Like many other health professionals, as well as lay people, I used to believe that pain only comes from an injury or is caused by locked joints, joint misalignment, weak or tight muscles, ruptured disks, poor posture, and degenerative changes.

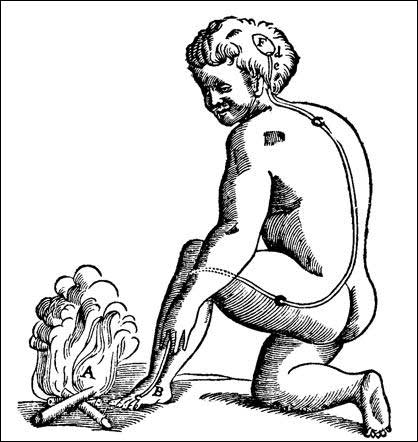

Many people also believe that pain means something is wrong in their body, in the location where they have the pain. This belief is based on what is popularly called the “Cartesian” model of pain, put forward by the philosopher Descartes nearly 350 years ago. Descartes wrote in his book, Treatise of Man: “The flame particle jumps from the fire, touches the toe, moves up the spinal cord until a little bell goes off in the brain and says, ‘Ouch. It hurt.”

This is closely related to what we learn throughout our childhood; namely, that pain always has a clear cause. We bump our toe, and the result is a painful toe. We fall and hurt our knee, and we get pain in our knee. This is a natural response, and it’s a good thing too, because it causes us to protect the injured area and try to avoid hurting it more. It causes us to act, and it promotes healing through rest (1).

This leads people to draw the conclusion that, if they have pain, it is because they have tissue damage in their muscles, tendons, or joints. Unfortunately, this conclusion is sometimes wrong, especially when pain lasts longer than the normal healing time. Both pain and neuroscience research show us that, when you have pain, it has less to do with the actual state of your tissue, and more to do with your brain and nervous system (2).

Pain has more to do with your brain and nervous system than with your muscles, tendons, and joints. Share on XQuite frankly, pain is not as simple as most people, and even some health professionals, think. Pain is a multifaceted experience that is produced by multiple influences and factors (1). Pain is not simply a sensation caused by an injury, inflammation in the body, or tissue pathology (1).

Injuries often hurt because they activate specific receptors in the body called nociceptors. Nociceptors are specialized neurons that alert us to potentially damaging stimuli; they detect extremes in temperature, pressure, and compounds produced by an injury. A non-technical name for them is danger receptors.

Recent research has shown us that you actually can have pain in the body without anything being wrong in the area of that pain. You can also have “damage” and so called degenerative changes in the body without any pain.

As I see it, there are four possibilities:

- Having tissue damage and pain

- Having no tissue damage and no pain

- Having pain but no tissue damage

- Having tissue damage but no pain

The first two possibilities are the ones that almost everyone takes for granted, while the last two possibilities are often forgotten. However, these last two are very important to keep in mind. If you have pain for three to six months, it is usually classified as chronic pain. This type of pain often has more to do with your brain and nervous system than with the actual condition of the tissue.

In this article, we will look into the last possibility—having tissue damage without pain. There are many people who walk around with knee, back, or shoulder pain that drastically limits their ability to be active or live a normal life. Interestingly, there are also many people who have some significant “damage” in their body, also known as degenerative changes, but without any symptoms or pain.

Some examples from research include:

- Researchers looking at the MRIs of participants’ lumbar spine area found that 80% of the participants without any symptoms or pain could be diagnosed with one mild disc protrusion or a disc herniation in the lumbar spine, and 38% of participants had two or more of these degenerative changes (3).

- MRIs taken of the shoulders of participants who had neither symptoms nor pain showed that 34% of them had rotator cuff tears. This increased to 54% when researchers only looked at people above 60 years old (4).

- Researchers found that 37% of patients in an emergency clinic (that were alert, rational, and coherent) did not feel pain at the time of their injury. Most of these patients reported pain within an hour of injury, but some patients reported delays of as long as nine hours or even more. In patients with lacerations, cuts, abrasions, and burns, 53% had a period of time without pain and, even in the group of patients with fractures, sprains, bruises, amputation of a finger, stab wounds, and crushes, 28% went through a period without pain (5).

- Of a group of participants in another study, 20% to 57% had different types of degenerative changes, like disc herniation or spinal stenosis, varying by age. The incidence was also shown to increase with age (6).

- In a study of people with clinical symptoms of knee osteoarthritis, 76% were found to have meniscal tears without any symptoms or pain (7).

- In a new systematic review of spinal degradation, the researchers determined that degenerative changes could be viewed as a normal part of aging, and that they are common in individuals without pain (8).

- When the shoulders of subjects in one study were imaged by ultrasound, researchers found “abnormalities” in 96% of them; again without any symptoms or pain (9).

- In an editorial published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, a professor of sport medicine stated that degenerative meniscus tears (in the knee) should be looked upon as “wrinkles with age” (10).

