID: 14636100.

2. Powell JW and Barber-Foss KD. “Injury patterns in Selected High School Sports: A Review of the 1995–1997 Seasons.” Journal of Athletic Training. 1999;34(3):277–284.

3. Joseph AM, Collins CL, Henke NM, Yard EE, Fields SK, and Comstock RD. “A multisport epidemiologic comparison of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in high school athletics.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2013;48(6):810–817.

4. Hernandez JL, Sabido R, and Blazevich AJ. “High-speed stretch-shortening cycle exercises as a strategy to provide eccentric overload during resistance training.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2021;31(12):2211–2220.

5. Ben Abdelkrim N, El Fazaa S, and El Ati J. “Time-motion analysis and physiological data of elite under-19-year-old basketball players during competition.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007 Feb;41(2):69–75; discussion 75. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.032318. Epub 2006 Nov 30. PMID: 17138630; PMCID: PMC2658931.

6. Jenkins NDM, Miramonti AA, Hill EC, et al. “Greater Neural Adaptations following High- vs. Low-Load Resistance Training.” Frontiers in Physiology. 2017:8.

7. Fong CM, Blackburn JT, Norcross MF, McGrath M, and Padua DA. “Ankle-dorsiflexion range of motion and landing biomechanics.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2011 Jan-Feb;46(1):5–10. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.1.5. PMID: 21214345; PMCID: PMC3017488.

8. Grzelak P, Podgorski M, Stefanczyk L, Krochmalski M, and Domzalski M. “Hypertrophied cruciate ligament in high performance weightlifters observed in magnetic resonance imaging.” International Orthopaedics. 2012 Aug;36(8):1715–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1528-3. Epub 2012 Mar 25. PMID: 22447073; PMCID: PMC3535026.

9. Johansson H, Sjölander P, and Sojka P. “A sensory role for the cruciate ligaments.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1991 Jul;(268):161–178. PMID: 2060205.