- A cross-sectional study of MRIs done on the cervical spines of 1,211 participants ages 20-70 found that 87.6% of them had a bulging disc. For participants in their 20s, 73.3% of the males and 78.0% of the females had bulging discs; again without any pain (11).

If we look closer at the data from the “Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations” (8), it shows that 60% of the people that are 40 years old have disc degeneration, 50% have a bulging disc, 33% have disc protrusions, 18% have facet degeneration, and 8% have spondylolisthesis. However, none of them have symptoms or pain.

The incidence increases dramatically when we look at data for people 80 years old. Here, the data shows that 96% have disc degeneration, 84% have a bulging disc, 43% have disc protrusions, 83% have facet degeneration, and 50% have spondylolisthesis. Still, none of this group has symptoms or pain.

All of the participants and patients in the studies I highlighted earlier—with the exception of the paper on patients in the emergency clinic (5) —had all sorts of things “wrong” in their body, but none of them felt pain.

How can that be? Why does your uncle’s shoulder hurt when his rotator cuff is torn, while people in these studies had no pain? And why do you get back pain when working in the garden, while all of these people can have degenerative changes without feeling any pain? What about the old man who has arthritis in both knees, but only the left one hurts? The answer is that pain is nowhere near as simple as we believe.

A wide range of scientific studies show the concept of pain is not as simple as we believe. Share on XWhat does modern pain research say about pain, and what can we learn from the last 30 years of research on the experience of pain? A statement made by world-leading pain researcher, Professor Lorimer Moseley, serves as a gateway to this new research. Moseley is a professor of Clinical Neurosciences and Chair in Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences at the University of South Australia, and is at the forefront of pain research. His numerous scientific studies have extensively increased our understanding of what pain is, and what it is not. Moseley said that, “pain is an unpleasant conscious experience that emerges from the brain when the sum of all the available information suggests that you need to protect a particular part of your body.”

Pain is, therefore, the sum of your environmental context (i.e., a calm or stressed environment; a battlefield, hospital, home), the degree of danger signal (nociception), your beliefs, your expectations, and your past experiences, as well as many other factors. You will experience pain only when your body perceives a large-enough threat in relation to the context (12,13). In layman’s terms, you could reconceptualize pain as the body’s alarm system, which reacts to threat, danger, and injury. The alarm (pain) is often activated when we get an injury, but the alarm system is highly intelligent and has the ability to warn us before we get an injury, thereby increasing the probability that we avoid the injury.

The legendary Danish doctor and anatomy professor, Dr. Finn Bojsen-Møller, stated: “It is fundamental to the body’s self-protection ability that pain begins before reaching the breaking point. Without the painful experience, there is no possibility of keeping the body and tissue intact and whole (14).”

This scientific research, and its implications, are both good news and bad news. The good news is that, through advances in pain science research, we have a much more complete understanding of what pain is. The bad news that emerges from this research, however, is that pain is a complex experience influenced by multiple factors. This means that there are no quick fixes to the complex problem that is pain, and this is a big challenge for the health professionals who are trying to sell quick fixes. But it also gives hope for new advances in pain treatments that integrate the complexity and multifactorial nature of pain.

References

- Melzack R, Katz J. Pain. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2013; 4(1):1-15.

- Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2007; 12(3):169-178.

- Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jul 14; 331(2):69-73X.

- Sher JS et al. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995 Jan; 77(1):10-5.

- Melzack R, Wall PD, Ty TC. Acute pain in an emergency clinic: latency of onset and descriptor patterns related to different injuries. Pain. 1982 Sep; 14(1):33-43.

- Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Mar; 72(3):403-8.

- Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, Totterman S, Gale ME, McLaughlin S, Einhorn TA, Felson DT. The clinical importance of meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Jan; 85-A(1):4-9.

- Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, Halabi S, Turner JA, Avins AL, James K, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014 Nov 27. [Epub ahead of print].

- Girish G, Lobo LG, Jacobson JA, Morag Y, Miller B, Jamadar DA. Ultrasound of the shoulder: asymptomatic findings in men. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Oct; 197(4):W713-9.

- Risberg MA. Degenerative meniscus tears should be looked upon as wrinkles with age–and should be treated accordingly. Br J Sports Med. 2014 May; 48(9):741.

- Nakashima H, Yukawa Y, Suda K, Yamagata M, Ueta T, Kato F. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of the cervical spines in 1211 asymptomatic subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015 Mar 15; 40(6):392-8.

- Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Man Ther. 2003 Aug; 8(3):130-40.

- Legrain V, Iannetti GD, Plaghki L, Mouraux A. The pain matrix reloaded: a salience detection system for the body. Prog Neurobiol. 2011 Jan; 93(1):111-24. Epub 2010 Oct 30.

- Bojsen-Møller, F. 2001. Bevægeapparatets anatomi. 12th ed., Denmark: Munksgaard.